essays

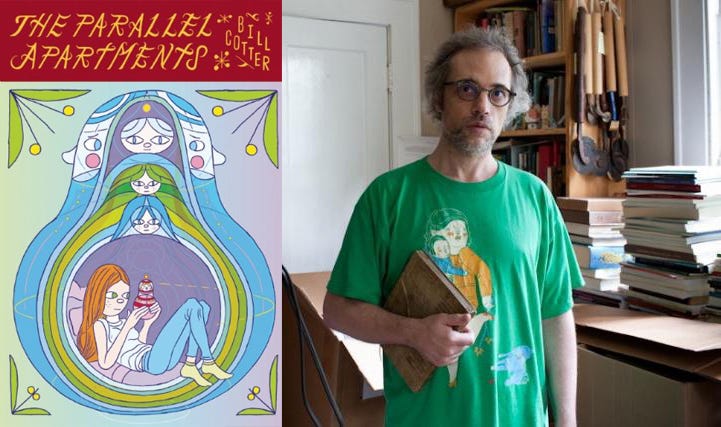

INTERVIEW: Bill Cotter, Author of The Parallel Apartments

by David Eric Tomlinson

Bill Cotter was born in Dallas in 1964 and has labored as an antiquarian book dealer and restorer since 2000. He presently lives in Austin with his girlfriend, the poet Annie La Ganga. Cotter’s second novel, The Parallel Apartments, was released last month from McSweeney’s.

So you’ve lived in Texas all your life?

My family moved around Texas until I was about eight, then my dad’s job took us to Tehran. We lived there, and in a good-sized city in the south called Ahwaz (128ºF in the summer!), until the increasingly fragile political climate obliged us to move back to the States, where we settled in a suburb of Boston. I came to bloody hate that city and Massachusetts, in fact the whole Northeast, and was glad to be out of that ice-locked Hades in ’93, when I moved to New Orleans. After a couple years there, and a depressing year or so in Las Vegas–what an awful place–I settled in Austin. Sorry to be so negative about the world. I like Austin pretty well.

You write great sex scenes. There’s tension, there’s something at stake. It’s engaging. Sometimes it’s hot. Sometimes it’s really uncomfortable to read. There is a philosophy or point of view about desire in this book I’d like you to talk more about. Near the end of the novel, for example, one of the characters, Lou, gives the following advice to a would-be murderer, trying to steer the kid in a new direction: “If a criminal wants to express genuine sorrow, and hurts himself, it will be seen as the criminal simply getting what he wants. The criminal, in order to be truly penitent, may not have what he wants, no matter how self-destructive or painful or steeped in real remorse.” Your characters seem damaged, unable to get what they want, and they turn to sex (or Cheetos, or soda, or some brand name beer) to fill that need. What’s this book’s philosophy about “want” vs. “need”?

I think that need is often just an accelerated cousin of want.

Real people may say they need sex, or love, or to know the circumstances of their conception, or Andy Capp’s Hot Fries, but of course they really, merely, want those things–they just want them wicked bad.

I felt like it was my job, as the author, to convince the reader that my characters’ wants transcend to true need, that the acquisition or knowledge or consumption of certain things that are in truth just wants whose fulfillment won’t matter in terms of the characters’ abilities to persist in living, become, in the reader’s mind, unequivocally necessary to their survival, as snakebite victims need antivenins, as astronauts need spacesuits, etc.

How long did it take to write the book?

About five years, though two of those I spent in a consumptive depression, during which it seemed every word I wrote was utter garbage. Even though I worked on the book during that time, I destroyed everything I wrote; no writing survives from that period. (I did a lot of Sudoku puzzles, though.) The book, when I originally submitted it, was half again as large; roughly 250 pages were cut in the editing process.

Wow. That’s almost another book. Have you started another one?

I think the book is better for the edits, however substantive they were. Both the editors, Adam Krefman and Andi Winnette, are brilliant and keenly insightful. Luckily I was able to squeeze a couple short stories out of the excised smithereens.

I’m working on a collection of stories now; I expect the MS to be ready in a few months. Another book, a middle-grade adventure novel titled Saint Philomene’s Infirmary, is finished and under consideration. Last, I am working on another novel, this one about small, isolated Texas town in the early 1970s, in which a larger-than-life character, a brutal, Nero-like man who railroads, controls, terrorizes, extorts, threatens, and even rapes people in the town, some of whom eventually conspire to kill him. They succeed, in broad daylight, and no one is ever prosecuted. No witnesses come forward, even though everyone in town knows who did it; such was the hatred for the man.

The problem with this story–and I learned this quite awhile after I’d started writing it–is that it’s already been told: There was a famous true story in, I think, the 1980s, that is eerily similar to mine–little town, tyrannical man, widespread hatred, his unsolved murder–and notorious enough to merit the production of at least one made-for-TV movie. It makes me wonder if maybe I’d read about the affair, or saw the movie at some point, then suppressed the memory, which eventually bubbled up again as my own invention. This is worrisome. What else do I think is my own work but is in fact a precipitate of a buried remembrance? So I’m in a quandary. Finish it or not? Probably not. Which is too bad–I like the first paragraph.

I want to go back to the depression you mentioned earlier. If you don’t want to talk about it, just tell me to butt out, and we’ll talk about something else. Do you think you wrote your way out of that period? Or did you somehow navigate the depression and then after it was over, your writing took off again?

I don’t mind talking about the depression at all. I’m actually in the middle of writing an essay on creativity and depression. I wasn’t able to write my way through my most recent episode. I find it almost impossible to do anything creative (and sometimes to do anything at all) when in the harrows of it. In fact, with the possible exception of the elegant suicide note, I believe it’s nearly impossible for any writer to produce while pressed into the floor of a major depressive episode (although Plath claimed to have written the Ariel poems while in a steep depression).

I was lucky: After a couple years my doctor tried a cocktail of medicines that just happened to work. Most don’t. And antidepressants will sometimes tank out after a period of time, sending one back to oblivion. Fortunately there are a lot to choose from these days. (There is also ECT, which has been very effective for me over the years, though its benefits are short-lived.) In any case, I’m not burdened with the noonday demon at the moment, and have been able to write.

I’ve heard people say that depressed people have a slightly more realistic outlook on life than the rest of us. Which leads me to the way you’ve ended The Parallel Apartments. As the book sprints toward its violent, cathartic ending, everything kind of goes haywire for your characters. But then the forces of law and order step in, everything basically works out (or, as best as could be expected). But you’ve made an interesting choice, in that the ending is dependent upon a lie, or a fiction, told to your protagonist, Justine. Do you think happy people, or happiness in general, is based on deception? Or make-believe, or whatever you want to call it?

No, I don’t think happiness, or contentedness, is based on or dependent upon deception–though it certainly can be–nor is it necessarily based in truth, though that’s possible, too. I think happiness, or any demeanor, is dependent upon circumstances in the short and long runs, be they rife in lies or teeming with truths. In the novel (if I may shift non sequitur), the protagonist, Justine, is told a grand lie throughout her childhood in order to protect her, to keep her happy, or so the lie-tellers believe, and when she discovers the truth, she is not happy, to put it lightly.

What are you reading right now?

Barry Hannah’s Yonder Stands Your Orphan, Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, Al Columbia’s Pim & Francie, and The Best American Short Stories 2013. I just got a copy of Strout’s Olivia Kitteridge, which I’m really looking forward to.

Cotter’s tour schedule for The Parallel Apartments can be found on McSweeney’s.