essays

In Search of the Novel’s First Sentence: A Secret History

A great first sentence is very important. In a novel, it’s a “promise,” a “handshake,” an “embrace,” a “key.” Great first sentences are celebrated everywhere literature is cherished and mandated everywhere it’s taught. They’re a pleasure and a duty — the “most important sentence in a book,” everyone agrees. But they haven’t always been important. When Daniel Defoe wrote the first English novel, Robinson Crusoe, in 1719, first sentences weren’t important, and so he wrote, “I was born in the year 1632, in the city of York, of a good family, though not of that country, my father being a foreigner of Bremen, who settled first at Hull.” When Charlotte Brontë wrote Jane Eyre in 1847, first sentences still weren’t important, and even so she wrote, “There was no possibility of taking a walk that day.”

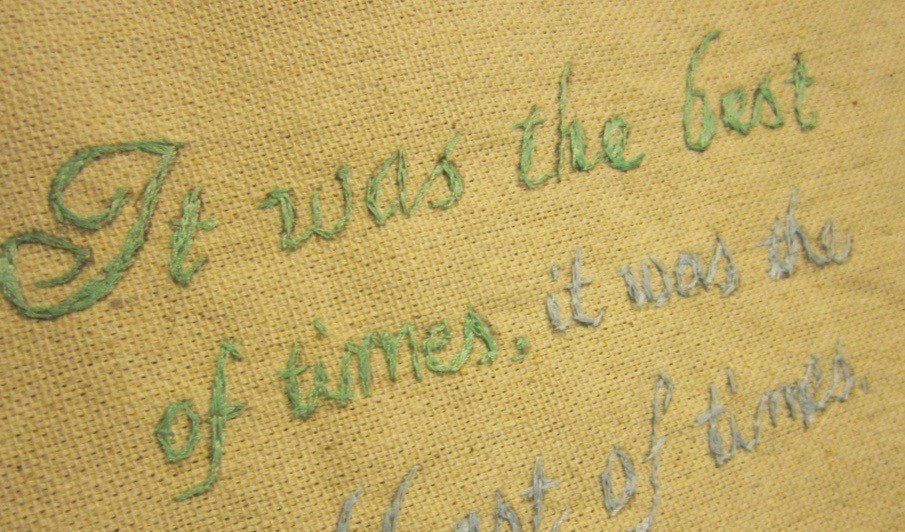

Now we laud this and many other great sentences, but no reviewer at the time thought anything of Brontë’s choice. No one in America was excited, four years later, about Melville’s classic opener to Moby Dick. Nobody had a thing to say about the wonderful beginning to Pride and Prejudice. Nobody was bothered by the pedestrian beginning to The Scarlet Letter, or in love with the beginnings of Middlemarch or A Tale of Two Cities, or unimpressed by that of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. When we celebrate first sentences today, we do so as though they’re an essential feature of the novel. They’re considered as much a part of its form as an envoi is to a sestina, as a battle is to an epic, as a setup is to a joke. But the beloved first sentence is the product of dramatic changes one hundred and fifty years into the novel’s history. There are ample studies of the rise of the novel, but the move that would become the novel’s calling card has virtually no critical history.

…the move that would become the novel’s calling card has virtually no critical history.

To some extent, the gambit’s novelty should be obvious. When the website Gawker last year assembled a list of the 50 greatest first sentences, 48 were from books published after 1900. Most lists will have a few more selections from earlier in the novel’s history, but, as Gawker said, “often the most well-known are not always the best.” Others have noted that many “great” first lines are only considered so because of the greatness of the books containing them. Such older first sentences often look out of place on these lists. But then, what makes a first sentence not great? How did this all become so codified that you can actually look back at the first sentence of Pride and Prejudice, as apparently Gawker’s writers did, and decide it’s not so wonderful after all?

And why so many lists and such love for them? The British magazine Stylist proudly notes that the “Best 100 Opening Lines” list they compiled is their “most popular piece of content ever.” Content-generating websites like Buzzfeed continually return to the first sentence as the ideally piecemeal way to engage a forbiddingly dense form. Traditional newspapers often turn to them for the same reason. They’re so fun that books have been released listing just first lines. There are first sentence card games too. The great first sentence is not just a step on the path to a story but its own self-sufficient enterprise. Is it so easy to extract because it was unnaturally grafted on in the first place?

