essays

Liar, Liar: On Writing About Rape Online

I never meant to become a woman who writes about my rape on the Internet. I didn’t mean to be raped, I didn’t mean to not get over it, I didn’t mean to go to grad school for creative writing and immediately begin writing about rape instead of the things in my application, I didn’t mean for that first rape essay to feel urgent and necessary, and I didn’t mean to feel a need to send it out only to places that would publish it online. But once I had put all of it in motion and the essay was published, it went well. It felt cathartic. The Internet treated me nicely. Other than one semi-negative comment (which the site that published the piece took down), it was all pretty pleasant. Nobody wrote hate-filled emails or mean tweets about me. When I posted the link to my essay on Facebook, my friends and family were overwhelmingly supportive.

In some ways, it felt as though the trauma of rape had fizzled out and been replaced by the warm fuzzy feeling of doing something good. Women I knew or barely knew or didn’t know at all messaged me to say they too had been raped, and that my writing was helpful to them. A woman whose daughter I knew in high school messaged to say she had finally decided to break her silence. Other writers sent me friend requests, posted my essay on their pages. Writing about rape on the Internet seemed, for about nine lovely months, like a thing that would not have consequences for me.

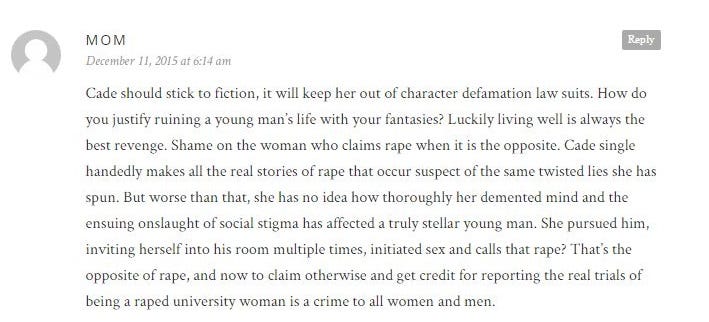

Until last week, when my rapist’s mom found an essay. I say an essay because the first essay (“the big one,” in my head, both in terms of disclosure and sheer length) became two and then three and then four essays on three different sites, plus a post on my blog, plus a pretty open social media survivor presence. But of course it was that one, “the big one,” that she found. And she had some things to say.

It would be an exaggeration to say my world collapsed when I found that comment. But it would be true to say I became briefly stuck to my computer. For about four hours I didn’t move. I stared at the screen, read and re-read her words, I thought about whether “Mom” really meant his mother. I thought about how specific her version of the story was. I imagined him telling it to her (in her house, at the kitchen table, over the phone, in a text message). I called my loved ones to ask for advice. I screencapped the comment. I asked the site to take it down, they responded quickly and it disappeared. I posted on Facebook about the whole incident. And then I sat some more. And stared. Kept staring. There was no more active evidence that the comment had ever been there. It got dark out. I was going to be really late to a friend’s birthday party if I didn’t just shut my computer and fucking stand up. I really needed to pee. I stayed a little bit longer.

For at least three years, since before my rapist went abroad for our junior year of college, I have heard nothing from him. In the year he was gone, I did what I could to heal. Senior year, when he was back and I saw him around campus, I went out of my way to avoid him. I tried to make myself invisible. And, for a while, I thought I was fine.

Then I graduated and moved a few states away and suddenly found that every time I opened up a new document, all I could do was write about rape.

But I think what makes me angry, so specifically angry at him and at his mother (or him posing as his mother, which might be worse) in this moment, is that in that essay where I decided to make myself so very visible, to name myself and to unveil whatever insecurities and fears and embarrassments I could at the time, I took pains to make him invisible. My rapist is barely a character in my essays. He is never named, he is never given characteristics (height, race, hometown, likes and dislikes, names of his friends, college major). The most I’ll say is that my rapist and I lived on the same hallway in the same dorm for a year.

So why was he so pissed off? Why did he tell his mom about it? And why did he tell her how to find me? It’s been five years since he raped me. I didn’t report it at the time, so I don’t name him now. In a way, I erased him. I became the writer with the power, with something to lose.

I try to not write the scene of rape…in my experience, when people are doing the thing I refer to as “finding the lie” in a rape story, they look to that scene.

Recently, I was on a panel (“Grad Feminist”) at my undergraduate institution. The panelists were asked what we do to protect ourselves from online hate. When it was my turn to answer, I said I try to not write the scene of rape. I said that in my experience, when people are doing the thing I refer to as “finding the lie” in a rape story, they look to that scene. They’re looking for moments where they can say “oh, well that was consent” or “well you moved your hips like that” or “you shouldn’t have said x, you should have said y” or “and you didn’t scream?” I wanted to give them none of those moments. I still am not writing any rape scenes. But it didn’t, doesn’t, matter to him that I avoid specifics, if I avoid the physicality, if I avoid the stupid detail that when he pushed me down onto his bed, my ankle scraped against the bedpost and the skin peeled off. As if either of us should care about one, small, almost unrelated injury. It was still not enough for me to be quiet about all of that. Because in his version, my whole truth is the lie to find.

So rapist-person, B-, hi. Did you tell your mom that you raped me on my third day on campus? Did you tell her about the time you admitted it to another hallmate, did you tell her about the time our sophomore year when I saw you at a party and we were both drunk and you asked for my forgiveness? You might have told her I said I forgave you, because I did say that. I was nineteen and it seemed like the easy answer. It made you smile. Afterward, briefly, you seemed less dangerous. Then I heard from a friend that you had behaved threateningly toward another woman after she rejected you. Then I remembered who you are.

I was talking about you the other day on the phone to my dad and I said, “I hate him!” as if it was a new thought. Though I guess I haven’t hated you in a while. I don’t know if I really hate you right now. I hate rape culture. I hate what you did. But you’re not a monster, you’re a human. You have flaws and skills and friends and teeth and a tube of superglue in your desk drawer, just like the rest of us. I don’t think I can hate a human being, even if I can say that I do. What I mean is I thought you’d left me alone or I hope you haven’t hurt anyone else or please don’t come back to haunt me, I thought I was safe. You broke some of that self-care (self-instruction, self-love, self-control) just now. Or your mom, or both of you, or a stranger, somebody knocked me briefly back into hate. I’m inclined to think it’s you, though. Five years later, you are still so good at breaking things. Five years later, I am still getting used to putting myself back together.