Interviews

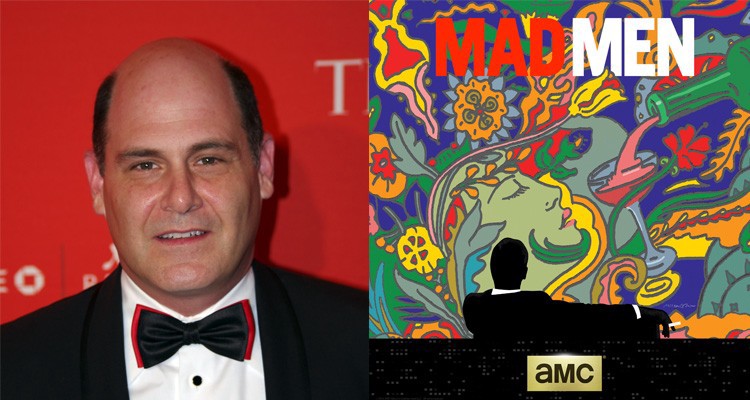

Cutting Past the Quick, an interview with Daniel Torday, author of The Last Flight of Poxl West

The title character in Daniel Torday’s new novel — The Last Flight of Poxl West — is a consummate storyteller. We meet Poxl West with a swift strike of charisma. He’s a former RAF pilot, a war hero, a best-selling memoirist, beloved uncle of Eli, art enthusiast…and not all that he seems. Torday is a consummate storyteller, too, though one of more integrity and honesty than Poxl. I sat down with him to hear some of his great stories and ideas over email. His novel is a moving inquiry into the limitations and possibilities of stories, how they have the power to shape, crush, reinvent us. In conversation, he is an endless fountain of pertinent quotations and insights, but perhaps the best insights he delivered were the ones that were all his own.

Early in the book, during a heated conversation with his girlfriend, Poxl feels he has maybe dawned on a working definition of love: “to disagree but to stay around and find out why, so it is no longer a disagreement.” This is perhaps also a reason for reading, for sitting with a novel until its conclusion. The Last Flight of Poxl West is an argument I wasn’t able to leave until the final page, and perhaps one I still haven’t left.

Hilary Leichter: The idea of muscle-memory is a recurring theme in your book: muscle-memory in learning how to play an instrument, in learning how to love, in our reactions and actions and our very human mistakes. Is there a kind of muscle-memory that goes along with writing a novel?

Daniel Torday: In moments of retrospection after a book comes out, probably it can’t hurt to acknowledge one’s mentors. So the oddly proper-nouny answer to this question is: George Saunders. I left a good job at Esquire Magazine to head up to the Syracuse MFA program, where I hoped to sit at George’s foot. He gives a lot of revelatory thought to process: just thinking deliberately about how we go about a fiction — what the regimen looks like of getting from not-writing to writing. It’s not mysterious, or precious — often it’s just finding the time, making the time when there is none, to work the sentences over and over and over until they all relate to each other. Flannery O’Connor has this great thing where she says something like “art is reason in making” — I think about that all the time. I take it to mean something like, a story or novel becomes artful, attains to a work of art, when every sentence, every move, style, is guided by the same central intelligence. Has its own DNA. That’s not something you achieve through your conscious mind. It’s a big-time subconscious-mind activity, and I think about that idea of muscle memory as another way of saying: find a way to let your subconscious mind, which is smarter and wiser, do as much of the work as possible. All of it, even.

HL: I love the idea of a book having its own DNA. If you could get it into a lab for analysis — I’m picturing bookish mad scientists armed with microscopes, getting paper cuts, etc. — what would the genome for POXL WEST look like?

DT: I love that idea of a book’s DNA, too! I stole it from Conrad, who says something like, “a work that aspires, however humbly, to the condition of art, must carry its own justification in every line.” I’ve always taken that to mean something like, a complete book has DNA that runs through every sentence. So I guess if they brought the POXL bloodwork into the lab they’d be surprised to find two interdependent organisms: Eli, who narrates from the present, and Poxl, who narrates through his memoir. But they’d also find that their DNA was closer to identical than they suspected. For me any first-person narrative that’s not told in the present tense derives its power, meaning, from this kind of coy fact of retrospection: what’s the chronological distance from the events to the moment of telling? Why is the narrator telling us now — what’s the occasion of the telling? And to return to Conrad, it’s in the sentences that we find that depth. As fiction writers, we’re always working at that perfect little long-evolved technology, the sentence.

