Books & Culture

About Literature

by Gabi Gleichmann

I lived in Hungary for the first decade of my life, back when the country was held in the steely grip of the Communist Party and the truths of the authorities could never be questioned. The media were controlled by the state, and journalists were accomplished liars about everything except the scores of soccer matches.

Those seeking truth had to resort to works of literature

, even though the official censors kept a close watch on such publications.

In search of the few available crumbs of truth, my parents bought copies of all new novels and poetry collections published in the country. Our home was like a library, piled high with books, and my first vivid experiences of the world of books were purely sensual delights: the smell of paper and printer’s ink, the nuanced colors of the book jackets. Later, once I’d learned to read, I traveled, powered by the fuel of the alphabet, to inner and outer worlds, down into the depths of history, sometimes into the future, toward the vast riches of life that extended farther than any eye could see. I spent time with people who had lived long before me in places I would never be able to visit; perhaps those places had never existed at all. I often curled up under the covers to read, living in a boundless world of dreams, full of adventures.

For a long time my favorite book was One Thousand and One Nights, that perpetually enchanting cocktail filled to the brim with the most delicious ingredients of the Middle Eastern storyteller’s art, spiced with liberal doses of invention and humor, sensuality and cruelty. Sometimes I would skip school, preferring the company of Aladdin, Ali Baba and Sinbad the sailor. One time I was caught and as my mother seized me by the ear, I couldn’t help exclaiming, “I wish I was grown up already and could spend all my time just reading, reading and reading!” Perhaps that episode was influential in my decision ten years later to dedicate myself full time to a life in the world of books.

My next tumultuous literary experience came in my late teens when I read The Trial. It was earth-shaking for me. With just the first few pages I realized that I adored Kafka, especially the tension between dazzling light and absolute depths of darkness that characterized his prose. More than anything else I was impressed by his conversational style, recognizable for its simplicity and crystal clear transparency. And I took his motto for my own: “Correctly comprehending a thing is no guarantee that one hasn’t failed to understand it at the same time.”

Kafka the strict moralist became my guide, one who pointed out the right path but never disclosed the goal.

That great prophet of ambiguities taught me to look at the world with fresh eyes and without illusions. Reading Kafka gave me insight into myself; I discovered that I’m a complicated, eclectic and urban Jew, one who believes in no God but still has spiritual needs, and, I hope, has a moral dimension: a man who accepts uncertainty as the only constant and change as the only certainty.

Others who have enriched my world are the great writers of Latin America. Gabriel García Marquez and Mario Vargas Llosa have taught me that within a work of the imagination everything can exist simultaneously and on the same level, outside our familiar sense of chronology, with no distinctions drawn between the realistic and the fantastic or between reality and myth. Their approach allows one to create a world complete in itself, a landscape in which everything leaps into view as if lit by a flash of lightning.

I’ve lived my whole life surrounded by novels, works of the imagination and invented stories. The question therefore presents itself: Why, exactly, do I read and write?

As far as I’m concerned, reading and writing serve the same purpose. They help me to come to grips with myself and with the world around me. I read and write to see more clearly, to fully develop and to exactly express my feelings and thoughts. I do this above all in order to explore and to encounter — not things that I already know, but instead those that still remain obscure to me, half intuited and virtually unknown. For I aim to push my way into that hidden reality and perceive things in new ways. In such an endeavor, not even cutting-edge psychological research can come close to what poetry can achieve.

I am never alone when I read or write, even though a casual observer would see these activities as elements of a profession practiced entirely in isolation. In a different sense, however, they provide one with an ample and rewarding circle of acquaintances. When I read, I enter a world conceived by another person, and when I write, I am reaching out to my fellow human beings. These tasks sustain and uplift my spirit by extending its worlds of fantasy, feeling and play. In literature nothing is sacred. Its works are the products of dreams, thoughts, feelings and fantasies that never petrify into dogma.

Literature is the eternal conversation of the human race.

Beside, literature is the only tool we have to give back the face and the life of dead people who has fallen into oblivion.

