Craft

A Writer Learns to Die

What happened when I had a heart attack in the middle of my MFA

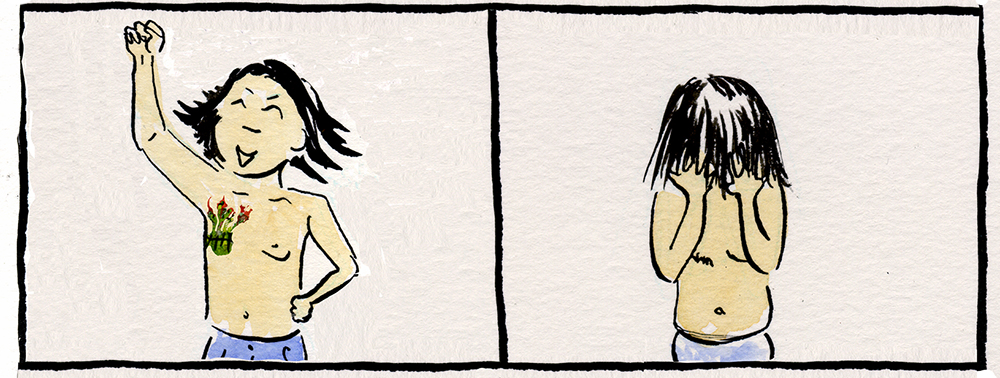

Whenever I think of my heart attack in late September of 2017, I think about my mother’s cardiac arrest in July of 2000. When it happened, she called out to my family and me: “I’m dying and no one cares,” as if she were in one of those TFC dramas that she enjoyed. I was ten when I dressed my mother for her last hospital ride in the flimsy gown that she wore whenever she went: browning at the edges with the smell of hospital sheets mixed with body odor lingering in the front. My mother died when we were halfway to Princeton hospital. She’s had lupus since she was an adolescent, family members told me. Perhaps I carried it too. So when I woke up that early September morning — clutching my chest, breathing heavily, and sweating — I thought of her and dissociated myself from my basement room in Tuscaloosa. I was 28. Yet I was feeling very much like dying. It was here. It was happening to me.

For a while, I thought it was just a severe case of heartburn from the wine I had the night before. I took a cold shower, tried to slow my breathing, and laid on the living room couch hoping it would pass over. After stewing for a few minutes, I called out to my roommate Reilly who slept in the next room over. Although Reilly’s a heavy sleeper, I had to only mention “help” and “heart attack” in the same uneven breath for them to burst out of their room. While this would probably go down as one of the worst things to happen in my life, at least I’d have the company of a fellow writer. We were both in the University of Alabama’s MFA program, having trekked from our Northeast homes to the South so that we could evolve from writers to Writers by doing things such as living just shy of the national poverty line, finding our narrative voices, and applying for food stamps. Reilly is a poet from Baltimore who has specific opinions on Instagram poetry and romantic notions of cowboys and the West. They’re quick to share a drink and offer feedback on a project, often dissecting the meaning behind lines on a page that others would miss. They put as much sensitivity and care into the people they befriend as they do in their poetry. They were also the person to look at my condition and grab their keys without hesitation. “Let’s go,” they said.

While this would probably go down as one of the worst things to happen in my life, at least I’d have the company of a fellow writer.

Reilly’s Prius zoomed eastward, pushing 80 miles per hour on Jack Warner Parkway — I kept the windows down, allowing the 3 a.m. wind to blow back my greasy hair, unable to move most of my upper body except to wheeze deeply. “Everything’s going to be okay,” they said. I kept my eyes to the outside towards the dark of Tuscaloosa, occasionally I glanced back at Reilly, focused and alert, with the hospital’s route memorized. I turned to my side and saw my mother in the red dress and necklace that she was cremated in. She sat in the same place I was when I was ten; we just traded places.

“This is how I went out too,” she said. She was much paler than I remembered her, for a Pinoy anyway. “Maybe you deserve this.”

Maybe I did.

Reilly swerved into the DCH hospital ER driveway from the wrong side. A haggard white man in a hand-me-down security uniform stuck his head out of the air-conditioned sliding doors.