HL: A book with two strands of DNA, like a chimera of sorts! There is an incredible momentum derived from the friction between Eli’s narration and Poxl’s narration, and from the alignment of their stories. How did your book split into these two distinct voices? Did it always exist in that form, or did it break by necessity, perhaps to provide occasion for the telling of the story? Was one voice easier to write than the other?

DT: The development of the two narrative strands here was odd and organic and jaunty, but in some crazy way natural. For years I had Poxl’s memoir, with a brief introduction from another young nephew-figure for Poxl. But it never really worked. At some point very late in the game I tried a short-story version of Eli’s narrative — and only after letting it sit for a year did I try to combine them. I was deeply skeptical that it would work. But I showed it to some of my most trusted readers — Rebecca Curtis, who has got to be working at a higher level than virtually any short story writer out there; Adam Levin, who always gives it to me straight — and they were surprisingly positive about it. And I’m not sure one voice was easier than the other. They each presented their own challenges — Poxl’s in all the homework it took to get there, Eli’s in just really wanting to get down the layers of that retrospective voice. What was harder was just getting the balance between the two in quantity and pace. By chance there’s actually just a lot more of Poxl than there is of Eli, though in some ways the story Eli is telling is the larger story of the novel itself. That was where Adam and Becky and a couple other late readers were so helpful — just in calling balls and strikes on whether the balance between the two worked.

HL: It seems that to properly imagine these events, specifically the events of Poxl’s World War II memoir, Skylock, you’ve had to do an incredible amount of research. Can you talk a bit about your process? Where did you start?

DT: Philip Roth has this great thing where he says the way to handle research is to not do it at all — at least in a first draft. When you’re getting the draft down, you just go. I mean, even if you knew not one thing of 1940’s London, you could start narrating, “As Preston Liverfootington walked down the, uh, cobbled (?) streets, he planned to spend his…uh…not-dollars…on a Pimm’s cup.” It’s awful, I know, but I mean only to say it’s not that you can’t get the prose down. That you can always do. Reading back that actually sounds like a not-bad start to a Barthelme story, a story with different aesthetic goals and told in a different context — you just have a lot of work to do, and some choices to make. So for me it was about getting drafts down where what mattered was Poxl’s emotional life — and then to go back in and expand. The things that helped most later were three-fold: the first was just going to retrace Poxl’s steps in Europe. I remember one early trip to Prague I just made a ton of notes about what I saw, and then on my next trip there, I checked what I’d written in Poxl’s voice against it. I was shocked by how little I had to change. Weirdly in a novel, it’s way more about not getting things wrong than it is about getting things ostentatiously right. That might matter in a nonfiction, but not so much in a novel. It can get showy.

The two main book sources for me were self-published memoirs, and really minute specific military histories. The former helped in getting so much of the dailiness down on the page — the details of what life looked like. The latter were great in being able to understand a day or two, a single air raid like the one I picked over Hamburg, so I could feel what it would have been for Poxl day-to-day. Oh, and one of the most helpful books was just a collection of New Yorker Talk of the Town pieces, written throughout the Blitz, by their main London reporter at the time. Her name was Mollie Panter-Downes, and she was a terrific observer. Her details, the way she presented them in real time, were just so precise and vivid.

HL: The phrase “What you know, you know” pops up again and again in these pages. It’s feels like a way for these characters to explain themselves, forgive themselves, explicate their individual stories. It started to read like a broken refrain, an apology, or even a mantra. Maybe it stuck out because I have Colson Whitehead’s brilliant essay about “You do you” on the brain, where he delves into the idea of a word William Safire coined: the tautophrase. Haters gonna hate. It is what it is. What you know, you know: is this a good philosophy when writing fact or fiction, or something in between? Is it a kind of way of understanding the idea of truth in writing?

