Craft

NEW GENRES: Domestic Fabulism or Kansas with a Difference

Let’s coin a phrase: let’s name a certain kind of fiction that creeps and crawls and sometimes does backflips among its respected realistic brethren. Let’s call it domestic fabulism. Just the phrase is new, mind you (and it is; I Googled it); the genre itself has been in use for years.

But what is it? William H. Gass (not a fabulist but certainly an alchemist) claims,

“Readers begin by wanting to be anywhere but here, anywhere but Kansas,”

but in domestic fiction we find ourselves back in the noplacelikehome — and yet. It’s Kansas with a difference.

To explain further requires some exploration of the terms. Fabulism, often interchangeable with magical realism, I’d suggest incorporates fantastical elements within a realistic setting — distinguishing it from fantasy, in which an entirely created world (with constructed rules and systems) is born. These fantastical elements are often cribbed from myth, fairy tale or folk tale. Strange things happen and characters react by shrugging: animals talk, people fly, the dead get up and walk around. Time operates sideways, nature behaves mysteriously;

fabulism feels like the kind of dream in which you look down and realize reality has forgotten its pants.

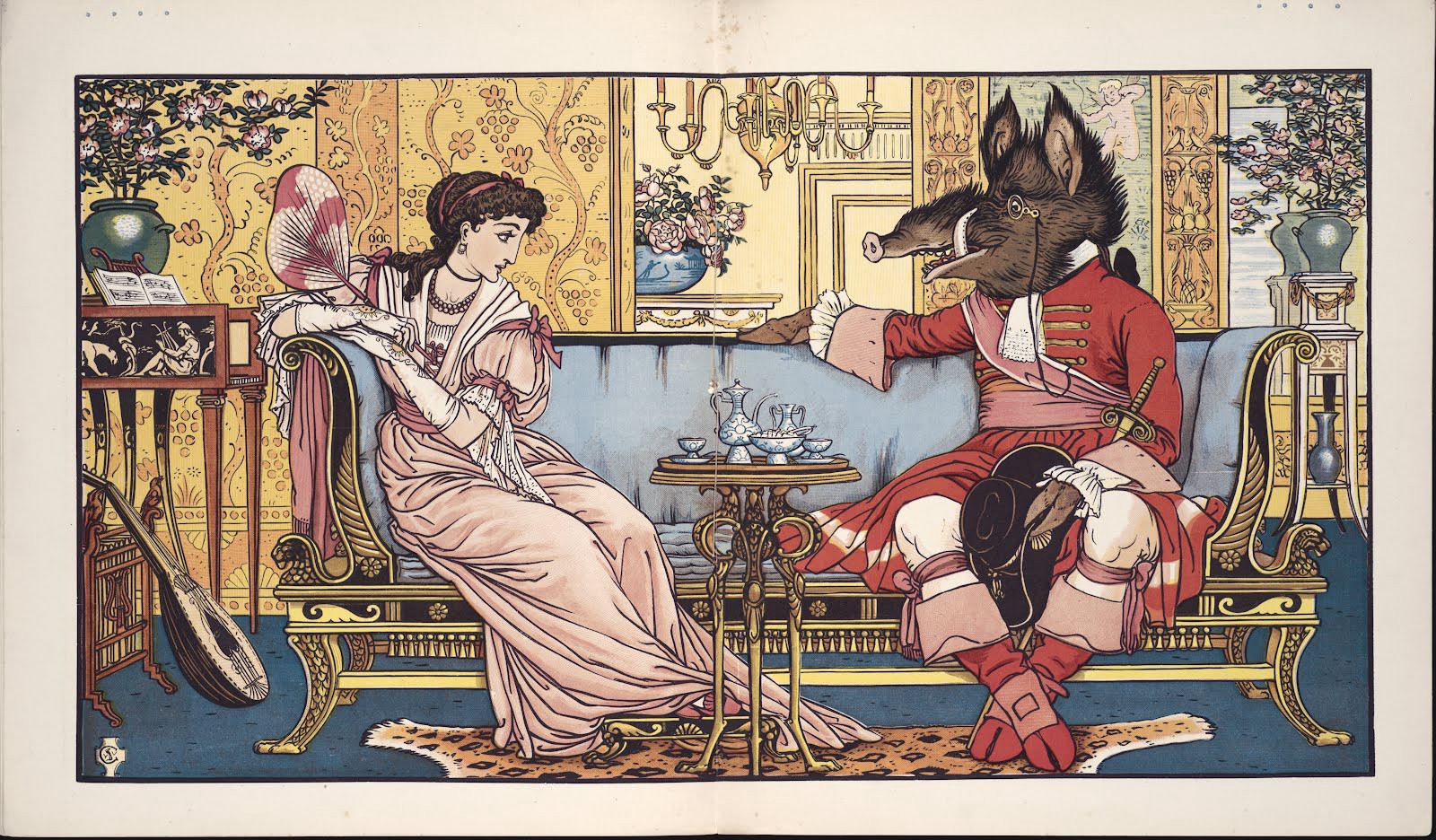

And because of these things, fabulism tends toward the exotic, the historical, the once-upon-a-time, the far-flung. Saramago and Rushdie create worlds where the unthinkable has happened; Dinesen reports back from centuries and countries ago, from castles, counts and courtiers; Angela Carter gives us new-old fairy tales from long ago.

