essays

The Last Holdouts of the Genre Wars: on Kazuo Ishiguro, Ursula K. Le Guin, and the Misuse of Labels

If you’re like me and grew up reading Raymond Carver alongside Raymond Chandler and Marvel comics alongside Flannery O’Connor, you know it is a great time for fiction. In 2015, the walls between genre fiction and literary fiction are mostly in ruins. The New Yorker devotes issues to science fiction and crime, the Library of America collects work by H. P. Lovecraft and Kurt Vonnegut, the National Book Foundation awards medals to Stephen King and Ursula K. Le Guin, and MFA and Clarion grads debate George R. R. Martin and Junot Diaz alike. If you are a teenager now, the concept of the genre wars could feel as anachronistic as cassette tapes and landlines.

Except, somehow skirmishes in the genre wars keep flaring up. Even today there remain holdouts, fighting Hatifled-and-McCoy-battles on blogs and twitter over ancient insults. The most recent argument occurred last week over Kazuo Ishiguro’s latest novel, The Buried Giant. In a New York Times interview, Ishiguro wondered if readers would understand what he was trying to do: “Will they be prejudiced against the surface elements? Are they going to say this is fantasy?” Ursula K. Le Guin, among others, took great umbrage, arguing that not only was the book fantasy, it was failed fantasy: “It was like watching a man falling from a high wire while he shouts to the audience, ‘Are they going say I’m a tight-rope walker?’”

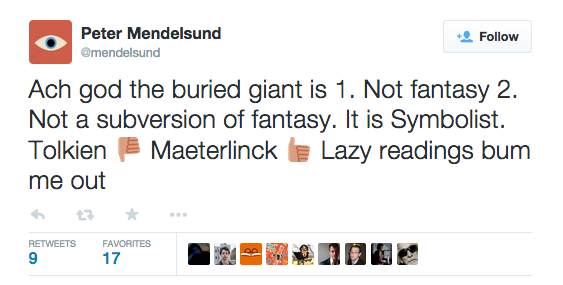

At Salon, Laura Miller wrote about how the book is not fantasy but rather a meshing of modern realism with medieval romance. At Flavorwire, Jonathan Sturgeon agreed: “…The Buried Giant is not a genre work: its inspiration predates fantasy literature. It would be inane, even absurd, to retroactively apply the fantasy label to Homer’s Odyssey because it has monsters.” On Twitter, Peter Mendelsund, who designed the jacket, had yet another label to apply:

Finally, Ishiguro came out to say that he hadn’t meant to insult fantasy: “If there is some sort of battle line being drawn for and against ogres and pixies appearing in books, I am on the side of ogres and pixies.”

As is typical in the genre wars, everyone seems to be talking past each other. The idea that Ishiguro “despises” genre — as Le Guin suggests — seems suspect. In the same interview that sparked the controversy, Ishiguro said that the atmosphere of The Buried Giant was inspired by western and samurai movies; he doesn’t seem concerned if his work is construed as genre. He does seem worried, however, that readers of his previous novels might come to The Buried Giant with the wrong expectations. All writers worry about how their books will be received, and Ishiguro had a similar problem with the science fiction-tinged Never Let Me Go being attacked by some for not being SF enough and by others for being too SF.

I don’t think genre labels are meaningless. Indeed, genres can be vital traditions for writers to work in and draw inspiration from. Genre distinctions are real — genre mash-ups wouldn’t exist without readers being able to distinguish between the genres being mashed — but genre, like so many labels, is better understood as a spectrum than separate boxes. Some works are clearly operating in a specific genre tradition, while others mix different traditions, and yet others simply play with a few elements while doing their own thing.

Part of the problem is that both the genre and literary worlds have incoherent and contradictory definitions of the words “genre” and “literary.” This often leads to a pointless game of appropriation, where literary critics and readers say that the best genre writers have “transcended genre” and should count as literary fiction, while, at the same time, genre fans declare that famous literary writers belong to genres they never considered themselves a part of. Raymond Chandler is “really” literary fiction while Italo Calvino is “actually” fantasy. (The most absurd proprietary claim I’ve ever encountered was a SF fan arguing that Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America — an otherwise realist novel that imagines what would have happened if FDR had lost the 1940 election — was by definition science fiction because all alternative history books are posited on a theory of multiple realities resulting, for some reason I can’t remember, from teleporting wormholes.)

The problem with this appropriation game is that it eschews any understanding of history, tradition, influence, or context in favor of “winning.” It turns criticism into politics instead of a means to better understand and appreciate books.

This is where I think Le Guin — who is one my favorite fiction writers — falters. She simultaneously defines Ishiguro’s work as fantasy, and then claims that it doesn’t work as real fantasy. Well, then maybe Ishiguro was correct all along in saying the label didn’t fit. If Ishiguro tells us his influences were westerns, samurai films, and 14th-century chivalric poems, what does it matter if the result can or can’t be labeled fantasy? Do the labels “fantasy” or “realism” advance an understanding of what he is doing?

Le Guin is right about the literary world having a tradition of genre snobbery. She talked about some of that history here at Electric Literature with Michael Cunningham. There was absolutely a time when genre work was walled-off from the so-called “literary” world, with literary critics and magazines thumbing their noses at certain genres (fantasy, horror, romance) while absorbing others into the canon (Victorian gothic, magical realism, southern gothic). Indeed, even a decade ago — when I began submitting fiction — it was common for literary magazines to openly state they weren’t open to genre fiction and for creative writing classes to disallow vampires and aliens. There are still a few stubborn holdouts, but they are a dwindling group.

But if the genre world has been marginalized, they’ve also walled themselves off. It is just as common to see genre fans call literary fiction “mundane fiction” and scoff at the “lack of imagination” of literary writers as it is to see literary fiction fans assume that all genre fiction is formulaic and poorly-written. Jonathan Lethem had a great essay about the fact that while the literary fiction world erred by not recognizing the likes of Delany, Dick, and Le Guin, the SF world made an equal error in ignoring the likes of Thomas Pynchon, Angela Carter, and Don DeLillo. The ignorance has been mutual.

Fortunately, “has” is the key word here. These battle lines and distinctions feel increasingly anachronistic. Nowadays, Karen Russell writes about werewolves and Colson Whitehead writes about zombies while NYRB reviews A Song of Ice and Fire. Yes, it is harder to win a Hugo if you are thought of as “literary” and harder to win a Pulitzer if you are thought of as “genre,” but we really do live in a time of genre-bending and omnivorous reading. Writers feel increasingly comfortable to write in any genre they desire, as well they should.