interviews

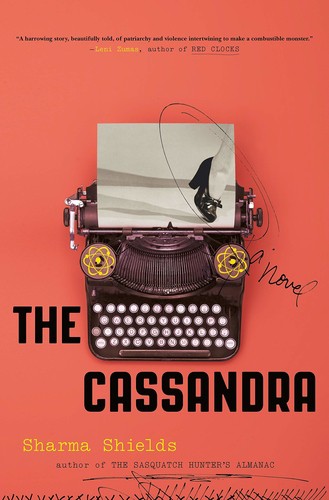

“The Cassandra” Is a Novel about Toxic Masculinity and Cursed Women

Sharma Shields’ novel is a call for us all to truly think about who we are — and who we are becoming.

Summoning references to classic Greek myth, The Cassandra, set in the 1940s, focuses on the life of Mildred Groves, a young, unusual woman who sees visions of the future. When an opportunity for employment at the secretive Hanford research center presents itself, Mildred leaves home and enters a totally new world — one she sees as a hopeful land of possibilities. But there’s much more than possibility lurking in the dark corners at Hanford.

Dissecting humanity’s cravings for power and our fascination with destruction, Sharma Shields’ The Cassandra is a call for us all to truly think about who we are — and who we are becoming.

Bradley Sides: In your latest novel, The Cassandra, you mix magical realism with myth. You present a young woman named Mildred Groves, who very much reflects Cassandra from mythology. Mildred, like Cassandra, sees horribly bleak visions of the future that no one believes. What was the genesis of your novel?

Sharma Shields: The setting of Hanford came first, before I considered Mildred or Cassandra. When I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis five years ago, a couple of people mentioned the high incidence of MS in the Inland Northwest, where I grew up and live now, and someone said to me, “It’s because we’re downwind of Hanford.”

I’d been thinking of writing a gloomy Northwest version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and it occurred to me after I heard this that Hanford was the perfect setting.

Early on in my research about Hanford, I was surprised to read that virtually no one working there in 1944 had any idea what they were manufacturing. There was even a rumor floating around that they were producing toilet paper for the troops overseas. When I took a tour of Reactor B in the summer of 2015, I marveled at the irony of the vintage signage everywhere, “Loose lips sink ships,” “Safety first,” etc. Secrecy and safety were the paramount messages, but of course this is a place that contributed to more than 100,000 deaths in Nagasaki; a place that has poisoned our local environment and caused numerous thyroid cancers, birth defects, and polluted crops and water. The irony there is remarkable.

As I mused on all of this violent secrecy, I thought of Cassandra and the Trojan war, “the shambles for men’s butchery, the dripping floor.” And from Cassandra sprang Mildred Groves, who hails from Omak, a small town near where my mom grew up (Okanogan) in arid central Washington State.

BS: From the start, Mildred is such a complicated character. She’s driven. She’s strong. She’s loyal. I was rooting for her all the way, but I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that I also found her to be frustrating, especially after she gets settled in at Hanford. What do you hope readers take away from her after reading her story?

SS: Mildred is frustrating, probably in a lot of the same ways I frustrate myself. She’s eager to please (to a fault), she’s naïve, she internalizes the behavior of others, she’s willing to put herself down to make someone feel better. The way she accepts and makes excuses for the verbal battery of her mother and sister is alarming.

Mildred does what a lot of us do, suppresses herself until that negative energy bursts out of her, and the wrong people get hurt. She does awful, incalculable harm. It parallels the harm our country has done to others; the harm humanity does to itself. By the end of the book, she is utterly changed, physically, mentally. I hope readers find something relatable in her struggle and in her complicity and fallibility and regrets, but also in her power and her attempt to enact change. I wanted her to be both: powerless, powerful, like we all are. I’m hoping Mildred expresses a sharp warning about how we treat ourselves and treat others on both an individual and global scale.

BS: Men certainly aren’t the only ones who mistreat Mildred (her mother who continually calls her a “ferret face” has to be mentioned), but they are the most consistent in doing so. They are truly awful to her — even from the first chapter when she has her interview at Hanford. They harass, abuse, and devalue her. Nevertheless, she persists. The Cassandra feels timely.

SS: Both women and men in this novel are capable of cruelties large and small. Many of the characters turn violent and commit horrific acts, including Mildred, but you’re right, this is a novel about the prison of militant nationalism and toxic masculinity, and how those confines really in the end harm us all, regardless of gender.

Many of the interactions between men and women in the book are taken directly from my own life: critical comments issued about female bodies, unwanted attention, a sense of never truly being safe, patronizing treatment, and even assault and rape. Someone very close to me in my own family, a woman I love and admire and look up to as being one of the hardest-working and strongest humans I know, was put in the ER by her own husband. He dangled one of her sons over a balcony in their large house, he beat her senseless. I remember keenly when my parents received the phone call about her hospitalization. I was in grade school. I remember listening to their hushed, upset voices, and how endlessly dark the night sky seemed through their bedroom window. How could someone do this to another human being? That man was a radiologist; he ended up losing his Washington State medical license for abusing patients, but he’s practicing again in Idaho.

