interviews

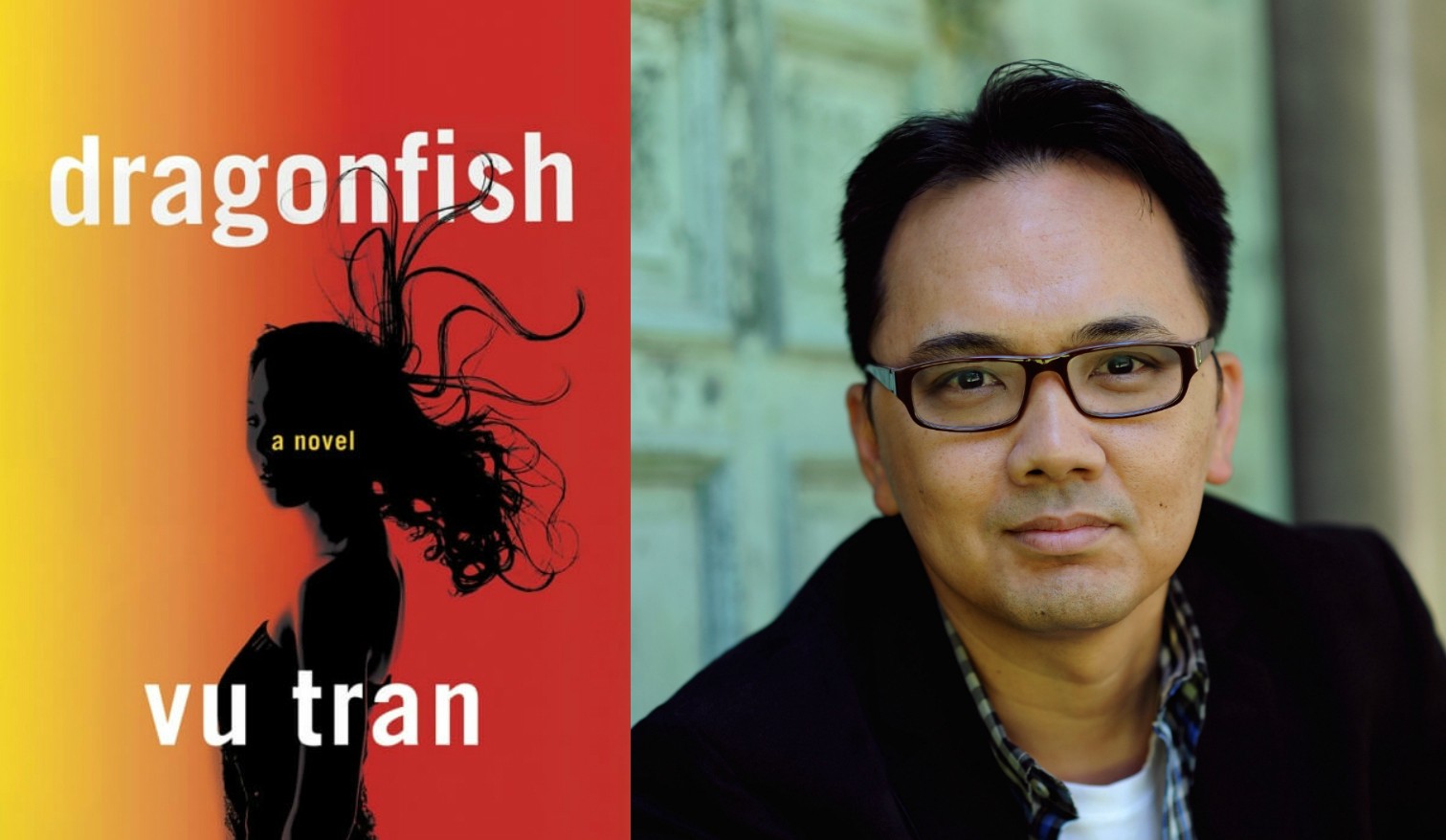

Like Drilling For Water: Finding The Universal With Ron Rash, Author Of Above the Waterfall

Ron Rash was born in Chester, South Carolina and has made a career of writing powerful works set in this region of the United States. Many have labeled him a Southern writer or an Appalachian writer, but those terms are deceptive. Rash’s characters are certainly connected to their landscape, but, as with any work that transcends, Rash brings the reader to the universal human concerns inside the particular details.