The earliest novels were commonly named after people, and they begin not with a hook but with the laborious process of laying out a life. Even if they do have a fairly engaging first sentence, as is the case with Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa, they tend to forestall it with a preface. Before beginning, you need to know how the text got to you or, as in Tom Jones, what narrative strategy the author will employ. By 1759, the slow growth had gotten so tedious that Laurence Sterne began his parodic novel Tristram Shandy with a 145-word first sentence that only just begins the process of the narrator’s conception. The book, which across 600 pages barely proceeds past the hero’s birth, at once mocks contemporary efforts to explore a life in excruciating detail and reveals the fruits of such a method. Plot is not on the agenda, just ideas and jokes.

Within fifty years, however, novelists began focusing more on the action. In 1808, London’s Lady’s Monthly Museum offered a list of “Established Rules for the Composition of a Modern Novel, or Romance” that begins, “You must make a point of beginning in the middle of the story: as nothing is more absurd and insipid than letting a person know who, or what, they are reading about, for four chapters at least; and moreover, be sure to let the first sentence be an exclamation of horror, astonishment, or apprehension.”

It’s tongue-in-cheek, but this bad advice isn’t such bad advice. In fact, a novelist today could do well by following many of the writer’s sarcastic guidelines, from making “all handsome personages be amiable,” to concluding each volume with a hook, to “making marriage the sole reward of the good, the ultimatum of happiness, and the only object of female ambition.” Like critics of the first sentence to follow, the writer brings a highbrow, gendered sensibility to the critique of novel openings.

Three years later, Jane Austen would begin her writing career like so: “The family of Dashwood had long been settled in Sussex.” Sense and Sensibility’s opener makes no great first line lists. It’s an old-fashioned beginning, concerned with establishing background. Austen was indeed focused on marriage, but she was not in the popular class that the Lady’s Monthly subjected to ridicule. Like other respectable writers of the nineteenth century, her models were the great, slow novelists of yore. Austen’s next opening sentence, for 1813’s Pride and Prejudice, was more compelling, but none of the few reviews at the time noticed. It’s unclear how much power it might have had. All prior and for many years all subsequent deployments of the phrase “truth universally acknowledged” were completely earnest — arguing for better country roads, against cockfighting, or for Christ. Perhaps readers didn’t even pick up on the irony. Apparently not until 1852 was Austen’s line praised for how it “plunges at once in media res.”

The sentence doesn’t just plunk you into the middle of something; it presents a problem, a paradox, a mystery.

Only toward the end of the century did reviewers begin to highlight the particular effects of first sentences, just as these lines began to look a bit more like those celebrated today. Two reviewers in 1867 pause to celebrate the first sentence of Anthony Trollope’s Nina Balatka: “Nina Balatka was a maiden of Prague, born of Christian parents, and herself a Christian — but she loved a Jew; and this is her story.” Nobody, Scotland’s Aberdeen Journal says, will read this sentence “without being captivated with the beauty of its style and led unresistingly on to read the whole of it.” The sentence doesn’t just plunk you into the middle of something; it presents a problem, a paradox, a mystery. The reader loses control of himself. He has no choice but to follow the narrator and answer the question of just how Nina found herself in this curious situation.

This is the cusp of the first sentence era. Trollope’s choice today doesn’t look ideal, but the reactions are, and the first sentence as it develops is all about the reaction. Whatever it did before, this is what it does — or is beginning to do — now. It gets people intrigued. Witness one reviewer’s response to the first sentence of an 1874 novel that begins, “The great gate closed behind him, and he was a free man.” The bait is obvious, and the reviewer chews it eagerly: “What gate? we are tempted to cry on opening the volume; who was a free man? and why had he not always been a free man? What has he done?” The writer could not have dreamed of a more perfect response. It is such readers to whom all first sentences are dedicated.

