Interviews

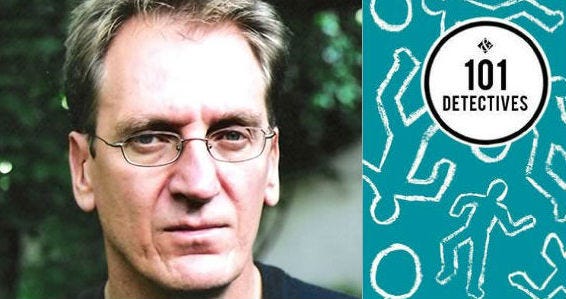

Ivan Vladislavić on Neighbors & Strangers in Apartheid Era South Africa

by Katie Kitamura

The following is an excerpt provided by our friends at BOMB.

Read Kitamura & Vladislavić’s full conversation in BOMB’s spring issue.

I should probably confess that I came to Ivan Vladislavić’s writing late. I can recall the exact sequence in which I read his books, out of chronological order, or rather in a chronology that remains personal to me. First The Folly, then Double Negative, The Restless Supermarket, Portrait with Keys, 101 Detectives — a succession of radically different texts, each defying categorization.

I had the sensation of making a true and immediate acquaintance with a writer whose work occupies the territories of fiction and nonfiction, as well as the no man’s land between. The writing has a quality of unpredictability, a wildness that seeps through the fabric of Vladislavić’s peerless linguistic control. He works like a sculptor, with a deep sense of the material capabilities of language — in some places the prose is dense and opaque, in others near translucent.

This precise verbal manipulation facilitates narrative experiment, casual eruptions of form. Perhaps because of this, I don’t really know what to expect from his next book — I expect only to have my expectations overturned, my sense of language transformed. A public reading at the Community Bookstore in Park Slope formed the basis for the following conversation, which was subsequently expanded in writing.

Katie Kitamura: As soon as I finished The Folly, I ran to the nearest bookshop and asked for whatever Vladislavić they had in stock. The book I came away with was Double Negative, which was written almost twenty years after The Folly and is in many ways very different. But it struck me that the common thread between the two books — and maybe even across the entire body of your work, published over roughly two decades — is the idea of an encounter with a neighbor. I wonder what neighbors, both literal and symbolic, mean in your work and in the context of apartheid South Africa?

The apartheid system was about putting physical space between people. The idea is there in the word itself.

Ivan Vladislavić: The apartheid system was always about relations between people, about determining the nature of those relationships, and very often about disrupting them. I grew up in the most oppressive period of apartheid: I was at school in the ’60s and I went to university in the mid-’70s, just before the first cracks really began to appear in the system. My imagination was shaped in a period of extreme rigidity in the social and political systems. The apartheid system was about putting physical space between people. The idea is there in the word itself. It’s about setting things apart and setting people apart. So an encounter with the other, with the neighbor or the stranger, has always seemed central to me; first to understanding the system as it is, but also to unlocking it, to changing it. It’s really on that level — the encounter with another person, closing the space between two people — that the system has to be undone.

KK: Your books don’t simplify the complications of that encounter. The characters don’t walk away with some sentimental notion of shared humanity. They encounter the other and there are all kinds of differences that have to be negotiated, differences that are sometimes intractable and even dangerous. As you said, the novels are really about contested spaces in a charged political situation. Space operates in very interesting ways in your books. For instance, Portrait with Keys has an observational, documentary eye — as if you’re traveling through the spaces of Johannesburg with Frederick Wiseman’s camera eye. But then in The Folly or The Restless Supermarket, space has a more clearly allegorical function. How do these different kinds of spaces operate in your fiction and nonfiction?