Rash has published over a dozen books of poetry, short stories, and novels, earning several awards and twice being selected as a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. Above the Waterfall (Ecco 2015), published this September, is his sixth novel.

In Above the Waterfall, we follow two protagonists with traumatic pasts. Becky, now a park ranger, was the child who spoke while her class was hiding from a shooter in her elementary school, and she blames herself for the shooter discovering and murdering her teacher. Les, a sheriff just shy of retirement in a community dealing with a meth epidemic, had a marriage fall apart after telling his suicidal wife, in a moment of frustration, to just kill herself.

I had the chance to sit down with Rash for a while before a recent discussion he had with Richard Price at the McNally Jackson bookstore. The store clerk set us up with some stools in the poetry section of the store, as, alas, this was the place where we were least likely to be disturbed by a customer (we made a point of encouraging any potential supporters of poetry to browse if they approached during the interview — as Rash, a poet himself, observed, “we need all the help we can get!”). We talked about life in the mountains, the depiction of meth on television, and Rash’s fascination with the Lascaux cave paintings, as well as why literature is more important now than ever.

CL: For better or worse, people like to put labels on things, like “Southern literature.” What does that term mean to you?

It’s almost like a form of drilling for water; you go deep enough into a place, and you’re going to hit the universal, because you’re hitting what’s true of people.

RR: I’m ambivalent about it. On the one hand, I certainly see myself as part of that tradition of writers, such as Welty and O’Connor and Faulkner. They have been very important to me and have shown me I can write about this world — not that they’re the only ones who’ve shown me. But I worry sometimes that there’s another adjective in front that says “just” Southern literature. To me, what makes Faulkner and O’Connor such great writers is that–even though they are very much about place, in the tactile way they describe it–what makes them significant is not that they are writing about the South. It’s that they hit the universal. Faulkner is revered all over the world, and it’s not that he’s just writing about Southerners. He’s writing about something that is true to being a human all over the world. And that’s the Southern writer I identify with, not the one who says, “Lookit, Uncle Jesse got et by the hog,” or something that that. The difference to me is the difference between being a regional writer, in the sense that James Joyce is a regional writer, and being a local color writer. A local color writer is all about what makes a place different or distinctive. A regional writer does both: shows what’s distinct in the manners, customs, language–and I love that, writers love that, readers love that, too–but ultimately it’s all in an attempt to find the universal. It’s almost like a form of drilling for water; you go deep enough into a place, and you’re going to hit the universal, because you’re hitting what’s true of people.

CL: It’s interesting that you mention drilling for water. Water is so important in your work and in this novel, Above the Waterfall.

RR: Oh, yeah, for a number of reasons, such as the mythological force of water as destructive and life-giving. I’m also fascinated with the Celtic view of water being a conduit between the living and the dead. Not so much in this novel, but in my second novel, Saints at the River.

CL: The landscape and the place (Appalachian mountains) seem central to your novel Above the Waterfall. Could this story really exist anywhere else?

RR: The locale and the landscape are important, I don’t want to say that they’re not. They’re crucial. I’m fascinated with how landscape affects psychology. Mountain people I think have a different perception of reality, than opposed to, say, someone who lives in the Midwest.

CL: What’s the mountain person’s perception of reality?

RR: I’ve heard this from readers from around the world, whether it’s the Andes or the Alps or the Himalayas: people who grow up in a mountainous landscape have two tendencies–one positive, one not so positive. The positive one is a sense of being protected in the world, almost nestled in this place. The less positive is the sense of constantly being reminded of your own smallness and brevity in the presence of these mountains that are constantly looming over you, even to the point where sometimes it’s not just psychological but physiological, in that not as much sunlight gets through. I think Gatsby had to be a Midwesterner because he sees the world as, ‘anything is possible.’

CL: I have read that you don’t start with an outline when you write. You never have?

RR: Well, I did when I wasn’t writing well! I remember when I first started writing stories, I always knew what was going to happen, and what it was “about,” and I’ve just become pretty much convinced that the worst thing a writer can have, or at least that this writer can have, is an idea.

CL: Why is that?

RR: Because suddenly you’re thinking of it not only in an abstract way, but you’re also limiting it, it’s going to be about “this.” And to me, the wonderful thing in my books is that I don’t know. I kind of let it reveal itself.

CL: There is a line early on, not technically the opening line, but close, that asks, “Where does any story really begin?” Where do your stories begin?