From here, reviewers focus more and more on first lines that are “scientifically calculated to awaken interest,” that can render readers an author’s “willing slaves.” In 1887, William Henry Bishop’s The Golden Justice is able “to pique the curiosity of the reader” by opening, “There were many theories about the disastrous collision at the Chippewa Street bridge; but not a word was spoken against that eminent citizen, David Lane.” In 1915, Henry James shows “a flourish of the master hand” in opening, “I remember the whole beginning as a succession of flights and drops, a little see-saw of the right throbs and the wrong.” Starting in media res is a given; the sentences that win praise gesture vaguely toward something specific to get the reader guessing. Who’s David Lane? Whole beginning of what?

Critics were well aware something new was afoot. In 1898, a reviewer for London’s The Graphic describes a work in which “the very first sentence of the novel, proving its complete up-to dateness, is the key to the whole.” “Novels once had a way of inducting the reader into the story by first casting a leisurely backward glance over two or three generations of the hero’s forebears,” a writer for Harpers says in 1917, but now “your modern novelist has developed a sort of literary jiu-jitsu whereby, with the very first sentence, the reader is catapulted off his feet into the very thick of things.” Critics repeatedly look backward to understand how far they’d come. “What surprisingly patient people our ancestors were!” a 1931 Manchester Guardian piece begins. Many of these stories contrast the new beginnings with Sir Walter Scott’s long-winded ones — “one might begin with a puzzle, but not a disquisition” — and it’s surely no coincidence that the Scottish writer’s stature has greatly fallen since. Conversely, people began to recognize that the hitherto little-heralded novelist Scott first championed, Jane Austen, was, as a 1922 story notes, “one of our best beginners.”

A 1932 Christian Science Monitor piece offers the shrewdest assessment of the new art. “The old desire to lay a quick foundation of space and time” is fading, the writer asserts. “Nowadays the beginning of a story may be all atmosphere without actuality.” To explain the change, the writer offers a few examples from Dickens in the old style before finding one that fits the modern norms, from 1848’s The Haunted Man. It begins, simply, “Everybody said so.” Said what? Who is “everybody”? The reader can find out later; for now it is important “to dispense as far as possible with bare fact.” “No longer,” says a 1912 Washington Post essay, will a slow story do that begins with the setting; instead the writer must deliver these details “in small and broken doses.” They’ve figured it out. You’ll find much the same advice in today’s writing manuals.

The changes upset some. “A strong tide of re-action is setting in against the abruptness, albeit picturesque and effective, of the dramatic method in fiction,” writes novelist Hall Caine in 1889:

Like the old fairy tale, the modern novel should begin, ‘There once lived a man, and his name was Jack!’ The simplicity and artistic worth of the method seem to me to outweigh the violence of the outburst with which the dramatic fictionist would begin — ‘Here is a man! Who is he? Listen to his conversation!’ You are plunged into a hot bath of talk and opinion before you have even a nodding, far less a speaking acquaintance with the characters of a book.

One would think a reviewer’s job would be to analyze the least accessible portion of the text — the contents buried deep inside, not what’s available to any browser — but instead they adapted their critical lens to the new market.

But most critics adapted quickly to the new style. In 1894, a review in The Critic begins by lamenting a novel’s inability to master “the trick of the first sentence, that opening move in the game of life.” Advertisements again and again present blurbs praising first sentences. “In a story the first essential is to arrest the attention, and the early pages, or even the first sentence are important from this point of view,” says a reviewer for Country Life in 1899. After nearly two centuries of not even being noticed, now the first sentence is pivotal. “I knew the book was good when I had read its first sentence,” a Times Literary Supplement review says in 1921. “The opening sentence is not happily chosen,” another TLS review laments two years later. One would think reviewer’s job would be to analyze the least accessible portion of the text — the contents buried deep inside, not what’s available to any browser — but instead they adapted their critical lens to the new market.

***

It’s natural that novels would change during this period, since everything else did. Studies such as Alan Trachtenberg’s The Incorporation of America, Richard Ohmann’s Selling Culture, and William Leach’s Land of Desire have all charted the massive cultural shifts wrought by the new centralized market economy that took off around 1880. The changes did not arrive in precisely the same time or ways in America and Britain, but the broader outlines should nonetheless apply to a phenomenon that itself arrived sporadically over several decades.

