Craft

“Howl” in Italian

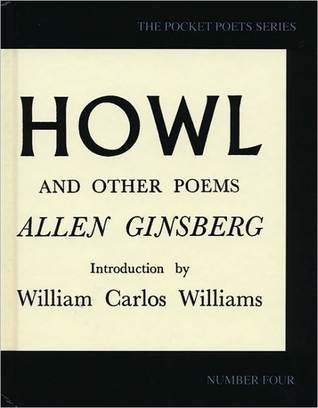

“Howl” was first translated into Italian by Fernanda Pivano, who at her funeral in 2009 was called “Signora America, signora libertà, signorina anarchia.” She became famous over the course of her life partly for translating Hemingway (with whom — as with Allen — she became a good friend), Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Kerouac, Burroughs, David Foster Wallace, and more. As one online commenter put it, “We grew up literally drinking her translations, before even trying to understand the nimble English jargon used by Allen, Jack and the others.”

But that is not method. That is the “who,” not the “how,” and certainly not the “Howl.” Pivano’s correspondence with Allen Ginsberg in relation to the poem’s translation is instructive. In their letters, Ginsburg answers Pivano’s questions about “Kaddish” and other poems, describing his mother’s “paranoiac complains … used as surreal fragments”; defining cultural references (“Woody Woodpecker is an allied cartoon character, hero of a series of cartoon disasters in technicolor”); explaining how “the LSD poem” was “written at Stanford’s Mental Health Experimental Lab and I’d asked the doctor to bring me various things to look at while under state of drug — Gertrude Stein on phonograph, some Wagner records.”

This is all part of the inquiry that French poet and translator Yves Bonnefoy identified as essential to capturing the spirit or essence of a work in translation: You don’t want your car to take you to the supermarket and back; you want it to sail from the woods to a farm to a city to a beach clogged with kites and back again. So it is with language.

“Howl,” of course, begins:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,

starving

hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking

for an angry

fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly

connection to the

starry dynamo in the machinery of night

“Urlo,” the title of “Howl” in Pivano’s Italian collection Jukebox All’Idrogeno (and it seems to be out of print, too), is a scream or a shout that seems almost thrown and begins:

Ho visto le migliori menti della mia generazione

distrutte dalla pazzia, affamate nude isteriche,

trascinarsi per strade dei negri all’alba in cerca di droga rabbiosa,

hipsters dal capo d’angelo ardenti per l’antico contatto celeste con la dinamo stellata nel macchinario della notte

A rough translation back into English would read:

I saw the best minds of my generation

destroyed by madness, starving naked hysterical,

dragging themselves at morning through the negro streets angrily looking for a fix,

hipsters from the head of an angel burning for the ancient paradisical contact with the starry dynamo in the machinery of night.

There are details here worth pointing out: the first is “pazzia,” as in “madness,” though it also means “a mad scene.” Then there is the question as to why “starving hysterical naked” become “starving naked hysterical”; does there need to be greater rhythmic emphasis placed on hysteria when the poem is called “Urlo?” There is “looking for an angry fix” approximated as “rabbiosa di droga,” being so hooked on drugs that you’re rabid for them. There is “dal capo d’angelo” or “from the head of an angel,” and one wonders if a silent, implied verb would be appropriate here, i.e., “Plucked from the head of an angel?” “Who emerge from the head of an angel?”

It should also be said that it’s nice to see “stellata” and “notte” play off each other so, even if notte doesn’t constitute the entirety of the line.

While writing this, I’ve stumbled across phrases like “hipster aureolati” or “hipsters dal corpo d’angelo” (from the body of an angel) while wondering why a phrase like “hipster con la testa di un angelo” or “hipster celeste” is somehow comparatively better or insufficient.

As a reader and a writer, my immediate impression is to say, “Yes! Yes!” to some of these phrases, especially with “hipster aureolati,” which I love, but I double-checked with Agnese Peretto, who did very well on the Italian literary-reality show Masterpiece — which I wrote briefly about here — and she told me that “Aureolati è una parola troppo difficile per un italiano normale” — that is to say, that ‘aureolati’ is a difficult word for the average Italian, and that it would be “meglio” to go with “con la testa di un angelo.”

Sometimes the language slows Ginsburg’s rollicking verse down (think of the changing nature of ‘santo’ with lines like “Tutto è santo! tutti sono santi! dappertutto è santo! tutti i giorni sono nell’eternità! Ognuno è un angelo!”), but sometimes Italian and “Howl” is a wonderful fit wonderfully done, especially when you read lines like, “Santa la soprannaturale ultrabrillante intelligente gentilezza dell’animo!” (Holy the supernatural ultra bright intelligent kindness of the soul!)

Or — in other words — not only is Ginsberg with us in Rockland, but he’s with us in Rome, Tuscany, Firenze, Milan, Naples, Sicily, Palmero, Bologna, Florence, Venice, and one or two other places as well.