Books & Culture

NEW GENRES: The Worm in The Apple Tale

by Rebecca Scherm

[Editor’s note: New Genres is a recurring feature that aims to complicate and expand our conception of literary genres and their always porous boundaries.]

The plot goes like this: the first time the family meets the worm, they are charmed. “What a charming young man,” one of them might say. But someone else will notice something off about the worm, an awkwardness they can’t pinpoint, but more often than not they will brush off this feeling as their own unfairness or prejudice. After a few more unexpected run-ins (“What are you doing here? How lovely to see you!”) they welcome the worm into their lives fully. In no time at all, they can hardly remember life without the worm.

Of course, the family doesn’t know the worm is a worm yet — except for possibly one doubter, one naysayer, who can’t brush off the feeling that something about the worm is not right. But whenever the doubter expresses concerns, they are dismissed by the others as jealous, petty, or paranoid. By the time the others realize that the doubter was right all along, it is too late. Their whole apple is rotten.

By the time the others realize that the doubter was right all along, it is too late. Their whole apple is rotten.

Gilbert Osmond in Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady is a classic worm, as are Shakespeare’s Iago and smarmy Uncle Claudius, who has wormed his way through the apple before Hamlet even begins. Not every betrayer is a worm. Short-term con artists are not worms. Spies are not worms because they’re working for larger interests than their own. To be a worm, the character has to slowly, steadily munch its way into a relatively healthy apple with little to no initial resistance, becoming harder to exterminate with every single bite.

My earliest encounters with the worm plot must have been fairy tales and Disney movies, where the worm is often a wicked stepmother. I didn’t give it any specific thought until, after writing my own novel, I was often asked about books and movies I found particularly influential and, connecting the dots, saw the worm-in-the-apple picture emerge. Now, it thrills me to recognize a worm plot, to see the soft, browning tunnel left behind as the worm disappears deeper into the apple. The worm-in-the-apple plot feeds our appetites for intrigue and suspicion, but against the backdrop of the most banal events in our lives: hiring a babysitter, meeting the new neighbors. The worm-in-the-apple plot rewards the recreational paranoia of the comfortable. It’s about two common fantasies in conflict: one dream of having it all — a happy, comfortable, fulfilling life — and the nightmare of not being believed, of recognizing a threat and being repeatedly discredited by your loved ones.

Now I’ve become a collector of these worm plots. Here, an introduction to the ways of the worm:

Classically Murderous Worms

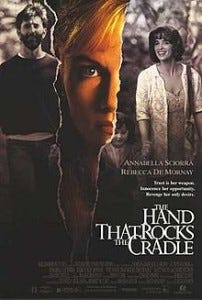

“Peyton Flanders” in The Hand That Rocks the Cradle

I saw this movie at thirteen years old and still can’t shake the quietly horrifying image of “Peyton” secretly breastfeeding the heroine’s baby in the middle of the night in an effort to sabotage her. Rebecca de Mornay, with her puffy blond bangs and shirts buttoned up to the neck, is an ideal worm, sunny and icy in equal measure. Cradle (directed by Curtis Hanson) feeds on both the parental fear of someone turning your children against you and the fear of seduction-by-nanny, cloaking them in pulp horror.

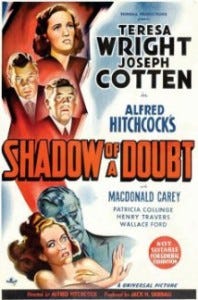

Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt

The Hitchcock classic begins with bored teenager Charlie wishing for something interesting to happen to her family. Soon enough, her beautiful, dapper Uncle Charlie, “merry widow strangler” on the lam, shows up bearing fine jewelry for all. Poor Charlie is the only one who knows his secret, but she’s not quite a naysayer: she’s too worried that this revelation will upset her mother to tell anyone the truth.

