interviews

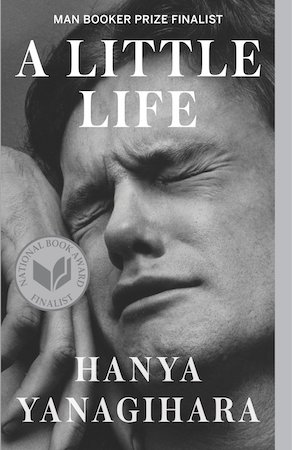

An Interview with Hanya Yanagihara

The author of "A Little Life" on a stubborn lack of redemption

Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life is an unsparing novel that follows the lives of four college friends as they achieve the successes they once dreamed of and strived for. There is a fairy tale quality to the wealth and fame these men achieve, but like all fairy tales, there is an underlying darkness.

The darkness at the center of this novel emanates from Jude St. Francis, a successful lawyer by any measure, but a man who remains an enigma to friends and family nearly to the end. The reader bears witness to the aftermath of the childhood abuse Jude St. Francis suffered, and barely survived, with the understanding that the brutality of the witnessing cannot compare to the experience itself. Unable to heal himself, or be healed by others, Jude is a character that calls into question the redemptive narrative arc we too often expect from stories of trauma. Yanagihara would argue that this isn’t a story about trauma but about life. Either way, she asks the tough questions: how do we live, and why?

Yanagihara and I corresponded through e-mail over the course of a few weeks as she traveled in Sri Lanka, Hong Kong, and Japan. We discussed trigger warnings, empathy, the limits of psychology, and suicide.

Adalena Kavanagh: A Little Life centers on the friendships of four men, and your previous novel, The People in the Trees, also mainly centered around male characters. You have said that men often have a smaller emotional vocabulary than women do (an idea a female therapist also shared with me, coincidentally). Could you speak more about that and why you have chosen to write primarily about men?

Hanya Yanagihara: My best friend — who’s a man of tremendous depth of emotional perception and intelligence — disagrees with me somewhat on this point. But I do think that men, almost uniformly, no matter their race or cultural affiliations or religion or sexuality, are equipped with a far more limited emotional toolbox. Not endemically, perhaps — but there’s no society that I know of that encourages men to put words to the sort of feelings — much less encourages their expression of those feelings — that women get to take for granted. Maybe this is changing with younger men, but I sometimes listen to my male friends talk, and can understand that what they’re trying to communicate is fear, or shame, or vulnerability — even as I find it striking that they’re not even able to name those emotions, never mind discuss their specificities; they talk in contours, but not in depth. But in order to name emotions, you have to be taught to name them. It’s like that famous study of depression in Japan: the respondents self-identified a set of symptoms that here would be the means to diagnose them with clinical depression. There, it was merely a set of symptoms. I’m not saying this is bad or good; only that when it comes to matters of the self, and self-identity, society teaches you what’s allowable to feel and communicate.

I do think that men, almost uniformly, no matter their race or cultural affiliations or religion or sexuality, are equipped with a far more limited emotional toolbox.

As a writer, it’s a great gift — and an interesting challenge — to write about a group of people who are fundamentally limited in this way (and who happen to be half the world’s population). Male friendship, by which I mean a friendship between two men, is by its very nature different in scope and breadth than one between two women, or between a woman and a man. In The People in the Trees, one could argue — as I would — that the narrator, Perina, behaves the way he does in part out of a grotesque and misshapen interpretation of loneliness. I had intended him, in many ways, as a fundamentally naive character, one who allows himself to mistake perversion for love. In A Little Life, one of the things I most enjoyed exploring is how these men’s friendships, while close by anyone’s definition, are also built upon a mutual desire to not truly know too much. Again, I’m not saying that’s a bad or good thing — one needn’t confess everything to a friend to be known by him — but I do think that a friendship between two women (once again, for better or worse) is yoked by shared confessions.

