Books & Culture

The Figure in a Field: What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford

The best track on Lucinda Williams’s album Sweet Old World is the song “Pineola,” which describes the funeral for a man who “shot himself with a .44.” Later in the song, Williams sings, “Born and raised in Pineola / His mama believed in the Pentecost / She got the preacher to say some words / So his soul wouldn’t get lost.” That soul belonged to the poet Frank Stanford. According to a New Yorker profile of Williams by Bill Buford, Williams and Stanford met in Fayetteville, Arkansas, in the spring of 1978, and the two had an affair that lasted until his suicide a few months later. Stanford was twenty-nine at the time, and though he had already published nine books of poetry, as well as his 15,000 line epic poem The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You, he was working as a land surveyor. The details of his suicide are as mysterious as they are simple. Stanford was married to a painter named Ginny (Crouch) Stanford, and in addition to his many other flings, Williams among them, he was also having a long-term affair with the poet C.D. Wright (Stanford and Wright together ran the small press Lost Roads Publishers). One day in June of 1978, Stanford came home to find every philanderer’s nightmare: his wife and main mistress in the same room, untangling his web of lies. As Buford tells it, Stanford was so distraught that he drove to procure a pistol, and when he returned home, he went into the bedroom and shot himself.

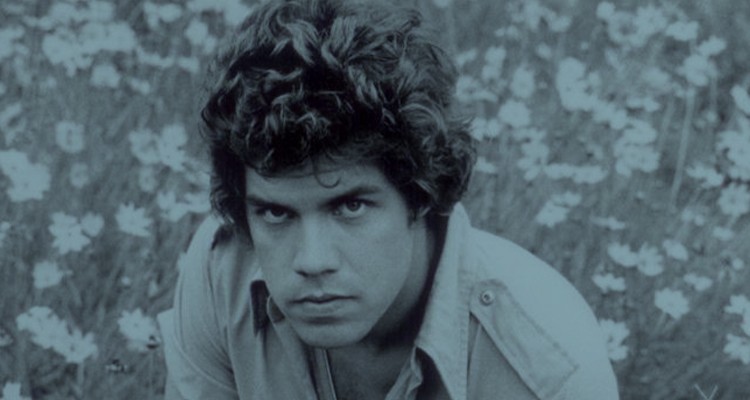

These Byronic details are central to the legend of Frank Stanford, and because there is no definitive biography, other such details — the time in a Mississippi orphanage, a childhood spent exploring the Delta with his adoptive father, the years moving from hotel room to motel room after dropping out of college — are left for his surviving lovers to share. The central motif of all these stories is Stanford’s good looks and charisma; Buford quotes the writer Ellen Gilchrist as saying of Stanford, “To know Frank then…was to see how Jesus got his followers. Everybody worshipped him.” The cover of What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford, published by Copper Canyon Press, features a photograph sure to recruit Stanford more disciples: Stanford, with his curls and boyish features, is crouched in a field of wildflowers, holding a book. The photograph also shows Stanford dressed in jeans and a work shirt, which hints at how Stanford has long been portrayed in the history of American poetry — as a primitive. The poet Dean Young writes in his introduction to What About This: “Many of these poems seem as if they were written with a burned stick. With blood, in river mud.” But Dean Young also points out that Stanford’s swaggering poetry, a poetry that fights only heavyweight challengers such as death and love, stands as a much-needed contrast to our contemporary poetry, a poetry of “rigor and suspicion” that has “deadened the nerves and made poets fear the irrational.” Stanford’s poetry is an American poetry free of what Young calls “a long century of self-consciousness and irony.” What About This contains all ten of Stanford’s published collections, many of them until now out-of-print, as well as a selection of his unpublished manuscripts, an interview, a few prose selections, and snippets of A Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You. Taken together, these 745 pages represent an achievement matched only by Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in the history of American poetry.

In an interview with Irving Broughton, Stanford’s friend and champion, Stanford responds to a question about readers and critics not comprehending his work by saying, “If a person is quiet enough inside he might be able to catch on to what I’m trying to do in my poetry.” However, what makes this collection so remarkable are the feelings that even ten minutes spent dipping into Stanford’s world arouses in the reader, and none of those feelings are quiet. His poems are full of knives and water moccasins and blood; of dwarves and midgets and mysterious riders; of jukeboxes and picture-shows and whiskey. The one image that appears consistently in Stanford’s work is the moon. In a famous early poem “The Singing Knives,” the moon is “a dead man floating down the river.” Later in the same collection, Stanford writes, “The cloud passed over the moon / Like a turkey shutting its eye.” If early collections like The Singing Knives and Shade do suffer from a Rimbaud-like obsession with death, they still contain remarkable individual poems, particularly when Stanford shifts from the narrative to the lyric. The poem “Night Time” from Shade contains the stanza:

When I was twelve I had to

wash my mouth out with soap

for taking the deaf girl to the woods

and holding a lantern

under her dress

The young Stanford dealt with this tension between the narrative and lyric, between the allegorical and the personal, by simply keeping them separate in his early work, but by the time he reached his peak with the collections Field Talk and Constant Stranger, he had combined the two impulses into a unified voice by converting his own history into allegory, by making himself the star of his own myth. The poem “Spell” from Field Talk is a perfect example of this mature voice:

I aimed to get some of my blood

back from the Snow Lake mosquitoes

my belly was full of lemonade

and my hair had Wildroot on it

I took to the thicket at dawn

not knowing where I was from the man in the moon

there were trees with so much shade

you shivered

Likewise, in Constant Stranger we find the same narrative form of his early work, but here Stanford allows for moments of lyrical exuberance inside that form. In the poem “Blue Yodel of the Desperado,” he writes:

I wanted to ride down to where I come from

On an Appaloosa

And take you away for good

I wanted to tie your hands with my belt

And watch you stare at the campfire

In the mountains not saying a word

In the essay “With the Approach of the Oak the Axeman Quakes,” Stanford writes, “We go back to the poetry, the poet. I see a figure in a field. There is genuine moonlight shining on his crowbar. He is prying stumps out of his ground. Poetry busts guts.” This is the exact effect reading Stanford’s best work elicits: that of watching a poet wrench his own personal history into the world. And that work, that effort, just like the poetry it produced, makes the reader sweat.

What about This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford

by Frank Stanford