interviews

The Problem Of Language: A Conversation With Christian TeBordo, Author Of Toughlahoma

Christian TeBordo is an enigma. He is a beloved figure in the world of indie literature, a station he has cultivated with a minimal web presence. In an age where even major writers are being asked by their publishers to create social media accounts, TeBordo is free of not only a Twitter account and a Facebook author page, but even a website. As a devotee of social media, I can’t help but sit in awe of his discipline, or perhaps sheer indifference.

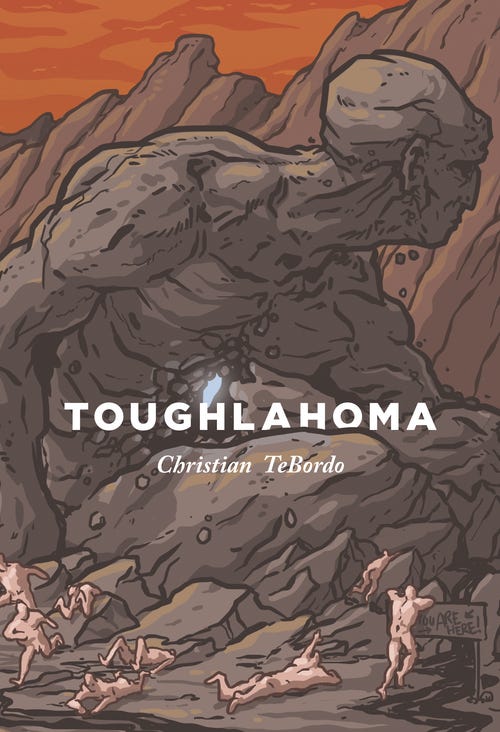

But all this also cultivates an air of mystery, with news on TeBordo’s writing difficult to come by. He is the kind of writer I google every couple of months to see if a new story has popped up somewhere, or if some publisher has announce they are publishing one of his books. His existing books have been equally mysterious, not just in their stories and forms, but in their meandering releases. His first novel, The Conviction and Subsequent Life of Savior Neck back in 2005, two years later he returned with two more novels, Better Ways of Being Dead and We Go Liquid. Three more years went by before his story collection — and breakout — The Awful Possibilities arrived. Now, after an even lengthier wait, we have been graced with Toughlahoma.

Even if I hadn’t already been a fan of TeBordo’s work (having read some of his stories around 2008, I tracked down a copy of We Go Liquid and fell in love with the oddball story of a boy who thinks his deceased mother is sending him messages via spam email), I would have been sold on Toughlahoma just because of the title. I preordered the book the first day it was available. When it arrived I devoured it nearly in a single sitting. It was one of the more baffling reading experiences of my life, sending my brain reeling between the inventive use of language, pop culture, and religion.

TeBordo and I have been in touch off and on for years now, and I’ve always felt honored by those opportunities to speak with him. After reading Toughlahoma I knew I had to ask him about the book, and while my questions became more akin to dissections, he dove into them with gusto.

RWB: This is one of the few books I’ve read that I find indescribable, at least in terms of plot. Yet I can come up with lots of strange descriptions of the style. One of them being a perverted re-appropriation of Bible stories and I think this is the best place to start. The book frantically rips apart biblical mythology, not particular stories per se, but the kind of stories, the following of a message from a reality-ambiguous source, the offering of icons and sacrifice, etc. In a way it almost seems like an indictment of how the Bible warned against so many of the things it spawned, idol worship, for example. So I have to ask what your relationship to Christianity has been during your life and what you were trying to explore in this acid trip-esque deconstruction of the Bible?

I experienced a lot of beautiful things growing up in the church, and also a lot of terrible things…

CT: Damn, Ryan — this is about as complex a first question as you could ask me, and I could probably fill this whole space and more with an answer, but let me try to keep it concise. My relationship to Christianity is as complicated as anyone’s, I guess. My parents were both Presbyterian ministers and they sent me to Baptist school when I was very young and I was ordained an elder before I was old enough to drive. I also studied religion and theology at both the undergrad and grad levels. I experienced a lot of beautiful things growing up in the church, and also a lot of terrible things, and it would be too easy to go into them here as a way of explaining my approach to the world, which is that there are beautiful things and terrible things and some of them are both, and I realized this early on. Studying religion academically helped me to reconcile that. The religion department at Bard, where I did my bachelor’s in something other than religion (we didn’t really have majors), had an interesting approach to comparative religion, which was that they focused on the differences between major religions and the sects within them rather than the commonalities. I think being aware of differences is more interesting and healthy than steamrolling everything to pretend we’re all the same. So there’s that.

