news

American Twang with Mark Twain: Bushwick Book Club

A

Google “Mark Twain” and traipse a bit around the internet. You will stub your toe repeatedly on the marriage of “quintessential” and “American.” You will find epigrams transcribed from telegrams, mustaches and homespun maxims, posthumous paeans galore. Twain’s scorn, in all its tartness, will blazon from prominent places. You will find websites wallpapered in ochre, umber, and other earthy tones. The tuxedos will be white, the general air breezy. You are not stupid. You know the whole pose is — at some level, to some degree — just that: a pose. But there’s something about it. It feels true.

There’s a good chance you and I are similar in this: it was in school, and only in school, that you read Twain, and yet you feel you know him as well or better than many of your favorite authors. I attended the most recent installment of the Bushwick Book Club’s monthly series, a slightly early celebration of what would have been Twain’s 177th birthday. Riding the train home, I scribbled a question in my notepad: What — not who — is Mark Twain?

1. Ben Arthur channels his inner spinstress 2. Susan Hwang working the bellows with Leslie Graves

If you had to explain Mark Twain to the uninitiated — that is, to the young, truant, or foreign, Twain being a staple of American education — you would say he was a writer. True. But his great gifts had very little to do with writing as a technique, a trade. Social acumen, quotable wit, prescience in so many moral matters, the empathy and courage to embrace colloquial America without the condescensions of the educated class — here he won his bread; craft was vessel, not focus, and emphatically not ornament. None other than Hemingway, another gray-whiskered, looming patriarch of literary “Americanness” wrote, “All modern American literature comes from one book… Huckleberry Finn.” Twain followed his masterpiece with nine more novels, countless essays, four collections of short stories and two of nonfiction, not to mention all the books, including a 2000-page autobiography, published after his death. By critical consensus, these works are for the most part crippled by self-indulgence, sentimentalism, and, ironically, verbosity. Dogged by debts of his own rash making, he hit the lecture circuit, the gentlemen’s club circuit, the post-banquet comedy circuit, and foreshadowed another new American identity: the modern celebrity.

At the Bushwick Book Club’s monthly installation, it was fitting that the heartiest guffaws were got from quotes like this:

I haven’t any right to criticize books, and I don’t do it except when I hate them. I often want to criticize Jane Austen, but her books madden me so that I can’t conceal my frenzy from the reader; and therefore I have to stop every time I begin. Every time I read Pride and Prejudice I want to dig her up and beat her over the skull with her own shin-bone.

George Orwell was not so far off when he said Twain wore “the amiable mask of… the licensed jester” and “became that dubious thing: a ‘public figure’ flattered by passport officials and entertained by royalty.” In his old age, Twain did become an eensy bit of a shill, his cantankerousness at times self-conscious and transparent. Indebted, he flexed his mind for money; before mass media it was of course the moneyed classes who could afford him, whom he could not, fearing bankruptcy, offend. But Twain always had his eye on fame — didn’t Samuel Clemens christen himself anew? Despite a mutual affinity for the unembellished word, Orwell could not get the American writer any more than he could get America. The relevance of Twain’s characters to distinctly American conflicts, neuroses, hypocrisies, and sublimities is beyond the uptight Brit. The relevance of Twain himself? Of Twain’s self-creation, his mythologizing and romanticizing, his celebrity? Forget it. Uber-Anglo that he was, Orwell dismissed pre-Civil War America as mere history, a quaint blip to be recorded for journalistic posterity and then closed forever, so important shoulders hoisting important minds could once more hunch over The Book of Common Prayer.

The man behind Doublethink, furthermore, would have balked at The Bushwick Book Club’s name — it’s not a book club at all! (Or is it?) At Wednesday’s event, plenty of books could be found at the Table of Twain; Twain entered the room as musicians shared favorite passages; while musicians tuned and intubated their instruments it was Twain’s words we listened to. But aside from these letters, and Twain-related stage banter, the ghost was in the tunes. Music? At a book club? That’s right, kid — the BBC is a book club of a different stripe. Since 2009, they have hosted gatherings dedicated to a particular author. Each month, a cadre of tenderfeet and BBC veterans perform original songs based on, inspired by, and/or dedicated to a particular work of the author’s, to a general theme of the author’s, to the author himself, etc. etc.

We gathered downtown, at Housing Works — a bookstore, a café, and a beautiful thing. The sitting area had been cleared, the chairs unfolded in rows. By the time we began, a solid 60 people sat facing the stage and flanked stage-right, filling all seats in view. Host and performer Susan Hwang hopped up behind an array of speakers, three mic stands, and four bottles of water, which would go untouched and, later, would be joined by a can of Six Point. She slipped on an accordion, joined onstage by Leslie Graves, who sang harmonies for the night’s first song: a cabaret-ish number riffing on the topsy-turvy eschatology of “Was it Heaven? Or Hell?” Truly, there is no season like the holidays for bringing out the horror that lurks in carols, hand-holding, general contentedness, and whatever other sinless activities with which the blessed pass time, waiting for Judgment Day.