The way Jude handles his past is meant to be particularly male as well. I don’t know a single woman who hasn’t at least worried at some point in her life — if only fleetingly — that she might be in sexual danger, that she might be preyed upon. It’s something we grow up knowing, because for many women (as history and mythology have taught us), it’s a real threat. Parents worry that their boys might be killed in an accident or in some act of violence; they worry their daughters might be raped. Plenty of males are preyed upon in the same way, of course, but there remains a certain and specific shame surrounding the subject. If you’re a woman and you’re sexually assaulted, it takes away nothing of your rights to womanhood — I don’t think men feel the same way.

AK: Regarding your character you say, “one could argue — as I would — that the narrator, Perina, behaves the way he does in part out of a grotesque and misshapen interpretation of loneliness.” This strikes me as a very empathetic treatment of a character that most would find it hard to have empathy for. Why treat those characters society would deem monsters with empathy at all?

HY: Well, from a literary perspective, you have to: if you’re a writer, you must be able to summon empathy for all your characters, even and especially the despicable ones. You needn’t like them, but you must respect them — even if you don’t respect every aspect of them. If not, that character becomes simply a catalog of his pathologies, and that’s a hollow character. Actually, that’s not even a character: it’s just a pastiche of bad behavior. I tried to keep this in mind in A Little Life when I wrote the characters who make Jude’s life so awful — Caleb and Brother Luke and Dr. Traylor. They were always much more complicated people to me than they are to him; he sees them one way, of course, and so he should. But I tried to make all of them a little mysterious to the reader, to suggest that there were other lives they led, that they were someone else entirely to the other people in their life. Caleb, especially, should come across as someone with nuance, with an unseen but suggested other persona: Jude is meeting him as an adult, and so even he’s able to see that the way Caleb behaves with him might not be the way he behaves with other people: he has a sister he’s close to; he has a job where he’s clearly respected; he finds a boyfriend after Jude. This, of course, is exactly what he fears: that Caleb’s behavior towards him is indicative less of the core of Caleb’s identity, and more a set of responses that’ve been inspired by Jude himself. (Because Jude encounters Brother Luke and Dr. Traylor as a child, he’s much less able to see who else they might be besides his abusers — and so too, therefore, the reader; in Jude’s childhood sections, I tried to tilt the semi-omniscience that informs his adult chapters to something more intimately his point of view, which is by necessity narrow and childlike. But I always knew they were someone else, that they had other lives, other interests, other qualities, or I wouldn’t have been able to write them authoritatively. One hopes, as a writer, that your readers can sense as well some of what you’re not saying about your characters, that one senses the totality of their conception.)

Once we start calling people monsters, we start sacrificing our sense of curiosity, our obligation to ask how they became that way.

In life, though — that is to say, not on the page — does everyone deserve empathy? Maybe not. I certainly wouldn’t argue that everyone deserves compassion; I think it’s a privilege you can lose. But I do think that everyone is much more complex and difficult to comprehend than their actions suggest. Once we start calling people monsters, we start sacrificing our sense of curiosity, our obligation to ask how they became that way, and why they did what they did: life, and certainly fiction writing, is about being endlessly fascinated by the human condition — naming someone a monster is lazy; it allows you to stop thinking and questioning.

AK: In your first novel, The People in the Trees, one of the characters is accused of sexually abusing a boy, and in A Little Life, the main character, Jude, suffers sexual abuse as a child and teenager. What drew you to this subject, and where do you see your work fitting into a cultural climate where trigger warnings are being debated on college campuses?

HY: I suppose I’m interested in the subject first, because the act of sexually abusing a child is the ultimate abuse of power. Second, I think it ruins people. Some in big ways, others in small ways. But it means that in the long road to defining oneself as a human, one must also negotiate around an enormous and often immovable rock.

