Books & Culture

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: The Ginsberg Collaborators

On a Wednesday night late in January, half a dozen known-associates of the late activist-poet Allen Ginsberg gathered at the Housing Works Bookstore on Crosby Street to read anti-government poetry and perform live, radical music to a room packed by dissidents both young and old, who were quite literally hanging from the rafters. It wasn’t so much an anarchistic rally as it was an exuberant and peaceful celebration of Ginsberg’s life in poetry and song. But it was hard not to be stirred by the lawless spirit of the Beats while in the presence of some of Allen’s greatest collaborators

Allen Ginsberg is best known as the poet who wrote “Howl” and as a member of the Beat Generation, friend to Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Neal Cassady, and Gary Snyder. It is these years of his life and these friendships which are most often the focus of today’s films (including the new Kill Your Darlings, starring Daniel Radcliffe, as Allen).

But long after those heady days, Ginsberg continued to collaborate with other writers, poets, musicians and luminaries. At the website for the Allen Ginsberg Estate, you can see photographs of him with Thelonious Monk, Patti Smith, The Clash, John Cage, Arthur Miller, William Gaddis, Susan Sontag, David Letterman, and even, well… Beck.

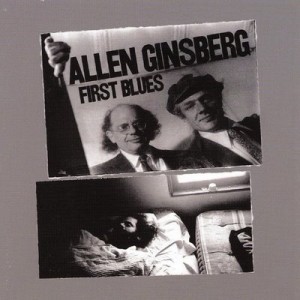

The January gathering at Housing Works launched the re-issue of Ginsberg’s album First Blues, and featured live performances by friends of Ginsberg’s who worked on the original album. Lou Reed and Bob Dylan couldn’t make it, but there were performances by poet Andy Clausen, composer David Amram, Anne Waldman (who, with Ginsberg, founded the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Colorado), and author Hettie Jones.

The record re-issue is part of a collaboration between Peter Hale, manager of the Ginsberg estate and Nina Kossoff, of Esther Creative Group, a music management company. Kossoff, who studied literature in college, jumped at the opportunity to work on something a bit more bookish and began by arranging the re-release last year of Ginsberg’s 1994 four-album set, Holy Soul Jelly Roll onto iTunes.

She soon discovered that Ginsberg fans weren’t that interested in paying for an electronic download, when there were plenty of free or pirated recordings out there. Kossoff explained the same phenomenon applies to the contemporary music scene. When “paying for music” means listening to ad-enabled Spotify and Pandora, artists have to find profits elsewhere: concert sales, t-shirts, posters and books.

So what, then, could be done for Allen in the digital age?

Ironically, the answer was to return to the era of physical media, from whence Ginsberg came. She and Hale have re-released First Blues on vinyl –faithful to the original, right down to the newspaper insert and the typos on the packaging. Anyone who buys one of these limited-edition records also gets a free link to download the tracks digitally.

And it appears to have worked. They sold out of records before the Housing Works event even started — and more are on sale now. Satisfied with this model, Kossoff and Hale intend to continue their collaboration with new re-issues of Ginsberg’s music.

From his first reading of Howl in 1955 to his death in 1997, Allen Ginsberg produced poetry, music, and spoken word at a delirious pace and he recorded himself and his collaborators whenever possible. According to a 1994 article in the New York Times, Ginsberg was a “compulsive collector” and a “pack rat” whose personal archives include over 300,000 items, ranging from “mail from an admiring high school student named Abbie Hoffman [and] the sneakers Mr. Ginsberg was wearing when he was kicked out of Czechoslovakia in 1965” to “report cards from East Side High School in Paterson, N.J., electric bills and restaurant receipts […] with Mr. Ginsberg’s annotations.” Among the hundreds of tapes are “readings, telephone chats with William S. Burroughs, jam sessions with Bob Dylan,” but surely also countless hours of idle chatter.

These tapes have now made their way to Stanford University, where they are being reviewed and catalogued by academics, but Peter Hale sees potential in the idea of using social media to crowd-source the mining expedition — allowing the community-at-large to become collaborators too, finding history in the echoes.

But because Ginsberg read all around the world in all kinds of company, recordings are still materializing out of the ether, some sixteen years after Ginsberg’s death. In 2008, an academic working on a biography of Allen’s friend Gary Snyder accidentally stumbled across a recording at Reed College, which is now the earliest-known recording of Ginsberg’s “Howl”.

According to the Guardian, the early recording was made in the winter of 1956, only a few months after he first performed the piece. According to biographer Barry Miles, Ginsberg is more quiet and subdued in this early reading than in the dramatic performances he later gave. Indeed, after about 35 minutes, Allen stops abruptly, explaining, “I don’t really feel like reading any more. I just sorta haven’t got any kind of steam.”

