interviews

“The Parisian” Weaves Family Stories and Palestinian History Into a Debut Novel

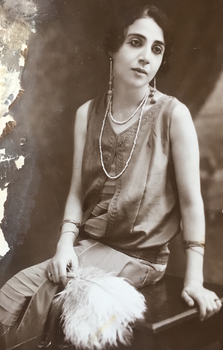

Isabella Hammad on finding fiction inspiration in her great-grandfather's life and homeland

What is Nablus like?

“Nablus is a little village. It’s a town, I mean a city. It’s not large but we call it a city. What I mean is, even when you leave Nablus, you take it with you.”

Midhat Kamal’s response, the main character in Isabella Hammad’s The Parisian, or Al-Barisi is symbolic of the central role Nablus plays in her debut novel. It’s a city and country. Tradition, home and family. Love, loss and memory. Past, present and infinity. Nablus unfolds with history and the stories of each character—the main ones inspired by family stories. She says: “It’s a product of an obsession, in a way. It’s also not any one thing. Even the act of writing about Palestine feels complicated—What does it mean to write in English about Nablus, for example? But it became a kind of imaginative compulsion for me. In the end I think you have to follow those compulsions.”

Isabella Hammad voice echoes like that of a hakawatiyeh or storyteller, in an old coffeehouse in Palestine. But we are in Le Pain Quotidien in Soho. It took Hammad five years to finish the novel, released April 2019 by Grove Press. She was twenty-two years old when she started—after she graduated with an English literature degree from Oxford and before she enrolled in the creative writing M.F.A. program at New York University.

She recounts that the book was like the through-line of her life, it was the thing around which everything else revolved: From the beginning I knew it was going to be long and that it was going to use time in this way. The gulf of time is important in the book in general.

Hammad merges what we think we know and what we have yet to discover about what it means to be Palestinian. The complex characters and storyline, and the colorful and bustling city of Nablus, also known as the uncrowned queen of Palestine, are memorable. The novel begins with the fading days of the Ottoman Empire to British Mandate Palestine, and follows the Midhat Kamal’s journey to France to study medicine, his haunting love story with Jeannette Molineu in Montpellier before heading to Paris, and his eventual return to Nablus.

Despite decades of occupation, Palestinians have continued to contribute to literature, art and cinema globally——from historic Palestine to Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North and South America, where its diaspora lives. They write in multiple languages, have different nationalities, cultural influences, wide-ranging aesthetics, and many belong to other literary traditions and nations. But despite their contrasting experiences, they stem from a place and memory that have marked their imagination; and though they are still separated they are more connected than ever. This debut writer Isabella Hammad, this historical novel The Parisian, is an exciting addition to the literary world stage.

Nathalie Handal: Midhat Kamal is inspired by your great grandfather. How did you deal with the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction?

Isabella Hammad: As many books are, this book was written somewhere in that weird zone where memory meets imagination. It just happens that in this case they weren’t only my memories. Of course, when we make narratives of anything that has happened we are always already dancing with fiction—memory invents, and even history invents, hanging facts on strings of meaning—and so by the time they reached me, the stories of the real Midhat varied pretty drastically depending on the narrator. The result being that there were so many gaps and contradictions in my “research” that it didn’t feel, to me, that there even was a clear boundary between “fiction” and “non-fiction.”

As for broader historical realities, I immersed myself as much as I could in history books and archives and conversations with academics or people who remembered things. Imbibing history like that, your imagination puts flesh on the bones of the past pretty automatically. I tried to reach a point where my knowledge of the facts was organic enough that it could come out of me without much distinction between what I knew, remembered, and had made up. If I was writing an academic book that might be an issue. Fortunately it’s a novel.

NH: Love and nation are interweaved—is love political?

IH: For an American reading something like this, I imagine they will naturally be on the side of the individual over everything else. But for example, the bit in the end when Jamil is critical of Midhat “al-Barisi wandering around with his colored ties”—one reader told me she was shocked to see this external critical image of Midhat, as someone who is not committed enough. It’s actually a very fair criticism of him, though. When you don’t have a nation, you have to be a nationalist. It’s all hands on deck. But everything’s complicated, and we’re all human.

I grew up hearing stories about Midhat, and most of the stories are from the later period when my father and his siblings knew him as their grandfather. They were often about his love for Fatima, which was a real love story. When she was in hospital he was kissing the soles of her little wrinkled feet and said, look at her beautiful feet. It was a real love, and also an arranged one, defined from the beginning by the dynamics of family and class in Nablus, and maybe not always easy, not always ideal.