But then, Toughlahoma has much less to do with religion than it may seem to. Yes, it was inspired by the Bible (as well as ancient epics and mythology and proto-novels of the renaissance and enlightenment eras) but these inspirations were more structural and psychological than ideological. The best brief explanation I can make comes from Erich Auerbach’s book Mimesis, the first chapter of which contrasts the mimetic styles of Homer and the writer(s) of the Old Testament:

“Abraham, Jacob, or even Moses produces a more concrete, direct, and historical impression than the figures of the Homeric world — not because they are better described in terms of sense (the contrary is the case) but because the confused, contradictory multiplicity of events. The psychological and factual cross-purposes, which true history reveals, have not disappeared in the representation but still remain clearly perceptible.”

Auerbach says this fairly objectively and without a real qualitative judgment, but what it suggests to me as a contemporary fiction writer is that what we think of as the psychological complexity of, for example, the modern novel (a strawperson, I know) with its focus on interiority, is potentially a drastic oversimplification. The example that always comes to mind — and I’ve used this in interviews before — is of DFW’s story “Girl With Curious Hair.” I love the story, which is about an amoral yuppie manchild doing bad things with his punk friends. But at the end of the story there’s a brief flashback to him being abused by his father, which, to me, is such a copout with regard to the complexity of the character that it’s not only unfair to him (which is fine; he doesn’t exist) but an insult to people, not categorically, but to the individual who would read the story looking for something about what it meant to be a person at that point in history.

Contrast this with the first two chapters of Genesis, which contain two distinct creation stories, one proto-Platonic and one about digging in the dirt and blowing on noses. And then in the next chapter the whole thing goes to shit when Adam and the woman eat the fruit and they hide because they realize they’re naked, and the Lord pretends he doesn’t know where they are, why they’re hiding, who told them they were naked. In my reading the Lord’s being ironic, but the situation is doubly ironic because there’s no story until they eat the fruit they’ve been forbidden to eat, just two people eating the boring fruit in peace for eternity. All happy families are alike. So the idea behind Toughlahoma was an old one — that contradiction and juxtaposition and irony might generate something like a plot, or at least real complexity — and attempted with full respect and admiration for the Bible. So if anyone reading this knows anyone at the Gideons, please convince them to place a copy in the top drawer of the bedside table in every hotel room on the planet after purchasing directly from the good people at Rescue Press.

RWB: For me, I saw the book as a sort or re-appropriation, or a remix, if we want to get more modern. There’s a running theme in the book, a phrase that is repeated, “the problem is language.” This, too, feels like a take on how people come to interpret stories. When you think about this phrase, you start to realize there are infinite problems with language, starting with the fact that we are often divided by communication gaps due to languages, literacy levels, etc. And that’s to say nothing of how differently two people can interpret the same sentence. When you’re writing a book so centered on the problem of language, so playful in its use of language, how do you reconcile with the reality of interpretation and understanding, or do you simply accept it and move on?

CT: I would say I “accept it and move on.” That’s my public answer at least. On the most basic level, the level where I say something like “it’s raining,” and the person standing next to me will know what I mean, assuming it’s raining when I say it, the prose in Toughlahoma and the events it describes is pretty clear. For all the syntactical weirdness, I think anyone reading in good faith should be able to understand what’s happening.

The question of why it’s happening gets you closer to what I mean by the problem of language, the first level of which is that, it seems to me, the existence of language alters, or maybe invents, the concept of “happening.” If you go back to the paragraph above where I say to someone else,”it’s raining,” that’s a different experience from two people just standing there getting rained on, especially when those people don’t have a tool with which to say “it’s raining.” I know it sounds like adolescent stoner logic, but for me the introduction of language does something problematic before we even get to issues of misinterpretation or willful deception or demagoguery (although it makes all of those things easier to utilize). I think language itself ironizes actuality, and written language ironizes spoken language, and so on. One way of dealing with this is to pretend the problem isn’t there, to pretend irony is a thing that can be rejected or set aside. Another way is to call attention to it in direct and indirect ways to see if you could maybe find a provisional answer for the problem in the spaces between where the words are, what one of the narrators calls “the secretic method,” where “you leak out enough snot, piss, and shit that people can’t be sure whether you’re serious or not.”

RWB: This relates to something I’ve always been fascinated by and that’s perception. I’m fascinated and horrified by how two people can see the same object differently, or the same color, or even how I can see my own reflection differently depending on external factors (mood, particular mirror, etc.). So, bringing this to language I become engrossed in how people manage to communicate and coexist. How do you see perception playing a role in how people relate to one another, and by extension how your characters interact on the page?

