essays

Dirty Life and Times: The Past, Present and Future of Working-Class Literature

by Adam Fleming Petty

Some of the most impassioned conversation in the literary world has been devoted to highlighting what it lacks: voices of people of color, of gays and lesbians, of those marginalized or oppressed or simply ignored. Look a little closer, however, and you’ll notice this conversation focuses on race and gender while paying less attention to a demographic category that’s arguably just as determinative: class. When calls are made for greater diversity in publishing, the economic backgrounds of authors or editors rarely get mentioned.

Recently, several writers have been trying to thread the topic of class into the ongoing discussion of representation and opportunity in the literary sphere. Lorraine Berry and Andrea Bennett, writing for Literary Hub and Hazlitt, respectively, offered accounts of how lower-class experiences tend to generate less interest from editors and reviewers. Berry writes:

But very little has been explicitly articulated about the exclusion of the great American underclass, that perpetually poor group on the bottom tier of society that includes all races/genders/creeds. And as we winnow out opportunities for art about poverty, we lose so much potential for change.

In The New Republic, Phoebe Maltz Bovy took an idiosyncratic approach to the issue raised by Berry and Bennett, speculating on why, exactly, readers of all sorts may not feel compelled to give their attention to the experiences of the lower classes. Bovy refers to reading fiction as “aspirational,” meaning readers pick up novels or short stories (but mostly novels, if we’re being frank) to imagine themselves as better or at least more interesting than they are in their everyday lives. And when it comes to writing about the working class, that’s where things get rough:

It seems to me that socioeconomic class is a tougher sort of diversity to bring to writing. Unlike the other varieties, it’s at odds with what readers are used to and what they’re likely to want — namely wealthier, more glamorous, or just less drudgery-having versions of themselves.

It seems to me that socioeconomic class is a tougher sort of diversity to bring to writing.

As a diagnosis of current literary tastes, this is, I think, more or less accurate. But the thing about tastes is they change. There was a period, not too long ago, where writing about decidedly un-wealthy characters going about their vehemently non-glamorous lives commanded the attention of both critics and readers. By looking at that period and its literature, perhaps we can gain a better perspective on our own.

***

Beginning in the mid-70s and continuing through the 80s, a loose group of writers, variously known as “dirty realists” or “literary minimalists” or, my personal favorite, “Kmart realists,” produced a sizable literature of lower-middle-class and working-class life. Raymond Carver remains the best known writer from this era, but at the time, there were several writers whose reputations were nearly equal to his, including Tobias Wolff, Jayne Anne Phillips and Bobbie Ann Mason. They mostly wrote stories, publishing them first in The New Yorker and other magazines, then gathering them into collections that landed on the front page of the New York Times Book Review. Retrospectively, it was the last time the short story could compete with the novel terms of critical and, perhaps more to the point, commercial attention. In an essay from the late 80s, David Foster Wallace surveyed the state of short fiction, finding it abundant and even lucrative:

The workshop phenomenon has been justly credited with the recent “renaissance of the American short story,” a renaissance heralded in the late seventies with the emergence of writers like the late Raymond Carver (taught at Syracuse), Jayne Anne Phillips (M.F.A. from Iowa), and the late Breece Pancake. More small magazines devoted to short literary fiction exist today than ever before, most of them sponsored by programs or edited and staffed by recent M.F.A.s. Short story collections, even by relative unknowns, are now halfway viable economically, and publishers have moved briskly to accommodate trend.

Short story collections? Halfway viable economically? Truly the 80s were a literary utopia!

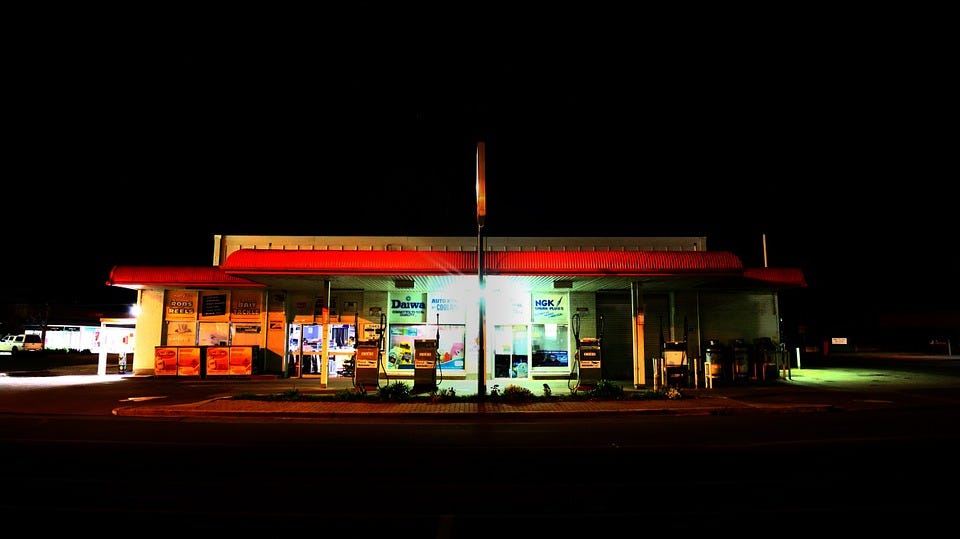

As a form, the short story collection is currently regarded as a kind of stepping stone, a way for young authors to clear their throats or midcareer authors to clear their hard drives. Of course there are exceptions, writers for whom the short story is the feature presentation — Lorrie Moore, say, or Kelly Link. But when Carver and others were at work, the short story collection had a sense of cohesion not unlike that of the album in popular music, to mention another form that’s seen better days. Why was the short story so central to the dirty realists? Carver once claimed that, in between working as a gas-station attendant and taking his two kids to the laundromat, writing short stories was all he had time for. Logistics aside, the short story soon became synonymous with depicting lower-class experience much the way that love is the preferred subject for the sonnet or the power ballad, and for critics, if not the dirty realists themselves, this constituted a turning away from the encyclopedic aims of the novel.