I was working on a new draft of this book when Trump said his “grab them by the pussy” comment, and what I felt — what a lot of women felt — was actual physical pain. It was hard to breath, my lower body ached, and a hurtful memory from when I was 14 began to plague me. For years I’d told myself that what had happened was my own fault, but I was approaching 40 now, and it was ridiculous to keep deceiving myself in this way. My mom arrived one day when I was working on one of the most violent scenes in the novel, and she could see I was agitated, depressed. I told her I didn’t know what I was doing to myself, writing in these dark places, and pulling from events I’d never let myself fully articulate to anyone, let alone myself. My mom suspected what was happening to me at 14 with this older boy, and we’ve now had open discussions about it. At the time I assumed it was all my fault, but it was not. It’s also bigger than being just that boy’s fault (he, like Kavanaugh, was 17 at the time): Something societal needs to change. I poured a lot of these emotions and memories into the book. 1944 really isn’t that far away. A lot has changed, and very little has changed, too.

Trump’s presidency has not caused more misogyny or racism or ignorance, the way some people think. It’s a product of it. This has been in our country for a long time, this white nationalism and misogyny. He is the poster child for it now (and he’s a child in so many ways, behaviorally); he represents a staunch portion of the population unwilling to open their minds and evolve. My own personal belief is that the humanities can teach us how to become better people. But I also see the naiveté in such a statement. Are we broken beyond fixing? I’m not sure. I hope not.

The Cassandra also became unexpectedly timely when Hanford started popping up in the national news again, this time for leaking nuclear waste tanks and, most recently, for attempted shut downs of Hanford watchdog groups. Now that I’ve researched Hanford, I’m not surprised by any of this. We’ll be feeling the direct repercussions of Hanford’s creation in our region and country for a long time, environmentally and ethically. When the administration gloats about funding nuclear programs and major defense/weapons programs, I cringe. We are setting ourselves up to destroy more, when what we need is repair.

This is a novel about the prison of militant nationalism and toxic masculinity, and how those confines in the end harm us all, regardless of gender.

BS: It’s early in the year, but these lines have to be some of the most sobering I’ll encounter throughout 2019:

“The things we’ve done to the children of this world — slavery, brainwashing, exile, genocide — do any other creatures harm their children this way? These deviances built our own nation, they’ve built all of the civilizations of men. I awoke with the certainty that none of us deserved to be alive, myself least of all.”

I know we’re technically dealing with fiction here, but this feels as real as it gets. How difficult was it to admit something so haunting about our species — and ourselves?

Sharma Shields: I grew up very sheltered from the truth of our history, regional and otherwise. In school, we learned the Whitman Massacre in Walla Walla was a “thoughtless tragedy,” rather than a retaliation of the Cayuse for being systematically murdered by the Whitmans and other settlers. Hitler was talked about as an anomaly, as if genocide wasn’t occurring here, or wasn’t occurring worldwide at that very moment. Slavery was also a thing of the past, not to concern ourselves with, and when I asked someone in my family about it, they said we shouldn’t beat ourselves up for what our ancestors did.

I’m of the other mindset: We should beat ourselves up for what we’ve done. What we should not do is draw a line between our present selves and our history; the two are inextricable. It is easy to be lazy, complicit. So easy. I’m guilty of it even as we speak. But we are educated humans, capable of imagination and empathy and hopefully social evolution. By acknowledging our darkness, our propensity for violence and greed and cruelty, maybe we can begin to imagine shedding it for something less harmful. Is such evolution possible? I really don’t know.

It’s been upsetting for me to see the ways in which children, especially, are harmed in this world. Having children now, I read the news and I’m gripped by a profound sadness for the joy and love we are shuttering. Native girls and women are missing and/or dead, children are separated from their parents on the border, a girl on the Pakistan/Indian border is tortured to death because her religion is not the same as someone else’s, children in the public school where my husband teaches are homeless, maybe to avoid being abused again, or because their own parents are in jail, or have abandoned them for drugs. Near and far there is failure. And it’s our failure, collectively.

It may be true that it makes me critical of myself, these thoughts, that I’m always pressing myself to do better, and I’m always examining my own failures of kindness and fairness and compassion (of which there are many, so many). But I’m sick of individualism, of this country with its pull-yourself-up-by-your-boot-straps mentality, a mentality that has never and does not apply to marginalized groups. There was a great article in the New York Times recently about women in politics, about how they must rise as a group effort and not individually. At first I was annoyed that we as women can’t go it alone, but then I realized: Going it alone might be the whole problem. There is hope in unification, in coming together rather than tearing apart.

Now we just need all of us to unify somehow. I don’t know how to do it. I don’t know if I believe we can do it, but I hope so. My novel is intended to be a warning about what will happen if we don’t.

By acknowledging our darkness, our propensity for violence and greed and cruelty, maybe we can begin to imagine shedding it for something less harmful.

BS: You, I believe, are one of our great writers working within magical realism and weird fiction. Whether I’m reading one of your stories from Favorite Monster or exploring the worlds and situations you’ve crafted in your two novels, The Sasquatch Hunter’s Almanac and The Cassandra, you are someone who boldly embraces the fantastic. What is it that attracts you to this genre of writing?

