Books & Culture

Against Worldbuilding

Why “worldbuilding” is the most overrated and overused concept in fiction

Forget plot or characters. Don’t worry about voice or structure. If you believe the internet, there’s nothing more important in fiction than worldbuilding. “Every story requires” worldbuilding, which is “is an essential part of any work of fiction” and “the very essence of any good fantasy or science fiction story.” What once was a term used for a certain strain of second world fantasy fiction has spread across cultural criticism, and is heard in university literature classes and video game reviews in equal measure.

@egabbert thanks. i’ve noticed lately anytime students don’t understand something they think it’s sci-fi & try to assess the “worldbuilding

Not long ago I was at a reading for the fantastic short story writer Kelly Link. The first audience question was “How much worldbuilding do you do for each story?” I’ve heard this question asked of many short story writers (myself included) of different genres and styles.

While worldbuilding is an important part of some types of fiction in a couple genres, it’s a largely counterproductive concept for most types of fiction

Worldbuilding vs. Worldconjuring

As a reader, I’m most drawn to writers that invent new realities or tweak our own world into bizarre new shapes. My problem is not with non-realist writing, but in applying the rules of certain types of science fiction and fantasy to all types, and beyond. But what is “worldbuilding”?

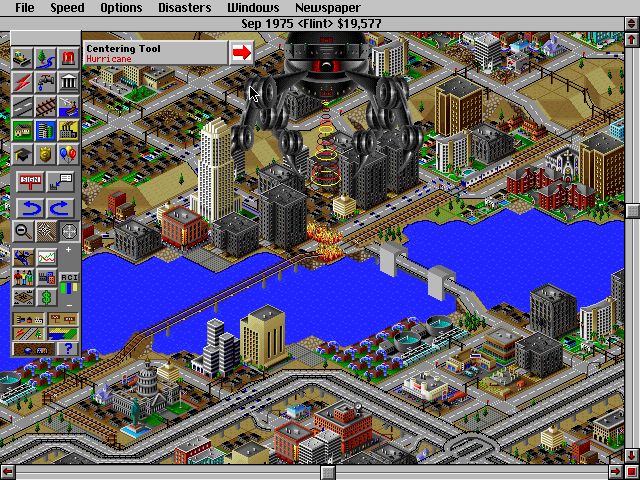

Some people will argue, tautologically, that all fiction takes place in a world and thus all fiction worldbuilds. But the way most people use the term is similar to what Chuck Wendig’s definition: “[worldbuilding] covers everything and anything inside that world. Money, clothing, territorial boundaries, tribal customs, building materials, imports and exports, transportation, sex, food, the various types of monkeys people possess, whether the world does or does not contain Satanic ‘twerking’ rites.” Worldbuilding is not merely creating a fictional setting and writing a narrative in it. It is an attempt to flesh out an invented world in way that allegedly feels “real.” In a perfectly executed work of worldbuilding, there would be no gaps in the world for the reader to fill in. Everything from the goblins’ favorite type of baby wipes to the export taxes on Martian ray guns would be worked out (at least in the author’s mind if not on the page). This is not possible, but worldbuilding expects the author to have “rules” that are “logically” followed to their conclusions.

Everything from the goblins’ favorite type of baby wipes to the export taxes on Martian ray guns would be worked out (at least in the author’s mind if not on the page)

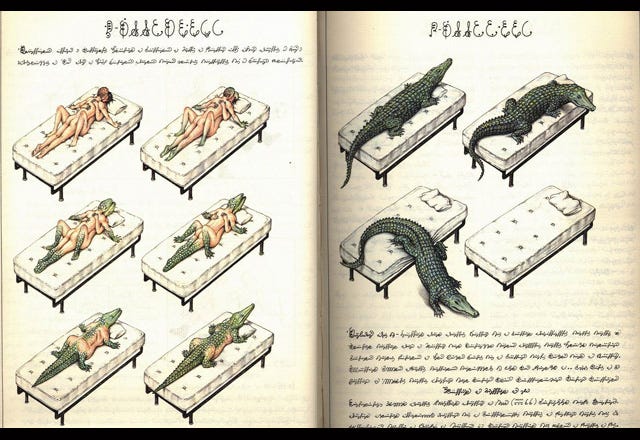

In contrast to “worldbuilding,” I’ll offer the term “worldconjuring.” Worldconjuring does not attempt to construct a scale model in the reader’s bedroom. Worldconjuring uses hints and literary magic to create the illusion of a world, with the reader working to fill in the gaps. Worldbuilding imposes, worldconjuring collaborates.

