essays

NEW GENRES: Country Noir

[Editor’s note: New Genres is a recurring feature that aims to complicate and expand our conception of literary genres and their always porous boundaries.]

Country noir carves out a space for the small, the local, the defiant and the defeated. That losing side of the American mythology that walks out of the shining city on a hill spitting and reaching for a flask. Take this line from Benjamin Whitmer’s Pike:

“ … Jack used to have plans for his life.”

“Most of us did,” Pike says. “Before we became what we are.”

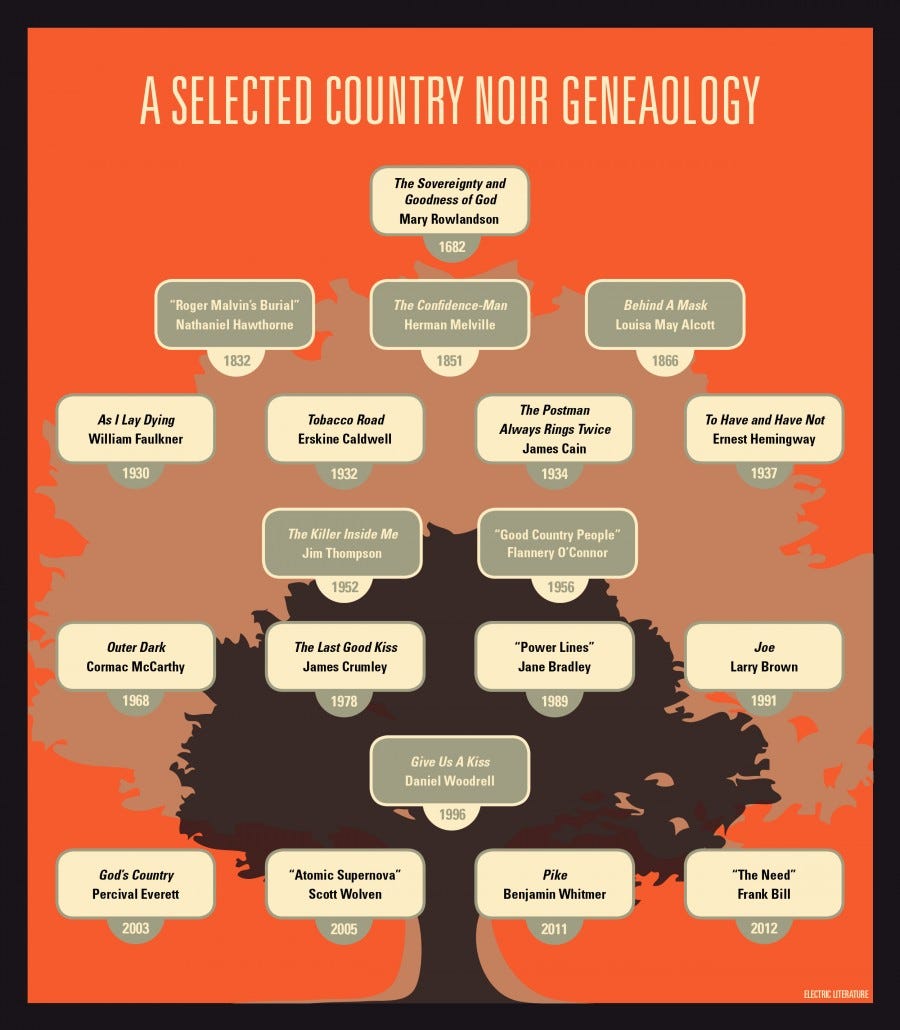

Daniel Woodrell coined the term “country noir” with his 1996 novel Give Us A Kiss: A Country Noir. He has since had the subtitle removed in subsequent editions and distanced himself: “The term ‘country noir’ isn’t even worth using any more. … I don’t want to be required to live up to my own definition.” Fair enough, but to coin a term does not mean you’ve defined a term. His novel constitutes neither the beginning nor end points of country noir.

In fact, country noir has a long-hidden tradition in American literature with roots that reach back to 1682, beginning with the unlikely-sounding The Sovereignty and Goodness of God, by Mary Rowlandson. The book’s opening plunges us straight into the slaughter of Rowlandson’s family by marauding Indians and her forced captivity into the wilderness. Her description of the experience after being “redeemed” serves as an accurate summation of the country noir outlook as can be imagined:

I can remember the time, when I used to sleep quietly without workings in my thoughts, whole nights together, but now it is other ways with me … I have seen the extreme vanity of this World. One hour I have been in health, and wealth, wanting nothing: But the next hour in sickness and wounds, and death, having nothing but sorrow and affliction.