“Going the wrong way, chief,” he said.

I fell out of the hybrid and pulled myself up to reach the door. I was a nuisance — entering the ER from the wrong direction, yelping to my roommates for help, distracting this retiree-looking motherfucker from his infomercial. The guard stopped me in front of the metal detector. “Put your cell phone in the bucket and pass through.” I did as he asked but the metal detector wasn’t even working.

At the sign in desk, the triage nurse asked me what was wrong.

“I’m having a myocardial infarction,” I said.

He took out a sheet of paper attached to a board.

“Sign in please,” he said.

I scribbled an M on the sheet and sat across a group of sorority women and a man in a grey hoodie. I realized my outfit was a white V-neck undershirt and workout shorts, sleeping attire. The shirt, see-through for the most part, exposed my girth sticking out from my sides, my chest, and was probably stained with the occasional blood spot from a bug bite or a scratch.

“Holy shit,” one of the women said, stifling in laughter.

Not holy but definitely feeling like shit, I held the left side of my heart with my right hand and placed my left arm across my chest to cover up. I did this until the nurse called my name. After a series of tests, the ER doctor said that I had to be admitted. “You need to be seen immediately,” she reiterated. “You could very well die today unless we have you go through a stent procedure.” I could ignore her, but that would be rejecting professional medical advice. Who rejects professional medical advice?

If I’d gone out then, it wouldn’t have been so bad. There has been a lot of good in my life. I’m in a relationship with an amazing woman, I got into a fully-funded MFA program, and before that, I spent the past six or so years writing novels. Those works will never see print, but that’s just all right.

One of the books that I enjoyed over the years was Roy Scranton’s Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization. A former U.S. Army grunt turned Princeton scholar, Scranton’s small and unassuming collection of essays contemplate this dying planet by our hands. One observation is his meditation on death as a Soldier in Iraq:

Instead of fearing my end, I practiced owning it. Every morning, after doing maintenance on my Humvee, I would imagine getting blown up, shot, lit on fire, run over by a tank, torn apart by dogs, captured and beheaded. Then, before we rolled out through the wire, I’d tell myself that I didn’t need to worry anymore because I was already dead.

The rest of the book is pretty optimistic.

I practiced dying in that hospital — in the ER waiting room, on the operation table, and on the bed of the chest pain unit. I thought of likely scenarios that could arise in the next 168 hours post-surgery that could find me in an urn like mom. It was not the first time I thought about death (by my attempt or by accident), but now it was close, tangible. All I had to do was touch my chest and feel my heart roar until it clogged and stopped. This vessel of fat, water, and blood I call my body will depreciate; eventually, it will die, then rot, until I am nothing except a memory to a handful, or perhaps, one person.

I practiced dying in that hospital — in the ER waiting room, on the operation table, and on the bed of the chest pain unit.

I envisioned choking on my saliva and shitting myself to death (and subsequently feeling bad for the person who would have to clean that up). I imagined being able to move after the stent was in place, and suddenly my artery rupturing and bleeding to death. I thought about Reilly picking me up at the hospital, getting a beer with them at a bar; I say “Looks like the MFA almost killed me,” and when I leave to take a piss my heart gives out, not because I’ve been drinking but because I’m a fucking wild idiot, and I die by slamming my head on the bathroom tile. I thought if I fell asleep I wouldn’t wake up again.

After I was admitted, I didn’t see my mother as an apparition or in my dreams. I thought the surreal events of the last few hours would bring her up again, but she never visited me. Late at night, tired and decompressing from the stent, I thought about whether my life had any worth. I came all the way here from Jersey just to write and then die? Should I have stayed my brown ass up north? Should I have listened to my partner, a woman smarter and wiser in me in every way, and taken my time with my work instead?

