Books & Culture

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: You Say You Want a Revolution? Zines at the Brooklyn College Library

Pop quiz. Which great thinker and important cultural revolutionary wrote the following?

“We are caught within the gears of a system that is primed to generate loss, trauma, and grief while leaving us scrambling and struggling for the resources and social supports we need to process this grief. To claim our grief — to claim that our relationships with each other matter — within this climate of isolation and denial is itself a radical act.”

Was it Gertrude Stein or Marcel Duchamp? Thomas Paine or Benjamin Franklin?

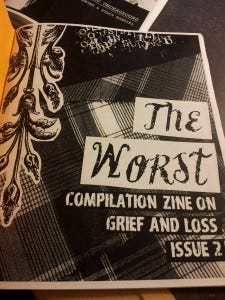

No, those would be the bold words of Kathleen McIntyre, in the second issue of The Worst: A Compilation Zine on Grief and Loss, which I found not in the back of St. Mark’s Bookshop or some anarchist café, but in the new Brooklyn College Library Zine Collection.

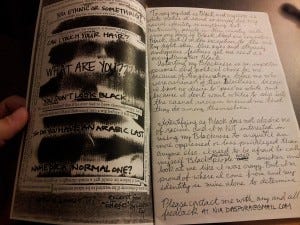

Armed with nothing more than scissors and glue, the zinesters represented in the collection seek nothing less than the deconstruction and redefinition of every element of our society — gender, race, sexuality, capitalism, history, the Internet — and they’re prepared to undermine your dearest assumptions, one photocopied page at a time.

If you have never seen a zine before, they are difficult to describe, because each is, by definition, something that

defies definition. Alycia Sellie, who curates the Brooklyn College collection, explains that zines “are limitless, ephemeral and ever-changing.” Fundamentally, they’re a DIY-art form, booklets assembled out of written words and appropriated images. Often they are collaged together in a way that leaves the rough edges showing. It’s like a cut-and-paste magazine, where you can still see all the cuts, and all the paste. This raw aesthetic often mirrors the content: censor-free, frequently-explicit, and many times mind-bending. Every zine is unique; even within the same series, Issue #1 will sometimes look nothing like Issue #2. It isn’t about branding or commercial success. They’re cheap to make and cheap to buy, some even instructing readers to discreetly send a few dollars through the mail for the next issue.

At ‘Fold, Staple, Share’, a reading celebrating the opening of the collection this summer, one reader explained that “Zines allow those outside of power to be heard. You don’t need money or privilege or even an education to make a zine.” It is street art; it is punk rock. It is, as another reader at the collection’s inaugural bash put it, “a space to yell.”

Though the history may go back to the turn of the century (more on that in a moment), the zine-as-we-know-it emerged out of the social upheaval and culture wars of the 1990s. Young artists and writers stuck in boring corporate office jobs, feeling hopelessly far from the mainstream, took matters into their own hands and began to construct their own megaphones (many times using the very Xerox machines to which they were enslaved).

I appropriated my own DIY-definition of zine from a 1995 episode of This American Life called ‘Quitting’. In the prologue to the episode, writer Evan Harris tells host Ira Glass how she came up with the idea for her zine, ‘Quitter Quarterly’ while stuffing envelopes with a co-worker in the mailroom of her soul-sucking job: “Shouldn’t the letter Q be further towards the back of the alphabet?” she asked her friend.

This banal question launched a conversation that changed Harris’s life. Soon they decided that “Q, in their mind, has more character. Q… doesn’t take anything off of anybody. It makes demands and it sees that they are met. What other letter has an adjunct, a bodyguard with it, carried into every word? In their mind, Q belongs at the end of the alphabet, with your Xs, your Ys, your Zs. Letters that do not care what anybody thinks of them and that don’t just join up to any word. And Q, of course, is the first letter of the word ‘quit.’”

A zine is like the letter Q: Something strangely simple, but that makes big demands. Something of character, that’s not going to take any lip. Something that questions everything, even its own order in the alphabet. Something eager to quit the dominant paradigm.