***

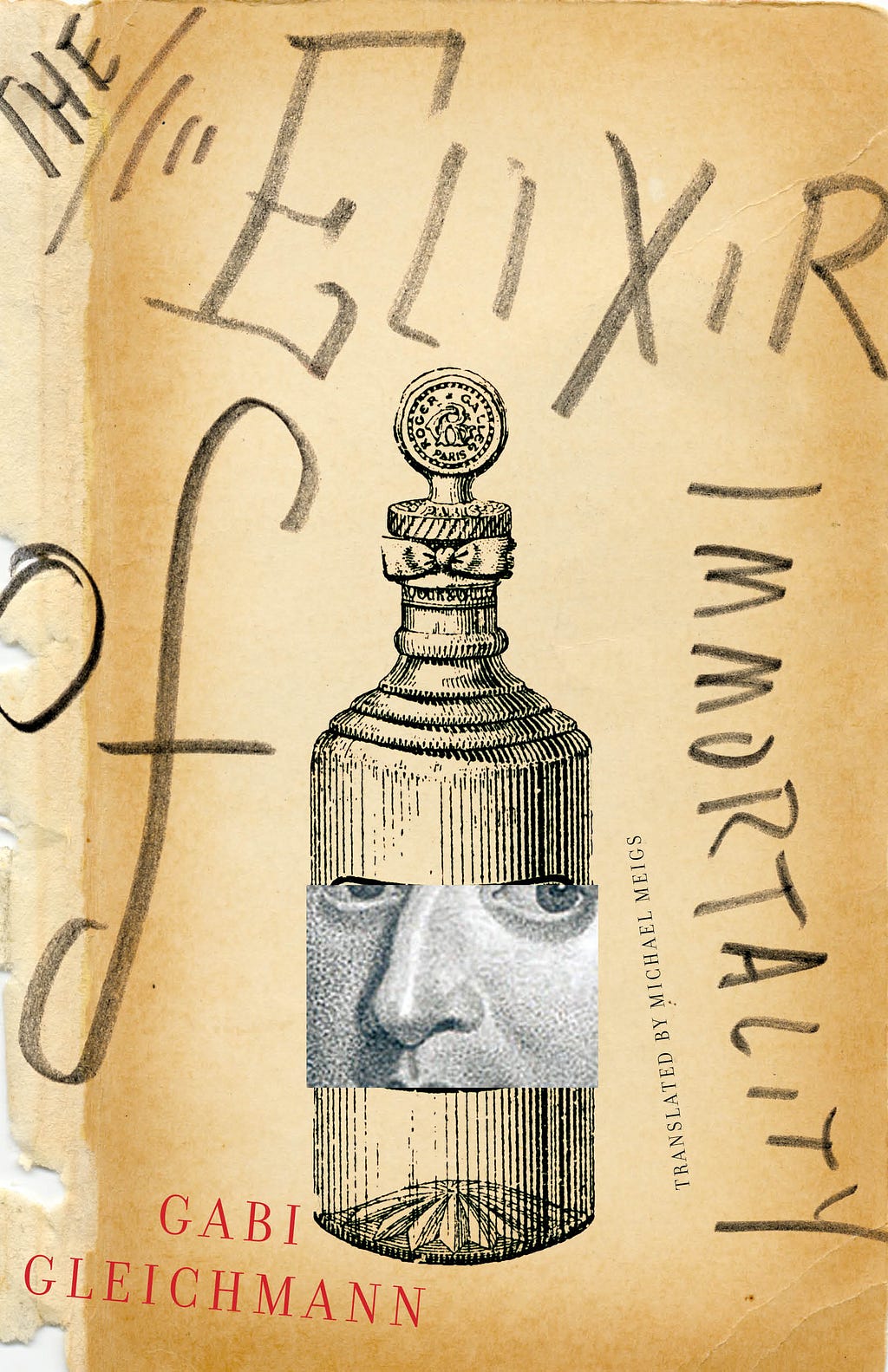

— Gabi Gleichmann was born in Budapest in 1954 and raised in Sweden. After studies in literature and philosophy, he worked as a journalist and served as president of the Swedish PEN organization. Gleichmann now lives in Oslo and works as a writer, publisher, and literary critic. His first novel, The Elixir of Immortality, was sold to eleven countries prior to its first publication.