Nablus has historically been quite stratified in terms of class. There are several main landowning families that have had historically political roles, the Hammad family included. I was interested in Midhat’s family being middle class and upwardly mobile, seeming to have this promise, this economic promise, which is partly why she consents to the marriage but things fall apart.

NH: Can you expand on that?

IH: Nablus has always been traditional and politically engaged and culturally rich, as well as full of contradictions—as most places are when you look closely enough. It’s traditional and yet, for example, some major figures in the women’s movement came out of Nablus. The image of a Nabulsiyeh is a woman who is strong-minded. I was interested in the life of a young man living under the social pressures of a conservative society that is itself under threat, on shaky ground, where everything is uncertain but they are still operating according to this ancient system. What does that mean on a human scale? What’s the fall-out?

The story I was told was that Fatima had an important role in selecting her husband and that’s why they got married. She chose him. It was important to show in the novel that it was not as simple as a man selecting a woman.

NH: Can you speak more about this change: “In Constantinople, his understanding of love changed. The curriculum at the Mekteb-i Sultani exposed him to the poetry of the pre-islamic Jahiliyya and Abbassid verses… and the works of Imru’ al-Qays and the love lyrics and ghazals.”

We think of romantic love as personal but it is intensely social–bound up in family expectations, our communities, and cultural production.

IH: Writing that passage I was thinking about romantic love being constructed by our reading habits – and the construction is always mutual – although maybe nowadays “reading habits” can also include film and tv. It’s one of the things that can vary between cultures. We think of romantic love as personal but in fact it is intensely social and bound up in other things, in family expectations and our communities and cultural production, and, even though novel-reading is mostly solitary, I do think of literature as fundamentally social. Novels are a pretty late addition in the history of literature. So that passage follows Midhat progressing from having a very childlike bond with a little girl to a more adolescent understanding of romance which is essentially couched in fantasy—coinciding with when he becomes literate. And then he meets an actual woman he likes, feels very confused, and things change again. Books can only get you so far, after all.

Midhat undergoes changes throughout the book, and I also think of him as a person who struggles with change. There are many things you could say the book is “about”, of course, but one of them is the psychological development of a man very sensitive to instability, living in chronically unstable environments.

NH: Did you read Arabic literature?

IH: My mother is a big reader and she fed me the English classics when I was young. I read Arabic literature a bit later and with pleasure and astonishment—among the first novels were probably Tayeb Saleh’s Season of Migration to the North and Anton Shammas’ Arabesques. Maybe those influenced me, I don’t know. Certainly the very earliest “texts” I was exposed to, if you can call them texts, were the oral stories.

NH: What is your relationship with the Arabic language?

IH: I don’t speak it perfectly. I speak it with my father and family members, and I did a lot of my interviewing in Arabic. But I’m shy. The spokenness of Arabic and rhythm of spoken Arabic were important for me to include in the dialogue. It seemed natural for me. There is a particular way Arabs speak to each other that you can’t translate directly into English, so I wanted to give a flavor of the sounds, and what they do rather than what they mean.

I did not grow up reading and writing and made efforts to learn. I’m reasonably fluent.

NH: For most Palestinians, the first visit to their ancestral city is a major moment—moving, memorable, a metamorphosis. Tell us about your first journey to Nablus.

IH: I didn’t know what to expect. I’d been to Lebanon and Jordan but this was different. It is one thing to be passionate about Palestine in the diaspora without going, and another thing to go and see. It had always been my intention to go. I was planning to go after university. I went in 2013. It was an exhausting trip. My grandmother and I crossed the bridge. They kept us for a long time at the border. When we finally arrived in Nablus, we met so many people, endless relatives. Engagements everyday.

NH: What surprised you?

IH: The mountainous-ness. I had an emotional reaction to it. I insisted on going walking. There is something about the way the land just comes up at you. Something about being close to the earth. The landscape moved me in a way I can’t express. It sounds like a cliché but I had a visceral reaction to it.

Nablus is beautiful—beautiful buildings. I spent a lot of time with architects. The Hammad house is still standing and features heavily in the novel.

NH: Where is it?

IH: Near the center, next to the English hospital. You can often see it from afar because of its three peaked windows, it’s the Levantine style. A couple of years ago I went on the top floor for the first time. And it’s now a circus school, there were kids doing back flips. Exquisite molding. When I first went downstairs, years ago, they sent a little boy to accompany me. I opened the cupboards and found photographs of my grandmother and relatives from the 30s and 40s.