The most obvious analogue to the novel’s first sentence is the newspaper’s “lede,” a form that developed over the nineteenth century alongside more sensational efforts focused on attracting a mass audience. Being a profession and not an art, journalism was more free to prescribe rules of composition. A New York Mirror piece from 1836 advises, “Periodical writers should be brief and crisp — dashing in media res at the first sentence. Sink rhetorick.” By 1889, the advice was still sound: “Begin with a sentence short, apt, direct, forceful, and, if possible, striking and stimulating.” But here the tip is appearing in a new all-purpose instructional journal, The Writer, “the monthly magazine for literary workers.” For the aspiring novelist, journalism — writing for newspapers or the new national magazines that rapidly spread across the country starting in the 1880s — was increasingly serving as an apprentice discipline, and so it’s no surprise its methods would soon manifest themselves in fiction.

Simultaneously, the short story emerged both as an extremely popular form and as another practice art for the young novelist. The genre had, the writing guide Practical Authorship notes in 1900, “more devotees than all other lines of literary effort combined,” with “avenues for the publication” that were “practically unlimited.” In setting out the rules for this form, many writing guides contrasted it with the more leisurely novel. “Get in media res at once,” the book continues; the genre “will not bear much descriptive work.”

The influence of these forms is obvious, but to get a real sense of what shaped the novel and the culture more broadly at this time, consider another expressive medium that developed alongside these: advertising.

As Roland Marchand discusses in Advertising the American Dream, the revolution in advertising during this period was to learn not simply to explain the product but to make it appealing, not to sell the bare goods, but to invite the buyer into a world, to present at a glance a lifestyle he or she would want to inhabit. For a long time, a 1914 piece in the trade journal The Graphic Arts says, “Most advertisements read like stories where plots were given away in the introduction.” But advertisers came to find, like novelists, that buyers were more easily lured by the vistas the book or product could open up than in the details like the birthplace of the protagonist or the effectiveness of the soap.

That article proceeds to offer a list of effective slogans — just invented in the 1890s — in the new style that function much like first sentences: “Perhaps You Have experienced This”; “Don’t Wish You Had the Boss’s Job”; “It’s Marvelous on White Shoes”; “Not Bad, Considering.” They intrigue with their insufficiency — making the reader feel he or she has been left out of things and eager to get in the know. You could easily slip in Dickens’s “Everybody said so.” Or the first line of a successful novel from 2014: “At dusk they pour from the sky.” Pronouns like “it” and “they” and demonstrative adjectives like “this” draw the reader in, begging further description. What is “it” that’s so marvelous? Perhaps I have experienced “this” what? “To be sure,” the story continues about one of the slogans, “you are not as excited about it as you are over a detective plot, but the thread, though slender, is continuous.”

Having drawn the reader in, the advertiser faces familiar problems. A 1917 piece in the business journal Modern Methods again draws the comparison to a “book or magazine article,” examining how to get from that exciting first line through the essential “descriptive work” that must follow:

The first few words of the printed page have caught our interest as if in a vise, and, almost against our will, we have continued to the end. … But, if you are the advertiser, you want your advertisement to also convey certain information — a knowledge of certain facts…. Throughout the advertisement will be strewn this information — presented so unobtrusively, so subtly that the reader will be scarcely conscious of the fact that he is acquiring it.

Similarly, a 1918 issue of The Writer tells young novelists, “A favorite bit of advice is to make the first sentence plunge the reader into the action of the story, forcing each sentence to carry the story one step nearer the climax and sifting in the necessary explanations as the story progresses without clogging the action at any point.”

Every advertiser was a novelist, every novelist, at least for a sentence, an advertiser.

Between advertising and the novel, the lines of influence are blurry because the new marketplace was blending the forms together, forcing them to change their practices to survive. Every advertiser was a novelist, every novelist, at least for a sentence, an advertiser. Or, as a critic for Life in 1913 describes the work of one first sentence, a street “barker.” When London’s Observer invited readers to submit their favorite first sentences in 1935, the paper found that “More modern openings show an increased interest in the art of the shop-window; some of them are as carefully contrived as ‘traptions’.” Such windows, as Leach’s Land of Desire treats extensively, were yet another dramatic response to the new market. They served both to challenge competitors and create the new desires that would be necessary to keep the economy expanding. “Show your goods,” an industry journal wrote in 1889, “even if you only show a small quantity.” One of the first theorists of the new display practice was eventual novelist L. Frank Baum, who would encourage store owners to “arouse in the observer the cupidity and longing to possess the goods.”