1. Everybody act casual 2. Bluegrass from Danielle and Jesse

The music was pretty fantastic, especially considering the songwriting constraints, and by setting songs side by side with a shared corpus of source texts, BBC offers insights into the varied approaches to songwriting. For his song “Shallow Ports” Peter Dizozza mined Life on the Mississippi, Twain’s recounting of his adventures as a steamboat pilot. He emerged with a danger-tinged piece whose speaker, also a pilot, looks to Twain when the goings gets dire. The music was bolstered by a surprising, brisk transition from devilish A to melodic B section, and Dizozza got a big hand for his efforts. Working from the same text, Ellia Bisker produced a wholly different sort of music. Accompanied by herself on ukulele, her voice gained strength as plucking grew to strumming and the ballad hit its big choruses. In place of Dizozza’s focus on river’s perils, Bisker took as inspiration Twain’s celebration of the pilot’s absolute freedom, and her music and themes accorded.

Getting down on some historically-appropriate bluegrass was BBC mainstay Up Against the Wall String Band. No small amount of serendipity prompted the group’s songwriting; when Daniel (“Danny Danger”) bought his first banjo, the case had a sticker with a Twain quote: “Smash your piano, and invoke the glory-beaming banjo!” Mark Twain, Daniel mused, is kind of a banjo in a world of piano writing, and with that, the duo rollicked into the Appalachian tones of “Smash your Piano.”

Inspired by the combination of Pudd’nhead Wilson and her daughter’s tendency to climb all over her, Stacey Rock’s acoustic lullaby provided a counterweight to the banjo’s glory, which had been beaming all over the place. In a similar vein, Leslie Graves, Hwang’s erstwhile backup singer, sang a song of her own, a folksy showcase for her airy voice. Counterweighing everybody was Happy Rappie. Three of the four Brooklyn rappers came in matching T-shirts. Three of four had pretty hip glasses. Despite falling just short of unity fashion-wise, the group’s solidarity was evident in their rhyme styles, which were straight out of the mid-80’s. From memory and off the dome, they hipped and hopped to — wait for it — The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County. Rap reserves exhausted, the group moved to their coda, reading/crooning to the outro of Clapton’s “Layla.” Not bad, but Jonathan Mann was not to be out-weirded. Backed by midi instruments, he belted out song #1426 in his Homeric song-a-day quest, this one about Twain and Austen, as lovers, fighting off a zombie horde.

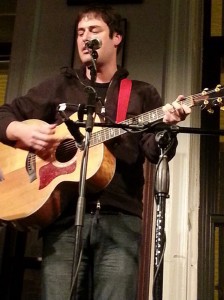

Hwang’s theme of horror lurking in innocence returned when Ben Arthur took on the Widow Douglas’ point of view, and sang about Huck Finn, that rascal. Strumming an acoustic, he crooned: “God left me barren, that’s my luck / now I’ve got you, and I’m stuck / All I can say is ohhh [comedic pause] Huck!”

Arthur’s choice of readings was spot on. No less worthy of mention than the Jane Austen bit was Mark Twain’s advice to writers. Much of it was, well, Orwellian: “Use plain, simple language, short words and brief sentences. That is the way to write English — it is the modern way and the best way. Stick to it; don’t let fluff and flowers and verbosity creep in.” (Note, however, Twain’s skillful rhetoric: hyphen, semi-colon, epistrophe, polysyndeton.) Also: “Substitute damn every time you’re inclined to write very; your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be.” Receiving a collective groan of recognition was the tenth and final commandment: “Write without pay until somebody offers pay. If nobody offers within three years, the candidate may look upon this circumstance with the most implicit confidence as the sign that sawing wood is what he was intended for.” My personal favorite was a letter Twain sent in response to a huckster’s unsolicited patent medicine advertisement. His exasperation is all too relatable in our spam-infused age: “The person who wrote the advertisements is without doubt the most ignorant person now alive on the planet; also without doubt he is an idiot, an idiot of the 33rd degree, and scion of an ancestral procession of idiots stretching back to the Missing Link.”

I recently watched an interview with Woody Allen. The two men have some interesting similarities: towards the end of sustained, productive careers, each — long established as ‘public figure’ — felt the specter of unrealized potential. And Allen, in his own way, is as American an artist as Twain; his America is smaller and more open about its European affinities, but it is no less a product of this country. (Think how he wears his neuroses like badges of honor, as though the mind that cannot be reached by a woman, much less a therapist, is the mind of a true individual.) In the interview, Allen was asked if he would rather live to 98 and finally write his magnum opus — his Bicycle Thieves, his Grand Illusion — or live to 100 and not. Would he forfeit two years of life? Allen’s immediate answer: “No. I would take the two years. Forget the film. I’m not that dedicated… I’d take two months.” Twain died at 74, three years younger than Allen is now, but he outlived both his wife and two of three children. Late in life he was, by all accounts, an unhappy man. Are we to begrudge an accomplished man’s comforts, taken at the expense of that man’s art? Or should we celebrate all he achieved, his many moments of brilliance with the long years of mediocrity? You know where the Bushwick Book Club stands. Which is your America?

Make your thoughts known when the Bushwick Book Club Let’s it Poe on December 20th at Union Hall in Park Slope.

***

— Garon Scott lives, writes and sleeps uneasily in Brooklyn.