RR: I start with an image. Every book I’ve written, every novel, has started with a simple image. In this one, it was a stream with dying trout in it. I didn’t know why they were dying. I had a sense, but that’s where it started.

CL: So is this an image that you’ve actually seen?

RR: Well, it’s not a memory. When I wrote Serena, when that novel began, all I had was an image of a woman on horseback, and from her posture I knew she was formidable. But that was it.

CL: Where does the story end?

RR: That is always the question!

CL: Where did this one end?

RR: As I got deeper into this book and I knew the characters better, I knew that it would end with some kind of redemption for both of them [the two main characters, Les and Becky]. And I didn’t know this at first, but ultimately I realized it was going to be a book that was about two people who had said words that had caused terrible things to happen, or almost happen. Becky speaks because she’s frightened in the basement, and she blames herself. And Les has spoken these words that causes his wife to almost kill herself. It became a book about, how does one live in the world [after these experiences]? Les has to look at the worst in the world, as a way to exonerate himself. Becky has to look for hope in the world. That’s who she is. To me, it’s a novel of people who are finding some kind of redemption.

CL: In this novel, you go back and forth between two first person narrators, Les and Becky. Did you start with one narrator, or was it always going to be two? Can you tell me about that choice?

RR: I had a lot of trouble with this book. It was supposed to come out last Fall. What happened was, I knew the book wasn’t ready, and so what I did instead was I pulled the book. Up until that time, Les had been the only narrator, and I knew something important was missing. It was Becky’s voice; once I locked into that voice, I knew I had the answer. And then it just became a matter of establishing, I hope, like a musical score of the intense language of Becky and the prose sections of Les. I wanted a sense of Becky’s immediacy to the world, so everything she says is in present tense, and Les is in past tense, except for the last sentence. It was just a matter of discovering that, and to realize how crucial her voice is. And it also gave me a chance to use what I’ve learned writing four books of poetry, to try to create a language as intense as I could.

CL: Becky writes poetry, and some of her poetry is in this novel. Can you talk about the fact that you write poetry and short stories and novels, and how those forms speak to each other when you are writing? How did the process of writing poetry into this novel work for you?

RR: Having written poetry and reading so much poetry makes me a better fiction writer. In my last couple of drafts it’s all about rubbing vowels and consonants together, and playing off the rhythms, and stresses and unstresses. It’s not that the reader will necessarily notice that, but the ear will.

CL: Do you think about your readers reading your work out loud? I mean, poetry is often meant to be read aloud. Do you hear the words as you’re writing? Is part of your writing process to read your work out loud?

RR: Yeah, I get so into the voice that I hear it. I wouldn’t necessarily read a couple of pages to myself aloud, but I will, if there’s a sentence or two that’s not working, I’ll say it aloud, and almost always my ear will catch the problem. The ear knows before the eye.

CL: That brings me to another question about the influence of other media. Your character Les paints, or he did paint up to a certain point. Do you work in any other media yourself, besides writing? Is your writing inspired by other media, maybe music?

RR: Yeah, music definitely. One of the great gifts my generation got–I’m 61–is we listened to all that rock and roll. Listening to all that music growing up, even though it was rock and roll and country, you’re immersed in that music, and some of that has to rub off on your writing. And my father was an art teacher. Actually, my middle name is Vincent, because of van Gogh, and I mention van Gogh in the book. I have no talent for it, but I try to bring what I’ve learned, in a way, from painting into words, in a scene or a paragraph, where I’m trying to show it as intensely as possible, as vividly as possible.

CL: It’s interesting that your father was an art teacher and you have two main characters, one of whom paints and one of whom is a teacher, in a way, to children. I noticed in this book that there is a lot of reference to children: babies who are in danger, or people who go on to have children with others, and so on, but your two main characters don’t have children. I wonder about that, if that was a choice you made for a particular reason?

I’m unhealthily solitary. There are days I write more words than I speak.

RR: It was, yeah, because I wanted these characters to be as isolated as possible. That’s their attraction. When they see that Hopper painting [in Les’s office], they recognize that sense of being alone; that is their nature. I think part of that is what’s happened to them, but it’s also their very nature. And I’m a lot like that. I’m unhealthily solitary. There are days I write more words than I speak.

CL: I don’t think you’re alone in that. I find it curious that Hopper is this quintessentially American painter, and the people in his paintings are so very alone.

RR: Yeah. I remember the first time I saw Nighthawks. I was in fifth grade, and that thing just stung me. It was a reproduction at a library, and I was just transfixed. And part of it was that I was recognizing something that I sensed about me.

