Books & Culture

Revisiting Jurassic Park’s Tangled Bookish Roots

If you’re walking into the brand-new Jurassic World totally ignorant to the whole history of the Jurassic Park franchise, you might not believe me when I tell you that this frenetic summer blockbuster was actually born from a strange mishmash of cinematic and bookish origins. In the reality of the Jurassic novels and films, geneticists recreate dinosaurs by combining their DNA with other creatures or, as in the new movie, splice genes to create an uber-badass dino. But the existence of Jurassic Park as a massive cultural phenomenon is also the result of the splicing of both literary and filmic sensibilities. Here are a few essential details to help understand Jurassic Park’s unique narrative heritage.

Jurassic Park Was a Screenplay First, Then a Novel, Then a Screenplay

According to numerous interviews, Michael Crichton’s initial idea struck him in the early 1980’s. The best-selling novelist conceived of a story featuring cloned prehistoric creatures as a screenplay first. In this proto-version of Jurassic Park, a graduate student would create a genetically perfect pterodactyl in a lab. Now, it’s good to remember that it wasn’t super weird to think of Michael Crichton writing screenplays in the 80’s, nor was he any stranger to having his novels adapted into films prior to his success with Jurassic Park. His 1969 novel The Andromeda Strain was adapted into a 1971 film of the same name. (That movie’s screenplay was written by Nelson Gidding and directed by Robert Wise. Wise has the bizarre reputation of having directed both The Sound of Music and Star Trek: The Motion Picture).

But Crichton did his own screenplays too! In 1973, he both wrote and directed the movie Westworld about a robot-theme park populated by robot cowboys. The robots of this theme park end up going berserk and start killing people. Sound familiar? The point is, understanding the success of Jurassic Park (the film and the novel) starts with understanding that Michael Crichton was already a major power player in both publishing and in Hollywood way before 1990 happened. When he decided to turn Jurassic Park into a book and center it around a theme park of dinosaurs instead of his grad student in the lab, he sent an early draft of the book to his friend Steven Spielberg. Jurassic Park was optioned to become a film before Crichton even finished writing it. If you think the book occasionally read like the prose version of storyboards, there’s a reason for that.

There are A LOT of Character POVs in Jurassic Park and Many Terminate When the Character Dies

Probably the nightmare of many MFA professors, Jurassic Park features multiple close-third person POVs; easily more than ten! This includes everyone from John Arnold (Samuel L. Jackson in the movie) and random lawyers to characters who only appear for a second at the beginning of the novel, like a few scientists in a lab at Columbia University, a little girl on vacation on an island, and a nurse in Costa Rica. Once the novel gets going, the characters we stay with the most are the paleontologist Dr. Alan Grant, young Timmy, and often Jurassic Park badass Muldoon. In the film, this character (played by Bob Peck) is best remembered as the guy who says “clever girl” right before the raptors take him down.

While it’s not intended as a joke, the book does a weird job of giving us glimpses of many characters’ thoughts right before being killed by a dinosaur. These sections are odd, and it’s as though Crichton wrote the scenes to end with the words “and then he died,” but always deleted those words right afterward. The death of the villainous hacker Nedry is easily the best close-third-person death scene:

“Nedry fell to the ground and landed on something scaly and cold, it was the animal’s foot, and then there was a new pain on both sides of his head. The pain grew worse, and as he was lifted to his feet he knew the dinosaur had his head in its jaws, and the horror of that realization was followed by a final wish, that it would all be ended soon.”

Yet for whatever reason, Crichton decided not to give us any POVs with a dinosaur. Why, Crichton? Why?

Michael Crichton’s Book Sequel — The Lost World — Was Encouraged by Steven Spielberg and Retconned His Original Novel

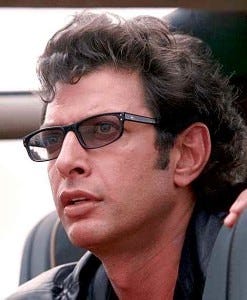

In the original Jurassic Park novel, the cantankerous chaos-theory-loving mathematician Ian Malcolm takes forever (pretty much half the book) to “die” after he’s severely wounded by a T-Rex. If you’re wondering why Jeff Goldblum sits around and sort of hangs out doing nothing but being laid up in the movie, that’s because the movie is a fairly close adaptation to the original book’s plot. Any reading of the novel tells us that Ian Malcolm does die in the book, but in a Conan Doyle-esque move, Crichton never gave us the body of Ian Malcolm. This allowed Ian Malcolm to be brought back to life in the second Jurassic Park novel, The Lost World. Here, Malcolm claims to only have been “partially” dead. Crichton didn’t really want to write a sequel to Jurassic Park, but was apparently encouraged by Spielberg, which probably led to the novelist retconning the death of this well-liked character. Just like with the formation of the first book, the world of cinema has always influenced the Jurassic Park novels.

