essays

Authors Remember David Bowie

As word of David Bowie’s death spread on January 10, 2016, heartfelt messages of grief and remembrance poured out from around the globe (and from outer space). The impact of the incredible, multi-talented Thin White Duke on so many cannot be denied. Communities of those mourning his loss have been gathering to celebrate his life with dance parties, silent tributes, and grand concerts still in the making.

David Bowie paved countless creative paths, opening doors for generations to follow. Fellow musicians, visual artists, writers, and others have been inspired by his work, often finding the permission in his music to push a little further toward their own unique selves.

We asked several writers to share their thoughts on David Bowie — their memories of favorite songs and albums and moments that helped shape their lives and, in many cases, directly impacted their own writing.

Aleksander Hemon, author of The Making of Zombie Wars, Behind the Glass Wall, and The Lazarus Project, among others

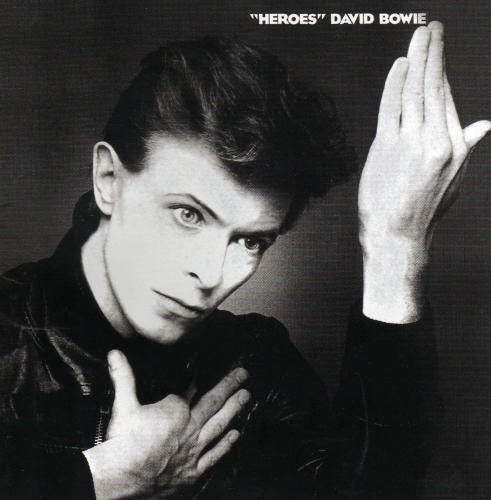

Heroes (1977)

In 1977, I was thirteen and already deeply invested in music and art and everything and anything that would help me understand and formulate my complicated, confusing adolescent feelings. I was about to make a leap in that pursuit from the portentous pretentiousness of bands like Pink Floyd, Yes and Led Zeppelin to the brutal, confrontational simplicity of The Sex Pistols and The Clash. I was about to start wearing a lot of torn denim, assert my right to listen to any music I found interesting (which my harmonious father collectively referred to as struganje — scraping). I was about to confuse rage and rebellion, nihilism and desire for change, complaining and thinking independently.

But, in 1977, someone gave me David Bowie’s Heroes for my birthday. It was — and is still — a brilliantly strange record. The black-and-white picture on the cover, Bowie frozen in a gesture that for all its mesmerizing drama could not be interpreted. The tunes based on riffs and patterns played by instruments that could not be fully identified; songs lacking choruses or the clarity needed for radio play time, a few of them nothing but synthetic soundscapes; the lyrics that made no statements, offered no guidance (“Joe the Lion, made of iron/went to the bar/a couple of drinks/and he was a fortune teller”) and were of no help to me in formulating anything about me. And then “Heroes,” the song, which had to do something with love and freedom and the Berlin Wall, devoid of a chorus and strung on Robert Fripp’s guitar wailing with longing for something I could not grasp and have longed for every day of my life.

More importantly, I learned that a great work of art can never be spent, it never stops meaning, retaining a core that outlives the circumstances of its creation, constantly changing while always staying the same.

The greatest thing about Heroes was that I didn’t understand it; I couldn’t enter it to appropriate it. It was never going to be about me. Which is why it never got boring and I’ve never stopped listening to it. It became a presence in my life, a radiant influence. Because of its strangeness, I’m now aware, I started formulating to myself what a great work of art is and could be. I began understanding that Heroes is one of the twentieth century’s masterpieces, and that “Heroes” is the greatest song of all time. More importantly, I learned that a great work of art can never be spent, it never stops meaning, retaining a core that outlives the circumstances of its creation, constantly changing while always staying the same. It took me years to arrive at all that, as I had to finish the urgent business of sorting out the sordid business of being myself. Nearly forty years later I must own up to the fact that what I strive for as an artist is creating something like Heroes — a thing of irreducible beauty and meaning. That might never happen, of course, but in 1977 David Bowie showed me the way and I followed. And I will always love him.

