essays

Jeff VanderMeer Explains How to Wash a Mouse in the Southern Reach

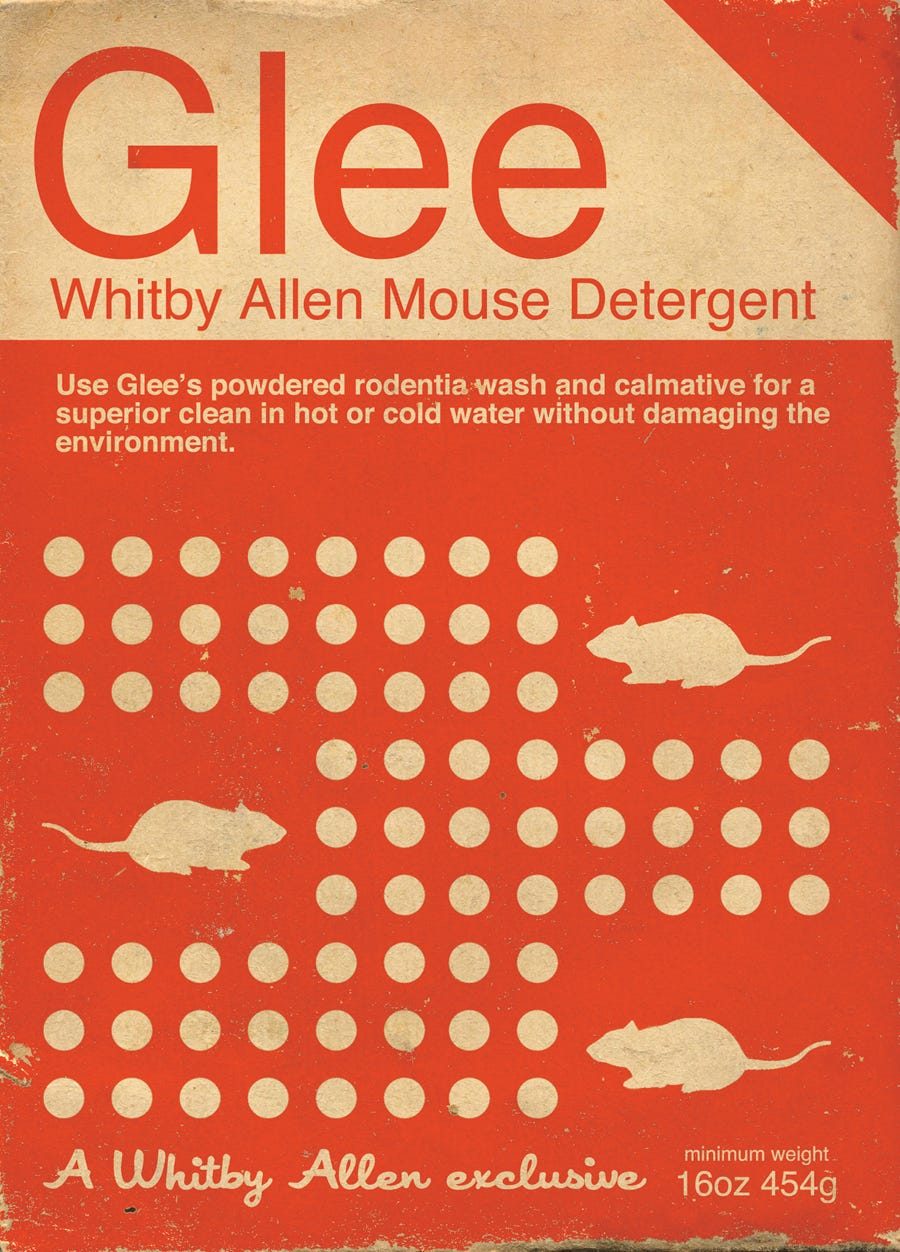

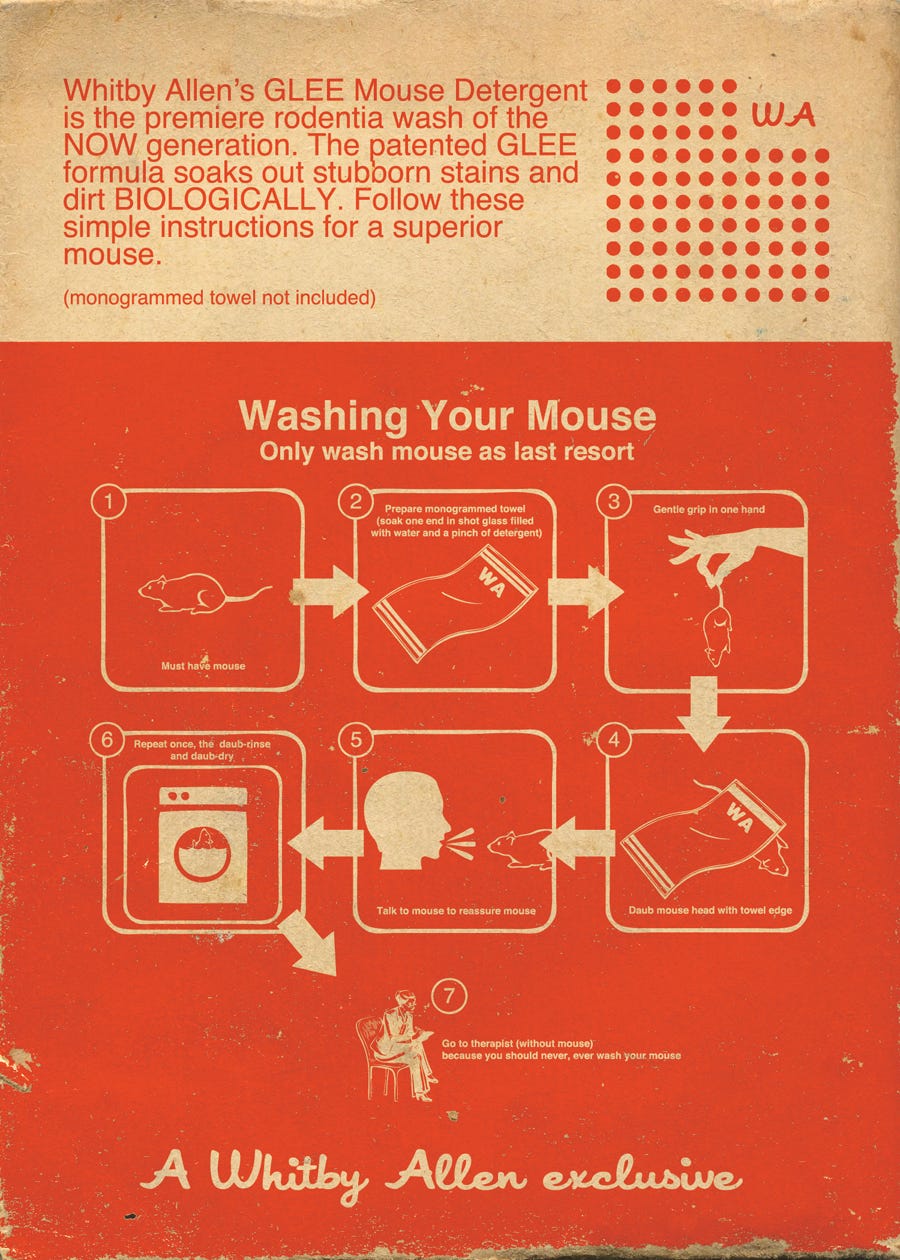

Today is the release date for Area X, the hardcover omnibus of Jeff VanderMeer’s best-selling Southern Reach Trilogy. All three novels (Annihilation, Authority, and Acceptance) are now collected in the single hardcover volume. To celebrate, VanderMeer has written about what one of the most uncanny scenes in the book: Whitby’s mouse washing. Below you will also find exclusive illustrations of Whitby Allen Mouse-Washing Detergent and an excerpt of the mouse-washing scene from book three, Acceptance.