CL: In Above the Waterfall, the meth epidemic has a big impact on several people’s lives. There is a line: “Television glamorized meth, even when they tried not to.” A lot of people were introduced to meth culture in America via the television show Breaking Bad. Is that a show you watched, and do you have an opinion on it?

RR: Yeah, and that’s what bothered me. I’m not saying it was their intention, but I think what happens is, when you concentrate on the people who are manufacturing it, there’s always going to be some kind of charisma. Even if you make them monstrous, they have some kind of charisma. And what I do, is I focus on not just the victims, but also the people around them, like the parents. That’s the way you get rid of the allure.

CL: You also talk about the smell of meth. That is something that of course you don’t get through a screen. It’s something quite powerful that you can get while you’re reading. Did your preparations for writing Above the Waterfall involve researching people who suffer from taking meth, or the families who are affected?

RR: I’ve known families who have been devastated by it. A friend of mine actually died a few months ago. He was a sheriff’s deputy; he did these raids. He was the one I talked to. But that only takes you so far. You have to get to that point as a writer where you feel like you can get a sense of it through empathy. I didn’t base [the meth raid scene in the novel] on anything he told me — those are places where my imagination took me.

CL: All of your major characters have some kind of moral ambiguity or at least a hint of a possibility of moral ambiguity. Were any of the characters screaming to go more good or evil for you? Was it hard to achieve a level of moral ambiguity with any of them?

RR: I think that politics gives us the black and white, and art gives us the gray. I think most people are a mixture of those things, and a character isn’t going to be very interesting if it’s either/or. There is always complexity, and the ability to give the reader a sense that there is always something you don’t quite know. I learned this from Shakespeare. Something Shakespeare does with his characters that’s pretty important is about motivation missing, and I think that makes characters much more interesting.

CL: Motivation missing?

RR: Yeah, I think [in good writing] there’s always something we don’t quite know, because I think that’s true in life. We think we know someone, but there’s always something we don’t quite know.

CL: Was it reading those works by Shakespeare that got you into writing? What prompted you to become a writer?

The books I love, I feel that way–they enter me

RR: I always loved reading, but as I’ve told people before, when I was 15, I read Crime and Punishment for the first time, and obviously I wasn’t getting a lot of what was going on, but that scene where the pawnbroker is killed, I remember, I can tell you exactly where I was when I read that. It felt like an out of body experience. I felt like up to that moment, I had entered books, but that book entered me. The books I love, I feel that way–they enter me. And even if I wanted to, I couldn’t forget it.

CL: Are you reading when you’re deep into writing a novel?

RR: Yeah. There are certain writers I avoid because their style is so powerful, but I just love to read. I’m actually reading Knausgaard’s My Struggle right now. I love it. And I went in thinking I wouldn’t, thinking, okay, well, here’s another self-indulgent…but it wasn’t. He does this thing where he won’t let you stop reading. I think Hilary Mantel has that. And that’s something that can’t be taught, you either have that or you don’t.

CL: So are you losing sleep needing to read more Knausgaard?

RR: Actually, what I’ve been doing is, I exercise every morning for 50 minutes on an elliptical, because I can read. I actually read it this morning. So that way I get in an hour of reading every day, at least. Because once I start my 6–8 hour day of writing, I’m pretty burned out by the end. All I want is wine and ESPN.

CL: Many writers say they have to get their writing going at the beginning of the day, because if they do something else all day and then try to get their brains going at night, it’s hard.

RR: I can’t do it. This morning I wrote for 2 ½ hours. I just got up, did my exercise, and wrote for 2 ½ hours.

CL: Do you write every day?

RR: Yeah.

CL: Every day?

RR: Yeah, I mean some days I tend to do a little less, but even on Sunday I write an hour, sometimes five or six, it depends.

CL: And you’re teaching, too?

RR: Not this semester. But I do teach.

CL: How does teaching play into your writing?

RR: I would not want to be someone who all I did was write, because it goes bad too many days. If, say, I have a week where I have three or four days where the writing is absolute crap, I can at least say I met this class, I got this student turned onto this writer he or she has never heard of, and maybe I’ve passed something on that’s going to help this person, if not as a writer, at least as a reader. And it gives a little bit of structure, and my whole life doesn’t depend on what I put on the page today–and that makes a difference!

