essays

James McBride Explains Why He Writes Memoir

by James McBride

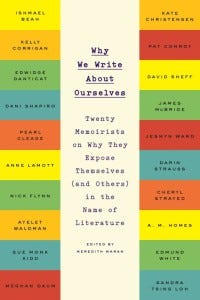

[The following is an excerpt from Why We Write About Ourselves: Twenty Memoirists on Why They Expose Themselves (and Others) in the Name of Literature which will be published by Plume this week.]

Why I write about myself

Before The Color of Water came out, I did a lot of stuff that failed. I worked in musical theater and I failed in that. If you put my musical theater resumé together, I would look like a pretty promising composer, but it wasn’t like Stephen Sondheim was spinning around in bed at night worrying about me. Neither was Wynton Marsalis. Or Tom Wolfe or Kurt Vonnegut.

I didn’t know what a memoir was when I wrote Water. I didn’t pay any attention to the label of memoir versus nonfiction versus fiction. I just thought it was a good story and I had to tell it.

I don’t really care what anyone else does. I don’t follow the careers of other writers. I work with blinders on. I know what I have to do. The book I wrote as a memoir might be the kind of thing another writer would write as fiction.

I don’t follow the careers of other writers. I work with blinders on. I know what I have to do.

Water started with a magazine piece I wrote for the Globe back in the early eighties. I was talking to an editor there, and somehow or other the subject of my mother came up. I mentioned that I was pretty sure she was Jewish, and he said, “You should follow up on that.” So I did, and I found out that she was; and I wrote about what I learned, and it was published in the Globe and the Philadelphia Inquirer on Mother’s Day.

After that I started writing a book based on the magazine piece. I worked on it a little at a time. I went to Africa. I did my work for the Globe. I worked on the book when I could. The finished book might feel like the writing of it was immediate, but it wasn’t. It happened over time, in bursts, and most of the time I spent on it was research.

The older I got, the more I began to appreciate who my mother was. I did the work because I started to see that my mother was very interesting. It was kind of an evolutionary process that happened as I was maturing into my late twenties, early thirties. I was starting to see the world a little more clearly. I started to see that in the world at large, the stuff we hadn’t considered very important was actually incredibly important: race, religion, money, power.

But I didn’t have any specific aspirations when I wrote Water. I just wanted to get the rest of the advance. I don’t really find my musings to be strong enough to justify my writing a memoir. I don’t have that kind of patience. I just don’t think I’m that interesting.

Lean times, lean book

Water came out in 1996. At the time I was a full-time musician, traveling a lot, playing a lot of crummy clubs, eating bad food. I was struggling, really. And the leanness of that life probably had an impact on that work in the sense that I wanted it to be done, and I didn’t want to be driven by the kind of angst that was kicking me around in those years.

The narrative of the book was as thin and as muscled as my life was at that time. You know, with every story you do, you’re trying to shove a lot of things into the keyhole and drag the reader with you. You have to narrow the focus of the story so it has the push of a creek in a narrow spot.

Struggling is good for writing

My life is still a struggle — just a different kind.

A year ago I started a music program in the church my mother and father founded in the same housing project where I was born. It’s a lot of work. If I could retire and do nothing else I’d probably just do that. It means so much to me to do it. There’s a lot of struggle involved in getting these kids into church and into this music program.

I think that kind of struggle is important for a writer. I think it’s a mistake for a writer to sit around coffee shops musing about bullshit. I think it’s a waste of time and I never do it.

I think it’s a mistake for a writer to sit around coffee shops musing about bullshit.

The people I work with in the church don’t know I’m a National Book Award winner. They don’t know about The Color if Water. Most of them haven’t read any of my books. Many of the older ones knew my mother, or knew of her. We’re connected in that way.

I don’t like sitting around talking about work. Invariably it ends up with, “I didn’t like this book for that reason; I didn’t like this one for that reason.” A writer can’t be too negative. You have to have a little bit of innocence to be a good writer. Whatever you have to do to preserve that innocence-the “is that so?” element — you should do it. You can’t be someone who knows everything-”been there, done that.” If you know every thing you shouldn’t be a writer. You should be God.

You need that sense of discovery as a writer, and part of that comes from the attitude you have. You have to stay away from people and places that foster cynicism and bitterness.

If I work hard at anything, it’s that. I still take the bus. I still move around in circumstances where people don’t know who I am. Because I ain’t nobody, really. I’m still the same person. When I started writing, I didn’t really know what writers did. I thought they sat around drinking coffee and sleeping with one another, then writing about it. I’m more of a writer now than I was then, but I’m still not one of those kinds of people. I don’t go to writers’ conventions or do big writer talks.

Ready, aim, don’t fire

When you’re writing a memoir, you have to be careful because you don’t want to bruise people too much. You have to give people the benefit of the doubt.

It’s really not beneficial on the page or through a blog or through any sort of written public word to blast people, unless they are truly deserving. A scamming lawyer or politician yeah, you can aim your bazooka on them directly, and drop the hammer on them, and sleep tight.

But most of us don’t deserve that kind of treatment. If someone’s a racist or a sexist or a homophobic idiot, you have to kind of leave them to God. Just show them as they are, but don’t blast away. Because everyone is capable of change.