But domestic fabulism takes the elements of fabulism — the animals that talk, the weather that wills itself into being, the people who can fly — and pulls them in tight, bringing them home. Domestic fabulism uses elements like a magnifying glass, or rather, a funhouse mirror. It simultaneously distorts and reveals the true nature of the home, the family, the place of belonging or, in many cases, not belonging at all.

The definition of domestic fiction is interesting, is slippery: Google it and you get results like “women’s fiction,” or “sentimental fiction.’” One must accept, of course, that women are traditionally linked with hearth and home — if absent, that absence is also notable. However, these fictions are, like any insightful writing that involves family, usually anything but sentimental. A.M. Homes’ May We Be Forgiven, Paula Bomer’s Baby, or Yates’ Revolutionary Road all come to mind, not to mention most anything Jonathan Franzen — who I’m guessing would chafe at being called a sentimentalist — has written.

But of course the “sentimental” label springs from the source: the home. Because the home, that square roof and smoking chimney the hero returns to, is women’s to keep: the home is where the mother, sister, daughter, wife waits patiently in traditional literature. Women many hundreds of years ago told stories to each other: instruction, warning, entertainment — and mostly male scholars listened in, took those stories, transformed them — and created fairy tales. But of course the domestic is not some special place or province of the woman, not anymore, and certainly not in my definition. In Roald Dahl’s books, for example, while the stories are often about family, the children are the focus of the transformation, the domestic magic — in ways that often have nothing at all to do with mothers or sisters or wives, present or absent.

In short, I think of the domestic more as fiction about the family and the home, and how it shapes or transforms us.

This is not a new concept — it started with folk tales and later fairy tales themselves. And indeed, from the start, domestic fabulism vs. what I’ll call adventure fabulism were separated. Folk tales gave birth to domestic fabulism — they’re about the married couple, the peasants, the simple farmer. They often do not end happily, since they echo and foreshadow real life, and real life was nasty and brutish for medieval women and their families. Fairy tales, the precursor to adventure fabulism, were literary, were written, were about travel and kings and princesses and evil fairies, about far off lands, battles and trials and nearly always (but not guaranteed until Disney) contained a happy ending. Of these two, domestic fabulism is by far the more grim. Adventure fabulism may be deadly serious in subject matter, but it’s still escapist by way of abandoning the familiar landscape. In Oz, Dorothy may encounter doubles of her farmhand friends, but she doesn’t face the feelings she has, or doesn’t, for the rundown Kansas farmhouse and the dreary tornado-torn earth. She may learn valuable lessons, but from magicians! From witches! From lions and tin men and flying monkeys and the magic of Cinemascope!

There is horror and wonder, but it’s once upon a time — it’s not lurking on our doorstep. We can shut it out.

Domestic fabulism, on the other hand, is immersion, an exploration of self and situation — of the dread that lives and lurks at home, where we cannot escape it. It creates a double existence, an anxiety that ends, if it does, in a sort of forced catharsis — we must confront the thing that lives in our house, in our marriage, in our family, in our town — the succubus that sits on our throats when we dream. Domestic fabulism, it seems to me, is also on the rise. And that makes sense — that in an age beyond the age of exploration, in an age where the exotic has become the familiar — we might once again look to the fabulous in the small minutiae of our daily home lives. We live in an age of dread and anxiety — harm can come to us at any moment; we live in absolute awareness, where domestic stakes are higher than they’ve ever been. It’s a perfect time to turn ourselves inside out by turning the world around us outside in. As Jack Zipes says: “the very act of reading a fairy tale is an uncanny experience in that it separates the reader from the restrictions of reality from the onset and makes the repressed unfamiliar familiar once again.”

But how does domestic fabulism operate? How does it create this tension, this deeper exploration of the places and people we are from? Kate Bernheimer refers to something that Dryden called “the fairy way.” She adopts this phrase for her use and looks at it something like this:

“The fairy way is a non-representational way; it is a short cut between experience and knowledge.”