DT: Well this is a complicated one — that line, “What you know you know,” is Iago speaking, after his awful business of putting honey in Othello’s ear is over. The next thing he says is, “From this time forth I never will speak a word.” I haven’t read that Colson essay (though I love his work and now want to immediately!) but I love that: tautophrase. I guess in a way it is at the heart of the stories both Poxl and Eli are telling: they’re stories of trauma, of the way memory and need can skew events over time. In my mind both of these characters just have this kind of eternal ache over the events they’re recalling, and some part of them has to narrate, but some other part wishes they could just let the past be. And in a way it really is central to the idea of “narration” itself — not simply listing facts, events, but making causal connections. E.M. Forster says “the king died, the queen died” isn’t a narrative; “the kind died, the queen died of grief” is. So on some level that question of causation is what burdens Poxl most, in a complicated way. Iago, too. But Poxl’s hitting on that phrase of Iago’s and sticking with it surely has something to do with a conflict between narrating, or maybe being prompted to narrate, or simply staying mute. Narrative, or just making a list of events. And so isn’t narrative in a way the very move past tautology, its opposite? To imagine events have caused each other, and make meaning of it.

HL: Poxl has this beautiful education in the arts that happens very naturally over the course of the narrative. His mother introduces him to painting early in the book. His first love, Francoise, introduces him to music and her mandolin. And then he climbs into a cave in the English countryside to read Shakespeare, almost as if you have to go spelunking for the written word. Where do you go looking (or spelunking) for inspiration, for art? Is an education in the arts a kind of travelogue, by necessity?

DT: That’s a really beautiful and generous read of Poxl’s growth over his memoir, Hilary. Thank you for it. I hadn’t thought about it in those terms, exactly, but it sounds just right hearing it. In a way if there’s a central conflict in the novel, it’s just that: Poxl’s desire to have his life be about all those loves — of art, of books, of music, of the lovers he lost — but the trauma of war pushed him instead into all these flights. In a quieter way, Eli, too, who might have liked to have studied art history, but ended up a historian. But I’d also just say that I’m always thinking of the other arts as such a useful analog to writing. I was talking the other day to a student of mine who also happens to teach the viola da gamba at Juilliard (I have some insanely talented interesting students), and found myself saying that music is the least representative art — its own, non-verbal, non-visual, non-narrative art. And she looked at me kind of askance. And I realized: I don’t think that at all! This might sound like lunacy or sophistry, but I like reading about physics, what I can understand of it (which isn’t all that much). But somehow string theory can give us this whole new view on music: if the physical world itself is at root not solid, but a vibration like a string, then isn’t music the world trying to speak itself back to itself? And isn’t there a similar vibration in the best prose or poetry? Makes me think of this line from Stanley Kunitz I love that I’m sure I’ll bungle but it goes something like, “I want to write a line so clear you can see the world through it.”

HL: Wow, that’s an amazing quote about sentences, and about writing in general. So much of storytelling hinges on these vibrations, where the “world speaks itself back to itself.” The prose in your novel is at once urgent and luxurious, which I think adds up to equal something akin to nostalgia. Just a few questions ago, you called the sentence a “perfect little long-evolved technology.” What are your personal criteria for a beautiful sentences? How do you know when a sentence you’ve written is giving off just the right vibration?

DT: You’re so kind! I never know if the sentences are doing just what I want, but I know I ultimately care about the sentence above all else. In some real literal way it’s the only tool at the writer’s disposal. Sometimes I think the perfect modern sentence is all about cutting past the quick — cutting almost to the point of incomprehensibility, or even a good bit past it. There’s a way that a sentence that risks almost not even making sense on its own invites the reader to have to fill in the gaps. It becomes an invitation rather than a foreboding. Or to stick with the initial metaphor, to staunch the bleeding after breaching the quick.

I’m a huge fan of Isaac Babel and the writers I think of as being somehow directly influenced by him — Leonard Michaels, Tobias Wolff, Amy Hempel, Denis Johnson, Saunders — and he was the great 20th century influence on cutting the line as bare as it can get. My process is pretty direct: in draft, I let myself go as freely as possible. But then on two or three or sixty-eight final rounds, I just go through with a pen and cut literally every word I’m able to while maintaining comprehensibility. I have a weird little rule, for example, where I’m not allowed to keep the words “that” or “and,” which often bloat my early-draft sentences. Lots of ands can help me get through a page, but the reader sure doesn’t need to know. Stuff like that — arbitrary, but little tricks to rub the strings down until they’re shining like new, ready to buzz.