Writing a memoir, you have to keep that in mind. You can’t use a book as a kind of “I’m going to get back at them” exercise. You’re not writing it for that reason. You write a memoir for the same reason you write a song — to help someone feel better. You don’t write it to show how smart you are or how dumb they are. You’re trying to share from a sense of humbleness. It’s almost like you’re asking forgiveness of the reader for being so kind as to allow you to indulge yourself at their expense.

You write a memoir for the same reason you write a song — to help someone feel better. You don’t write it to show how smart you are or how dumb they are. You’re trying to share from a sense of humbleness.

When I was writing Water I was very careful to respect my mother’s family. I was very cognizant that most of those people didn’t know me or any of my siblings. I didn’t want to tommy gun them. They had no choice about what happened. My mother did something that wasn’t that cool, given where she came from. She broke free from the constraints of her life. I was raised to believe that everyone is different. The things that work for you may not work for other people. So I was careful to change their names to protect their privacy.

I kept my siblings out of the book as much as I could. With regards to my own privacy, I didn’t dramatize it or soft pedal it. I played it straight. I didn’t really like divulging some of my activities as a high school kid. I’m ashamed of that stuff. I was not real pleased about putting it on the page, but I did it. And I did it without mentioning my friends who were involved.

Postracial publishing? Not so much

Publishers love the idea of a black person who’s showing they were a thug doing dope and crack-the whole business of “I was lost but now I’m found; I was blind but now I see.” This is a real problem for black writers. The industry is accustomed to black writers writing about pain and struggle. I can think of a half dozen white writers who write about the same things and never had to deal with being marginalized. They’re just seen as writers, period.

There’s very little room in the publishing industry for minority writers. I don’t know if that’s anyone’s fault. The industry tries to address the problem, but essentially it’s a personal one. Each of us has to do what we can personally do to inch things forward just a little bit.

Another problem for black writers is that black people simply don’t read enough. If you say that, people get insulted, but it’s true. I have tons of black readers now, but when Water came out most people who came to the early readings were white women and white Jewish women, and I was thankful they showed up.

I happen to think that a good black writer is the one who writes a book anyone will like. If a writer’s good, readers will read those books and feel illuminated. That’s the only way our industry will continue to grow. We have to embrace writers who are different just like we embrace a president who’s different. If we don’t, as a society we’ll wither on the vine.

I wouldn’t say it’s getting better for writers of color. There are better and better writers of color, but they’re not getting a shot. A lot of really good Asian American writers are starting to publish, like Chang-rae Lee, but I have yet to see a plethora of books by Americans of other hues.

To make our industry relevant we need really good editors who aren’t looking for the next Hemingway, but for the next Tupac Shakur.

It’s not just a function of prejudice. The publishing industry is under so much pressure. A writer gets a book deal, and the book gets trotted out for six weeks, and if it doesn’t sell, it’s gone. So many young writers go through that. They don’t have a shot at a second or third book. That’s a real problem that’s industry-wide for all writers.

To make our industry relevant we need really good editors who aren’t looking for the next Hemingway, but for the next Tupac Shakur.

It’s bigger than a publishing problem. We have a great black president, but what would happen if we had a great black vice president? A great black Speaker of the House? Why is it okay to have one black neighbor, but when ten black families move in, the neighborhood changes and stores close down-the kinds of problems that Detroit has right now?

Compared to the problems most people have, these are good problems. I don’t want to bellyache about them.

Blah, blah, blog

In this world of blogging and telecommuting and Twitter, memoirists have to speak to deeper things.

We’re writing memoirs 140 characters at a time, which means we’re basically writing nothing. If you’re writing nothing maybe you’re living nothing. Before you put your story down, first change the manner in which you’re living. If you do that, you won’t find yourself writing a Broadway show with five minutes of spiritual uplift and then everyone goes home.

If you walk around with earplugs in, that won’t give you something to say. Nothing you’re going to write will be of import. Put those earbuds away and join the Peace Corps in Peru. That’ll give you something to work with.

James McBride’s Wisdom for Memoir Writers

- If I were an aspiring memoirist, the first thing I’d do is go visit my grandparents for a couple of months. Drop everything and stay with them. Cook their food. Deliver their groceries. Go to bingo night with them. Let them pull you backwards into their lives. Whatever they have to say is a bankbook for you as a memoirist. You’ll see yourself in everything they do, even if they drive you nuts.

- Know that the writing will lead you into places you can’t imagine you’ll go. In my experience, writing comes from a place beneath intellectual consciousness. The only way to get to that place is by writing. Trust the magic of that process.

- Be wildly ambitious about your writing, and forget the stuff connected to writing.To use a sports metaphor: keep your eye on the ball. Publishing is not the ball. Getting an agent is not the ball. Winning the National Book Award is not the ball. The writing is the ball.

- Spend a lot of time figuring out what your story wants to say.Then figure out who the central characters are that you need to visit.Then report the hell out of it. You have to research your own life. Go back to the old ‘hood; walk by your old house. You count the rooms, you eat the food, you drink the coffee, you sit in the bar, you go to the gas station and ask for directions. You have to breathe the air. Nothing might come of any of it, but you can’t train just one muscle. You have to train the whole body.

From WHY WE WRITE ABOUT OURSELVES: Twenty Memoirists on Why They Expose Themselves (and Others) in the Name of Literature by Meredith Maran, to be published on January 26, 2016 by Plume, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Meredith Maran.