“I can remember/standing by the wall./ And the guards /shot above our heads./ And we kissed/ so nothing could fall.

And the shame was on the other side./Oh we can beat them/Forever and ever/Then we could be heroes/just for one day.”

Porochista Khakpour, author of The Last Illusion and Sons and Other Flammable Objects

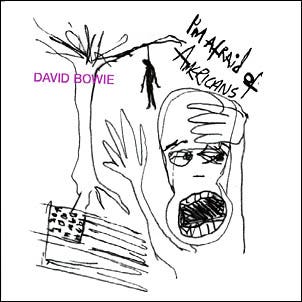

“I’m Afraid of Americans” — David Bowie remixed by Nine Inch Nails (1997)

It is impossible for me to pick a favorite David Bowie album but it was probably Diamond Dogs. And I love nearly all his songs (hits and misses, all), but the first music video I saw, in 1983, was his “Let’s Dance” so that remains very cherished. We somehow had illegal cable and much of my English-language skills came from watching MTV or The Twilight Zone. I still believe my often-bizarre fashion sense came from my introduction to American culture: Bowie, Boy George, Pat Benatar, Prince, and Cyndi Lauper.

But that’s not on my mind right now, those are not the songs I’m playing. When I was writing my second novel years ago, I kept going back to a song of his I encountered in college: “I’m Afraid of Americans.” It’s the anti-“Young Americans,” that sexy, glam-rock plastic-soul anthem I also love and ended up listening to far more in my lifetime. I don’t know how I first encountered “I’m Afraid of Americans” — it didn’t get as much radio play, as far as I can recall, and I’m just now reading that a rough cut was on the 1995 Showgirls soundtrack! (I remember it as the penultimate track on his 1997 album Earthling, which I loved and which many people I know loved less). Trent Reznor’s remix of the song, which was co-written by Bowie and Brian Eno, is the one I’m thinking of — and of course, the video.

I don’t know the first time, but I do know I heard it many times at certain NYC clubs, not one of those big ones but one of those sorta-lounges and kinda-bars you’d find in the East Village, their real last gasp in the neighborhood. In my head it plays on loop in one of those spots. The production, all industrial and electronic and so very NIN — dangerous and weird as everything felt in those final years of the last millennium, before the world became actually dangerous and weird.

The State of the Union is on livestream as I write this, and in my head I think to this video: the trigger-hands, my god, the trigger-hands.

I saw the video during some break from college, those final years of MTV actually being music television. In it Reznor — an old crush of mine and I think every misfit Nineties youth — is a cab driver named Jonny who is pursuing Bowie on the streets of New York, the streets of New York as I very much remember them in the late 90s — several degrees dirtier and grittier than now (but not as bad as they had been just before, everyone always reminded me). Bowie is running frantically and everywhere he turns there are New Yorkers amid some sort of altercation: couples, friends, strangers, and the one thing they have in common is their hands in finger-gun pose. It’s a chase movie and at the end there is a standoff, and watching this today its paranoia and intensity and anxiety feels so accurate. The State of the Union is on livestream as I write this, and in my head I think to this video: the trigger-hands, my god, the trigger-hands.

We think so often of Bowie as the man who loved everyone and embraced everyone. But we also sometimes mistakenly might think that means no fear, no suspicion, no desire for change. In the 1983 MTV interview with Mark Goodman, where Bowie holds MTV to task for ignoring black musicians, you see discomfort and even rage behind his mostly cool exterior. Nobody’s congeniality could be more intense. His positivity was never cheap, easy, for show. It was proactive and hopeful, it had the imagination to carve out a place if the place wasn’t there. The performative part came from someone who had had a hard life and knew others with hard lives; it came from someone who wanted so much more than this world, that the idea of boundaries, nations, states, seemed ludicrous.

