Craft

“How Can They Write About Anything But Pain?”

Fazilhaq Hashimi on the writing life in Afghanistan

We’ve asked some of our favorite international authors to write about literary communities and cultures around the globe. We’re bringing you their essays in an Electric Literature series: The Writing Life Around the World. This month’s installment is by Fazilhaq Hashimi, an emerging writer from Afghanistan.

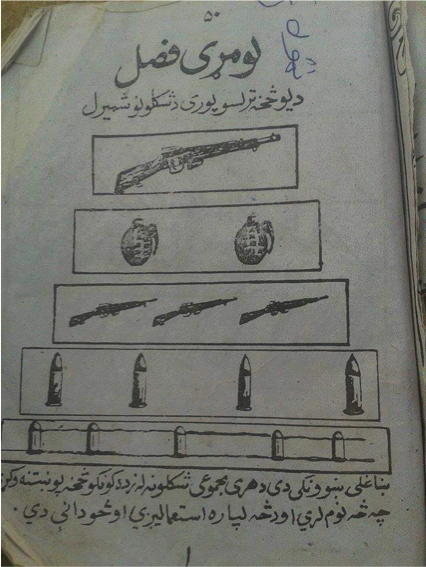

Here is a page from my elementary school math book from the Afghan civil war era (1992–2001). At the bottom of the page, the teacher’s guide notes that the instructor “must ask about the names, usage, and quantity of the above items.” The word “quantity” is the only math-related term. It is mentioned at the end of the series. The names and usages of the ammunitions are given pride of place. In language classes, while “A” was for “Allah”, the rest of the Dari or Pashtu alphabets included war-related components such as “T” for “Toopak” (gun), “Sh” for “Shamsheer” (sword), “J” for “Jihad,” “M” for “Mujahid,” and “Ta” for “Talib.” Every book promoted war, violence, and guns. Math problems were asked as, “A group of Mujahideen are on the frontline. Three of them are on duty at the checkpoint. Each has a box that consists of sixty bullets. In the fight against the infidels, the first Mujahid fired 24 bullets, the second 40, and the third 16. Write the total number of bullets fired and the numbers that are remaining.” Sometimes such questions were even expanded, “If a total of 19 infidels were killed with a single shot by the brave Mujahideen, how many bullets missed?”

That’s how Afghan children were taught in the refugee camps in Pakistan. The students who were left in Afghanistan were only taught religious subjects. All the scientific, extra-curricular, and art classes were erased from the curriculum. Literature and poetry, however, were not completely forgotten. Each morning, the students were lined up to read aloud a patriotic poem and to recite a religious Taraana (song). I remember the Taraana that was once sung by a student on the loudspeaker. Everyone praised him for his gifted talent as his soft voice echoed in the school,

“Oh, my Mujahid brother, I’m a Muslim,

Lying injured at the infidels’ prison.”

Though known as the “graveyard of empires,” lab mouse for various regimes, safe haven for terrorist groups and opium, Afghanistan is also the land of poetry, story-telling, fables, folktales, and proverbs. It’s the birthplace of Rumi, motherland of Avicenna, realm of Gul Pacha Ulfat, love-land of Rabia-e-Balkhi, empire of Mahmood Ghaznawi, and the land of Ahmad Shah Abdali, the founder of Afghanistan and a poet himself.

Until the early 19th century, many of the former rulers shared an intense interest in poetry. King Amanullah’s father-in-law, Mahmud Tarzi is known as the “Father of Afghan Journalism.” In October 1911, Tarzi founded Seraj-al-Akhbar, the first ever newspaper in Afghanistan, which published biweekly until January 1919. Tarzi and King Amanullah were modern thinkers who opposed religious extremism and worked for reforms and secularization until the government was overthrown by a coup in 1929. Tarzi fled to Turkey and resided there until he died in 1933. However, poetry still lives in and nourishes this country, much like its beautiful year-round perennial flowers. The Narinj Gul, or Orange Blossom, Poetry Festival in Jalalabad has been celebrated for more than 60 years now. In Kandahar, there is the Anar Gul, or Pomegranate Blossom, Poetry Festival. These annual traditions provide opportunities for writers and poets to recite their work in front of thousands of people from across Afghanistan. The writings reflect on love, peace, solidarity, youth, corruption, illiteracy, causalities, incompetent government, destruction and wiping out the seeds of hatred, discord, and disunity.

Avicenna, Ahmad Shah Abdali, Mahmud Tarzi, Rumi

Afghanistan’s literary foundation has been built on “oral literature,” except for the works of a few legendary writers. I come from a family where fables, proverbs, and stories were quoted regularly to convey messages. Now, my brother is a published Pashtu language poet and my younger sister writes in Dari. On the other hand, I write short stories in English. I believe we inherited the stimulus from our mother. She was uneducated — she could not write nor read with the exception of the Holy Quran and some other Duas (Islamic prayers) — but she was blessed with a miraculous art of storytelling. “It reminds me of this story…” was a familiar expression of hers. In 2010, when I was twenty years old, we lost her to cancer, but in all those years I don’t recall her repeating the same story or proverb except to emphasize the message or to bring out new meaning in a different context. She was raised with folktales too. Her mother told us of women using Tappa or Landay (two-line poems) to express anger, pain, and affection, young-lovers narrating a Naara to express a crush, grandmas telling Naakal or Qessa to put children to sleep, clergies delivering Moonajat to express devotion.