CL: Your characters are so connected to the landscape and nature in Above the Waterfall, but there are also some notable mentions of technology and computers. There is a quote by one of your characters I wanted to ask you about: “In five years people won’t even know they’re in the world, much less care about what happens to it. They will believe that when everything else on this planet dies, they’ll be able to disappear into a computer screen.” What’s your own relationship to technology? How do you deal with the distractions of technology? Do you write on a computer?

RR: I write the first paragraph with a pencil and paper and then I type it in. But yeah, I do use computers, and, I mean, they’re wonderful. I’ve got this chapter here and it doesn’t go and I can move it…when I think about somebody like Faulkner and his little typewriter, I think, how the hell did he write anything? But one of the dangers for me with a computer screen is it looks too good too quick. I always run it off. I want it to be messy. I don’t edit on a screen. But I do worry about what technology is doing to us. What strikes me is, it seems we are almost getting to a point where we don’t think something is reality unless we see it on a screen. There is this point in the book where Becky talks about people coming out and taking pictures — they can’t even see the nature, they have to see it on a screen.

CL: And maybe share it.

I would argue serious literature is more important than it’s ever been, because it’s an escape…into complexity, into attentiveness

RR: Yeah, I mean that’s the implication, instead of connecting to this thing. I really worry about the distractions and attention spans. If people don’t have attention spans, then they are so much easier to manipulate, because then it all comes down to sound bites. I would argue serious literature is more important than it’s ever been, because it’s an escape from that into complexity, into attentiveness that is not 10 or 15 seconds. The little house where I live in the mountains, I can’t get email. And most of the time when people try to call me by cell phone, they can’t reach me.

CL: That sounds glorious!

RR: Yeah, people say, does that bother you? Hell no. I mean, I get email in my office. But even I admit, it’s so addictive. I’ll notice that if I’m not careful, I’ll start checking my email every 15–20 minutes.

CL: Why do you think it’s so addictive?

RR: It’s almost like a kind of candy, a little treat, a little sugar treat. Always that idea that this next email is going to be from the Nobel prize committee, or that girl I really like, whatever. But at the same time, what I love seeing in my students is this sense that, damn, there’s something happening here reading this book that I’m not getting anywhere else. And that’s what I love about the Harry Potter series for kids. I think one of the great things about that series is it showed kids there’s something a book does that nothing else can. What I love about reading a really good writer, is that it’s an act of communion. I mean, you’re communing with someone who’s probably a lot smarter. I’m communing with say, Edna O’Brien or Stendhal or whoever. Because all writers just give us a splotch of ink and so we have to build this together, we come together on this thing. I find that incredibly magical. A good reader has imagination, you have to have imagination to put that together. It teaches imagination.

CL: I have to ask about the Lascaux cave paintings. They come up throughout Above the Waterfall, and even open the novel–a book about the paintings is the only book that Les borrows from Becky. And Becky is creating a new language, just as the Lascaux cave paintings were creating a new language.

RR: Personally, I’ve always been fascinated with those paintings. I’m about to go to France, and I don’t think I’m going to have time to get to the caves, but have you ever heard of Jerusalem Syndrome? People get so overwhelmed they lose it and start thinking they’re Jesus? If I go in those caves, there’s a part of me that thinks I’m going to go completely crazy, because I’m so intently drawn to the idea of this, I wouldn’t say pre-conscious, but there’s something going on there…I mean, those animals, they look like they’re moving when you use torchlight. What makes it fascinating is the animal dominates that inner world… Jung, that was his great big dream, you just go into the end of that collective unconscious. I’m very much a Jungian. I believe in that kind of thing. And Becky, what she wants is that total connection to “world” and “word” and “wonder,” those three things, because she was so shattered when she was twelve, and she sees it in the Lascaux cave paintings.

CL: Do you think that you would ever move away from the area where you live, the Appalachian mountains?

I’m a writer who has to stay. I have to be connected to that landscape.

RR: I think a writer from the South, or anywhere outside a major metropolitan area, has to make a decision: do I have to stay here to write about this, or do I have to leave? Tennessee Williams, Capote, Carson McCullers–they all left. Faulkner, Welty, O’Connor stayed. I’m a writer who has to stay. I have to be connected to that landscape. Being connected to it makes it better for me as a writer. But the other thing is, it can hurt a writer as far as career to be in a rural place. You don’t meet the people at the parties, but [at those parties] you also lose a lot of time and energy that you could be writing. So I made the choice to stay, but the way political things are going now, if I were ever tempted to leave it would be now.