One of the more intriguing characters featured in the Southern Reach Trilogy is Whitby Allen. At least, from my point of view in writing about him. Whitby’s a perpetual assistant to others at the Southern Reach secret agency. He’s obsessed with figuring out what’s going on in the mysterious Area X, like a lot of people at the S.R. But in his case, obsession has colonized him in ways it hasn’t the others. When readers first meet him in the second novel, Authority, it’s hard to get a bead on him. Someone once called him the “Smeagol of the Southern Reach,” and I can see that — in that you don’t know whether or not to find him sympathetic. As Authority progresses, the reaction from readers varies. Some find him pathetic. Others find him creepy. But once readers encounter him again in Acceptance, the final novel, it’s clear that he’s a good case for re-evaluation. If the novels have a recurring motion or sense of action, it comes from the idea of characters coming into contact with Area X, either for real or on an abstract level, and how that changes them.

A pivotal part of our understanding of Whitby, in my humble opinion, comes from a scene in Acceptance where Whitby washes a mouse. This is a mouse previously encountered in

Authority, and as with most elements of the first two novels, the mouse also gets re-cast in a different light by Acceptance.

How does one write a mouse-washing scene? There aren’t a lot of examples in literature, and in any event I didn’t want my mouse-washing scene to be contaminated by the work of other fiction writers.

How does one write a mouse-washing scene? There aren’t a lot of examples in literature, and in any event I didn’t want my mouse-washing scene to be contaminated by the work of other fiction writers. Especially since Whitby’s not exactly a standard character. But I knew props were important — the monogrammed towel fits with what we know of Whitby being both kind of finicky and coming from old Southern money. He might not be rich now, but the accoutrements of the rich would still surround him. Second, he’d be meticulous about washing the mouse. Third, washing the mouse would be hiding some other anxiety, would be a way of focusing that would, temporarily, wash away his stress. But also, hopefully, it would be a scene that would restore Whitby’s basic humanity — that would make the reader go back to Authority and read some scenes (like ones in strange rooms) a little differently. There are some other underlying thematic resonance to tidal pool scenes elsewhere in the novel and a few other things I wanted to accomplish, but I don’t want to tell anyone how to read the scene any more than I already have…

That said, there’s one problem with washing a mouse: You’re never supposed to wash your mouse. So when the brilliant designer Matthew Revert came up with a Whitby Allen Mouse-Washing Detergent after reading the novels, we had to add several disclaimers to the final images (unveiled here for the first time). So if there’s one thing I’d like you to take from this unveiling of the mouse-washing scene, it would be to please not wash your mouse. Never. No-how.

Whitby Allen: purveyor of strange rooms, the comic yet tragic Smeagol of the Southern Reach, and amateur mouse-washer. Enjoy.

– Jeff Vandermeer

An exclusive excerpt from Acceptance: the mouse-washing scene

One spring day at the Southern Reach, you’re taking a break, pacing across the courtyard tiles as you worry at a problem in your head, and you see something strange out by the swamp lake. At the edge of the black water, a figure squats, hunched over, hands you cannot see busy at some mysterious task. Your first impulse is to call security, but then you recognize the slight frame, the tuft of dark hair: It’s Whitby, in his brown blazer, his navy slacks, his dress shoes.

Whitby, playing in the mud. Washing something? Strangling something? The level of concentration he displays, even at this distance, is of working on something that requires a jeweler’s precision.

Instinct tells you to be silent, to walk slow, to take care with fallen branches and dead leaves. Whitby has been startled enough in the past, by the past, and you want your presence known by degrees. Halfway there, though, he turns long enough to acknowledge you and go back to what he’s doing, and you walk faster after that.

The trees are as sullen as ever, looking like hunched-over priests with long beards of moss, or as Grace says, less respectfully, “Like a line of used-up old drug addicts.” The water carries only the small, patient ripples made by Whitby, and your reflection as you come close and lean over his shoulder is distorted by widening rings and wavery gray light.

Whitby is washing a small brown mouse.

