Books & Culture

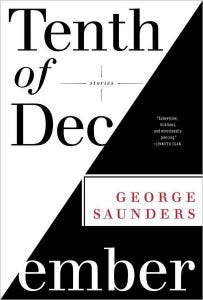

Review: Tenth of December, by George Saunders

A new collection of devastating stories from a master of the form.

If you’ve read any George Saunders at all, you’ll know that his fiction orients itself around a few precepts: people are good; their impulse to surmount their worser selves is inviolate and unflagging; and they can, in fact, be saved. Martyrdom comes up a lot. So do guilt and death. Saunders writes stories that go out of their way to send up religious conventions even as they contain in them the impulse towards religion. People are often rising up out of their bodies and telling us about it. People often come back from the dead. In the meantime, someone, in some strange place, is roasting consumerism, bureaucracy, and a culture laden with stupidity. Saunders’s universe is not pretty, though it is funny. And most of all: it is moving. Especially as it appears in his latest collection, Tenth of December. While some of the fiction here trucks in the high jinks we’ve come to associate with a Saunders story — the crazy venues and vocations — many of the stories break new ground, even as they reprise some of Saunders’s more familiar obsessions.

Four stories in particular stand out: “Victory Lap”; “Home”; “Puppy”; and the title story, all of which are devastating, and, for Saunders, uncharacteristically straightforward. “Victory Lap” is about two kids in the throes of adolescence, struggling with the big questions that consume adolescence: are people good or bad? Does goodness prevail? How am I perceived by the world? In this story, as in “Tenth of December,” we see characters whose inner lives are made prismatic via the competing voices in their heads egging them on in multiple directions. The kids are riddled with anxiety about how to do the right thing and in fact, we see many of the characters in this collection struggle with the same problem. What’s at stake here — and, I’d argue, throughout all of Saunders’s work — is moral fortitude and forgiveness and how these qualities can be mobilized in the effort to be good — a good parent, a good kid, a good person.

Consider “Puppy,” in which a mom and her two kids go to some rundown neighborhood to buy a new pet. The story gradually releases information — a Saunders specialty — that lets us know that the mom was neglected horribly by her own parents and is thus disposed poorly towards rearing her own kids. Her son is violent; her daughter is spoiled, but never mind, all this occasions a good laugh en famille, or so mom tells us. In sum, there’s something horrible about what’s transpiring among these people, though it’s just a premise for a story that launches us into the mind of the woman selling the puppy, whose son has some kind of mental disorder such that she takes drastic and ostensibly abusive measures to restrain him. So remember how mom number one and her kids seemed in bad shape? They’ve got nothing on mom number two. Except, as it turns out, mom number two is just as hell-bent on loving her kid and protecting him as mom number one. And herein lies part of what makes Saunders such a good interpreter of people: he’s got one of the most refined and sensitive empathic facilities of any writer I know.

Not convinced? I refer you to perhaps the most harrowing story of the bunch, “Home,” in which a vet comes back from “the war” (Which war? Aren’t there two?) to find his life changed in all the wrong ways. He’s got babies and an ex who’s living with a new guy; a sister who’s doing just fine with a baby of her own; and a mom who’s just been evicted. Everyone thanks him for “his service” but has no interest in actually serving his needs. Maybe he has PTSD. He’s certainly got some rage. What he doesn’t have is a place to be — a home — because for being off somewhere fighting for a cause no one’s interested in, you end up a man through whom “runs the power of recent dark experience.” The story manages to be funny and grim and expert at crucifying us as readers for our smugness, complacency, and lip service towards vets as they try to reenter their lives.

As for the title story, what can I say? Just read it. It is beautiful and haunting and sad. But like all the fiction in this collection, it also testifies to the good in people, which we tend to dismiss as boring on the page and rare in life. But not so here. Not at all.

Tenth of December: Stories will be released on January 8, 2013.

MORE: “Should we hyphenate ‘pre-boner’?”: George Saunders’ style sheet

***

— Fiona Maazel is the author of LAST LAST CHANCE, and forthcoming, WOKE UP LONELY.