Books & Culture

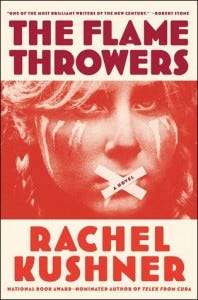

Review: The Flamethrowers, by Rachel Kushner

by Bonnie Altucher

A flamboyant take on velocity, art and New York in the ‘70s

Through the 1970s New York’s revival houses typically offered double features, four-hour orgies of art films and B movies, plus malted milk balls. It was always jolting to emerge afterwards on the derealized street, still optically drenched in Pickup on South Street or Red Desert. Rachel Kushner’s hallucinatory second novel, The Flamethrowers, is as engulfing as those old-school double features, demanding to be read in heedless jags and drowning out life for a while afterwards.

Reno, a recent art school graduate nicknamed for her hometown, lands in downtown Manhattan in 1975, a place so “alive with people my age, and so thoroughly abandoned by most others that the energy of the young seeped out of the ground.” Her squalid first tenement apartment is as “blank and empty as my new life, with its layers upon layers of white paint like a plaster death mask over the two rooms, giving them an ancient urban feeling.” The youthful fantasy of starting fresh as a free, ahistorical self is one of many “masks” to be torn away or shattered in The Flamethrowers.

What’s Behind the Green Door? This tagline for the famous ’70s porn film recurs as a refrain as Reno drifts through New York’s funky, enigmatic streets, searching for her point of entry. She falls in with a louche Soho crowd attuned to her tomboy appeal and willingness “not be the person they had to stop and explain things to.” Reno’s new acquaintances are an unstoppable pageant of intensely original types, revealing themselves in honed facets, their ironic role-play often wittily self-deconstructed. These are party girl/waitresses, cutthroat gallerists and artists who speak in scintillating fugues, beguiling more than they enlighten. Kushner is a monologic genius, periodically freezing the action for madly authoritative ten-page arias that neither violate mimesis nor relinquish their hold on our attention. Similarly, Kushner’s descriptiveness lingers over every available surface, playing with illusion and transparency as in this alluring account of a wrong-headed act of vandalism: “The trees on Tenth Street reflected on the windshield of the parked Cadillac like a leafy silkscreen before Burdmore shattered its glass with a sledgehammer.” (Burdmore is a street-fighting East Village anarchist who has just taken revenge on the wrong person’s Cadillac.)

Part of the novel’s obsessional power lies in the multiplicity of ways it reformulates very basic questions, such as what is the depth of a surface? And what is our relationship to time? In one of the most spectacular chapters, Reno rides to the Bonneville Salt Flats to race her teal flake Valera motorcycle over the blinding white terrain as an experiment in land art, the mark left on the salt by her bike intended as a literal drawing of her exploit. At 148 mph, she says, “I was in an acute case of the present tense. Nothing mattered but the milliseconds of life at that speed.” Her ensuing wipeout feels all but inevitable, the entire episode a high-octane mise en abyme concentrating the narrative of Reno’s lost illusions, and demonstrating the impossibility of life in an unmediated present.

Like Kushner’s first novel (Telex from Cuba, a 2008 National Book Award finalist) The Flamethrowers is set against a background of simmering class-war refracted in collaged omniscience, with no single character fully grasping what’s at stake. This is the best kind of historical fiction, imagined in eye-popping detail, inhabited by protagonists who seem be making their fateful decisions in real time. Reno’s story alternates with that of the rise of the Pirelli-esque Valera motorcycle- and tire-manufacturing empire. One especially powerful segment, told from the point of view of a Brazilian Indian rubber-tapper indentured by the Valera tire company, ingeniously switches to second person so as to implicate the reader in the tragic subjectivity of the anonymous tapper at the moment he decides to make a fatal run for it. “If you step on a branch by accident the trees give away your secrets.” Slave labor is the repressed secret of the Valera fortune; likewise, the family’s trophy estate at Lake Como is haunted by its slippered household staff, who “didn’t knock, or announce themselves, but…acted invisible, meant to dust or replace dead blooms as if they themselves were of no consequence to the privacy of others.”

Reno’s trajectory coincides with the Valeras’ when she moves in with Sandro, a minimalist sculptor living in elegant, self-imposed exile in Soho. When Reno catches him in a crass infidelity, she flees to Rome, swept into a faction of the Red Brigades, a coalition of striking factory workers and student sympathizers. The creakiness of this particular plot twist is redeemed by the exhilarating switch to a context of populist upheaval and Kushner’s visionary touch with scenes of epic flux. In a tear-gassing, “a hissing bloom of smoke filled the street…. it was like being in a cloud that had moved down over a mountain, the vertigo of not knowing which direction is falling and which is up.”

In Rome, Reno briefly encounters a charismatic agitator named Bene who makes feminist pirate radio broadcasts. “Sisters,” warns Bene, “men connect you with the world, but not to your own self.” I was hoping for Reno’s voyeuristic relations with other female characters to connect; instead she returns to Soho, where her alienation intensifies. If this is Kushner’s way of showing the feedback loop through which female competition reinforces patriarchy, the regression was still disconcerting. Embittered, Reno tries on a pose of macho disregard, thinking, “Maybe women were meant to speed past, just a blur.” She never commits to an identification with other women.

Then again, in the open, reverberant style of some of the best seventies movies, this is a novel that ends on the word “question.” Reno is now perhaps ready to make her own mark as a young female artist. And what’s behind the Green Door? Naked people wearing masks, real sex as surreal performance. And when the city drops its mask on a hot night in July, 1977? “You have to believe in the system,” says Reno, “to feel it was wrong to take things without paying for them.”

The Flamethrowers (Scribner, 400 pages) will be released on April 2, 2013.

Recommended if you liked: Fugitive Days by Bill Ayers, Sentimental Education by Gustave Flaubert, Laurie Anderson, Trisha Brown, Gordon Matta-Clark: Pioneers of the Downtown Scene, New York 1970s by Linda Yee

***

— Bonnie Altucher writes fiction in Manhattan. You can find her here.