As Marchand writes, America was now for the first time a majority urban population. For the first time in human history, the majority of people the average person encountered in a given day were strangers. Others had no inner lives; they were just the external characteristics visible during a first impression. For advertisers, this meant cajoling people about every detail of their appearance, littering advertisements with scrutinizing eyeballs. And there’s something of this too for the novel-reading public. Adrift in what the era’s writers continually described as a “flood” of fiction, there was no time to create a character ab ovo; he or she must come fully formed, must offer quick and memorable impressions. There are so many other characters to choose from.

In America’s newly developed department stores, books functioned as loss leaders, drawing a sophisticated clientele in and raising the sales and the status of the other goods on display. The first sentence, itself described as a “decoy for attention” in a 1930 story on the new art, is a lure within a lure, created in a new economy increasingly predicated on commercial diversification and instant appeal, in a book market that had never been so populated. Following on already great leaps in book-publishing, the 1890s saw the number of new books released in America double. The passage of an international copyright act further helped elevate new domestic novels. At the same time, a mass increase in paper production led to a drop in prices — a drop further abetted by increased consumption by a now almost fully literate public, which, thanks to an improved standard of living and shorter workdays, had more time and money to spend on books.

The first sentence, itself described as a “decoy for attention” in a 1930 story on the new art, is a lure within a lure, created in a new economy increasingly predicated on commercial diversification and instant appeal, in a book market that had never been so populated.

In 1895 the bestseller list arrived, and increasingly sales were the primary focus of publishers and subject of lament for critics. A 1905 essay in The Atlantic Monthly, “The Commercialization of Literature,” fretted that the more publishers “market their wares as the soulless articles of ordinary commerce are marketed, the more books tend to become soulless things.” Now sold in dry good stores and pharmacies, books must have looked less sacred to buyers as well. The book market was just another market, and thus, less rarefied, given over to the same tricks of product differentiation as other products, from the newly elegant covers to the newly alluring first sentences.

On the one end, the successful author was becoming a figure of esteem and journalism was adding bylines; on the other, books were contracted out to anonymous churners. The editor of the Saturday Evening Post declared he was in “the business of buying and selling brains; of having ideas, and finding men to carry them out.” As Christopher Wilson has shown in his study of turn-of-the century writing, Labor of Words, the simple, forceful literary style that took over during this period was largely imposed by the hugely influential new national magazines, the editors of which sometimes described advertising copy as their model. People began to really forsake the idea of the author as an inspired innovator and instead viewed him as a craftsman. “You must strip off the glamour, dispel the illusions,” a writer for The Bookman says in 1915, “regard your work as a profession to be studied and mastered like engineering or architecture.” This attitude was behind the rise of trade journals like The Editor, The Writer, and The Author, accepting the new demands of the marketplace as the natural terms of art, rules which would be further affirmed by the rise of MFA programs. (Some have recently begun offering courses just in crafting opening paragraphs.) As Wilson writes, literature was now seen as a “product of labor rather than romantic inspiration. Writers and editors now spoke not of an author’s ‘inner muse’ or ‘vocation’ but of the value of ritualized routines, careful sounding of the market, and hard work.” It’s a language that still reigns, and has perhaps, like the importance of the first sentence, become more vigorously asserted as competition has intensified.

***

A new kind of frenzy emerged in writers, as revealed in a well-traveled anecdote of an ambitious young man looking to pen “a modern novel.” When the novice goes to a New York publisher for advice, as a 1913 version has it, he is told “to enlist the attention of the reader from the very start” with something “unusual and bright.” Soon, the publisher receives the fruits of that advice, a novel that begins: “‘Oh, hell!’ exclaimed the duchess, who up to this point had taken no part in the conversation.” The joke grew so popular in a literary world awash in ham-fisted attention-seeking, that Hell! Said the Duchess was taken as the title of a 1934 novel.

