Lit Mags

Don’t Bring Nightmares To the Breakfast Table

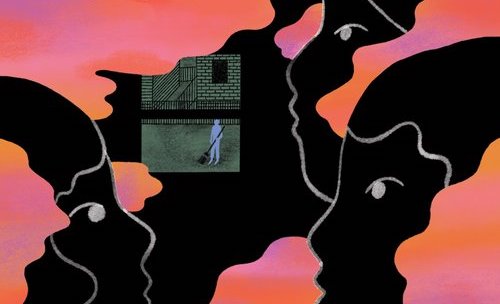

“The Breakfast” by Amparo Dávila is a story about the illusory line between nightmare and reality

AN INTRODUCTION BY AUDREY HARRIS AND MATTHEW GLEESON

Amparo Dávila, now 90 years old, is something of a lost-and-found figure in Mexico. From the 1950s to the 1970s she published delicate, moody poems and disturbing short stories that are written with precision and filled with nightmarish occurrences and unbalanced psyches. But then she sank from sight, hardly producing any new work after 1977. Only now is Mexico finally rediscovering her work and falling in love with it again.

Maybe this is part of why her stories seem to have a timeless quality — most of them speak to us from decades ago, but Dávila herself is still very much alive, and her edgy, uncanny work remains fresh. The august gatekeepers of Mexican literature praise her as a master, while young literary aficionados and darks (goths) who weren’t even born yet when she published most of her work line up eagerly for her autograph.

“The Breakfast,” originally published in 1961, is taken from The Houseguest and Other Stories — Dávila’s first full-length book to be published in English. In it we translated a selection of Dávila’s unsettling stories from throughout her career. Among them, “The Breakfast” is a characteristically dark shocker. But it also showcases two other qualities that Dávila is less famous for. One is her knack for using well-placed details and offhand glimpses to depict the social milieux of Mexico — in this case, the breakfast table of an upper-middle-class family in the capital. And the other is her dry, black sense of humor.

Like many of Dávila’s stories, “The Breakfast” is about the eruption of the chaotic, frightening things that roil beneath the controlled surface of everyday life. While she is always skilled at following the internal twists and turns of her characters’ minds, this particular story has a striking externality. It almost reads like a one-act play, told mainly through dialogue, movement, and gesture, with all the action taking place in a single room. It’s up to the reader to piece together what went on behind the scenes.

What is it that triggers Carmen’s outburst? Is it the frequent diets to maintain her figure that her mother frets about? The student protests on the streets of Mexico City and the Mexican government’s oppressive reprisals, which her father and brother bicker over? Her frenetic social life? Or is it the strange, repressed sexual relationship with Luciano that we catch distorted glimpses of? The hallucinatory dream scene at the heart of the story features a red carnation that forces Carmen to dance, like a contemporary version of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale “The Red Shoes” and the “wicked” girl they compel to dance. At the end of the Andersen tale, the girl must pay for her disobedience with death. When “The Breakfast” ends like an abrupt slap in the face, it’s clear that escape from the coercive forces taking charge of her body and mind will not be that simple for Carmen.

Audrey Harris and Matthew Gleeson

Translators

Don’t Bring Nightmares To the Breakfast Table

Amparo Davila

Share article

“The Breakfast”

by Amparo Dávila

When Carmen came down to breakfast at the family’s usual hour of seven thirty, she hadn’t dressed yet, but was wrapped in her navy-blue bathrobe with her hair in disarray. This wasn’t all that caught the attention of her parents and her brother, though; it was her haggard face, with hollows around the eyes, like the face of someone who’s had a bad night or is very ill. She said good morning in an automatic way and sat at the table, nearly col- lapsing into her chair.

“What happened to you?” her father asked, studying her carefully.

“What’s the matter, dear, are you sick?” asked her mother in turn, putting an arm around her shoulders.

“She looks like she didn’t get any sleep,” commented her brother.

She sat without responding, as if she hadn’t heard them. Her parents shared a glance out of the corner of their eyes, extremely puzzled by Carmen’s demeanor and appearance. Without daring to pose more questions, they began their breakfast, hoping that at some point she’d come back to herself. “She probably drank too much last night and what the poor girl’s got is a tremendous hangover,” thought her brother. “Those constant diets to maintain her figure must be affecting her,” her mother said to herself as she went to the kitchen for the coffee and scrambled eggs.

“Today I really will go to the barber, before lunch,” said the father.

“You’ve been trying to go for days now,” his wife remarked.

“But it’s such a pain just to think about it.”

“That’s why I never go,” the boy assured them.

“And now you have an impressive mane like an existentialist. I wouldn’t dare go out on the street like that,” said his father.

“You should see what a hit it is!” said the boy.

“What you should both do is go to the barber together,” suggested the mother, while serving their coffee and eggs.

Carmen placed her elbows on the table and rested her face between her hands.

“I had an awful dream,” she said in a small voice.

“A dream?” asked her mother.

“A dream’s no reason to act like that, sweetie,” said her father. “Come on, have breakfast.”

