Books & Culture

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: the quixotic search for Cervantes’s bones

Cervantes: Lost in La Mancha, Found in Madrid. (Maybe. Probably. We Think.)

Each month in the Literary Artifacts space, writer Kristopher Jansma writes about his encounters with rare books, writerly memorabilia, and other treasures in New York City and around the world, hoping to discover how the internet age is changing the face of literature as we know it.

Somewhere deep inside the Convento de las Trinitarias Descalzas in Madrid, historian Fernando Prado is searching amidst the holy books and cloistered nuns for the man who wrote the first modern novel, published 407 years ago today: Miguel de Cervantes — or whatever’s left of him.

The plaque on the exterior of the convent memorializes the author of the great Don Quixote, who is buried inside. Probably. They’re pretty sure he’s in there somewhere. Just no one’s quite sure where. Cervantes’s bones may have been moved to another convent nearby during a 17th century renovation. Although it’s thought they were moved back again, and that they weren’t disturbed at all when, in the 20th century, part of the convent was converted into a courthouse. However, what’s certain is that he was buried there initially — at least it said in his will that he wanted to be. Though Cervantes himself was not a member of the “Barefoot Trinitarian” sect that runs the convent to this day, they once helped ransom him out of slavery, and one of his daughters belonged to the convent (they think). All we really know for sure is that the great author died nearby, in his home, of dropsy (only it may have been cirrhosis of the liver, or possibly diabetes) on April 23rd, 1616, just ten days before William Shakespeare. Except that Spain was using the Gregorian calendar and England the Julian… so really they died on the same day.

OK, fine. Really all we actually know is that he’s dead.

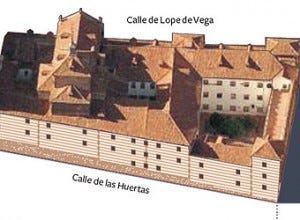

None of this uncertainty has dissuaded Prado, however, who has obtained unprecedented permission from the nuns, the archbishop, and the Spanish Royal Academy to use geo-radar technology to scour every inch of the 3,000 square foot convent to find the long-lost bones. (Prado believes they were never moved in any of the reconstructions). It’s possible, by the way, that they aren’t in the floors, per se, but maybe in the walls, so they’ll be checking those too. Also, in the towers and outside in the tangerine garden. Just to be safe.

As if this all weren’t quixotic enough, there are likely to be hundreds of other people buried in the convent, and there’s a strong possibility that Cervantes’s bones may have gotten mixed in with the others’ somewhere along the way. Prado does admit that the four-century-old bones probably will not have enough DNA to permit a comparison with the known, modern descendants of Cervantes’s brother, which is why he’ll have to use more creative methods to identify the correct skeletal remains. In 1571 Cervantes fought in the mighty Spanish navy against the Ottomans, and that during the course of the Battle of Levanto he got shot twice in the chest and once in the arm by something called a “harquebus” (I’m not making this up) while floating around off the coast of Greece on an oar-powered galley ship. The gunshots are believed to have shattered his ribs and forearm, and it is by these distinctive markings that Prado hopes to identify Cervantes’s remains today. “If a person does not use one arm for more than four decades, as happened to Cervantes, that would influence the shape of his entire skeleton,” Prado explained to German news agency, Deutsche Presse-Agentur.

If he does locate the bones, Prado hopes there will be further forensic evidence to settle other long-standing questions, like whether or not Cervantes really did drink himself to death, and what kind of food he ate as a child. Bioanthropologist Kristina Killgrove, explains on her blog that long-term alcoholism is known to cause bone degeneration, which could be visible still, although she points out that such decay could just as easily have been caused by a Vitamin D deficiency, or, you know, being dead for 400 years.

But this is just the beginning. Tilting at a somewhat-larger windmill yet, Prado is also hoping to create a model of Cervantes’s skull and, from there, extrapolate and reconstruct his facial features, so that we can once and for all know what he looked like. His only known portrait was painted 20 years after his death, and so not nearly as reliable as a computer image based off a 400-year old skull, which may or may not really belong to Cervantes — if they can find him, if he’s even buried there. Killgrove points out that this is a trendy technique these days among forensic archaeologists, who’ve attempted to make Mona Lisa and William Shakespeare smile back at us from beyond the grave… but that in reality the concept of seeing anyone’s “true face” using these methods is “absurd”.