I’m afraid of Americans I’m afraid of the world, belted Bowie, who one could say was always ahead of his time, though more precisely of no time in particular. But in this song, he is in this moment right now, at my side, this very moment of ours. In 1997, I was still four years from becoming an American — and the world still fours years from 9/11 — and back then I would never have dared say I was afraid of Americans. Today, I’m still afraid to say it; today, I’m still afraid of Americans sometimes. The one line I never quite understood, but I’m scared I do understand a bit now is maybe the saddest line in all of Bowie’s discography for me — God is an American, Bowie deadpans toward the end, and again, God is an American.

J. Robert Lennon, editor of Okey-Panky, author of See You in Paradise and Familiar, among others

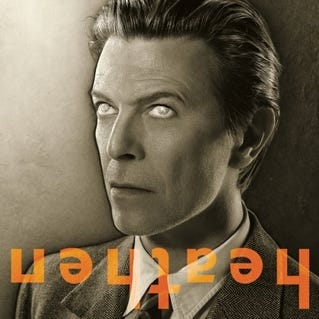

“Cactus” — David Bowie cover of The Pixies (2002)

I love all the Bowies. I was born the year of The Man Who Sold the World, formed my first band the year of Let’s Dance, and in between, rarely a day passed when I didn’t hear his music. I knew all the lyrics to every hit and turned the radio up whenever they came on. And yet I didn’t own a David Bowie record until 2002. In retrospect this seems insane. He was unequivocally one of my favorite recording artists, but I think there was something about his career — its breadth and drama, its explorations in style, gender, and sexuality — that frightened and intimidated me. By the time I got serious about playing rock music, as a fully flannelled and Adidas’ed cisgender indie rocker, Bowie seemed like a quaint nostalgia act.

Bowie wasn’t the past, and the Pixies weren’t the present; we’re all alive together and everybody is listening to everything.

Then I read a review of the then-new one, Heathen, and bought it on impulse. It’s a good record, but the thing that struck me was Bowie’s cover of The Pixies’ “Cactus.” The second I heard him singing it, I thought, “Oh, yeah, the Pixies’ version must be a cover.” Then I looked at the liner notes. Bowie really had recorded and released a cover of a Black Francis song. And suddenly the whole history of rock and roll came into focus for me: Bowie wasn’t the past, and the Pixies weren’t the present; we’re all alive together and everybody is listening to everything. Bowie was covering the Pixies because he loved the Pixies, as I did. And the Pixies, of course, couldn’t have existed without Bowie. “Cactus” is a completely demented song, a weirdly puerile riff on sex and death, and Bowie sings it as though he wrote it: “I miss your soup and I miss your bread / And a letter in your writing doesn’t mean you’re not dead / So spill your breakfast and drip your wine / Just wear that dress when you’re dying.”

This is an embarrassing epiphany for a 32-year-old musician to make: that all good music is in dialogue with other good music, that genre and subgenre are meaningless, and a real professional acknowledges not only his influences, but the accomplishments of his descendents. It’s a revelation that has carried over into my literary life, too: only a fool rejects the pleasures of the world that has arrived to replace him, and only the most cynical old dog declines to learn new tricks.

Ru Freeman, activist and author of On Sal Mal Lane and A Disobedient Girl

Hero

You listen, and though you feel everything has already passed you by, and your head is all tangled up, the singer calls you “love,” and you are not alone.