The tropes of Rowlandson’s journey become familiar ones in country noir: the violent fall from grace with uncertain prospects of ever returning to bliss, hyper-local concerns that stoutly do not form a symbolic template for any larger spiritual or political happenings. The characters of country noir don’t look to the wider world — they are inextricably mired in their own personalities, locales, family arrangements, and social classes.

Over and against the overweening hubris of the American Dream, country noir looks to the broken-down farmhouse, abandoned in a pasture, with its dreams long gone and broken. It flips the bird to social conscience, ideology and utopian hopes, turns to the bar for another red beer, contemplating the tottering of social order against the meth epidemic, the plight of returned veterans abandoned by their country, the fate of fugitives. There is no epic sweep to these stories, no recourse to a mythology which sweeps us all along to a manifest destiny.

Country noir occurs beyond the aegis of the city and the suburbs. Its rural settings bring the actions and characters into sharp relief, stripping away social context and revealing its humans as naked, trembling, and very horribly fallible. Eschewing social commentary and symbolism, country noir prefers to dwell in the more homely environs of story.

No crusaders appear. Characters may be victims, passive or flailing, of vicious social circumstance, but while there may be a good deal of awareness of the haves, they will remain have-nots. The swindling Bible salesmen in Flannery O’Connor’s “Good Country People,” for instance, certainly has some idea what he’s missing out in the pleasant homes he visits. Many lives in country noir works are worn out over amounts of money that would be beneath the notice of the prosperous; from Rueben Bourne accidentally murdering his son in the wilderness after going broke in Nathanial Hawthorne’s “Roger Malvin’s Burial” to the unnamed fugitive in Scott Wolven’s “Atomic Supernova” eking out a living in the Nevada badlands recycling metal and running drugs, the characters of country noir works are generally not economic winners.

infographic by Nadxi Nieto

This is a highly disparate genealogy, to be sure. Acknowledged American classics stand alongside “mere genre” writing. However, I hold that artificial genre boundaries ought not constrain our view of literature. What binds these works together across time is not a conscious adherence to a certain literary style or genre; rather, these works are exemplars of the dark shadow cast by the burgeoning American dream across the North American continent.

Country noir peels back the edges of those illusions. Larry Brown’s Joe (soon to be a motion picture) paints a Cormac McCarthyesque picture of the rural South, unflinching in its portrayal of quotidian economic realities. Unable to look beyond his routine of whiskey and work, Joe’s shredded moral compass barely guides him through his rough days, while the father who pimps out his own pubescent daughter is not the worst character to put in an appearance.

For if country noir is about nothing else, it is about characters who lack for good choices, or often, many choices at all. The scammers aboard Melville’s Mississippi tramp in The Confidence-Man are conned to the extent of their own naiveté and willful blindness, while the Bundren family in Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying has been poor and getting poorer from the beginning. Even the apparent wealth of Abraham Trahearne in James Crumley’s The Last Good Kiss is revealed to be a sham; he is deeply in debt and living off the largesse of his mother and ex-wife, both of whom despise his current wife, the woman of mystery at the heart of the novel’s story. Chronic economic insecurity haunts the characters’ actions, especially the ones that are despicable, desperate and unwise. Consider Harry Morgan in Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not:

I could stay here now and I’d be out of it. But what the hell would they eat on? Where’s the money coming from to keep Marie and the girls? I’ve got no boat, no cash, I got no education. What can a one-armed man work at? All I’ve got is my cojones to peddle.

That’s country noir. Or as Hank Williams put it a long time ago: “I’ll never get out of this world alive.”

Country noir makes short shrift of the notion of a hero riding to the rescue, howsoever rough he is around the edges. Country noir is all rough edges. Wayne in Frank Bill’s short story “The Need” can chase solace in drugs before finally succumbing to ultimate violence, while the young boy in “Power Lines” by Jane Bradley will not have his voice heard, and an innocent ghost of a black man, himself a victim of great injustice, takes the blame instead. In Percival Everett’s God’s Country, the fiendishly stupid Curt Marder succeeds only in losing what little grubstake he has, while George Armstrong Custer is portrayed as a bumbling, effeminate idiot who blunders into the massacre at the Little Bighorn and the black tracker Bubba rides a mule because “Nobody ever wonders if a mule is stole.”

In “Atomic Supernova,” a little boy squints up at a sheriff in the blacktop desert sun, awed by the uniform and the tin star and the gun, hero worship in his eyes. The sheriff’s deadpan reply says a good deal about the state of American justice:

“Are you the good guy?” Stevie asked.

“I’m the only guy,” the sheriff said.

John Wayne is dead and these days a sheriff is far more likely to be found turning an indigent family into the street than hunting down bad guys. For so many, the sheen of the American dream stands burnished far less bright than once it was. Country noir no longer looks like so alien, nor quite so hidden: it looks a whole lot like reality.