Books & Culture

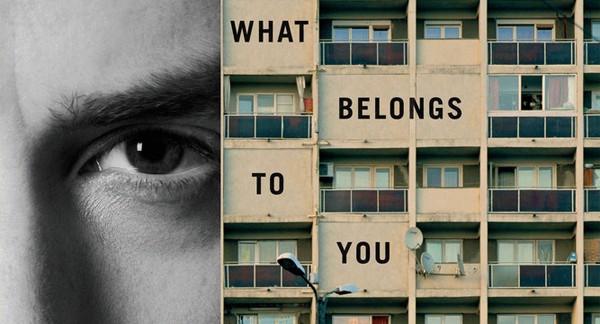

Lost in Translation: What Belongs to You by Garth Greenwell

Reading Garth Greenwell’s debut novel, What Belongs to You, abroad — for me, that currently means outside of the United States — is a particularly vivid, and strangely enriching, experience. Partly, this is because the plot is set entirely in Bulgaria, where the narrator is a teacher at the prestigious American College in Sofia. Additionally, since the book deals so much with the foreignness of attitudes and emotions as well as language, reading it in transit and in guest bedrooms feels incredibly apt.

What Belongs to You is a beautiful first book, with a focus on communication, on understanding (or not), often literally, what other people are saying. So convincing is its narrator that it feels autobiographical, though I have avoided asking Greenwell whether he lived and taught in Bulgaria, as it could break the thrilling illusion that reading the book is a voyeuristic invasion of a very real narrator’s private thoughts, actions, memories, and emotions. Like many of the great novels written in the first-person, this one feels directed at someone, but that mysterious person isn’t necessarily us readers. This too contributes to the sense of sifting through an experience already translated through the narrator’s mind, where most of the interactions he has are in another language which he himself is not fluent in.

This narrator is left nameless throughout, because his name is “more or less unpronounceable” in Bulgarian, which is the language he uses when he meets the central figure, Mitko. Though the book is split into three parts, the middle one having ostensibly nothing to do with Mitko, the entire novel is permeated with his being, so clear in the narrator’s mind that it almost emerges from the book like a scent. The nameless narrator is saturated in Mitko’s essence from the moment he first meets the young prostitute. Although Mitko is never explicitly named as such, there is no doubt as to his profession. The first few pages of the book describe how the narrator finds him at a hookup spot for gay men in the restrooms at the National Palace of Culture in Sofia, where Mitko at first ridicules another man there who is there looking for sex. Wanting to be included, especially as he sees Mitko bearing “hypermasculine style and an air of criminality,” the narrator uses a head-waggling gesture that “signifies [in Bulgaria] both agreement and affirmation or a certain wonder at the vagaries of the world.”

From the very beginning, then, the reader and narrator alike are slightly lost in these vagaries of this world — the gesture doesn’t convey what the narrator wants it to — and so begins a spiral of abandoning precise understanding and embracing every moment with which Mitko graces us with his presence.

For Mitko is impossible to put together, to truly understand, and it is him, more than the narrator, who seems to be the focus of What Belongs to You. The narrator understands himself well enough, even when he’s perplexed by his own actions. He knows he cares for Mitko. He knows, during the middle section of the book, that memories of coming out to his father, his father’s disownment of him, will affect his decision to visit this distant personage on his deathbed. He knows, even when he is in a committed relationship, that it doesn’t and will never provide the satisfaction that Mitko does. Mitko is the drama of the narrator’s life, the moving piece that makes his routine exciting, the mystery that he can’t solve and therefore can’t let go. For much of the novel, he is out of the narrator’s and reader’s eyesight, but is in our minds as firmly as a tune stuck in our heads and refusing to leave.

At the very start, in the bathrooms where he’s introduced, Mitko seems menacing, a man both attractive and dangerous; maybe attractive because he is dangerous. But despite first impressions, Mitko often seems childlike to the narrator, especially during their first encounter, when Mitko takes his shirt off and reveals what seems like a much younger man’s chest: “He was thinner than I expected, less defined, and the hair that covered his torso had been shaved to bare stubble, so that for the first time I realized how young he was (I would learn he was twenty-three) as he stood boyish and exposed before me.” This apparent vulnerability in Mitko is confusing to the narrator, at odds with the prostitute’s earlier hypermasculine attitude.