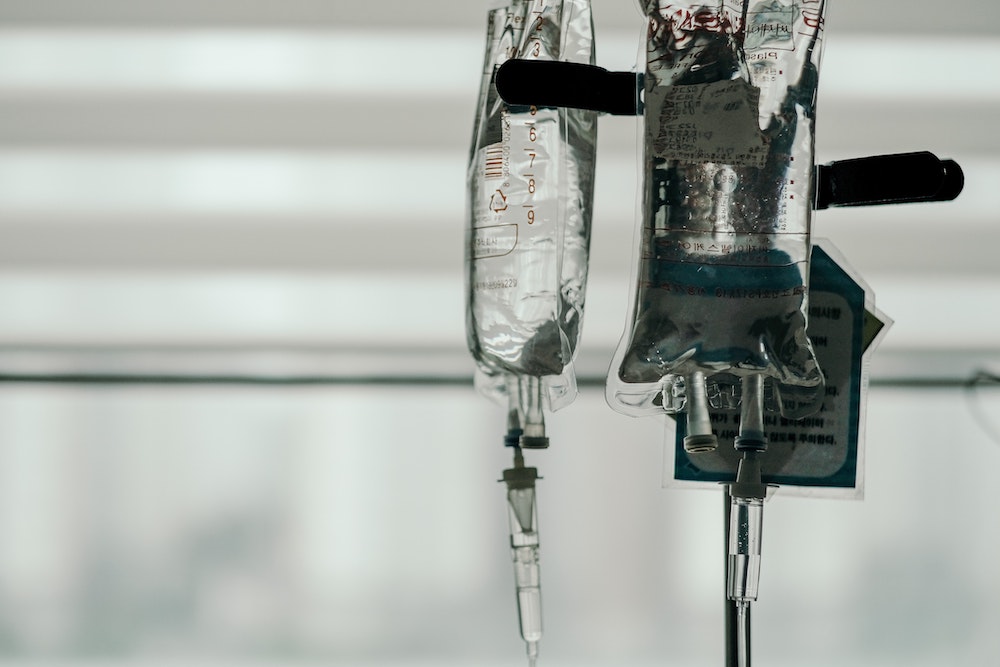

For the stent procedure, I laid on my back, focused on a bright light as one of the operation technicians shaved off the twisted gloomy jungle on my groin with an electric clipper. “This is for the operation,” she muffled through her surgical mask. I looked to my left to see aides stretch out disposable gloves. People spoke in monosyllable tones. Staccato commands. Machine checks. I’d seen this all before except when it happened to mom, there were gloves and gear all over the floor; no murmurs then, only shouting, the flow of automated machinery.

“While you’re down there,” I said to the technician, “do you mind getting the entire thing?”

She laughed, but I bet they’re trained for patients like me — dazed, slightly nervous, and wondering how they got here. They’re taught to look the patient in the eye and smile, reassure them that everything will be OK. Whether you’re an executive or writer, whether you’re too young or too old to pass, on the operating table those things don’t matter, you’re just. As she finished up, the cardiologist hovered over me. His breath was slightly askew, but he was cordial. He said his name, his profession, and what he was about to do. This is another stranger that holds my life. I have minor heart issues. You’re only a child. So sad. You’ll be fine. You’ll wake up with a stent. Stent. It’ll separate your clogged artery.

'Why Is Illness What Makes You See Us?'

He’s such a good guy. The woman who shaved me said that he is the most compassionate physician in town. But good guys can fail to save the dead just as much as bad guys or the guy who tips 10% or the guy who double parks in a grocery store parking lot. I planned my obituary on the operating table: Filipino American, first-generation, male, 28, never did much for society as a whole, owes an apology to a lot of people. Once entered and lost a hot dog eating contest to a black man dressed up like Hulk Hogan. Once got accepted off the waitlist of a state university to have the space to write, learn, and sort-of/kind-of got paid for it. Once believed in God.

I closed my eyes and woke up in a room with fluorescent lights.

There are other things I could talk about that weekend too. The excellent nurses who took care of me (shout out to nurses Nanette, Clayton, and the entire DCH CPU staff), the time when one of them had to remove the catheter that was inside of me by pressing down on my groin for thirty minutes while another nurse cheered me on — you’re so strong, just a little bit more! — or the surprisingly good quality of Tuscaloosa hospital food. Also the medical bills; so many fucking bills.

I was discharged on Sunday after meeting with the hospital physician who said I had a minor heart attack, a nutritionist who told me what I could find online, and my cardiologist who told me I actually had a full blown heart attack and that I should change everything in my life. I was told to take it easy, although they understand I’m in graduate school. I was told to avoid red meat. I was told everything will turn out fine.