SS: I’ve always felt there was truth in our nightmares and in the unknowable. There is so much we don’t understand about our universe, about our own existence, and crossing into the abstract forces us to confront uncomfortable questions.

I think quite a lot about Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy, which describes how we spend much of our lives distracting ourselves with Apollonian rationality — materialism, schedules, religion, our jobs — but how art and the imaginative can pull back that velvet curtain and reveal the chaos beyond, or what Nietzsche calls the Dionysian spirit. I’m curious about this chaos, about the unexplained, and I’m always startled by the lengths we go as humans to avoid considering chaos and our smallness and mortality. I’ve sort of made it my life’s goal to be comfortable with these uncertainties, and our potential insignificance is comforting to me, how we are no more than this tiny infinitesimal heartbeat in a vast incomprehensible universe. To realize my own smallness shrinks the ego, and along with it shrinks my many anxieties (and being an anxious person, this is a much-appreciated consequence). I can’t help feeling that there is compassion to be found in this acceptance, that if we understood how small our lives truly are, we would be kinder to ourselves and to our fellow humans. It seems that so many problems in our world come from people’s grandiosity and self-righteousness.

I become most enthralled in the writing process when I surprise myself, when I wind up somewhere I least expect. Sometimes this occurs through a character behaving in a way I hadn’t thought they would (a kind person, for example, committing a heinous act), and sometimes this occurs with the arrival of a mythological creature, an enchanted heron or a witch, say, or maybe a fantastical event such as a baby snatched up by an eagle or a bottomless pit opening up in a forest. The last two events take place in my novel The Sasquatch Hunter’s Almanac, and the metaphors they carry with them are incredibly personal to me, as wacky as the plots are: the former a metaphor for postpartum depression and parental anxiety, the latter a reflection on the endless depths of loss and guilt. I love the metaphorical wiggle-room the fantastic allows us. Metaphor is my jam, both writing and reading-wise.

In The Cassandra, compared to my first novel, I wanted the focus to be less on the fantastic and more on the historical, given the absolutely alarming research I uncovered about Hanford. A lot of that shit was weird enough. But drawing the parallel between Mildred Groves and her powerful visions, and Cassandra and her visions from the Orestian trilogy became important to me: These are two women mired in times of war, at the mercy of those more powerful than they are, and their very lives are at stake. They are powerful seers, but cursed to be ignored. The strangeness of her visions served a few purposes for me: It heightens the metaphorical and the emotional in the book; it creates an interesting tension between the very real events at Hanford and the fantastical, a push and pull of reality and nightmare; and it hopefully entertains by discussing history in a way that might be more memorable than reading a dry text book.

BS: There’s an actual Cassandra from mythology, obviously. But you have other elements from history that you channel, too. Hanford research center, the place where Mildred works, was a real place. There are several historical references from World War II. I mean, there’s a lot of real-world connections going on. Were having these historical elements limiting, or did you find them helpful?

SS: I’ve surprised myself by finding a lot of inspiration in real historical events — I never before considered myself a historical writer. I’ve always loved researching, whether for college essays or for my reference job at the Spokane County Library District, so I suppose in a way it was inevitable that research would become a focus in my fiction. In this book, I feel (perhaps erroneously) like almost every detail, down to every line, is connected to something researched. The actress mentioned throughout, for example, Susan Peters: Mildred Groves adores her from afar and talks about her throughout the book, at first in a star-struck way, and then by the novel’s end, more mournfully. Peters was a real star in Hollywood in the 1940s. I found her on a website about the “100 Most Beautiful Women of All Time,” and was surprised to see someone from Spokane (my hometown) listed there. The story I uncovered about her was remarkable: she was injured in a hunting accident and left paralyzed, and she attempted (and failed) to reintegrate into a very ableist Hollywood. Without meaning to, I’d found an interesting parallel to Mildred’s uphill battle against the militant forces at Hanford.

It was one of my favorite aspects of writing this novel, finding historical puzzle pieces like this and arranging them within the plot. It gives the work these interesting layers to peel open, and it helped me draw out Mildred’s character. It was also my way of tipping my hat to Peters, this historical figure who tried to upset the norm in a place devoted to surface-level beauty. For me it was not at all limiting but rather a tantalizing challenge, another way of finding inspiration in the unexpected.

Trump’s presidency has not caused more misogyny or racism or ignorance, the way some people think. It’s a product of it.

BS: I’d like to wrap up by going back to our first topic: speculative literature. What have you read recently that you’d recommend for lovers of all that is magical and weird?

SS: My favorite recent reads include: Wayétu Moore’s She Would Be King, a breathtaking blend of history and magic involving the origins of Liberia; Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream, a surreal eco-nightmare; Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties, a story collection about women’s autonomy/agency and lack of it. I’m very excited to start Marlon James’s new trilogy. I love what he said in a recent New York Times interview, “Genre is such a ridiculous convention, as ridiculous as the idea of the Great American Novel.” He points out as a kid that he was never required to cleave works of literature into separate categories and how weird it is we force people to do that now.