Let me make a necessarily incomplete analogy to another platform. In painting, worldbuilding is like Renaissance art that attempts to create realistic figures even when they are cherubs, demons, or god. Worldconjuring is a spectrum of other techniques: Matisse implying dancing figures with a few swoops of the brush, Picasso creating a chaos of objects to summon the horrors of Guernica, Magritte shattering our vision with impossible scenes. We should enjoy realistic paintings, but we shouldn’t impose their standards on every school of art.

Worldbuilding is The Silmarillion, worldconjuring is ancient myths and fairy tales. (In fairy tales, we don’t learn the construction techniques of the witch’s gingerbread house or the import/export routes of evil dwarves.) Worldbuilding is a thirty page explanation of the dining customs of beetle-shaped aliens, worldconjuring is Gregor Samsa turning into a beetle in the first sentence without any other fuss.

All stories may need to conjure a world, but only a few benefit from building one.

All stories may need to conjure a world, but only a few benefit from building one.

What Worlds Need Building?

At the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America page, Patricia C. Wrede offers a large list of worldbuilding questions for writers such as “How early do people get up in the morning in the city?” and “What shapes are tables/eating areas (round, oblong, square, rectangular, etc.)?” Wrede doesn’t expect authors to know all these questions, but they give a good idea of the level of detail at which many worldbuilding authors are asked to think.

What kind of fiction needs such details? A prime example might be A Song of Ice and Fire, where the varying religions, political factions, and regional customs are indeed a huge appeal of the books. It’s also no coincidence the series is massive. As we’ve pointed out before, the current five books (of a planned seven) are 12 times as long as One Hundred Years of Solitude, 36 times as long as The Great Gatsby and more than and 80 times as long as The Metamorphosis. As a general rule, the longer we stay in a world, the more worldbuilding might be necessary.

Even in epic fantasy stories, though, it’s questionable how much detailed worldbuilding improves a work. Tolkien is revered among worldbuilding obsessives for going to such lengths as inventing complete languages for his fictional races before even writing the story. Contrast that with George R. R. Martin, who famously describes himself as a “gardener” instead of an “architect,” and who simply makes up some fake words and lets the reader infer the rest. Readers may prefer one series to the other for a variety of reasons, but I doubt one reader in a million prefers The Lord of the Rings because dwarven has more realistic grammar than Dothraki.

And plenty of great fantasy books fall outside of this kind of faux-realistic worldbuilding. Marquez’s brilliant and epic One Hundred Years of Solitude is filled with magical happenings, but the magic exist for metaphorical and poetic effect. One character is constantly followed by yellow butterflies, but there is no explanation for this. There are no “rules” governing who gets butterflies and who doesn’t.

And for all the worldbuilding love that The Lord of the Rings gets, Tolkien’s work would fail the worldbuilding guides I’ve linked to here. He may have set the table for high fantasy, but he doesn’t even pass contemporary fantasy author Brandon Sanderson’s first “law’ of magic. The focus on worldbuilding has moved far beyond simply creating some interesting backstories and complex politics to increase the drama of the tale, to expecting a writer to have mapped out every detail of a world as if they were producing an encyclopedia instead of a story. Would the mythic The Lord of the Rings be improved by more discussion of elvish trade agreements and Mordor dining room etiquette?

Was Star Wars improved by midichlorians and trade negotiations?

A Crazy Fan Theory about Crazy Fan Theories

The problem I see with worldbuilding is that readers have come to expect books to meet a standard that the author can’t possibly (and probably isn’t trying to) meet. When I’ve taught fiction classes, I’ve often seen that when students encounter a book outside of the modes of actual realism or faux worldbuilding realism, they don’t know how to evaluate it. They believe that a different way of seeing reality aren’t invitations to see reality in a new way yourself, but simply failures of worldbuilding.

(As an aside, it isn’t a coincidence that the celebrated SFF “worldbuilders” are Western writers, typically white, while imaginative writers from so many other cultures get lazily lumped together as “magical realism.” Worldbuilding insists on a certain concept of supposedly logical “realism” that pretends it is the only way to see the world.)

At the same time, fans of worldbuilding works focus not on the arc of the story, the struggles of the characters, or the aesthetic power of the fiction. They focus on the inevitable moments when worldbuilding breaks down. My least favorite example of this is the “crazy fan theory.” These normally begin on a site like Reddit, then spread like Kudzu across the internet. Why didn’t the giant eagles simply fly Frodo to Mount Doom? Well, it would be a really boring story if they did! That doesn’t satisfy fans, who instead create fan theories that “explain” and “fix” and “change the way we see” famous works like The Lord of the Rings. (These crazy fan theories exist for basically every popular book or movie that has ever been produced.)

The urge to “fix” or “explain” art is one we should always be suspect of.