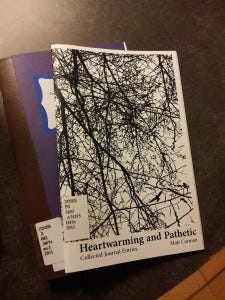

I didn’t spot any back-issues of ‘Quitter Quarterly’ in the collection, but you can find such titles as “Angry Black-White Girl: reflections of my mixed race identity”, “Borderlands: It’s a family affair”, “Heartwarming and Pathetic”, “Shotgun Seamstress”, “Brooklyn!”, “Life of Vice”, “I Love Bad Movies”, “Hoax: feminism and hirstories”, “The International Girl Gang Underground Zine”, “People of Color Zine Project”, and “Rage On/Radical Domesticity”, which informs readers “how to live collectively in a socially responsible way.”

At the ‘Fold, Staple, Share’ reading, the creators of some of these zines read excerpts, alongside Brooklyn College teachers and students. One writer reminisced about her first zine, made at the age of 15 with a friend over the course of a weekend left alone with her mother’s Xerox machine. She stressed the importance of seeing “real handwriting” all over the finished product, saying that it was a lot more fun to cut things out of magazines than to write in HTML. She compared the experience of assembling a zine to the primal thrill of hunting and gathering, and confessed to “the idealistic notion that [she] could feed everyone with what’s inside.”

Sophia, a sophomore, wrote about growing up in the housing projects of Park Slope. Another student wrote about his Native American identity. “There is a common misconception about Indians. Namely everything,” he wrote. This was followed by a poem — actually, an etude, as he called it — entitled “People Don’t Usually Vomit on Me (After We Make Out).”

A zine has the “energy and passion” of an oral history, explained student Elvis Bakaitis as he read from his zine “Homos in Herstory,” which is laid out like a graphic novel and illustrates the “19th century Golden Age of Romantic Friendships,” personified by the not-uncommon Boston Marriage. He spoke ambitiously about his hopes to expose the hidden Queer History of America; he hopes to become a librarian after he graduates.

In fact, several of the zine-writers said they were librarians-by-day, and Professor Sellie herself is both a librarian and the maker of the zine The Borough is My Library. She explained, “It may seem antithetical for librarians — who are stereotypically interested in order and organization — to be involved in the chaos of zine-making, but many librarians create zines.” Sellie cited Sean Stewart, of the Zine Librarian Zine, who inquires, “Are librarians drawn to zines because they recognize in these bizarre, photocopied publications the passion for freedom of expression that they themselves so proudly stand for?”

Of course, librarians also have easy access to photocopy machines, so I asked Sellie if she agreed with my

understanding that the zines of the 90s were in some way brought on by the advent of the low-wage corporate job and the Xerox machine. Like a true librarian, Sellie referred me to a book called The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, in which Elizabeth Eisenstein credits the Gutenberg printing press with the social upheaval that ultimately ended the Dark Ages in Europe, setting the stage for the Reformation and the Scientific Revolution. But Sellie cautioned against this perhaps too-deterministic view of technology, and offered a counter-argument from How to Acknowledge a Revolution by Adrian Johns, who reminds us that credit shouldn’t belong to the machine, but to the humanity which invented and utilized the machine.

But the technology question bugged me for another reason. Why, in the age of Facebook and Twitter, when practically everyone is a blogger whether they mean to be or not, are people still making zines by hand? I can understand being nostalgic for the 90s, but we have to admit that today the Internet is everything those early zine-sters wished for: cheap, free of censorship, accessible, and socially inter-connecting. Unheard voices no longer have to shout to one another through toilet-paper tubes tied together with string, and yet zines appear to be alive and well.

Sellie offered one possible explanation. “The advantage of making a printed zine today is that you aren’t constricted to what you can accomplish electronically. When I make a zine, I typically use a typewriter, markers, glue, pencils, the photocopier, stamps, silkscreens and found images/collage. I make my zines as a way to get away from screens for a while, and to enjoy making something by hand.”