(Bernheimer makes the distinction between the fabulist and the fairy tale, and of course I agree, but I use her useful writing here on fairy tales since I think the fairy way is largely the fabulist way, or at least a stream running into the same river.) “In his books about the art form of fairy tales,” she continues, “my aesthetic and ethical guru Max Luthi extolls the virtues of fairy tales through the techniques by which a dynamic universe is constellated to such a heightened degree that all things inside of the story exist on a plane so grammatically balanced — so symmetrical, so mirror-like to itself — that its contents are sublimated into a vapor of bliss. From this sort of story no reader can escape unchanged back into the world outside of the story, which to the story — and thus to the reader — does not really exist. “

In other words, these stories leave us on the other side of the looking glass — only, in domestic fabulism, Alice never leaves that interior room, the mirror image of her own small universe. And neither do we — trapped, claustrophobic, we must live shoulder to shoulder with the uncanny. Kelly Link’s “Stone Animals” is a brilliant example of this sometimes miraculous, sometimes terrifying mirror world, as is Bruno Schultz’s The Street of Crocodiles. Blake Butler, in There is No Year, devotes an entire book to the idea of the uncanny copy family. And Kafka’s The Metamorphosis might be the most nightmarish example of all, with a narrator trapped in his home, reduced to beetle form and forced to relate to his family as an estranged, alienated stranger. Aliens among us, indeed.

Many domestic fabulists focus on the ironies and horrors of modern domestic life, conveyed flatly through the use of almost deadpan magic or bent reality — think Joy Williams’ “Congress,” where a lamp with deer feet takes on the job of closest kin, or Helen Oyeyemi’s Mr. Fox, where female characters spring off the page and, alarmingly, charmingly, into the middle of a marriage. Matt Bell’s Cataclysm Baby reflects the anxieties of modern childrearing through a series of moving stories about otherworldly children and parents. And George Saunders, who seems the king of domestic dystopic fabulism, gives us “Sea Oak,” which uses a rotting re-animated corpse to viscerally illustrate the sad breakdown of the American blue-collar home. Furthermore,

Can Xue seems to me in some ways one of the purest inheritors of the Bruno Schultz/Kafka surreal strain, where the uncanny vibrates like a plucked violin string with every story told, every relationship examined, every cat and married couple and home swimming in fantastic uncertainty.

Sometimes Kansas is just that — a city or a town, beyond the scope of just one family. Some domestic fabulists, like Louise Erdrich, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Mo Yan, or Isabel Allende, hold the mirror up better when it’s large enough to reflect back a village. Sometimes the soul of a family is in the soil they stand upon.

Sometimes the domestic crosses rivers and continents with the diaspora, bringing home and family to new lands, redefining the terms. Some of the best new writers are working that angle, bending the immigrant family story through a fabulist lens, like Salvador Plascencia, Porochista Khakpour, and Junot Diaz. Even Karen Russell is writing the domestic fabulist immigrant story in her tale “Vampires in the Lemon Grove,” which despite its wild trappings is a story about a longing for family and for a real home.

And perhaps one of the most interesting things happening in domestic fiction is the subversion of that term “women’s fiction,” of that original domestic space. Joyelle McSweeney writes phantom babies and revolution babies and salamander babies, subverting expectations of motherhood. Aimee Bender takes that traditional women’s space, the kitchen, and endows it with power and danger, gives her book a narrator who tastes emotion in food. Molly Gaudry, in We Take Me Apart, plays with fairy tale tropes and stands them on their heads. Kate Bernheimer, the maven of the contemporary fairy tale, reexamines the role of women and their happy-ever-after expectations in her trilogy about the sisters Gold. Sarah Rose Etter’s twisted, surreal tales drop koalas from the sky like storms, but not for the sake of just weirding us out. Like all of these tales, they seek to tell us something about family — in Etter’s case, it’s often about daughters and fathers, flipping the filial sense and yet making it filigree beautiful.

More and more young authors seem to be using fabulism freely in their domestic fiction, probably in part due to the growing distaste for genre snobby and the blurring of firm genre lines.

Perhaps it also reflects the unease of our own unsolid times, surrounded as we are with unwelcome reminders of what we were and will someday be — like in one of Calvino’s Eusapia, where the city of the dead so exactly imitates the city of the living that the residents can no longer tell who is living, and who is dead.

Indeed, there’s no place like home, but these domestic fabulisms help us mirror home so carefully we’re sure to see and shudder at the slowly spreading cracks.

***

Where to Start: There are way too many books and stories to list here in full — including many of the examples I’ve given here — but these are a good starting point to get the flavor of the genre in its purest form.

- Bruno Schultz The Streets of Crocodiles

- Kelly Link Magic for Beginners

- Mo Yan The Garlic Ballads

- Blake Butler There is No Year

- Matt Bell Cataclysm Baby

- Kate Bernheimer The Gold Family Tales (trilogy)

- Molly Gaudry We Take Me Apart

- Helen Oyeyemi Mr. Fox

- Franz Kafka The Metamorphosis

- Can Xue Blue Light in the Sky and Other Stories