Such shouts signaled more than just lack of talent. Critics were learning to read the first sentence as a cue of genre — and gender. A 1902 piece in Book-Lover begins, “’Tis said that the average man, in taking up the latest successful novel, turns anxiously to the first page of the first chapter and from the hurried reading of the initial sentence judges therefrom the real worth of the story.” This man apparently still wants an opener that names the character and situates him in a place. “The average woman,” however, either turns to the last page for a happy ending or to the first for a yelp: “‘Janice!’ called a voice.” We already saw this in 1808, and a century later the association of opening dialogue with female writers really takes hold. Hence in 1900, a writer for The Bookman says: “There was a time when this conversational beginning was very striking and satisfactory… But the female novelist came. She saw. She conquered.” She began her novels, this and other critics complained, with the shout, “Ma-ry!”

Critics wanted a little more subtlety and depth to the first sentence. In 1930, The Short-story Craftsman set out rules that largely still hold: “Striking, that first sentence should be; short, very short, lifted from the midst of affairs, and Janus-like, looking backward as well as forward.” Yet the reader must avoid “scare-line openings, which, though appropriate enough, are patently designed to arrest attention through the sensational, the bizarre.” The writer cites a novel that begins, “Mrs. Balflame made up her mind to commit murder.” It’s ideally short and gets into the middle of things, but its mystery is too obvious.

Modernism positioned itself as an antidote to what Henry James in 1900 called the “vulgarization of literature.”

The article concludes with a list of six story types and the six sentence types best paired with them. An “action” story requires an “action opening”; a “psychological” story calls for “character analysis.” It’s not terribly complex. In 1936, Britain’s Observer held a contest to write a great first sentence for a nonexistent novel, and the genres aimed for in the responses are often clear: “A scared-looking, brown, rough-haired mongrel dog came tearing down a solitary street, carrying in his mouth a human hand.” Whose hand? How did a dog get a hold of it? The reader is plunged into a mystery. Most of the favorites tended toward the sensational, as did those in books actually published. Two years earlier, The Postman Always Rings Twice hit shelves, and nearly every review and advertisement praised the bestseller’s intriguing first sentence: “They threw me off the hay truck at noon.” Who? Why? Etc.

That’s a classic “genre novel” from the period that began to create such distinctions. At the turn of the century, the romance was the most popular seller, hence all the sexist complaints about women writers and readers. They were being blamed for the changes wrought by a newly mass marketplace. The readers of the “classics” of half a century ago had all come from upper classes, but now the majority of readers went for low and “middlebrow” fare (the latter term being invented in 1906 to describe the changes). Against these shifts, the likewise fragmented mode of Modernism developed, with its own detailed attention to craft, to fine-tuning “the shape and ring of sentences,” and rescuing words, as Joseph Conrad put it, that had been “defaced by ages of careless usage.” It sought to be, in the words of Ezra Pound, a “counter-current” to the mainstream. “Literary modernism and modern public relations emerge before the public at precisely the same time and in close association with one another,” Michael Norris writes in Reading 1922. Modernism positioned itself as an antidote to what Henry James in 1900 called the “vulgarization of literature.” And this point of differentiation tends to play out in the first sentence, be it in the Modernist novel or the vaguely-defined “literary” one of today. There’s still a mystery there but not a flashy one of a dog with a severed hand.

For the literary novel, the ideal first sentence usually suggests a novelty of outlook rather than plot.

It tends, rather, to offer a mild intrigue, a more abstract one. One of the Observer’s unpublished first sentences — a favorite exercise as early as 1900 — tends in this direction: “‘Are your eyes blue or grey, Marguerite?’ asked young Mr. Arnold, of Balliol, as they stepped ashore at Thun.” While the writer hasn’t yet learned to “sift in” the details until later on, she understands that a compelling mystery can be just a subtle little oddity. For the literary novel, the ideal first sentence usually suggests a novelty of outlook rather than plot. Sometimes, this is an epigrammatic first sentence, like Austen’s. More often, it’s some of those vague pronouns or adjectives that feel especially freighted, as in the celebrated (at the time) first sentence of Woolf’s Jacob’s Room, which concludes, “there was nothing for it but to leave.” What’s “it”? An ill-defined article works just as well: “The letter said to meet in the bookstore.” What letter? The method is simple, but effective. In the last five years, 62 of 200 New York Times “notable” novels have deployed this trick.