You don’t care that the music you hear has taken years to reach your country. You are a teenager, lying on the cold cement floor of a room in Colombo, Sri Lanka, listening through borrowed headphones to one of the few bootlegged cassette tapes you own: Top Ten Hits from David Bowie. You come from a culture comfortable with androgyny so you stare up at a poster of the skinny blonde boy that covers the cracks in your walls, and feel your heart melt; you think he can do no wrong while wearing lipstick, bellbottoms, and blue eyeshadow. You listen, and though you feel everything has already passed you by, and your head is all tangled up, the singer calls you “love,” and you are not alone. When the one music-show, “Pops in Germany,” that runs on the TVs the Japanese gifted your country, the one that plays the anti-war anthem, “99 Luftballons,” from the German band, Nena, every single week, adds Bowie and Jagger “Dancing in the Street” on repeat during and after Live Aid, you believe you’ve melded the family gift of understanding the link between capitalism and global poverty before you could walk, with your private satanic heart that loves pop music and all things American. You don’t have enough fabric to stitch yourself a cheetah print jumpsuit but you make do with a mini dress that hugs your boy-girl body as you dance. You listen to “Five Years,” and you believe your poster-boy made room in his head for “all the somebody people,” which means he must have made room for you. You imagine that when he sings about how he “touched the very soul/ of holding each and every life,” at the kind of free festival you have no hope of ever attending, that he was holding you, even though you know that all the joy was imagined, was just a claim you wanted to make the same way he did. You can’t afford the albums, but the tracks find you somehow and when the Berlin Wall comes down, even though your family has made sure you know how to pronounce Gorbachev and Perestroika, you believe much more in the idea of East Berliners gathering on the hard side of a wall to listen to Bowie serenade them. Time passes and different songs claim you, set your history to music. You grow up enough to become familiar with other walls from Arizona to Palestine, to hear guns above your head. And yet. You still believe that walls can be torn down by the strength of sweet voices singing love songs and reciting poetry. You know now that he believed singing to people he could not see moved him deeply and that he did not expect to be able to repeat the experience. You shrug and think that doing one brave and beautiful thing should be enough for any artist. You are sitting in a country far from the place where you were born, wrapped in a blanket and looking out on waters from the Pacific, thinking about compassion and literature, when you hear the news. You close your eyes and turn on “Rock ’N Roll Suicide,” all quiet in the inside of your head. You imagine hands reaching all the way across the world. Gimme your hands, you say, gimme your hands ’cause you’re wonderful.

Tanwi Nandini Islam, author of Bright Lines

“Under Pressure” — David Bowie and Freddie Mercury (1982)

This past year, I heard the a cappella version — a haunting experience — like remembering your past without any illusions.

“Under Pressure” — It’s technically a Queen song, one in which Freddie Mercury and David Bowie blew my heart open as a teenager, when I was discovering their music. Sonically, it’s a bridge between the rock ballads of the 70s and the pop harmonies of the 80s, in one riotous duet. Bowie’s refrain, It’s the terror of knowing what this world is about, watching some good friends screaming “Let me out!” moved me in a way I hadn’t really felt in music outside of the R&B and hip-hop I listened to. His voice grounds Mercury’s operatic yearning and desperation. What was incredible about David Bowie is that he appealed to everyone; our allegiance to our favorite music was broken when it came to him. I’m drawn to tension in music, and “Under Pressure” embodies the discord between Bowie and Mercury. It’s evident throughout the tune — the artists argued over the final mix — but the moments of harmony reveal two sides of the same genius both artists possessed. There is harmony, despite their differences. They bent convention in beautiful contortions, spanning a variety of genre, style, gender presentations, and this song manifests that. This past year, I heard the a cappella version — a haunting experience — like remembering your past without any illusions.

Amber Sparks, author of forthcoming The Unfinished World and Other Stories

Outside (1995)

Even just the name of the album resonated: I was outside, we were all outside, you know?

Outside is not my favorite Bowie album, but it came into my life at exactly the right time — one of those instances of art finding you when you need it most. I was in high school when it came out, and I was just starting to make art the way I wanted to make it, and was getting a lot of pushback for that, for being weird, and dark. Then came Outside. It was menacing, it was extremely dark, it was unsettling, and it was lovely and bizarre and completely new. I knew who David Bowie was, of course, but just his Top 40 stuff, Labyrinth, etc. I went out and bought a bunch of his CDs and I rented The Man Who Fell to Earth and I listened to Outside over and over and over again. And it just all clicked — I felt that HERE was a refuge for me, for people like me. It saved me, that album; saved my impulse to make art. It saved me as an outsider kid. Even just the name of the album resonated: I was outside, we were all outside, you know? I dug my old journals out the other day, in fact, because I remembered writing about Bowie. And yes, during that intense young joyful period of discovering David Bowie, I wrote this: “I think there are two kinds of people: those who like David Bowie and those who don’t get David Bowie. For me, when I listen to his CDs, I feel like there are other people on this planet who also feel like aliens, who feel like we come from somewhere else. I think we see the world differently, and feel apart from it. But I think we also see things that are ugly/beautiful about it. We see how tiny we are and how insignificant and how big and unknowable, and yes, scary, this strange place we’ve landed in truly is. It’s weird because you would think that would make you feel so very much alone. But listening to David Bowie’s albums, and feeling like a beautiful alien, makes me less lonely. I would like to meet more people who feel like beautiful aliens.”

