Books & Culture

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: Everything is Illuminated — The New York Antiquarian Book Fair

L

Each month in the Literary Artifacts space, writer Kristopher Jansma writes about his encounters with rare books, writerly memorabilia, and other treasures in New York City and around the world, hoping to discover how the internet age is changing the face of literature as we know it.

Recently I dropped by the Armory on 67th and Park Avenue in Manhattan to see the 52nd Annual New York Antiquarian Book Fair and some of the rarest books on Earth. The fair brings booksellers from around the globe together with wealthy collectors and those, like me, who just want to breathe in the smell of hundred-year-old paper.

Actually I was sniffing around for something else. This was the same week that the Department of Justice’s suit against book publishers was announced and apocalyptic sentiments seemed to be in every newspaper, blog, and morning show. The enormous, austere Armory space on the Upper East Side, “one of the largest unobstructed spaces of its kind in New York,” seemed like a good place to get a bit of perspective. At the very least I thought I might hide amidst the most valuable books I could find.

Swiftly I moved past all the old maps and important letters — and came directly to a glass display of hardcover novels. Rare first editions of The Sun Also Rises and A Light in August sparkled in their protective plastic. Each was worth about $1000 — or a month’s rent, to my mind. They seemed almost a bargain compared to the first edition of The Maltese Falcon, selling for $25,000. Sure, it was signed by Dashiell Hammett to Bebe Daniels (who starred as femme fatale Miss Wonderly in the 1931 film adaptation), but $25,000 for a book? I love books as much as the next guy — often times much more than the next guy — but at the end of the day it was still just an arrangement of paper and glue and ink, right? Not a subcompact car, or a down payment on a starter home.

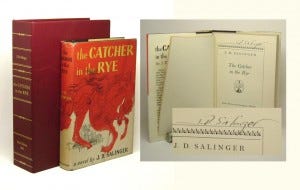

But even $25,000 seemed cheap by the time I got to the neighboring Baumann Rare Books booth. There I saw a first edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass going for $165,000. “If you think that’s a lot,” the man there said, “check this out.” And then he pointed to — of all the rare books on the planet — the one I’d most love to own myself: a first edition, first printing, signed copy of The Catcher in the Rye. And it could be mine for just $186,000, or the entire college tuition of my as-yet-unconceived firstborn child.

While I silently reeled from sticker-shock, a collector next to me scoffed. “It’s not even in good condition! You could get an illuminated manuscript over there for less than that.” He thumbed towards several bibles from the 14th century, written in cryptic languages.

Suddenly I began to think that perspective was the last thing I’d be finding at the Armory.

The seller at Bauman Books informed me that the age of a book does not solely determine its value. While his was one of only two signed first editions known to exist, even an unsigned first edition of Catcher sells for around $16,000 because the first edition was the only version of any J.D. Salinger book to ever be printed with his photo on the back. His signed edition becomes rarer each year that 65 million fresh copies of The Catcher in the Rye are sold to high school students worldwide with no image of the author at all.

This made me think of Clearwater High in Florida, which this year ditched their printed Catchers and mandated that students read on Kindles. Would the dog-eared paperback I’d stolen from my own high school thirteen years ago soon become the rarity? Would my children’s children look at it like I’d looked at the illuminated manuscript: just an indecipherable relic?

Next I stumbled across Ken Lopez Books, which had a selection of more recent authors like Douglas Adams and Kurt Vonnegut. In fact, their collection was so contemporary that for $350 they were selling a manuscript copy of Dave Eggers’s as-yet-unreleased novel, A Hologram for the King. I thought about asking to look at it, but it felt a little like digging through a neighbor’s trash. Instead I looked longingly at a signed copy of Girl with Curious Hair by David Foster Wallace for $600, and wondered how much the price had increased after his suicide. If only I’d bought one a few years earlier, I found myself thinking — and soon felt even worse. Being a rare book collector was beginning to seem as callous as placing bets on one of those celebrity death-watch websites.

Hoping for some cheer, I wandered over to the booth for Books of Wonder, with its bright collections of rare Wizard of Oz books. Beneath these I saw a signed first edition copy of The Hunger Games for $1750. When I asked the man there exactly what made this book from 2008 so valuable already, he explained that The Hunger Games had had a small first run and not been popular right away. Now it was popular and the value was up. Plus the author, Suzanne Collins, had suffered a hand injury while writing the second book, and so now could only stamp readers’ books with ink, thus driving the value of a real signed copy even higher. $1750 was a bargain, he explained. If my great-grandparents had scooped up a signed The Wizard of Oz a hundred years ago, I could practically retire on it today. So the gamble really came down to a bet that my future children would be reading the imaginative post-apocalyptic tale in fifteen years, and that their own children would be reading it in another thirty.