He holds the mouse, careful but firm, between the thumb and index finger of his left hand, the mouse’s head and front legs circled by this fleshy restraint, the pale belly, back legs, and tail splayed out across his palm. The mouse seems hypnotized or for some other reason preternaturally calm while Whitby with his cupped right hand ladles water onto the mouse, then extends his little finger and rubs the water into the fur of the underbelly, the sides, then the furry cheeks, followed by anointment of the top of the head.

Whitby has draped a little white towel across his left forearm; it is monogrammed with a large cursive W in gold thread. Brought from home? He pinches the towel from his forearm and, using a single corner, delicately daubs the top of the mouse’s head while its tiny black eyes stare off into the distance. There’s a kind of febrile extremity of care here, as Whitby proceeds to wipe off one pink-clawed paw and then the other, before moving to the back paws and the thin tail. Whitby’s hand is so pale and small that there is a sort of symmetry on display, an absurd yet somehow touching suggestion of a shared ancestry.

It has been four months since the last member of the last eleventh expedition died of cancer, six weeks since you had them exhumed. It has been more than two years since you came back across the border with Whitby. Over the past seven or eight months, you have had a sense of Whitby recovering — fewer transfer requests, more engagement in status meetings, a revival of self-interest in his “combined theories document,” which he now calls “a thesis on terroir,” evoking a “comprehensive ecosystem” approach based on an advanced theory of wine production. There has been nothing in the execution of his duties to indicate anything more than his usual eccentricity. Even Cheney has, grudgingly, admitted this, and you don’t care that the man often uses Whitby as a wedge against you now. You don’t care about reasons so long as it brings Whitby back closer to the center of things.

“What do you have there, Whitby?” Breaking the silence is sudden and intrusive. Nothing you say will sound like anything other than an adult talking to a child, but Whitby’s put you in that position.

Whitby stops washing and drying the mouse, throws the towel over his left shoulder, stares at the mouse, examining it as if there might still be a spot of dirt here or there.

“A mouse,” he says, as if it should be obvious.

“Where did you find her?”

“Him. In the attic. I found him in the attic.” His tone like someone about to be reprimanded, but defiant, too.

“Oh — at home?” Bringing the safety of home to the dangerous place, the workplace, in physical form. You’re trying to suppress the psychologist in you, not over analyze, but it’s difficult.

“In the attic.”

“Why did you bring him out here?”

“To wash him.”

You don’t mean for it to seem like an interrogation, but you’re sure it does. Is this a bad thing or a good thing in the progression of Whitby’s recovery? There is no base score assigned to owning a mouse or washing a mouse that can confer an automatic rating of fit or unfit for duty.

“You couldn’t wash him inside?”

Whitby gives you an upturned sideways glance. You’re still stooping. He’s still hunched. “That water’s contaminated.”

“Contaminated.” An interesting choice of words. “But you use it, don’t you?”

“Yes, I do . . .” Relenting, giving in a little, relaxing so that you’re less concerned he’s going to strangle the mouse by accident. “But I thought maybe he’d like to be outside for a while. It’s a nice day.”

Translation: Whitby needed a break. Just like you needed a break, pacing the courtyard tiles.

“What’s his name?”

“He doesn’t have a name.”

“No.”

Somehow this bothers you more than the washing, but it’s an unease you can’t put into words. “Well, he’s a handsome mouse.” Which sounds stupid even as you say it, but you’re at a loss.

“Don’t talk to me like I’m an idiot,” he says. “I’m aware this looks strange, but think about some of the things you do for stress.”

photo by Kyle Cassidy

Jeff VanderMeer’s most recent fiction is the NYT-bestselling Southern Reach trilogy (Annihilation, Authority, and Acceptance), all released in 2014 by FSG Originals and also acquired by publishers in 17 countries. The movie rights to the series, which features strong ecological themes, were acquired by Paramount Pictures/Scott Rudin Productions. His Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction (Abrams Image) is taught widely. His nonfiction, much of which pertains either to the environment or to weird fiction, has appeared in the New York Times, the Guardian, the Washington Post, Atlantic.com, and the Los Angeles Times.