Zines are not simply retro-nostalgia, but a welcome break from the digital devices that so often dominate our day-to-day lives. It’s the same reason my neighbors in Brooklyn are mixing their own bitters and hewing their own skateboards. In this world of a zillion websites, it is comforting to know we can still make things by hand.

But Sellie also pointed out that the web and zines go hand-in-hand today. Most of the zines in the collection have some presence on the web. Some have their own Tumblr; others are sold on Etsy. There are even social networking sites like We Make Zines, specifically built to connect people to zines, and zines to people.

After a few hours leafing through the zines at Brooklyn College, I hopped a 2-train back up to the Brooklyn Museum, where the museum library has, in its own collection, a zine from long, long ago. It is kept in a climate-controlled room and its fragile pages must be handled under a librarian’s supervision.

It was June of 1914 when London editor Wyndham Lewis began working with little-known writers like Ezra Pound and Ford Maddox Ford to create BLAST, which damned the middle class of England for perpetuating Victorian tastes and conventions, declaring itself to be “a battering ram” against the mainstream. With its hot pink cover, cubist illustrations by Gaudier-Brzeska, and sporadic use of GIANT CAPITAL LETTERS, the magazine certainly was eye-catching, as were its imagist poems and manifestos of a dedication to “the point of maximum energy,” which they called Vorticism.

“LONG LIVE THE VORTEX!” it begins. “Long live the great art vortex sprung up in the centre of this town! We stand for the Reality of the Present — not for the sentimental Future, or the sacripant Past. We want to leave Nature and Men alone. We do not want to make people wear Futurist Patches, or fuss men to take pink and sky-blue trousers. We are not their wives or tailors…. We will convert the King if possible. A VORTICIST KING! WHY NOT? DO YOU THINK LLOYD GEORGE HAS THE VORTEX IN HIM?”

The next twenty pages list people, ideas, and things to “blast”, such as England, apertifs, the Suez Canal, the art-pimp, fraternizing with monkeys, and the years from 1837 to 1900. But it also lists things to “bless”, such as England, seafarers, hairdressers, masterly pornography, and Shakespeare.

Though BLAST was initially conceived as a quarterly publication, World War I erupted and it took more than a year to print the second issue, which was also the last. It included poetry by newcomer T.S. Eliot and an essay written by Gaudier-Brzeska in the trenches of France: “I HAVE BEEN FIGHTING FOR TWO MONTHS and I can now gauge the intensity of Life. HUMAN MASSES teem and move, are destroyed and crop up again. HORSES are worn out in three weeks, die by the roadside. DOGS wander, are destroyed, and others come along. WITH ALL THE DESTRUCTION that works around us NOTHING IS CHANGED, EVEN SUPERFICIALLY. LIFE IS THE SAME STRENGTH.”

At the bottom of the page was a note from Lewis, explaining that, shortly after sending the essay to BLAST, Gaudier-Brzeska was killed in the trenches of France. This 99-year-old piece of paper was both his obituary and his self-written eulogy. It called to my mind those two sentences that I’d read an hour earlier, in Kathleen McIntyre’s Zine on Grief and Loss.

Perhaps, thanks to Sellie’s efforts, in another 99 years, someone like me will go into the Brooklyn College Library and put in a request for that same, aging copy of The Worst. That future-me would wait patiently for it to be taken out from an moisture-conditioned room and then, while a librarian looks on, he might carefully turn the pages and read the revolutionary sentiments of another age entirely, but one not so different from his own.

***

More Literary Artifacts here.

***

–Kristopher Jansma is a writer and teacher living in Manhattan. His debut novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, will be published by Viking Press in 2013. He has studied The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University and has an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University. He is a full-time Lecturer at Manhattanville College and also teaches at SUNY Purchase. Recently, his short story “A Summer Wedding” won second prize in The Blue Mesa Review’s 2011 Fiction Contest, judged by writer Lori Ostlund. His essays and fiction can also be found on The Millions, ASweetLife.org, The 322 Review, Opium Magazine, The Columbia Spectator, and The (Somewhat) Complete Works of Kristopher Jansma. You can also find him on Facebook.