Last July, a blogger posted a recording of Ginsberg performing with Peter Orlovsky, Steven Taylor and Harry Hoogstraten at a small bar in Eindhoven, Holland. The recording had been “discovered only recently after reportedly gathering dust on Hoogstraten’s shelf for thirty years.” Another recording, featuring a 1977 Ginsberg collaboration with avant-garde composer Arthur Russell was found in 2003 by a record producer who was digging around in a Long Island City storage-facility.

Hale hasn’t been surprised by discoveries like these. He showed me a Ginsberg recording that someone had mailed him from Arhus, Denmark in a strange format he hasn’t yet figured out how to play. Hale works out of the building that Allen Ginsberg bought on East 13th street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Guests and collaborators often stayed at the building while Allen was alive, and part of it is still rented out as artistic space. This seems appropriate to the abiding spirit of generosity that echoes through every memory of Ginsberg by his many collaborators. Hale told me, “Allen was the sort of person who would stop on the street and start talking to the homeless guy who’s talking to himself. He’d say to him, ‘Now what are you crying about?’”

Perhaps nothing captures this spirit quite as beautifully as this article from The New Yorker’s “Department of Immortality,” which describes how Ginsberg famously loved inviting his compatriots over for soup and even installed a special shelf just to hold his twelve-gallon stockpot. His secretary since 1977, Bob Rosenthal, saved two jars of the last batch of fish chowder that Ginsberg ever cooked for his company. For sixteen years, Rosenthal has been looking for a museum that could properly display them. In the meantime, he has kept the jars in the freezer at the 13th street building, where they still sit on ice, as of the time of this post.

There is so much of Allen’s genius still alive, in boxes and on tape and in jars, that it doesn’t seem like he’s gone. When I woke up, the day after chatting with Hale, to find that Allen Ginsberg had “liked” me on Facebook, it only felt a little strange. The Allen Ginsberg fan page on Facebook, created in 2011, 14 years after Ginsberg’s death is maintained by his estate and has been “liked” by nearly 57,000 fans. I don’t think Ginsberg was one for computers, but he was certainly into social-networking long before it was cool.

Because of course, he also lives on in the hundreds of people he worked with, who remember him fondly. At the Housing Works event, Bob Rosenthal recalled that “Allen didn’t have a naturally beautiful voice” but that he decided to sing anyway, because he firmly believed poetry and music were linked. “Don’t forget that Homer sang!” Rosenthal added, “Maybe.”

According to Rosenthal, Ginsberg also believed in improvisation. “He said if you can read off a piece of paper then you can read off your mind.” He described how Allen’s eyes would sometimes roll into his head as if doing just this as he began to go off-book while reading a poem. Then he read a poem called “Starry Rhymes”, one of the many that Ginsberg wrote in March of 1997, while he lay in a Beth Israel hospital bed, just before being diagnosed with general organ failure.

David Amram recalled how Allen’s singing career began when they finally convinced Bob Dylan to come to one of their parties — after trying for twenty years. Singing allowed Ginsberg to embrace the performance side of poetry and, according to Amram, avoid becoming an academic poet in the “University death scene.” Amram’s song involved accompaniment by a banjo and a glockenspiel, as well as him playing two strange Chinese flutes (simultaneously) and instructing the audience to sing in Mandarin, “I am happy to be on Crosby Street.”

Amram’s advice to the young people of the crowd was to “Hang out with people who say ‘Yes… let me see what you’re doing.’ Egotistic, greedy, selfish narcissism is an overcrowded field in a non-growth industry.”

Later, Hettie Jones recalled teaching Allen to sing in Hebrew for a recording of Kaddish, at a time when she had recently been cast out of her own Jewish family. She mused happily that in accordance with Ginsberg’s wishes, a third of his ashes had been scattered in the West, a third in the East, and a third in the middle. “Now he’s finally given himself to everyone. What was not possible in life is possible in death.”

Writing anything — poetry, novels, cookbooks, blogs — can be a lonesome business. It takes hours of solitude, contemplation, scribbling, revision; it can make bad friends of us. Trying to make something good enough to last, we tend to lock our generosity away, like so many frozen jars of soup. Literary history is rife enough with isolates, loners, and introverts, but Allen Ginsberg stands for the other, shining possibility. That words can be connective tissue; that the guy shouting on the street corner might just be onto something; that, in fact, you ought to grab your kazoo and go accompany him; that you should grab your tape recorder too, because it might just be genius.

At the end of the night, after thanking everyone for coming, the host remembered that Ginsberg was always fond of reminding both friends and interviewers that “immortality comes later.”

“Now,” he said, “It’s later.”

***

— Kristopher Jansma is a writer and teacher living in New York City. His debut novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, will be published by Viking Press in March 2013. Want more Literary Artifacts? Here you go.