But she didn’t seem to have the slightest intention of doing so, remaining immobile and pensive.

“She woke up in a tragic mood, what can you do?” her brother explained with a grin. “These undiscovered actresses! But come on, don’t get upset, they can give you a part in the school theater…”

“Leave her alone,” said their mother, sounding annoyed. “You’re just going to make her feel worse.”

The boy didn’t press his jokes any further, and started talking about the rally the students had held the night before, which a group of riot police had broken up with tear gas.

“That’s exactly why I get so worried about you,” said their mother; “I’d give anything for you to stop going to those dangerous rallies. You never know how they’re going to end or who’s going to end up hurt, or who’ll get thrown in jail.”

“If it happens to you, nothing you can do about it,” said the boy. “But you’ll understand that a person can’t just sit calmly at home when other people are giving everything they’ve got in the struggle.”

“I don’t agree with the tactics the government is using,” said the father, spreading butter on a slice of toast and pouring himself another cup of coffee. “However, I don’t sympathize with the student rallies, because I think students should apply themselves simply to studying.”

“It would be hard for such a ‘conservative’ person like you to understand this kind of movement,” said the boy ironically.

“I am, and always have been, a supporter of liberty and justice,” his father replied, “but what I don’t agree with…”

“I dreamed that they killed Luciano.”

“What I don’t agree with…” the father repeated — “That they killed who?” he asked suddenly.

“Luciano.”

“But look, dear, to act like that over such a ridiculous dream, it’s as if I dreamed that I embezzled money at the bank and I got sick because of it,” said the father, cleaning his mustache with his napkin. “I’ve also dreamed many times that I won the lottery, and as you can see…”

“We all dream unpleasant things sometimes, and other times lovely things,” said the mother, “but none of them come true. If you want to read your dreams according to the way people interpret them, death or coffins mean long life or a prediction of marriage, and in two months…”

“And what about the time,” Carmen’s brother said to her, “that I dreamed I went on vacation to the mountains with Claudia Cardinale! We were already at the cabin and we were getting to the good part when you woke me up, remember how furious I was?”

“I don’t really remember how it began… But then we were in Luciano’s apartment. There were red carnations in a vase. I took one, the prettiest one, and I went to the mirror,” Carmen began recounting, in a slow, flat voice without inflection. “I started playing with the carnation. Its smell was too strong, I kept on inhaling it. There was music and I wanted to dance. I suddenly felt as happy as when I was a little girl and I would dance with Papá. I started dancing with the carnation in my hand, as if I were a lady from last century. I don’t remember how I was dressed… The music was lovely and I abandoned myself to it. I had never danced like that before. I took my shoes off and threw them out the window. The music went on and on, I started to feel exhausted and wanted to stop and rest. I couldn’t stop moving. The carnation was forcing me to keep dancing…”

“That doesn’t sound like an unpleasant dream to me,” her mother commented.

“Forget your dream already and eat some breakfast,” pleaded her father again.

“You’re not going to have time to get dressed and go to the office,” her mother admonished her.

As Carmen didn’t show the slightest sign of paying attention to what they said, her father made a gesture of discouragement.

“Saturday’s the dinner for don Julián, finally. I’ll have to send my Oxford suit to the dry cleaner, I think it needs a good ironing,” he said to his wife.

“I’ll send it today to make sure it’s ready for Saturday, sometimes they’re so unreliable.”

“Where’s the dinner going to be?” asked their son.

“We haven’t decided yet, but most likely it’ll be on the terrace of the Hotel Alameda.”

“How elegant!” the boy remarked. “You’ll love it,” he assured his mother. “It has a magnificent view.”

“I have no idea what I’m going to wear,” she complained.

“Your black dress looks great on you,” her husband said to her.

“But I always wear the same one, they’re going to think it’s the only one I have.”

“Wear a different one if you like, but that dress really does look good on you.”

“Luciano was happy watching me dance. He took an ivory pipe out of a leather box. Suddenly the music ended, and I couldn’t stop dancing. I tried again and again. I desperately wanted to fling away the carnation that was forcing me to keep dancing. My hand wouldn’t open. Then there was music again. Out of the walls, the roof, the floor, there came flutes, trumpets, clarinets, saxophones. It was a dizzying rhythm. A long rough shout, or a jubilant laugh. I felt dragged along by the beat, getting faster and wilder. I couldn’t stop dancing. The carnation had possessed me. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t stop dancing; the carnation had possessed me…”

The three waited a few moments for Carmen to continue; then they traded glances, communicating their puzzlement, and kept on eating breakfast.

“Pass me some more eggs,” the boy asked his mother, and he looked out of the corner of his eye at Carmen, who was sitting absorbed in herself, and thought: “Anyone would say she’s stoned.”

The woman served eggs to her son and picked up a glass of juice that was sitting in front of Carmen.

“Drink this tomato juice, hija, you’ll feel better,” she pleaded.

When she saw the glass her mother held out to her, Carmen’s face distorted completely.

“No, my God, no, no! That’s how his blood was — red, red, thick, sticky! No, no, how cruel, how cruel!” she said, violently spitting out the words. Then she hid her face in her hands and began to sob.