This confusion extends to the narrator’s own life, his very existence in Bulgaria, his teaching career, his relationships with his family, and the dichotomy between his personal and professional lives. Though he doesn’t hide the fact that he’s gay — a fact revealed later in their acquaintanceship — Mitko believes that the narrator is keeping his sexuality a secret, masquerading as a straight man. In fact, it is Mitko who masquerades as straight by defending the narrator from people who call him a fag, even while Mitko’s profession, his livelihood, depends on men giving him money, food, and shelter. But Mitko calls these people priyatel, “friends,” rather than clients, and sees their payment as “help” freely given, as generous “gifts.” Perhaps this is truly how he thinks of them, but for all intents and purposes, Mitko — as the narrator knows well — is a man with a body and charm for hire, for barter, for sale. On a night Mitko spends at the narrator’s apartment, the latter sees this firsthand: Mitko spends hours on the narrator’s computer, talking with countless men of varying ages on Skype. He even introduces the narrator at times, shifting the computer’s camera, and the oddness of this situation is impossible to escape, as Mitko seems to really be introducing one friend to another rather than breaking any confidences or outing anyone, which is essentially what he’s doing.

When Mitko and the narrator have a falling out, the latter believes he is seeing Mitko’s real face for the first time — a violent face, one that is powerful and which belongs to a frightening underworld of crime. After all, he’s seen Mitko full of bruises and cuts before, known that Mitko is involved in various nefarious activities, and suspects he enjoys brawling. The fear that the narrator feels, however, is one of the only moments in the book where his emotion seems outsized, exaggerated; one of us, reader or narrator, is mistranslating Mitko’s threats. To me, they seemed empty, full of Mitko’s bluster, his need to assert control in a life of extreme poverty — he is basically homeless, staying with clients as often as possible during the night — where his only safety net is people like the narrator who treat him well. For all I know, Mitko’s bruises come not from brawling but from client encounters. To the narrator, however, the threats are all too real.

This is the end of the first bout of the narrator’s constant suffering over Mitko. In the novel’s second part, we learn more about the narrator’s childhood, family, and — again — the misunderstandings that came along with his discovery that he was attracted to other boys when he was just a boy himself. There is still a distance from the reader in the writing here, a feeling of the narrator’s exposure of memories being put through the sieve of a grown-up’s perspective on his past. There is something that is reminiscent of Karl Ove Knausgård’s translated My Struggle series in this middle section especially, which is fascinating considering that Knausgård’s books are translated into English whereas Greenwell’s novel isn’t. But Greenwell is able to employ a guardedness to his narrator that feels like the distance of translation. This is showcased when the narrator shows his mother around Bulgaria when she comes to visit: there is a gap between the two of them, due to the past, but also due to his constant need to literally translate everything around them for her. She, like Mitko, is dependent upon the narrator, dependent on his kindness, patience, and generosity.

In the final part of Greenwell’s book, Mitko returns, and while he manages to reassert control over the narrator with a brief bout of groping in a public bathroom, the connection between the two is not what it used to be, and the power dynamic has shifted. Mitko is ill, both with syphilis and with a longstanding liver disease, and for once the narrator cannot actually understand what he’s saying, or why he’s saying it: “men me nyama, men me nyama, I’m gone, it means, or I’m not here, literally there’s no me, an odd construction I can’t quite make work in English.” Again the narrator returns to the unpronouncability of his own name, as Mitko calls him “that syllable […] used to approximate it.” A syllable the reader is never privy to, and part of the privacy that the narrator manages to seal inside the translation of his thoughts and feelings to the page.

**

Mitko and the narrator’s first contact — and contract, for Mitko received money for it — ends in the narrator’s anger, for he wasn’t given what he wanted in their encounter. Nevertheless:

“[M]y pleasure wasn’t lessened by [Mitko’s] absence, […] what was surely a betrayal […] had only refined our encounter, allowing him to become more vividly present to me even as I was left alone on my stained knees, and allowing me, with all the freedom of fantasy, to make of him what I would.”

It is this, Mitko’s unavailability, his inability to be completely understood by the narrator who is never fluent in Bulgarian, that makes him most attractive, since he is then the subject of fantasy. But by the time he is faced with Mitko’s realities, the narrator has found companionship, maybe love, with a man called R.

And so finally Mitko is an open book for the narrator to read, and once he’s read it, discard:

“Love isn’t just a matter of looking at someone, I think now, but also of looking with them, of facing what they face, and sometimes I wonder whether there’s anyone I could stand with and watch what I wouldn’t watch with Mitko, whether with my mother, say, or with R.; it’s a terrible thing to doubt about oneself but I do doubt it.”

This is one of the most honest and open things the narrator states, as is his telling Mitko: “I am an open person, I don’t have these secrets, everyone knows what I am,” meaning gay. But the narrator might as well be speaking about himself in general, and in that sense he is clearly opaque to himself as well, for he is not an open person, he does have secrets, and “everyone” doesn’t include the ones reading his words on the page. Beautiful, vulnerable, the narrator is more thought than action in type, more philosophy than feeling, more objectively descriptive than intimately there, and so while it is impossible not to love him, as it is impossible for him not to love Mitko, the narrator is a mystery, lost in translation to the reader, but better, and more interesting, for it. If we could read him as he reads Mitko in the end, maybe we’d discard him too; Greenwell makes sure this doesn’t happen.