Books & Culture

REVIEW: The Storm at the Door by Stefan Merrill Block

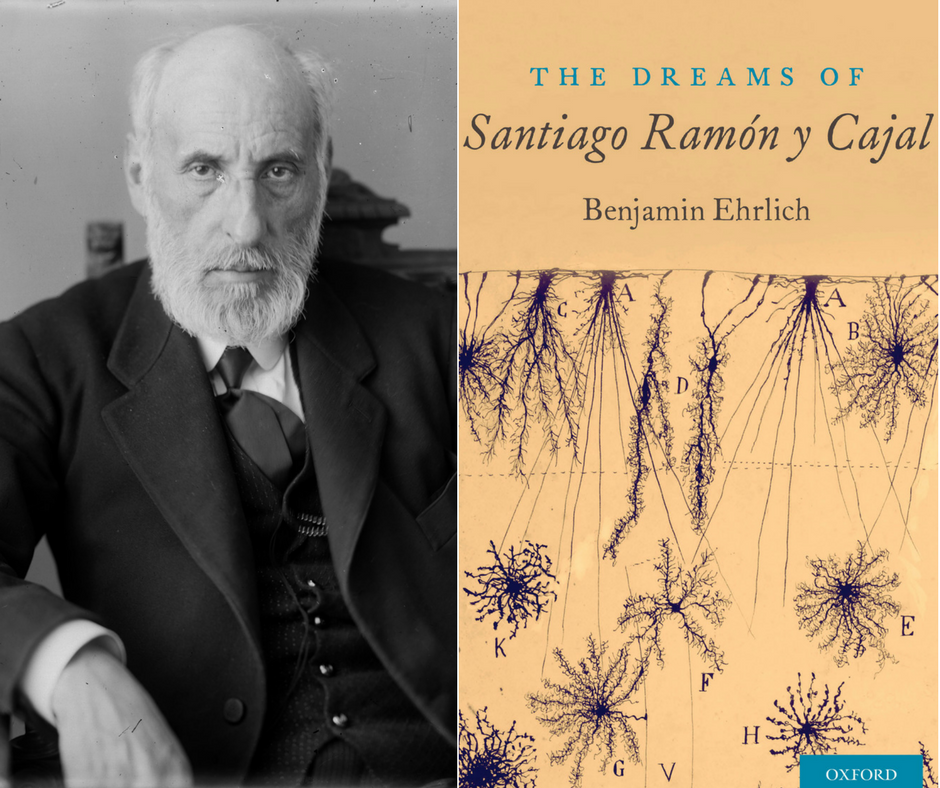

The Storm at the Door

by Stefan Merrill Block

Random House

368pp/$25

It has been said that fiction writers tell lies to discover the truth. And of course these lies (and these truths) are not random; we choose to illuminate and magnify things that haunt us, obsess us, things that, at first, we don’t understand. We create fictions in order to understand ourselves, the world and our place in it that much more completely.

Stefan Merrill Block takes this idea to the extreme in his new novel, The Storm at the Door. In it, he fills in the blanks of his own history by telling a fictionalized version of what his grandparents, Katherine and Frederick, went through in the 1960s, when his grandfather was institutionalized for bipolar disorder. The story is based in fact: the institution was, in real life, McLean Hospital (renamed in the book as The Mayflower Home for the Mentally Ill), which is known for its list of famous patients, including mathematician John Nash and poets Sylvia Plath and Robert Lowell.

The story is told in chapters, each with its own ominous-sounding title (“We Must Always Be Vigilant,” “The Vast Unknowable”) and title page that features a photo of both Block’s grandparents, with one portrait larger than the other to indicate whose viewpoint the following pages will belong to.

In Katherine’s chapters, we come to understand her reasoning for keeping her husband in the hospital, as well as what it was like living with him before. True to Bipolar’s symptoms, Frederick is portrayed as a man of extremes: charming and effusive one moment, oversensitive and bewildered the next. We also learn, and moreover, we understand, what it is like to have a husband in a mental hospital in the 1960s: suddenly finding oneself a single parent, the whispers and glances, the lonely sort of celebrity that this kind of tragedy lends. And we are not limited to Katherine’s head alone; the novel’s point of view moves effortlessly into that of their children and even some of the townspeople.

Author Stefan Merrill Block

But it is in Frederick’s chapters that Block really excels. Occasionally, in Katherine’s point of view, Block merely explains, but in Frederick’s we really become. We come to understand the complicated emotions; how on one hand, Frederick feels that his hospitalization is unjustified, but on the other, he is overwhelmed by guilt for his failures, incapable of curtailing his darkness. As in Katherine’s chapters, we are not restricted to Frederick’s point of view. We hear from hospital staff and other patients. In this ability to dig deeply into the minds of multiple characters Block’s talents shine through. Although he is young, Block has no problem diving into the minds of men and women, the young and middle-aged, crazy and sane, creating characters that are fully-realized, and, although flawed, very much sympathetic.

Block’s writing itself is enviable, as well. Full of great images, complex metaphors, and sophisticated language, he manages to dazzle throughout the book. Unfortunately, strengths can be weaknesses as well: sometimes a metaphor reaches too far, sometimes he uses a GRE word when an SAT word would do, sometimes his wordy, complex sentences left me exhausted with their brilliance. But this seems like a quality that will be curtailed with age and experience. Don’t get me wrong: Block is definitely an author to watch.

Of course, it is difficult to discuss mental hospitals in the 1960s without thinking of One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and Block’s and Kesey’s novels certainly share similarities: hospital staff with questionable intentions, brutal treatment, even escape plans. But Block’s work is his own. The staff may be borderline evil, but their carefully-nuanced inner lives save them from being cartoonish. And in The Storm at the Door, the moral lesson (if there is one) is much more ambiguous, as it is in life. Moreover, Block’s work is overlaid with sensitivity, empathy, and a delicateness, perhaps because the subject matter so heavily embedded into his own history and subconscious.

–Julia Jackson writes fiction and is a regular contributor to Electric Dish. She has an MFA from Brooklyn College.