As for trigger warnings: I’d never heard of this term before (it’s been a while since I was in college)! All I can say is that I think it’s very dangerous to isolate oneself from information or art or history or news because the subject is painful. I understand the instinct. But being a curious person — which I think is the ultimate goal of being alive — means allowing yourself to be intellectually and emotionally vulnerable as much and as often as you can. I’d argue that despite its cost, it’s the subjects that makes us the most uncomfortable that we have to challenge ourselves to brave more, not less, often. As regards sexual violence, well, were we to avoid that topic, it’d mean avoiding not only much of art, but also history itself: it’d mean avoiding the world. Much as I hope the reader is there in this book to bear witness to Jude’s life and his suffering, we equally owe it as humans to witness other humans’ suffering as well, and not turn away because it makes us uncomfortable.

AK: Those in favor of trigger warnings would argue that those who have been victims of trauma have the right to opt out of an experience that would further traumatize them. What would you say to a student who wanted to exercise their right to opt out of experiencing your book, if it was assigned in a class?

HY: I’d say we never really know how we’re going to react until we start reacting. To try to preemptively shield yourself from an experience — to say, in essence, this book is about something that I fear is going to really upset me, so I’d better protect myself by not exposing myself to it at all — is not only limiting, but also means you might be preventing yourself from experiencing something else, something you thought you never would, or never have. It also reduces art to a single topic, and to a single reaction: I would hate it if this book were dismissed as a book about abuse. Abuse is part of it. But I hope it’s also about other things as well. All books are. This is an obvious point, but no one book is about one thing (unless it’s a very boring book). The point of reading, especially fiction, is not to have confirmed what you already think or feel, but to make you think anew about what you already think or feel.

AK: Having known several women who have suffered sexual abuse, Jude’s psychology of self-loathing, shame, and tendency to blame himself for the abuse he suffered struck me as one of the most accurate portrayals of the mindset of an abused person I’ve read. Did you do any research to build this character? Was it difficult to write this material?

HY: No, I didn’t do any research; Jude came to me fully formed, and writing his sections were always the easiest. He’s a very consistent character — or is meant to be — which is, arguably, part of what dooms him.

AK: The way you reveal Jude’s childhood is relentless and seems to mirror Jude’s inability to forget what happened to him, despite the immense success he achieves in his life. In this way you resist the comfortable narrative arc of abuse followed by healing. Jude resists therapy, to the frustration of his friends and family (and this reader!), and one of the main questions the book seems to address is whether talk therapy works — what do you think the limits of therapy are?

HY: One of the things I wanted to do with this book is create a character who never gets better. And, relatedly, to explore this idea that there is a level of trauma from which a person simply can’t recover. I do believe that really, we can sustain only a finite amount of suffering. That amount varies from person to person and is different, sometimes wildly so, in nature; what might destroy one person may not another. So much of this book is about Jude’s hopefulness, his attempt to heal himself, and I hope that the narrative’s momentum and suspense comes from the reader’s growing recognition — and Jude’s — that he’s too damaged to ever truly be repaired, and that there’s a single inevitable ending for him.

One of the things that makes me most suspicious about the field is its insistence that life is always the answer.

This book is, obviously, a psychological book, but not one about psychology. I didn’t use psychological language, and I didn’t want to — nor encourage the reader to — diagnose Jude in clinical terms. As for the limits of therapy: I can’t speak to them, only that therapy, like any medical treatment, is finite in its ability to save and correct. I think of psychology the way I think of religion: a school of belief or thought that offers many, many people solace and answers; an invention that defines the way we view our fellow man and how we create social infrastructure; one that has inspired some of our greatest works of art and philosophy. But I don’t believe in it — talk therapy, I should specify — myself. One of the things that makes me most suspicious about the field is its insistence that life is always the answer. Every other medical specialty devoted to the care of the seriously ill recognizes that at some point, the doctor’s job is to help the patient die; that there are points at which death is preferable to life (that doesn’t mean every doctor will help you get there, of course. But almost every doctor of the critically sick understands the patient’s right to refuse treatment, to choose death over life). But psychology, and psychiatry, insists that life is the meaning of life, so to speak; that if one can’t be repaired, one can at least find a way to stay alive, to keep growing older.