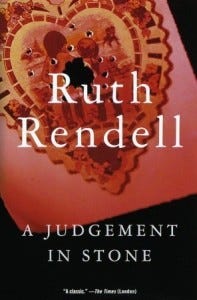

Eunice Parchman in A Judgement in Stone by Ruth Rendell

In this perfect, chilly novel, the Coverdale family hires a new housekeeper, Eunice Parchman, who gives everyone the willies, but they are all too embarrassed by their own class snobbery to fire her. Then, seething with hatred for the Coverdales’ bourgeois habits, Eunice murders them all while they watch opera on television. What’s unusual about Eunice as a worm is her lack of charm: no one likes her. Instead, they pity her or are frightened by her in ways they are ashamed to admit.

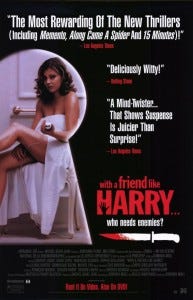

Harry Belastro in With a Friend Like Harry…

In this French film by Dominik Moll, a bizarre encounter in a gas station bathroom introduces Harry, a wealthy man of leisure and “solutions,” into the lives of Claire and Michel, the harried parents of three young children. Harry just wants to help out wherever he sees a problem: first, a new car when theirs is in the shop; later, murder. Claire and Michel are both uncomfortable with his gifts and attention but simply too exhausted to stop it, and Harry’s “solutions” become bloodier with each passing day.

[Redacted] in The Fever by Megan Abbot

I can’t tell you who the worm is without spoiling it, but how many of us remember the betrayal and distrust we felt as teenagers when our friends made new friends without us?

The Worm’s Side of the Story

Denise Lambert in The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen

Jonathan Franzen loves a worm plot, and for the reader, Denise is an unusually complex worm. For one, she gets to tell her own story. We understand, as she tears Brian and Robin first apart and then to shreds, that she is not a monster out to commit evil. She’s a real and screwed-up person, carrying around a lingering shame and the cramp of only-daughter expectations. She’s not only destructive, but self-destructive. Whether readers sympathize or “forgive” Denise is immaterial: here, comically and painfully told, is the worm’s own tale.

David Axelrod in Endless Love by Scott Spencer

David is a stalker and an arsonist. In obsessive teenage love with Jade Butterfield, he worms his way into her family, and in trying to prove his worth, begins to destroy it. With every desperate, self-serving corrective decision David makes, he hurts himself and the Butterfields more. The first thing people mention when Endless Love comes up is either its seventy page sex scene or the two disastrous movie adaptions of it, but those who love the novel prize its intensity, relentlessness, and its fearlessly naked examination of one tragically well-meaning worm.

Tom Ripley in The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith

In Patricia Highsmith’s novel, Tom Ripley is a sociopath who charms first Dickie Greenleaf’s parents and later Dickie himself. He worms his way into Dickie’s world with a mixture of compliance and desperation. Highsmith’s novel has not one but two doubters, first Dickie’s girlfriend, Marge, and then his friend Freddie Miles. One doubter is converted to the charmed, the other is killed; such is the way of worms. But Anthony Minghella’s 1999 film adaptation gives us, instead, a deeply yearning and pitiful Tom who unsettles us not just because we fear a someone like him could enter our own lives, but we because we also feel terrifying empathy for him.

Wait, who’s the worm here?

Freedom by Jonathan Franzen

A Friend of the Family by Lauren Grodstein

In Freedom, Franzen looked at the worm story from another angle: Patty Berglund thinks her son Joey’s girlfriend Connie is the worm destroying her family, but it’s easier for her to see Connie as a predator than to sharpen her lens on Joey or herself. Similarly, in Lauren Grodstein’s A Friend of the Family, we feel our sense of blame and danger shift: at first we understand New Jersey doctor Pete’s disturbance when his aimless teenage son, Alec, starts hanging out with Laura, the newly-returned adult daughter of estranged family friends, ten years Alec’s senior and frighteningly beautiful, who has done something so apparently terrible that no one can say what it is. By the time we do know, our natural sympathies with the narrator are more than strained. Who is in danger here, and who is the monster in this family? What if the worm we fear isn’t the worm at all — it’s us?