Very often, a successful literary first sentence involves some sort of odd yoking. The beginning of Orwell’s Coming Up For Air is typical: “The idea really came to me the day I got my new false teeth.” Not only is there the vagueness of “the idea”; there’s also the question of just what sort of fascinating idea could come from false teeth. Marquez, whose sentences always make the lists, is a master of this technique. His most celebrated novel, 100 Years of Solitude, opens, “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Sure, there’s killing going on, but what you want to know about is a simple childhood experience. His second most celebrated novel, Love in the Time of Cholera begins, “It was inevitable: the scent of bitter almonds always reminded him of the fate of unrequited love.” Again, the mystery is human, slight. Like with Orwell’s teeth — how are those things connected? Even a page-turner like Gone Girl signals its higher aspirations with a focus on the mundane: “Whenever I think about her, I always think of her head.” The literary novel imposes some rules of decorum, but it’s as important to intrigue as in any genre novel.

The literary novel imposes some rules of decorum, but it’s as important to intrigue as in any genre novel.

As a critic wrote in 1912, “‘It was a dark and stormy night’ will no longer suffice.” By 1982, the idea was so assured that faculty at San Jose State University set up a contest to mock efforts that fall furthest from the first sentence ideal. They don’t just mock the eight words Snoopy spent decades playing with, but the full sentence with which Edward Bulwer-Lytton began his 1830 novel Paul Clifford: “It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents, except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.” It’s pretty bad, but all these qualifiers, including that silly parenthetical, used to be popular. Many bestsellers from the turn of the last century begin just as choppily. Long-windedness, especially of a tongue-in-cheek type like Bulwer-Lytton’s, could be kind of fun.

And still is, clearly, to those partaking in the contest. And if you examine the winning entries, you’ll find they’re equally about mocking the present as the past. They don’t just meander the way an 1830 opener might; they meander while jumping right in — using speech and pronouns, and all the obscuring tricks used to captivate a reader today. Like “Hell! said the Duchess,” the contest is just another manifestation of the frenzy every writer is still under to meet the demands of the market, a way of paying respect to the lash raised above them.

Whereas Bulwer-Lytton could comfortably begin a novel with a sentence offering nothing more than description, today “bare fact” will not play. Just eight of the 200 Times notables begin with a focus on setting, and none are from debut writers but instead established pros — Zadie Smith, Jhumpa Lahiri, Richard Ford — who have already captured readers and so earned the right to ease into things, to be dull. Yet even as the first sentence was beginning to bloom a hundred years ago, you could still find plenty — maybe a majority — of writers who gave no thoughts to a hook. Here’s the first sentence from a bestseller in 1895: “It was a fine, sunny, showery day in April.” And 1920: “Overhead the clouds cloaked the sky; a ragged cloak it was, and, here and there, a star shone through a hole, to be obscured almost instantly as more cloud tatters were hurled across the rent.” Who gives a shit?

Even as articles were suggesting that novelists would “take no chances with a volatile reader,” there apparently wasn’t much pressure from publishers on this point. Indeed, in perusing writing guides from that era — when such books began — there is almost no attention to openers. Alexander Good’s Why Your Manuscript Returns, from 1907, encourages writers to “grip the reader’s interest at starting, with the very first word,” and Arnold Bennett’s How to Become an Author, from 1903, similarly says the writer should “plunge in” rather than “begin with descriptions or explanations,” but that’s all I could find on first lines. Dozens more simply ignore them. Much more attention is paid to the etiquette of approaching the publisher and how to format a manuscript. And why should writers worry about first sentences when the writing guides written by publishers assured that they gave thorough readings? In 1905’s A Publisher’s Confession, Walter Hines Page of Doubleday writes: “If they are above the grade of illiteracy somebody must read a hundred pages or more to make sure that the dullness of the early chapters may not be merely a beginner’s way of finding his gait.” Other guides and memoirs suggest such reading practices were the norm.

Today, unpublished authors are routinely warned their fate rests on their first sentences or, at most, pages. It’s the only way to hook readers, it is said. The validity of this idea is unclear. Early market research made no mention of first sentence perusals. In discussions of book selection online, readers much more commonly say they buy because of the cover, blurbs, and recommendations, which aligns with what little market research today is public. Those who do sample the prose say they read somewhere from the middle as often as the beginning. But if the first sentence’s deciding power for buyers is uncertain, the idea at least serves as a viable cover story in a world where more people than ever want to be writers. The first line serves, former agent Mike Nappa writes in 77 Reasons Why Your Book Was Rejected, as “the first line of defense from editors and agents who want to reject your work.”