This still is the culture in many of the remote villages. Such stories have been transferred from generation to generation by word-of-mouth. Luckily, some writers and publishers, like Operation Mercy Afghanistan, Danish Publications Afghanistan, and Aksos Bookstore are now giving this oral literature a new life in print.

In Afghanistan, we do not write for fun, passion, or money but to express the immeasurable pain inside. Maybe that’s how the actual writing is. There must be something discomforting to be disclosed. At least, that’s how we see it. Rabia-e-Balkhi, probably one of the first female poets, was in love with a slave. Her brother, Hares did not approve of this. In the process of expressing her unbearable longing for Baktash, she started writing. She is said to have written her last poems with her blood in the bathroom she was locked in. A friend of mine is a writer and a social activist; he produces his best work after he has witnessed injustice, discrimination, or wrongdoing. It seems to be a common incentive among the contemporary Afghan writers — recent writings are filled with the pain, agony, and suffering of the Afghan people. That’s how my writing journey started too. My first story depicted the reality of a forced marriage. I write to portray cultural practices that are based on superstitions, norms, and traditions. When I re-read my own work, I find it melodramatic, more a Greek tragedy than a work of the 21st century. It can’t be helped. I feel like there is an inner voice reaching out to me, dragging me to write. The writing receives its inspiration from true stories around me. I hear the characters’ dialogues, find them haggling with salesmen, cursing the government, or striving to prevent a mischief. There are nights when I can’t fall asleep unless I first put my thoughts on paper. By the time I’m done with the story, some pages are wet-dried.

In a country where people are born and killed in wars and social disorders, how can they write about anything but pain?

Perhaps the last several decades of wars, the rise and fall of regimes, the shootings, and the lack of peace have killed our creativity. A friend of mine finds it hilarious to anonymously play a loud AK-47 shooting ringtone during the crowded Juma prayers or to shoot a glass building with a rocket launcher to see how the glass will shatter. One of my friend’s uncles, an elderly man, still keeps extra food and sacks of wheat in his basement out of fear that a fight may break out and for days no one will be able to go out. Our minds are distracted with the disturbances of wars. Afghans in the remote provinces still build their walls thick to prevent casualties in case of a rocket strike. In a country where people are born and killed in wars and social disorders, how can they write about anything but pain?

Since the beginning of the 19th century, over twenty different flags have been flown over Afghanistan by rulers, monarchs, kings, Emirs, and presidents. This also means that over twenty dissimilar political and social ideologies have been practiced. Each ruler exercised his own restrictions on the ways people lived, including freedom of speech and writing. The reason many rulers held strong interests in poetry was that poets were paid to flatter them and to praise their empires, castles, and armies. Anyone writing against the state was hanged, murdered, or exiled.

Self-censorship has ancient roots in Afghan history, though writers seem always to find a way to speak up. In the fables that our grandmother told us, the lion could be personified as the “cruel king”; the fox as the flattering clerk; the wolf as the wise minister; sheep, goats, and cows as the inhabitants. This can’t be done in the 21st century. Therefore, writers disguise themselves through pen names. It reminds me of this proverb, “As long as there’s a head, many hats can be worn.” It refers to the legend of a man who was threatened to death if he refused to give his beloved hat to the thief. He hesitated initially and then handed the hat to him and whispered, “If there’s life in my head, there will be many hats.”

Social activism and writing go hand-in-hand in Afghanistan.

There’s a saying, “Anything is possible in Afghanistan.” Journalists are regularly beaten, novelists can’t write freely, and newspapers are warned. Even though the eras of religious and communist extremism are gone, artists are commonly ill-treated and excoriated. According to the Afghanistan Journalists Center, 47 journalists, writers, and media workers have been killed or murdered since 1994; thirteen have been abducted and fifteen jailed. They are mostly Afghans. A few are expat journalists. The current Unity Government of Afghanistan is made up of both open- and closed-minded individuals. That’s probably another characteristic of post-conflict societies and ongoing war zones where the warlords are empowered to restore a temporary peace. Writing, reporting, or even posting against a single political figure, current or deceased, might put your life at risk. Such fears limit the writing capabilities of authors inside the country.

The high demand for writing about Afghanistan in the recent years has given birth to Afghan writers in exile or the so called foreign “experts on Afghanistan” that have too little understanding of the actual country and its culture. In addition, it is quite astonishing how the recent regimes self-censored themselves and the inhabitants. Communists strictly prohibited religious Islamic books and executed intellectuals who were considered threats to the government; following that, the Taliban regularly burned stacks of “non-Islamic” books in public places all over the country. The current government also seems to act blindly toward the accomplishments of many artists and sometimes even tries to censor them. Recently, the social activist and writer Masood Farzan was warned by a government official that his intentions, evident in Facebook posts and comments, were hostile to and aimed at overthrowing the current government. Masood responded, “If the government is that weak that it can be overthrown by my Facebook posts, let it be overthrown!”