IV: I am fascinated by how the political system gets reflected in the physical space and how the space, in turn, shapes the kinds of social relations that are possible. These concerns are central to Portrait with Keys. In the transition period, when South Africa began to change rapidly, it was very hard to understand the big processes and to see exactly what was happening. You knew that there had been a huge shift in the political order, that a new dispensation had been negotiated and so on. But what effect it would actually have on the society was difficult to gauge, because you could not easily grasp those big abstract processes. For me, a way of understanding what was happening was to look quite closely at the immediate surroundings. It seemed to me that you could understand large, complex processes by looking at what was going on in your neighborhood. So that was when I began to document things — Portrait with Keys is a sort of documentary fiction, or documentary nonfiction. Documentary something or other. Let’s say I began to document, in a more conscious way, these small shifts in the environment as a way of trying to understand how the society was changing.

In Double Negative, I was influenced by the particular technique or approach to space that the photographer David Goldblatt uses. As you know, the novel was generated in response to some of his work. One of the things that intrigues me about Goldblatt is how he’s used space to understand movement and change, by returning to particular sites and rephotographing them over long periods. The photograph is normally thought of as this fragile moment that disappears, and also as a frozen moment. Goldblatt has found a way of putting the photograph into motion, by somewhat obsessively circling back to places that he’s photographed before. So when you look at the photographs beside one another, you get an extraordinary sense of change, captured in just two or three images. In Double Negative, I tried to employ a similar strategy. The narrative is structured as three cross-sections through time, and it returns to some of the same spaces in different periods as a way of gauging social change. So I’m not sure I’m answering your question, but it’s a way of looking at social processes and abstract processes by spatializing them.

KK: At the end of your most recent short story collection, 101 Detectives, there are two intriguing pieces. One consists of a series by Neville Lister, who is a character in Double Negative — a work of text and photographs that was actually shown in a museum context. And then, there are the “Deleted Scenes” from all the short stories the reader has just read. These pieces made me think of the end of Chekhov’s “The Lady with Lapdog,” when the story suddenly enacts a pivot. The entire time the story appears to be tending a small and particular universe, indicating its fictional terrain, and then suddenly it opens up in this very radical way.

A lot of your work seems to have a similar concern. It’s about insisting on the contingency of what we’re trying to make in fiction, which is something writers can be nervous to do. Is it the case that you are trying to open up your fiction?

I’ve become interested in the stuff that gets left out of the book…I’m aware as an editor and as a writer of how much writing never fits into the book — how much is lost..

IV: I hope so. Again, I don’t mean to harp on the past, but my work comes out of a literary tradition in which things were closed off, in which meanings were very certain and people knew exactly what they thought about a whole lot of things. From the beginning I was interested in trying to write in a way that would open up rather than close down meaning or association or whatever. I hope the “Deleted Scenes” work in that way. I’ve become interested in the stuff that gets left out of the book. This is something I should probably keep to myself, but I’m aware as an editor and as a writer of how much writing never fits into the book — how much is lost, if you like.

Anyway, I got the idea from watching DVDs that include a set of deleted scenes at the end. You can see exactly why some were left out of the movie, but every now and then you see one and you think, Well, that’s the whole movie right there! Why didn’t they put this in when it’s the key to the movie? Perhaps they’re the scenes the director left out because they’re the most obvious expressions of the themes. There are all these different possibilities. As a text editor, I’m aware that something similar happens with books, but in the written world we’re more likely to pretend or insist that the thing is perfect, that the text is inviolable and unalterable. And actually it could always be different. So the “Deleted Scenes” in 101 Detectives are there to get the reader hopefully to rethink some of the stories, and also to call the stories to mind at the end of the reading, because I like to think of the story collections as books with proper connections between the pieces. Readers and publishers tend to approach a story collection as a haphazard gathering of whatever the writer happens to have written, whereas I like to structure the books and write pieces specifically to make the sequence coherent. “Deleted Scenes” includes one outtake from each story and this requires you — if you’re this kind of obsessive reader — to go back and identify which deleted scene belongs with which story. You’re kind of being strong-armed into looking back at the book, and hopefully constructing it in a different way.

Read the rest of Kitamura & Vladislavić’s conversation at BOMB.