Prado who hopes to have this all wrapped-up by 2016, in time for a global celebration of the 400th anniversary of the death of Cervantes and Shakespeare, says he’d like to address “an injustice and neglect of Cervantes” and, as absurd as the entire thing might be, I can’t help but hope that he pulls it off.

Maybe Prado has seen one-too-many Indiana Jones movies, read a bit too much Dan Brown, but let us not forget that Don Quixote himself would not have embarked on his own journey had he not read one-too-many chivalric tales. To the Spaniards he encounters during his quest, Don Quixote seems pathetic, idiotic, senile, and even completely insane, but to himself and to us readers, The Don is simply daring “to dream the impossible dream”. Quixote reminds us, in his way, to embrace life’s grand ironies and futilities. His epic war with reality certainly seems to have fueled four centuries of novelists that followed, from Tristram Shandy to Madame Bovary and Dostoevsky to Borges. The great director Orson Welles famously spent almost thirty years trying to make a film of Don Quixote, and failed spectacularly. But this did not dissuade Terry Gilliam in the slightest from embarking on his own Quixote film, a decade later. And when NATO, flash floods, and chiropractic injury beset the adventure, Gilliam helped turn the failure into a documentary of failure called Lost in La Mancha. And today? Gilliam is still trying to finish the original film.

When this world’s puzzles beget more puzzles, Cervantes reminds us that it has always been this way. Prado’s quest is probably foolhardy, but at least it is epically foolhardy. He’s not dissuaded by the odds, and why should he be? Neither are the thousands of tourists who flock each year to visit the great plaque on Calle de Lopa de Vega, at the heart of Madrid’s barrio de las lettres, even though the convent is closed to the public (though the nuns do conduct a special mass every year on April 23rd, in honor of Cervantes). The other 364 days a year, all tourists can do is pose for photos outside beneath a large engraving of the famous knight-errant, boldly hoisting his lance and sitting astride a slumping steed, the ever-faithful Sancho Panza scurrying along just behind. In a way, all of us readers are Panzas, scrambling to get as close as we can to our heroes.

What makes us want to follow these writers to their graves? Each year, literary tourists flock to Montparnasse to see Beckett and Sartre, or Amherst to see Emily Dickinson, Fluntern to visit James Joyce — for my own part, I’ve left a few flowers on Willa Cather’s grave in New Hampshire, where she is buried alongside her long-time special-lady-friend Edith Lewis, and once, in Rome, I was very nearly arrested (OK, I just got yelled at a lot) for trying to break into the Protestant Cemetery to see the grave of John Keats. But if you think that’s a bit extreme, then, well, let me introduce you to this Canadian blogger, who would like to buy the bones of Cervantes off Prado once he’s done with them, so he can display them in his home like Michael Jackson did with the Elephant Man. (I think he’s kidding.)

Though the Electric Literature blog budget was sadly not sufficient to send me to Madrid, I sought out a statue of Cervantes right here in New York City, which was given to us by Spain in 1986. For a time it stood outside the New York Public Library in Bryant Park, until it was moved to a small hard-to-find courtyard just north of Washington Square Park. But standing in front of a bronze likeness of the man was still quite moving, even if it probably looks more like Jeffrey Eugenides than the real Cervantes.

Perhaps because their words live on and on, seeing the monuments and graves of writers is a sometimes-needed reminder that they were only ever as human as any of us. The epics that shape our lives today were once shaped by theirs. Is it any wonder that Prado wants to reach back through time and touch the shattered limb of his country’s greatest literary figure?

***

— Kristopher Jansma is a writer and teacher living in Manhattan. His debut novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards will be published by Viking Press in 2013. He has studied The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University and has an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University. He is a full-time Lecturer at Manhattanville College and also teaches at SUNY Purchase. Recently, his short story “A Summer Wedding” won 2nd prize in The Blue Mesa Review’s 2011 Fiction Contest, judged by writer Lori Ostlund. His essays and fiction can also be found on The Millions, ASweetLife.org, The 322 Review, Opium Magazine, The Columbia Spectator, and The (Somewhat) Complete Works of Kristopher Jansma. You can also find him on Facebook.