Although Pashtu and Dari are the languages of love, poetry, literature, and proverbs, they are also the languages of wars, criminals, warlords, and human rights violators. Afghans are constantly the victims of their own languages and words. For instance, hundreds of Pashtuns were killed after they were unable to pronounce, “Qo-root,” a type of dried Afghan whey. They were asked to pronounce the word in order to differentiate them from other ethnicities, and when they could only say, “Koo-raat,” they were killed by having nails hammered into their heads. I learned how to say both words exactly the way they should be pronounced; many parents taught their children the same.

Language is a symbol of power in this part of the world.

Now, there are two other present-day words that have divided the country, including the Parliament, ministries, courts, and even academic institutions: Pohantoon and Danishgah. They both mean “university,” except the latter has a more Iranian root and emergence. Parliamentarians have fought over these words, undergraduate students have stabbed each other with knives, friends have become enemies, neighbors have turned into strangers, and classmates have grown into foes for opposing use of one of the other. Language is a symbol of power in this part of the world. When I tell my friends that my brother is a published Pashtu poet, some ask, “why not a Dari one?” I respond, “My sister writes in Dari.” To provide further justification, I add, “And I write in English. And I hope that one day; one of my siblings will become an Uzbek writer.”

I feel so relaxed writing in English. I do not think of ending up with a word that would conflict with the other national language of Afghanistan, nor will I anger my close friends. I was driven into writing when I started reading. I read my first English language book, For One More Day, by Mitch Albom, several times during the year I stayed with an American host family in Highlands Ranch, Colorado. I spent numerous hours in the Douglas County Library. Not having standard libraries in my own country, I was inclined to read as much as I could. Thus, libraries hosted me as much as my host family did.

It is very easy for writers to be labeled, “racist” or Kafir (infidel) in Afghanistan. Some of the most well-known current writers and social activists are Barry Salaam, Emal Pasarlay, Musa Zafar, Majeed Qarar, Masood Farzan, Lina Rozbeh, Shaista Sadat Lameh, Wais Barekzai, and Fahim Tokhi. Depending on their writings and statuses, they are branded as linguistic, ethnic, or tribalistic bigots; fascists, nationalists, xenophobes, xenophiles, atheists, or self-loathing Afghans.

It is hard to believe but there are still good writers who strongly support the harsh former regimes of the country, including the Taliban, the communists, and the interventionists from neighboring countries, but just like the residents of the country, the writers, too, are divided. They are as political as the government officials.

This leads to the question whether a writer is neutral or not. Maybe my mother was right when she quoted, “One’s own flaw is between the shoulders.” You can’t see it. The writers are probably blind to their flaws. Or maybe writing in Afghanistan is inherently biased. Even if you are an individual who does not take sides, your ethnicity, tribe, language, and peers will make you prejudiced. For instance, if one of the above writers regularly writes in one of the two national languages other than his/her own native language, the followers accuse him/her of not valuing the language.

Writing or reporting against a political figure might put your life at risk. Such fears limit the writing capabilities of authors inside the country.

Social activism and writing go hand-in-hand in Afghanistan. Afghan writers tend to circulate their works in bits and pieces over Facebook. Only a small number of writers have books of their own. This could be due to the lack of readership and publishing opportunities. When my brother and I were assessing various publishing companies for reprinting his collection of poems, we came across a number of bookstores that volunteered to sell newly printed books only if the writers provided the books to them free of cost. In a war-torn country like Afghanistan, there is little demand for books; people prefer to read short (at times biased and discriminatory) Facebook statuses and Twitter posts instead.

I have traveled a long path (of wars, poverty, and illiteracy) to writing, and so did many of my fellow Afghan writers. We will cling to it and do our best not to lose the opportunities we have. The culture of expressing our own point of view is nourishing. The number of both male and female writers is increasing. There’s also an active community of female writers, including the members of the Afghan Women’s Writing Project. Unfortunately, there are other groups of writers and social activists on the rise. When I read their work, I think of the schoolbooks from the civil war era. And yet their work is perhaps even more destructive and dangerous. The citizens of this country are provoked against each other by young writers who inject poisonous and prejudiced feelings into the minds of their own ethnic groups. They use their creativity in publishing discriminatory writing, posting racist videos, creating Facebook pages and closed groups slandering other ethnicities. At least, the civil war books asked for unity against a foreign force. These writers and social activists are dividing the country into pieces.

Maybe these writers are the products of those civil war books and education?

Or, are they producing another generation with far more destructive ideologies than their own?

About the Author

Fazilhaq Hashimi is an Afghan author writing in English. His work, including the short story, “If I Heard Her Right,” has been featured in The Gifts of the State, New Writing from Afghanistan (Dzanc Books) and Electric Literature. He studied at the American University of Afghanistan and recently relocated, along with his wife, to Colorado, where he is working on several new stories.

You can find all the essays from The Writing Life Around the World at Electric Literature.