HL: Eli’s passionate defense and promotion of Poxl’s memoir is one of the most touching parts of your novel. I was reminded of that possessive and exuberant way I often feel after discovering a new favorite book, or musician, or television show. There’s a frenetic desire to at once talk about the art in question with everyone and anyone who will listen, and a counter-desire to keep and save it all for myself. Have you ever felt this way about a writer or a book?

DT: All the time! It’s what I read for. I think that for a minute in my 20’s I might have wanted to be a critic, and being an undergraduate led me to have a kind of critical facility that could at times hinder the creative impulse. I mean, I know when something’s not working, but as a novelist it’s important not to mistake some aspect of a book not working as the whole thing being in trouble. The novelist’s job is to write until she encounters problems — real, seemingly insoluble problems — and then to figure out how to surmount them. That’s when the reader stands up and applauds — “Wow, I didn’t think she’d be able to hit that mogul and still keep on her skis, but phew! She landed with utter grace.”

Using cinema as an analog to writing can be insidious, but the first artist who comes to mind with this question for me is Wes Anderson. I suppose if you really start to try to push on a film like Moonrise Kingdom or The Grand Budapest Hotel you could come up with all kinds of criticism. Maybe you’d even have a point. But I find watching them to be an experience of almost unadulterated joy, and I don’t want the sophistry of criticism. I just want to be able to feel that joy. They’re perfect little hermetic objects, like Joseph Cornell boxes or Barry Hannah stories. With Anderson, my feeling is, if I can walk out of the theater for two days feeling everything I see is somehow purple, and my whole visual palette has changed, and inexplicably there’s an emotional element to that visual experience, why do I need to question it? I feel the same when I read, say, a Harold Brodkey story, or one by Karen Russell, or a Henry Green novel, or Fitzgerald, Roth, Bellow, Edward P. Jones, Nabokov, Deborah Eisenberg…the list could go on forever.

HL: Very early in the novel, Poxl recounts a story about helping his neighbors manage their father’s estate. He tells a mesmerized Eli about discovering a bookcase full of this man’s books, and each book is stuffed with a hundred dollar bill, his life’s savings invested in literature. They open the books and hundred dollar bills are fluttering to the floor. There is something comedic about this sequence — “There’s always money in the banana stand,” a la Arrested Development — but it was also one of the most moving images I’ve read in recent memory. It has a childlike magic to it, and an overwhelming sadness, or wonder, or maybe both? Can you talk a bit about how you came upon this story, which comes to feel central to the novel in so many ways? Are your books secretly stuffed with money, Dan? And what is the strangest thing you’ve ever found inside a book, aside from the content of the book itself?

DT: This was a weird one. The anecdote that set it off was one that my great aunt in Boston, my grandmother’s sister, told once. I’d spent so much time using my father’s East European family as models for this book, I consciously thought at some point, What stories am I neglecting on my mother’s side? And I remembered this story my aunt Ces had told. I was worried it would feel too shopworn, so I asked around about it, and no one else in the family seemed to remember it. Her neighbor wasn’t a writer, but apparently had just always used $20 bills as bookmarks, and after she died, her kids found thousands of dollars in her books. That’s the kind of story that when you’re a writer, once you hear it, I think you have no choice but to store it in some subconscious file for later use. (It’s also maybe an inversion of that epic scene in Gatsby when Owl Eyes is so amazed that Gatsby’s books are real, not just spines with no books).

As for me, I mostly just find coffee stains in my books. Though I can’t help but think here of that moment in one of my favorite novels, Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping, when Ruth and her sister find their grandfather’s pressed flowers filling the pages of his encyclopedia. Those dried flowers are almost secular relics — no, they are relics — the closest Ruth comes to physically touching her grandfather, who has died tragically before she was born, in the whole book. Isn’t that just a perfect little metaphor? Our memories pressed so cleanly between the pages of a book they can let us physically touch the remnants of our dead. Sounds a little like the whole gambit, doesn’t it?