Though the plot of Crichton’s The Lost World differs from the Spielberg sequel to Jurassic Park (called The Lost World: Jurassic Park), it’s still similar enough to be considered an adaption of sorts. Spielberg, however, added the idea of a T-Rex terrorizing San Diego into the end of the movie, a plot element not present in Crichton’s book. However, the idea of a dinosaur loose in a major city is probably a homage to the 1925 film version of The Lost World — itself an adaptation of a Sir Arthur Conan Doyle novel — in which a captured brontosaurus gets loose in London. This detail does not exist in the novel version of Conan Doyle’s Lost World, which instead featured an escaped pterodactyl in London, albeit briefly. The point is both Lost Worlds — Doyle’s and Crichton’s — have famous film adaptations which tack-on a finale featuring giant big dinosaurs on the loose in a major city.

Two of Jurassic Park’s Major Characters Are Specific Analogs to Real People

In both the novel and film versions of Jurassic Park there are dueling Doctors, one of mathematics (Dr. Malcolm) and one of paleontology (Dr. Grant). No matter what you might think of this story, the existence of these two characters is part of what makes the book (and film) work at all. In fact, the brand new Jurassic World actually suffers considerably from a lack of realistic scientific characters. Our beloved Dr. Wu from the original film and novel is actually bizarrely re-imagined as a mad-scientist villain in the new movie.

But in the book, Wu is a solid geneticist, Grant a calm paleontologist, and Malcolm an eccentric mathematical theoretician. Despite an occasionally slap-dash writing style of switching POVs constantly, Crichton does manage to bring out real voices from both Grant and Malcolm. And this was probably because there’s a considerable amount of reality in the DNA of these fictional people. According to Crichton, he based Alan Grant on prominent paleontologist Jack Horner. Meanwhile, the “chaos theory” which pervades Ian Malcolm’s ideology was derived from the real-life physicist Heinz Pagels. We tend to think of Dr. Ian Malcom only as Jeff Goldblum now, and in the novel, he’s very similar to Goldblum’s performance insofar as he’s eccentric and flippantly brilliant, though a little less flirtatious than his cinematic counterpart. Physically, he’s not Goldblum really at all. Meanwhile, the descriptions of Dr. Grant in the book sound more like Jeff Bridges as “The Dude” in The Big Lebowski than calm and sexy Sam Neil from the movie we all remember.

Jurassic Park is Bizarrely Both Pro-Science and Anti-Science at the Same Time

Throughout Jurassic Park, Ian Malcolm rants and raves about chaos theory and how science has failed mankind. His basic assertions are that science hasn’t made life any easier and has in fact made things worse. He says a lot of this while he’s laid up and pumped full of shitloads of morphine. It’s in these rants we get the idea that scientific progress is “rape of the natural world,” a line used in the original film. A lot of these assertions hew fairly hyperbolic, and it seems like Crichton intends for Malcolm’s ideas about science to be over-the-top, almost as an exercise in contrast. In the movie, Malcolm’s views are broadly reduced to Frankenstein-esque hand-wringing about “playing God,” but the book is both a little more subtle than that in some ways, and goes much further in others. Vacillating somewhere between cautionary tale and contemplative science fiction, Malcolm gets this nice speech in the second half of the book:

“You may create many of them [dinosaurs] in a very short time, you never learn anything about them, yet you expect them to do your bidding, because you made them and you therefore think you own them; you forget that they are alive, they have an intelligence of their own…”

This bit of philosophy didn’t make it into the 1993 movie, but an almost word-for-word version of it appears in Jurassic World, this time spoken by the hunky raptor-tamer Owen Grady (Chris Pratt).

Interestingly, despite Malcolm’s anti-science rants, Jurassic Park is a novel founded in science and explanations of science. Crichton often digresses to discuss what was in 1990, cutting-edge paleontology. The evolutionary link between birds and dinosaurs wasn’t common knowledge, and public perception of dinosaurs as slow and dumb was still, partially, the norm. So, through Grant, Crichton geeks out about the newish dinosaur theories. On the technical front, he’ll even give the reader a few pages of computer code to realistically convey what kind of hacker-conflicts John Arnold is facing at the hands of Nedry.

The pure research Crichton poured into the book encounters an interesting and somewhat insane push-back from Crichton’s own creation — Ian Malcolm — who is seemingly there to make fun of Crichton’s research and the science that makes the book tick in the first place. And it’s in this conflict where you can find Jurassic Park’s real soul. Sure, it’s a book about cloned dinosaurs running amok; that’s obvious and awesome. But it’s also a book that seems to be having a discussion with itself about the nature of discovery and how that relates to the power of creation.

But it’s also a book that seems to be having a discussion with itself about the nature of discovery and how that relates to the power of creation.

Even Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein isn’t an as on-the-nose “Frankenstein’s monster” story as people might claim. And Jurassic Park is similar. For all the “cautionary” aspects of this unique novel, its ultimate theme seems to exist more in a state of ponderous concern, alternating pleasantly with spectacular moment of sheer awe.