But of course, in my own post-apocalyptic imagination, I am still afraid that by that time all printed books will be as rarified as the ones at The Armory. Already my children might be required to do their summer reading on a Kindle, but will I have to drive to Manhattan to take them into a real bookstore? Twenty years ago, when I was a kid, I could ride my bike to Lincroft Books, just up the street from my house. Then the Barnes & Noble all the way out by the mall drove them out of business. Now I’d be grateful even for the B&N.

And what of the books themselves? Amazon’s growing digital direct model promises to connect writers directly with readers, bypassing the publishing “middle men”. But without Hemingway’s editor, Max Perkins, would The Sun Also Rises hold up after almost 90 years? Would The Maltese Falcon ever have been written if not for H.L. Mencken’s Black Mask magazine? Editor Gus Lobrano had to practically keep J.D. Salinger on life-support in the New Yorker for months before The Catcher in the Rye was finished. And today’s editors are no less vital to the process. Kate Egan and the good people at Scholastic worked with Suzanne Collins for years as she developed The Hunger Games. David Foster Wallace, in his book-length interview with David Lipsky, goes on for hours about the deep debt he owed Little, Brown for taking a chance on Infinite Jest. His editor Michael Pietsch made him cut 700 pages from the original manuscript, for which I think we can all be grateful. We can easily recognize writing which has been shoddily edited, but when it’s done well, we can see no fingerprints left behind. An editor’s job is to be invisible, to enhance a book without disturbing the voice of the author, and they rarely get recognition for the miracles they perform.

As I continued to wander through the Armory show, looking at all the astronomical price tags, it was hard to remember that at one time these books cost only a few dollars. If, in 2008, I had bought a copy of The Hunger Games for $25 and liked it enough to go to see Suzanne Collins at a signing, then today that small bit of enthusiasm would have amounted to a 6,900% gain on my initial investment. Of course very few books increase in value quite so dramatically, and many are worth only pennies if resold to The Strand a few months later. But it is still a reminder that when we pay $25 for a new hardcover, we’re not just buying a few hours of diversion, enlightenment, and conversation. We’re not just buying something that will spur our imaginations long after it has been placed on the nightstand. We’re not just buying the end-result of months or years of journalism and research and imagination. (Though if you ask me, $25 is a steal for any of these things). We’re also buying something that we can hold onto. A physical book has a value that can increase over time, because we can pass it on to our children and they to theirs. You cannot deliver a digital file back into the hands of its own creator for a signature and a personal note of thanks.

Certainly there’s plenty of praise due for eBooks, which have allowed huge audiences to return to daily reading. Not everyone is as sentimental about their books as I am, and not every book is going to be worth keeping for a hundred years. Indeed, I can feel the squeeze each time I try to cram another one onto my overloaded shelves. But we should also have the option of spending a little more on a keeper.

Finally, consider this. That $186,000 copy of The Catcher in the Rye would have cost a reader in 1951 about $3.95. According to The Awl, if you take inflation into account, this would be the equivalent of about $34.37 today. This means that a new hardcover book today is actually already cheaperthan it has ever been. A cent-by-cent breakdown by Motoko Rich at The New York Times shows that of the $25 you spend on a hardcover book, only about $3.25 goes into the physical printing, storage and shipping. When a publisher has to sell an eBook for just $9.99, the missing $11.76 gets covered either by paying authors less, or slashing editing and marketing budgets by nearly half.

I stopped by the copy of The Catcher in the Rye to say goodbye and took one last look up at the soaring space around me. The brochure I grabbed by the exit described the mission statement of the foundation that supports the Armory: its one-of-a-kind art and fashion shows and the various artistic fellowships that they give out each year. “Part palace, part industrial shed, Park Avenue Armory fills a critical void in the cultural ecology of New York by enabling artists to create, and the public to experience, unconventional work that could not otherwise be mounted in traditional performance halls and museums.”

The Armory itself is a reminder that great art requires all of our support. We must continue to make a space in our culture where such things can be staged, or we will soon find the place that art has always filled within ourselves conspicuously empty.

***

– Kristopher Jansma is a writer and teacher living in Manhattan. His debut novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, will be published by Viking Press in 2013. He has studied The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University and has an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University. He is a full-time Lecturer at Manhattanville College and also teaches at SUNY Purchase. Recently, his short story “A Summer Wedding” won 2nd prize in The Blue Mesa Review’s 2011 Fiction Contest, judged by writer Lori Ostlund. His essays and fiction can also be found on The Millions, ASweetLife.org, The 322 Review, Opium Magazine, The Columbia Spectator, and The (Somewhat) Complete Works of Kristopher Jansma. You can also find him on Facebook.