Rob Spillman, editor and co-founder of Tin House, author of forthcoming All Tomorrow’s Parties (Grove Press, April 2016)

Christiane F. — Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo Original Soundtrack (1981)

Moody, dark, yet hopeful, the record perfectly captures how I feel about Berlin, the city I spent my first ten years in.

The deeply bleak 1981 movie about a teenage junkie in Berlin, based on the nonfiction Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo (We Children of Bahnhof Zoo), featured a soundtrack by Bowie, and included many of his greatest Berlin recordings with Brian Eno — “Heroes”, “Look Back in Anger”, “Warszawa” — as well as raw, intimate concert footage of Bowie in his Berlin prime. In the movie, no matter how low Christiane goes, she won’t give up her Bowie records, until she finally is so strung out that she sells them, a scene which devastated me like few have since. Moody, dark, yet hopeful, the record perfectly captures how I feel about Berlin, the city I spent my first ten years in. That he would next adopt my home city — New York — further solidified my love and personal connection to Bowie, a love connection held by millions, but which to me felt singular and real.

Marie-Helene Bertino, author of 2 A.M. at the Cat’s Pajamas and Safe as Houses

“Heroes” (1977)

Unlike rock bands who can hide among their number, when David Bowie took the stage, he did so alone. All eyes on him. That he decided to place assumed personas between the audience and him makes sense to those of us who understand wanting to simultaneously shine and hide. Beautiful buffers. It’s no wonder that practitioners of the solitary art of writing palpably worship artists like him, Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan… It’s no wonder that when one dies we feel like part of us dies. I’m writing this for Bowie because when we lose Bob Dylan you won’t be able to find me.

The farther into the true self you go, the less like everyone else you look.

My husband and I eschewed traditional elements for our wedding last year, but we liked the idea of a first dance. A song that would express important information about our shared vision of the future. We chose David Bowie’s “Heroes,” that mid-tempo, erratic anthem about dolphins, loyalty, and the royal feeling of love. The information: life is weird, fun, fleeting, and sometimes involves marine life. The farther into the true self you go, the less like everyone else you look. David Bowie didn’t look like anyone else. I add my voice to the chorus of eccentric softies who suffer the profound loss of his death. His work gave us permission, elegance, inspiration. We owe him.

John Wray, author of Lowboy, Canaan’s Tongue, and The Right Hand of Sleep

“Sound & Vision” (1977)

…a kind of Virgil through all the zones of hell and paradise that he himself had ventured through…

Bowie was so many things — practically anything and everything that anyone ever projected onto the gaudy and spectacular and at the same time curiously blank canvas that he presented to the public — but to me he was above all a man who made great art out of his own fascination with the strange and seemingly pointless human enterprise of art-making, and willingly served the rest of us as a kind of Virgil through all the zones of hell and paradise that he himself had ventured through. For this reason and many others he was an elder statesman to everyone who came after him, and even to his contemporaries to some degree, simply by virtue of his virtuosity; but he took great pains to disclose himself to us, time and again — even unto the very last video for the very last album — as a frustrated, tormented, fallible striver. He never lapsed into complacency and irrelevance precisely because he refused, as a fundamental artistic principle, to fully acknowledge his success. One of the reasons he was forever open to the latest developments in both pop and the avant-garde was that he managed to convince himself, over and over again, that failure waited just around the corner. But at the same time he could sing about the transporting joys of creativity with a sweetness and an effortless authority.

I challenge anyone, creatively inclined or not, to listen to the song Sound & Vision, for example, without pining for the artist’s life, with all its highs and lows. It can’t be done.