Much has changed in publishing since Charlotte Brontë wrote her lovely first sentence. Those ten words began a manuscript that was sent unsolicited, under a pseudonym, to a London publishing house in late August of 1847. By mid-October it was on bookshelves. With a mass market have arisen massive new hurdles to publication. In discussing the overwhelming number of new books in 1902’s Our Literary Deluge, Francis Halsey praised publishers for having “served us most effectually as a dam.” If publishers then appear more forgiving than those of today, it may just be that everyone then was unready to accept, or be honest about, how radically things had changed — how much the novel had been bent to fit a market that wasn’t built for art.

One could imagine lumping them in with clickbait headlines and sensational covers — the thing you apologize for while recommending the text to a friend: “It’s actually quite good once you get past that.”

Since then, literary terms of praise often sound like capitalist ones. There’s the emphasis on “craft,” a discourse, as we’ve seen, created in response to the new economy. There are those periodic celebrations of literary coteries in which all members are improved through competition. And there’s all these celebrations of the first sentence, dressed up as a “promise” or a “handshake” when the most accurate metaphor may be — often applied without judgment — “advertisement.” But it’s still easy to imagine a world in which the first sentence isn’t celebrated but treated as an embarrassing plea for attention, even the subtle ones — maybe especially the subtle ones, trying so hard not to care. One could imagine lumping them in with clickbait headlines and sensational covers — the thing you apologize for while recommending the text to a friend: “It’s actually quite good once you get past that.” Indeed, the demonstrative adjectives so popular in advertisements and first sentences have recently been shown by the analytics firm Chartbeat to be the most successful headline-writing gimmick.

But in normal circumstances, who wants to be subject to a great opening line, be it from a salesman or some guy at a bar? It’s an insult. (Or maybe this line of thought is only the cynical result of reading hundreds of them. I certainly don’t judge modern novels by their formulaic first sentences. That would be silly.)

“Great first lines” are damningly useful. They help agents and editors weed through their piles rapidly, and they give the media a quick entrée into a plodding subject. They’re the fun public face of the private reading experience. They allow a common conversation about books like Moby Dick that maybe not everybody has read, and perhaps invite them to do so.

But in crafting a form that works well outside of the novel, the form of the novel itself is confined. As Henry James noted of many of the changes in the book marketplace in 1900, the “form of the novel that is stupid on the general question of its freedom is the single form that may, a priori, be unhesitatingly pronounced wrong.” And yet many critics today will lament a first sentence that doesn’t fulfill the guidelines. In a 2011 NPR roundtable on first sentences, critic Stanley Fish complained that one by Pynchon didn’t work, that it didn’t “do the forward-looking work that first sentences can do.” Can, but should? For a 1985 New York Times story on first sentences, Frank Herbert spoke of “what a narrative hook is supposed to do — it gives you the key, the essential of what you’re going to read about in a tantalizing way. It grabs you and hauls you bodily into the story.” But is it always a good idea to leave the key under the doormat? And why can’t the reader find his or her own way in?

Paradoxically, the great first sentence, the most extractable part of the novel, is celebrated for its intimate connection to what follows. It’s “the DNA,” Gloria Naylor has said, “spawning the second sentence, the second, the third,” and so on. But the ease with which people construct orphan great first sentences suggests otherwise. To really put that first sentence within the continuous stream of a novel, maybe something less attention-getting is called for, something like “It was a dark and stormy night.” Familiarity aside, it’s a fine sentence. Really. Some nights are darker than others. Some are stormier. The sentence is clean and simple. Certainly, you’re going to want more compelling sentences in the book you’re holding, but a novel shouldn’t have to put its most artful foot forward. Sentences of course can telegraph the future; they can confuse; they can tantalize. But if they’re not allowed a more humble scope than this, then they’re in danger of fleeing the novel — being less important to a book and its readers than to the desperate tussle of financial concerns that pull at it. There’s a danger that a great first sentence might be nothing more than a great first sentence.