NH: What are the differences and similarities between the Nablus during the time of the British mandate and pre-WWII Europe, which the novel is set, and the Nablus you know today?

IH: It depends on which “then” we’re talking about. Comparing Nablus now with Nablus before the 1927 earthquake, for instance, there will be major architectural differences, since so many of the old buildings collapsed. 1948 was another massive shift, because the influx of refugees changed the city’s dynamic, and determined what happened during the intifadas.

I think the quality of engagement among young people is maybe something that marks off the present time, given the town’s history as a locus of political organization. My cousin says that if as a young person you want to get involved in politics nowadays you should move to Ramallah. In a way, that’s understandable. During the early 2000s, Nablus was ringed with checkpoints and unemployment soared, and economic hardship can do a lot to dampen engagement. But it can also have the opposite effect, as we have seen elsewhere. In any case, these things are never permanent and an atmosphere can change on a dime.

NH: And what is the same?

IH: The soap factories, the old coffee shops, the street vendors. The heart of old Nablus is still there, in the valley, on the mountains, in the old books.

NH: Is there an object that reminds you of Nablus?

Nablus has always been traditional, politically engaged, culturally rich and full of contradictions.

IH: There is an old map of Nablus, made by a French man. It’s outdated and has the railway line. Made in the 20s. I love his spellings. I once used it to navigate Nablus, to see the differences.

Nablus is important in the book and I didn’t grow up there so I always visit it. It became a Nablus of my imagination. I spent so much time reading and thinking about the town it would feature in my dreams.

NH: Where in London did you grow up?

IH: In West London, in a neighborhood called Acton. It was kind of suburban so as kids we played outside. It was fairly diverse. For secondary education, I went to a private school, which wasn’t as diverse. London is highly class-based and at the same time, there is a sort of mingling of ethnicities that I don’t see in New York in the same way. That’s something London has to offer that’s really wonderful. I hope it continues, as we are in a worrying moment in England.

NH: Did you grow up identifying as British or English?

IH: We were British. But my mother is Irish English and my father is a Palestinian who grew up in Lebanon. Palestine was important to us growing up. My grandmother was involved in the Palestinian community in London. She has worked for many years with several charities.

NH: Did you question your identity?

IH: I didn’t grow up feeling consciously embattled about my identity, but as a child I was also in a pretty multicultural environment anyway. There were always people of different nationalities in the house. The Palestinian cause was always important.

NH: Is living in the United States what you imagined?

IH: I thought I knew America because I had seen American television shows and films. I also thought it would be more similar to England, because of the language. At first it was pretty alien to me, and I found I was always looking for subtext when people talked—in England there is always subtext. There is also subtext in America, it just took me longer to recognize it.

NH: What is your gaze on the new generation of Palestinians?

When you don’t grow up in Palestine, Palestine becomes an imaginary place, maybe problematically so.

IH: Palestinian society has the potential to be one of the more progressive Arab societies. The pressure of Palestinian identity as a collective overrides sectarian and geographic divisions ultimately. You can see it particularly in the young generations. There are attempts to connect and be unified. Which is promising. There isn’t much to be optimistic about but this is something I feel we can be.

NH: Can you speak about what your obsession feels and sounds to you, what secret and desire have you given it?

IH: When you don’t grow up in Palestine, Palestine becomes a—maybe problematically—imaginary place. So it begins with a sort of an imaginative fixation for me, as it does for many others. I suggest problematic primarily because I think that if, after lots of idealizing and nostalgia a Palestinian from outside does manage to go back, the reality of the situation can be a bit of a shock. I am interested in all of that, all of the problems of it, both ethically and emotionally but also from a standpoint of sheer curiosity. Obsessions grow new obsessions. What does it mean to be inside or outside? Where exactly is inside? We say inside to refer to Palestinians living in 48, but I’m sure they experience their fair share of feelings of being outside. What about Gazans, are they locked in or locked out? Both, I suppose; that’s partly what it is to be imprisoned.

As for secrets and desires, those are things not to be shared.

NH: What’s your song?

IH: Firstly, storytelling. I grew up around a lot of stories. Everyone in my family is an amazing storyteller. My grandmother can tell stories for days. Her stories are weapons. The other element is language, and expression, self-expression. There is a particular pleasure from language that I do not get from anything else.