Her mother, distraught, stroked her head. “You’re sick, dear.”

“That’s right!” said her father, exasperated. “She works so much, she stays up every night, if it’s not the theater it’s the movies, dinners, get-togethers, and look, here’s what happens! They want to use it all up at once. You teach them moderation and it’s ‘you don’t know anything about it, when you were young everything was different’ — well, it’s true, there are lots of things you don’t know about, but at least you don’t end up…”

“What are you insinuating?” His wife’s voice was openly aggressive.

“Please,” their son butted in, “this is getting unbearable.”

“Luciano was lying on the green divan. He was smoking and laughing. The smoke veiled his face. All I heard was his laughter. He blew little rings with every mouthful of smoke. They went up, up, and then they burst, they broke into a thousand pieces. They were tiny beings made of glass: little horses, doves, deer, rabbits, owls, cats… The room filled with little glass animals. They settled all around, like a silent audience. Others hung in the air, as if they were on invisible cords. Luciano laughed and laughed when he saw the thousands of little animals he was puffing out with each mouthful of smoke. I kept dancing, unable to stop. I barely had space to move, the little animals were invading the room. The carnation was forcing me to dance, and more and more animals came out, more and more; there were even little glass animals on my head; they nested in my hair, which had become the branches of an enormous tree. Luciano roared with laughter like I’d never seen before. The instruments started to laugh too, the flutes and the trumpets, the clarinets, the saxophones, they all laughed when they saw I didn’t have room to dance, and more and more animals came out, more, more… A moment came when I could hardly move. I was just barely swaying back and forth. Then I couldn’t even do that. They had me completely surrounded. I looked miserably at the carnation that was demanding that I dance. There was no carnation anymore, there was no carnation — it was Luciano’s heart, red, hot, still beating in my hands!”

Her parents and brother looked at each other in confusion, not understanding anything now. Carmen’s disturbance had burst in on them like an intruder breaking the rhythm of their lives and throwing everything into disarray. They sat in abrupt silence, blank, fearful of entertaining an idea they didn’t want to consider.

“The best thing would be for her to lie down for a bit and take something for her nerves, otherwise we’ll all end up crazy,” said her brother finally.

“Yes, that’s what I was thinking,” said her father. “Give her one of those pills you take,” he ordered the mother.

“Come on, dear, go upstairs and lie down for a bit,” said her mother, overwhelmed, trying to help her daughter to her feet, though she herself lacked the strength to do anything. “Take these grapes.”

Carmen lifted her head; her face was a devastated field. In a barely audible murmur she said:

“That’s how Luciano’s eyes were. Static and green like frosted glass. The moon was coming in through the window. The cold light shone on his face. His green eyes were wide open, wide open. They were all gone now, the instruments and the little glass animals. They had all vanished. There wasn’t any more music. Just silence and emptiness. Luciano’s eyes stared at me, stared, as if they wanted to pierce through me. And I was there in the middle of the room with his heart beating in my hands, beating still… beating…”

“Take her upstairs to bed,” said the father to his wife. “I’m going to call the office and tell them she’s not feeling well, and I think I’ll call the doctor too.” And he searched for approval with his gaze.

Mother and son nodded yes while their eyes thanked the old man for carrying out their most immediate desire.

“Come on, dear, let’s go upstairs,” said Carmen’s mother.

But Carmen didn’t move, nor did she seem to hear.

“Leave her, I’ll bring her upstairs,” said her brother. “Make her some hot tea, it’ll do her good.”

The mother walked to the kitchen with heavy steps, as if the weight of many years had suddenly fallen upon her. Carmen’s brother tried to move her, and when she didn’t respond, not wanting to do violence to her, he decided to wait and see if she would react. He lit a cigarette and sat down next to her. Their father finished on the telephone and dropped into an old easy chair, observing Carmen from there. “Now no one’s gone to work today, hopefully it’s nothing serious.” The mother made noise in the kitchen, as though she were stumbling at every turn. The sun came in through the window from the garden, but it lent no warmth or cheer to that room in which everything had come to a standstill. Their thoughts and suspicions lay hidden or veiled by fear. Their anxiety and distress were shielded by a desolate silence.

The boy looked at his watch.

“It’s almost nine,” he said, just to say something.

“The doctor’s on his way; luckily he was still at home,” said the father.

“The Last Time I Saw Paris” began to play when nine o’clock struck on the musical clock they’d given to the mother on her last birthday. She came out of the kitchen with a cup of steaming tea, her eyes red.

“Go on upstairs,” her husband said to her. “We’ll bring her up.”

“Let’s go upstairs, Carmen.”

Father and brother lifted her to her feet. She made no resistance to being led, and slowly began to climb the stairs. She was very distant from herself and from the moment. Her eyes gazed fixedly toward some other place, some other time. She resembled a ghostly figure drifting between rocks. They didn’t make it to the top of the stairs. A pounding on the door to the street halted them. The brother ran downstairs, thinking it was the doctor. He opened the door and the police barged in.