Logistics aside, the short story soon became synonymous with depicting lower-class experience much the way that love is the preferred subject for the sonnet or the power ballad…

The most succinct summation of dirty realism came not from a writer but an editor, and a British one at that. Bill Buford edited the highly regarded journal Granta for years, and in 1983 he devoted an entire issue to this new strain in American writing. Buford was the one who coined the term “dirty realism,” by the way; part of the movement’s appeal was that it lacked the braggadocio to call itself one, much less choose a name. Buford praised the realists for, among other things, doing away with the postmodern pyrotechnics of Pynchon and John Barth, honing their focus to stories and characters who wouldn’t recognize pretension if it came into the diner where they were pulling a late shift and ordered coffee. Buford wrote:

These are strange stories, unadorned, unfurnished, low-rent tragedies about people who watch day-time television, read cheap romances or listen to country-and-western music. They are waitresses in roadside cafes, cashiers in supermarkets, construction workers, secretaries and underemployed cowboys. They play bingo, eat cheeseburgers, hunt deer and stay in cheap hotels. They drink a lot and are often in trouble: for stealing a car, breaking a window, pickpocketing a wallet. They are from Kentucky or Alabama or Oregon, but mainly, they could just about be from anywhere: drifters in a world cluttered with junk food and the oppressive details of modern consumerism.

To use a contemporary term, the dirty realists were authentic. During a decade so greedy and fake it anointed Alex P. Keaton the voice of youthful rebellion, these quiet, uninflected stories about people lacking cultural sophistication seemed like an ideal antidote. Not quite a threat, however; the process of deindustrialization that began in the early 70s and was capped by Reagan’s deregulation of labor unions ensured this largely rural, largely white working class would never coalesce into a political constituency. Indeed, part of the appeal of dirty realism was how it let readers appreciate the authenticity of the lower classes without being asked to change it.

Dirty realism stayed prestigious and reasonably popular for about a dozen years, at which point maximalists like Tom Wolfe began voicing their displeasure with work of such modesty and calm. Not a bad run, as far as literary movements go. But it begs the question of why such work flourished then, and doesn’t now. We’ve had Kmart realism; why not Walmart realism?

Here’s where I make a sweeping generalization. During the dirty realist era, what made one “authentic” was lacking things. Those who didn’t have cable, who didn’t live in the suburbs, who didn’t have bachelor’s degrees, they were truly authentic, getting by on junk food and gas station coffee like monks living on bread crusts. Today, we become authentic by possessing things: the most organic, most fairly traded coffee, the craft beer brewed locally and served only in a single bar between the Fourth of July and Labor Day, the phone so smart it has achieved sentience and comes packaged with a certificate of authenticity like a piece of the true cross. Those without the means to purchase such talismans are inauthentic and bland, pumped full of toxins by the soulless food they consume like the subjects of a corporate research project.

Today, we become authentic by possessing things: the most organic, most fairly traded coffee, the craft beer brewed locally and served only in a single bar between the Fourth of July and Labor Day, the phone so smart it has achieved sentience and comes packaged with a certificate of authenticity like a piece of the true cross.

This is not to say there weren’t issues with the ways dirty realism was received at the time. Plenty of readers romanticized the stories of that era, finding a kind of savage nobility in the exploits of the underclass. I know when I first read those stories, I found all those janitors and addicts unimpeachably real, in touch with a truth I couldn’t access from my dorm room. But given the choice, I’ll take romanticization over demonization, for that is surely how the underclass is seen nowadays. Those poor people, with their guns and their religion and their inadequately progressive opinions, they’ll never make proper subjects for literature.

The contemporary writers who choose to depict the underclass tackle this sense of revulsion, often making it their subject. Take Lindsay Hunter, whose recent novel Ugly Girls is a gauntlet thrown at the feet of readers who’d prefer a little glamour and wealth. The titular characters are Perry and Baby Girl, high school students in name only, as they spend most of their time stealing cars, taking them for aimless rides, then ditching them in Walmart parking lots. The circumstances would fit right into a story by Carver or Phillips — Perry even lives in a trailer park — but the tone is entirely different. With the dirty realists, there was often a sense of settling, of coming to terms with one’s disappointments or failures or general insignificance. Perry and Baby Girl do no such thing. Getting left behind by the world has made them feral, craving stimulation and lashing out at those who get in their way. The story finds them evading a sex offender who insinuates himself into their lives through text messages, Facebook posts and cons played upon their families. (The swipe at Facebook is especially great, the pinnacle of Silicon Valley’s gee-whiz utopianism made into nothing other than a means of manipulation for white trash perverts.) Violence eventually boils over, splattering guilt on all concerned parties, the criminal and the disenfranchised taking revenge upon one another.

Hunter’s novel struck me as more than just a good story well-told. It seemed prophetic. As the rich get richer and the poor get cancer, Perry and Baby Girl seem less like cultural outliers and more like intimations of what’s to come. More and more population groups look to be slipping into various tiers of the underclass, artists and writers most certainly included. (Full disclosure: I’m writing this in a Walmart, killing time while my car’s oil gets changed.) Reading about the experiences of the underclass is more than a way of expanding one’s sense of sympathy. It’s a way of preparing for the future, fortifying oneself against coming storms.