Obviously, this is reductive, and many, many people think otherwise, including my own dearest friend. He argues that therapy shouldn’t be indicted as a dishonest profession simply because therapists won’t tell patients they can kill themselves. And that the therapist’s role is to make one’s life better, at least in some measure, through self-examination. But I’m not convinced. However: maybe there is in fact a therapist or psychiatrist out there, who thinks that life is, for some people, simply too difficult to keep pursuing; who will give a suicidal patient permission, as it were, to die.

AK: I never thought of psychology in this way, but I can see your point — it is a belief system, one that won’t “work” unless you believe that it does work. There are moments in the book when characters wonder if they had only pushed a little harder, if they had just asked the right questions, they could have helped Jude with his demons. I thought you had given readers a key or clue early on in the book when Jude’s social worker encourages him to talk about his experience of abuse but he is unable to. She says that if he doesn’t talk about it at that moment he never will. I was left feeling that because he had not processed his abuse early enough, he was unable to heal, but from what you are saying, that might have been a naïve interpretation on my part. Was that conscious on your part — to give the reader false hope that something could have been done if only it had been done early enough?

HY: I do think that there are moments in our lives in which the door opens, and you can make a choice to walk through it: that you can name what’s been unnameable, or that you have someone close to you whom you can truly trust to accompany you. I was talking about this with my friend, and he said that what he found so haunting about Jude’s story is that the reader can’t help but wonder what would’ve happened if he’d been psychologically helped — or more accepting of help — earlier, if he wasn’t left to interpret his life by himself; if he had been encouraged to take other lessons from it than the ones he does. I do think that Jude’s life would’ve ended the same way no matter what. But I also think that he could have had a happier, or at least less tortured, life as well.

But I also think there’s a point in which it becomes too late to help some people: that there’s a time past which the damage has calcified so completely that there’s no undoing it.

AK: You say, “But I’m not convinced. However: maybe there is in fact a therapist or psychiatrist out there, who thinks that life is, for some people, simply too difficult to keep pursuing; who will give a suicidal patient permission, as it were, to die.”

Just to push back a bit, you could also argue that the urge to suicide is a symptom of illness, and not a rational choice someone makes. What do you think of that argument?

HY: Sure, and in the West, that’s exactly what we think: that suicidal thought is a symptom of a sick, or at least troubled mind. But I do think that that’s something of a cultural and religious construct. In America, we think there’s something shameful about it; we react to suicides with something approaching rage: What was he thinking?; It’s the coward’s way out. But in Asia, suicide isn’t viewed in the same way. Or it wasn’t, for many years. Here, we associate suicide with despair. There, you might say that the cause can be, sometimes, culturally sanctioned. This is not to say suicide isn’t just as devastating and often perplexing in the East as it is in the West — only that I don’t think there’s a single way to consider its meaning.

AK: If you’ve been following the literary conversation over the last few years you might have noticed that women who write complex texts and characters are often asked about likable and unlikable characters, in a sometimes accusatory way, as if by writing complex characters they are being willfully difficult instead of merely being thoughtful writers. I think your answer, that to call someone a monster is lazy, is a good response to that line of questioning. That said, you yourself have said that there is a fairy tale quality to A Little Life. There is also allusion to Christianity in the text, often in a sinister way, since Jude’s first abuser is a monk. What was your inspiration for this, and what texts or mythologies are you alluding to?

HY: We think of fairy tales (and fables, and folk tales: I’ll lump these three in a group, though they’re quite distinct from one another) as very simple stories, and while narratively, most of them are indeed fairly linear and straightforward, the lessons they impart about the world and how it works are often more unpredictable than we credit them. Many others have written far more brilliantly about these types of stories than I ever could, but I will just say that there is, in a significant number of these stories — across cultures, across countries — a stubborn lack of redemption. Sometimes the good child is rewarded, and the bad witch punished, but just as often, they’re not: or what must be endured by the hero or heroine is so terrible, so grotesque, that happiness, usually in the form of marriage or a reunion, seems almost meaningless, an unsatisfying answer to outlandish feats of survival.