“Bad Worldbuilding” Is Just Bad Writing

None of this is to say that there aren’t many stories that are poorly written. That are set in dull worlds with corny characters and unoriginal plots. But are these problems truly one of worldbuilding? Take Charlie Jane Anders’s often-referenced “7 Deadly Sins of Worldbuilding.” Anders is a great writer and a smart critic, and I agree with the substance of almost everything she says. One dimensional alien/fantasy cultures are lazy and lead to bad fiction. Stories need a sense of why the events are happening now and not some other day. Anders’s advice is solid.

But do we need “worldbuilding” as a concept to explain why moral simplicity, characterization without nuance, or a lack of a tactile sense-of-place can be a problem? A work of fiction set in 2017 will also be bad if the characters lack nuance, the political messages are heavy-handed, and the story is wrapped up in an overly-logical bow. Good writing is complex and ambiguous, not simplistic and heavy-handed.

But do we need “worldbuilding” as a concept to explain why moral simplicity, characterization without nuance, or a lack of a tactile sense-of-place can be a problem?

At the same time, the appeal to “realistic” portrayal of alien or magical beings doesn’t have anything to do with realism. Magical creatures don’t exist! If aliens exist, we don’t know what they are like yet! Human history doesn’t illuminate the history of fictional creatures. It’s quite possible that an alien race might have a monoculture, and the creatures of actual mythology and folklore were often portrayed simplistically. The call to make make such races more complex is not to make them more “true” to the reality of dragons, Martians, or giant eagles. It is a call to make them more human, and thus more interesting to human readers.

Storybuilding Vs. Worldbuilding

Ultimately, the logic of worldbuilding always succumbs to the more important logic of storytelling. George R. R. Martin liked the idea of a planet that goes through decades-long winters, but he also wanted it to seem like medieval Europe with similar wildlife and political structures that would, in “reality,” not survive decades of winter. What matters in a story is the story, and what serves the story is useful. The Machiavellian political struggles of Westeros are the story of ASOIAF, and so the complex politics of the region matter where the grammar of Dothraki or the breeding habits of Westeros mammals do not. The mythic sense of civilizations passing is part of The Lord of the Rings, so the history of the races and kingdoms matters even if their biological plausibility doesn’t. Harry Potter’s class might be a fraction of the size it should be, but the small cast of characters works better for the story that Rowling wants to tell.

It isn’t a world that a writer is creating, it is a story. The goal of the writer is not to clutter the path with every object they can think of, but to clear the way for the reader’s journey.

The World of Fiction Beyond Worldbuilding

The main reason I think worldbuilding has become a problem is that it leads people to believe that “realism” is the primary point of fiction, even fantasy fiction. But representing reality — whether “real” reality or a fictional one — is simply one way of telling a story, just one house in the city of fiction. Surrealists, magical realists, post-modernists, and countless other movements or styles create fantastic worlds that function on other levels — mythic, philosophical, Freudian, etc. — that are at odds with this idea of worldbuilding.

Representing reality — whether “real” reality or a fictional one — is simply one way of telling a story, just one house in the city of fiction.

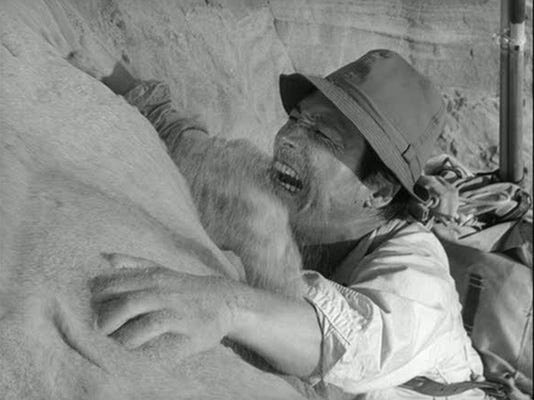

One of my favorite novels is The Woman in the Dunes by Kobo Abe. It’s about a man who misses his bus while looking at insects at the beach, then gets tricked into living in a village where each house lies in a big hole in the sand. The villagers spend their days on the Sisyphean task of shoveling sand to avoid being buried alive. The book is amazing, thought-provoking, and bizarre. And it could only be ruined by worldbuilding (how could such a village survive in modern Japan without being discovered? Wouldn’t sand actually just collapse on all of them?) You have to accept it on its own terms.

Julio Cortazar is not failing at worldbuilding by not describing the tax rate of vomitted rabbits, nor is Ray Bradbury violating the rules of SF by having the implausible buildings on Mars. They are simply doing something different.

The reader who expects worldbuilding is frequently the reader who expects fiction to have “answers.” The one who wants all mysteries to be solved, all stories to have “a point,” and all ambiguity to be swept under the rug. Worldbuilding may expand a world, but the concept is narrowing the paths available to writers and to readers.

UPDATE: I’ve published a follow-up article that addresses some of the questions and critiques in the comments here. If you want to argue more about goblins and aliens, give it a click!

More Thoughts about Worldbuilding and Food