I was told to take it easy, although they understand I’m in graduate school. I was told to avoid red meat. I was told everything will turn out fine.

The cardiologist prescribed a total of five medications, four of which I need to take every day. “Either you take these pills,” the nurse said, “or your artery will clog again, and we’ll see you back here.”

Reilly picked me up from the hospital, and we didn’t talk about the tube that went through my groin, the shaving, or my rambunctious weekend. We went to Rite-Aid and picked up their photographs and my pills.

“That was pretty fun,” I said to Reilly.

“Yeah,” they said.

“What do you think did it?” I asked them.

Reilly drove on, and I thanked my roommate again.

When I arrived at the house, I put my pills away and sat down on the couch, facing the portraits of dead flowers that Reilly repurposed as art. I tried to think of the last time my family visited my mother. In the evening, my partner and I had a discussion over the phone that was partially sympathetic but also prescriptive and scolding of my eating habits and drinking. It circled back to forgiveness and understanding of my condition and our distance but I believe we came back to this because of our close bond. Alone in the dark, I went to work and edited a short story that was due that evening only to have it turn around a few days later with a form rejection. I was frustrated about that until I interrogated my feelings of writing, of craft. What is the practicality of writing at the expense of your health, the ability to pay for it, or to care for those you love?

What is the practicality of writing at the expense of your health, the ability to pay for it, or to care for those you love?

As Scranton wrote in the essay “A New Enlightenment,” coming to terms with dying is about meditation on the self.

Learning to die is hard. It takes practice. There is no royal road, no first-class lane. Learning to die demands daily cultivation of detachment and daily reminders of mortality. It requires long communion with the dead. And since we can’t ever really know how to do something until we do it, learning to die also means accepting the impossibility of achieving that knowledge as long as we live. We will always be practicing, failing, trying again and failing again, until our final day.

I visited death taking my mother on the car ride to Princeton. I felt its touch on the operating table in Tuscaloosa. I pay homage to It whenever I go into a pharmacy and spend fifty dollars on prescription pills or make payments on preventative care just to keep me breathing. I read about Its slow violence on Black Twitter whenever another black or brown body is murdered, detained, or incarcerated at the hands of Federal officials, a police force, a white nationalist. I don’t have to look far to be reminded of Its embrace.

Yet I am fortunate in the small victory that I still exist. I breathe. I wake up in the morning to make generic coffee and write. I go on long walks listening to library audiobooks, strolling through a campus failing to address its past. I read and take notes on good writing. I go online. I discuss the days of my partner who lives a thousand miles away from me, a woman full of life and love. And once the night is really still — just the low drum of my humidifier or the trains braking hard by our house — I recall how this day has ended to give rise to another and the cycle continues.

Perhaps the pursuit of finding continual purpose and joy in life does not exist in feeding whatever selfish understanding I once had of my writing. Perhaps it exists within other means, such as giving voice to those who weren’t elevated before, and celebrating the works of others who deserve it; perhaps it is in giving back by lending a hand or an ear; perhaps it is in the shared communication with my partner and me, with friends, with strangers — a consistent ebb and flow of shared experiences in order to build memories. My life may not mean much anymore, but perhaps my physical body, my conscious, can be a guide for future generations of others like me. The ones I care about. The ones I love.

My life may not mean much anymore, but perhaps my physical body, my conscious, can be a guide for future generations of others like me. The ones I care about. The ones I love.

As Scranton writes towards the end of his essay collection, memory is the only thing that can save those who are already dead. Perhaps whatever medium I end up writing in will become an addition to the conversation of being a Filipino American, being a human, being me, today. My memories laid out in prose are attributed to those who helped me live and continue to sustain my existence. As I practice revisiting my mother’s end and the inevitability of mine, I will impart pieces of her life into my own, tucking away memories of her: her parting, her care, her hope for a better life beyond our world, her fears, her nurturing, her anger, her humanity; through my small attempts at writing and sharing with an audience, someone can be there to remember her; someone will be there to care.