This book adheres to many of the conventions of the classic Western fairy tale: there’s a child in distress, who’s made to face challenges on his own. The era is suggested rather than named. There are no conventional parental figures, in particular mother figures. (Like many fairy tales, I hope this book is defined as much by its absences as its presences.) And yet, unlike a fairy tale, this book concerns itself more with the characters’ emotional response to these challenges and events than the circumstances themselves; I tried to meld the psychological specificity of a naturalistic contemporary novel with the suspended-time quality of a fable. Part of fairy tales’ lasting power is attributable to the fact that they never address their characters’ inner lives (a relatively modern literary concept, that); the particulars of the plot are generally far more important than the characters themselves. With A Little Life, I tried to do the opposite.

AK: It’s interesting to me that you would contrast a non-Western idea — that suicide is sometimes culturally sanctioned, as you say — with characters so clearly rooted in Western life and culture. There has been much talk about the lack of diversity in literature, meaning most books being published in America are by white writers, about white characters. Without calling attention to it, your book has several non-white main characters, which I think could serve as a model of how to write non-white characters without having the text be about capital R race. Was this is a conscious choice on your part?

You have to ask yourself: why am I making this person someone other than who I am, and who else are they to me besides their otherness?

HY: I think the only key to writing about characters who aren’t your race — or gender, or sexual orientation, or religion, for that matter — is not letting that otherness become the character’s defining trait. Race is part, a huge part, of who a character (or person) is, but where writers (and people) get into trouble — rightly — is by making race all of who that character is, as if “black” or “Asian” or “Jewish” or “white” comes with a certain and unchangeable set of characteristics. (By the way, yes, the book has several non-white characters, but the fact that it’s only them you singled out is telling: the universal “we” or “you” in a novel isn’t a white person — or at least, it’s not to me.) I can’t stand it when I’m reading a book and in comes a character who’s gay and I know that that character is therefore going to be sassy and snappy and deliver bitchy-but-wise pieces of romantic advice (this still pops up in fiction more than you might think; sometimes as broadly as I’ve described it, other times more subtly). You have to ask yourself: why am I making this person someone other than who I am, and who else are they to me besides their otherness? If that’s the only thing you can see of them, and the only thing you have determined about them, then chances are they’re not a character: they’re a symbol of your own discomfort. And symbols are boring to read.

AK: Oh, I don’t think white is the universal we or you, either, and I try to write against that. If I name the race of one character, I name the race of the white characters as well. This might be because I’m biracial Asian but I’d hope not. That said, as you stated, writing non-white or non-straight, or characters that are often “othered” by American culture, and publishing, is often done using stereotypes. I was pointing out how well you write these characters. Does it bother you to have these things pointed out? I have been uncomfortable with the term “diverse” books (it kind of makes my skin crawl), meaning books by non-white authors, and about non-white characters, but I’m not sure how else the publishing industry, and the literary community, can consciously promote these authors (with the best intentions of being inclusive, and not marginalizing writers) without using that sort of term. Do you have any suggestions?

HY: When I was in book publishing, now almost two decades ago, publishing houses marketed books by non-white writers (or gay writers) much more aggressively to a specific audience: books by Asian American authors were sent to Asian American magazines, books by gay authors to gay magazines, etc. Those were the days of identity culture at its most blunt and insistent.

These days, that happens far less often. Part of this is due to the splintering of the very idea of “identity culture,” a term that now sounds both quaint and so full of meaning as to be devoid of meaning altogether, and part of this is because what was once considered genre fiction (back when ethnicity was considered a publishing genre) has become so diffuse and complex in its content and practitioners that marketing to an imagined group of readers who you hope are united in their interests simply because of their race seems silly. I suppose the only thing a house can and should do when publishing a book by any kind of minority is to treat them as nothing more or less than a single representative of the American culture at large.