CT: As far as craft goes, I think that all stories are in the first person and that all narrators are unreliable. Even when a narrator is talking about he, she, or you, there’s still an I doing the talking, and everybody knows, when listening to an I talk, that what I says is skewed by I’s perspective.

My way of addressing this has always been to make the problem worse. I like to stay deep in my narrator’s perspective and tell it only how my narrator would, without winking at the reader, winking being, I think, disrespectful to the reader, but also maybe an act of bad faith, a denial of or (imaginary) escape from the way people actually think and feel.

I know that I already took a cheap shot at David Foster Wallace and now I’m going to look like I’m trying to get attention or like I have big brother issues, but this is what popped into my head — that Kenyon College commencement speech. He has this part where he imagines getting cut off by a Hummer and then later says it’s worth considering that maybe the guy driving that Hummer cut him off because he’s trying to get his kid to the hospital.

In fact, if you’re doing it right on earth, according to Jesus, people are going to hate you.

This sounds a little like the golden rule, but the golden rule is based in religion. Almost all the world religions, but I’m most comfortable talking about Christianity, given my background. Jesus said, essentially, treat others like you’d want them to treat you, but he doesn’t promise good results on earth. He doesn’t say, if you treat them right, they’ll treat you right, or, if you treat them right, you’ll feel consistently joyful. The joy in Christianity comes from the knowledge of grace or election or a rewarding afterlife, depending on your sect. In fact, if you’re doing it right on earth, according to Jesus, people are going to hate you. (Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.) If you take heaven out of it, there’s no reward.

But that doesn’t matter, because what Wallace describes is thinking, imagining, which makes it fiction, an act of pure language, rather than action. The thought process is life-denying; the thinker of those thoughts would rather nothing ever happen at all. Worse, it turns the golden rule into an insidious type of solipsism: attribute motives to others in a way that makes their behavior/existence palatable to you.

I guess what I’m saying is that the most honest thing I can do is let my narrator’s talk and contradict each other and themselves and hope people are willing to navigate that.

RWB: There’s a fine line between having perspective (e.g. knowing you have no idea what’s going on in the head of the guy driving the Hummer) and denying your human nature and emotions (e.g. the response of anger and frustration). We want to be, or think we ought to be, the person whose first reaction is, “oh my God, I hope everything is all right with that guy,” but for most people the authentic response is “what a jerk, I hope that guy gets pulled over.” I think they both have their place, but it’s silly to suppress one over the other. We can’t invalidate our own emotions, it’s not healthy.

Your work has always been challenging, I think the contradiction you allow for between characters is also a contradiction between the words on the page and the reader. Readers tend to naturally inhabit a book, often, depending on the POV of the story, incorporating themselves as characters. It’s a subconscious involvement. In that respect do you think of the writer-reader relationship as adversarial? Do you think there’s something to be gained from the challenging of a reader and in having faith that they can and will stick with a story?

CT: I don’t think the writer-reader relationship needs to be adversarial, but I don’t think an adversarial relationship is such a bad idea in the abstract. But I’ve never set out, in fiction, to provoke, and I think any notion that my fiction is challenging may come from different expectations of what fiction is for than level of difficulty (at least in my last few books). You mention readers imagining themselves as characters, and I guess I understand now that some, or even most, do that, but until I started getting responses to my own work, it literally never occurred to me that that might be something adults would do. As I understand it, the idea is that doing so helps you empathize with other people in the real world, but I’d make an argument that it’s probably just as likely to do the opposite — to turn you away from reading books whose characters you don’t want to empathize with. (And I think it also encourages a confusion between true empathy and relatability, which is a concept that should go away.)

In that sense, literary fiction is escapism for people who’d rather be quietly melancholy (and maybe also smugly superior) than a sorcerer.

Even if I’m wrong about that last part, writing characters for people to identify with leads to a lot of the things that I find shitty about contemporary literary writing. I would guess it’s the source of that nonsense about something or somebody having to “change,” usually through some kind of epiphany, in the course of a story or novel. That’s a trope, a convention as rigid and contrived as sword fights and car chases. In that sense, literary fiction is escapism for people who’d rather be quietly melancholy (and maybe also smugly superior) than a sorcerer.

What I try to do as a writer (and what I look for as a reader) is what a character or narrator reveals about him or herself, directly, and more importantly, indirectly. It doesn’t preclude the possibility of change, but it rejects the weird notion that everything progresses toward greater clarity, understanding, or coherence.

I mentioned earlier that my parents were ministers. They were awesome and loving people and really active in the community, but this also made them enemies. Like, somebody kidnapped our dog when I was really young. Dognapped, I guess. I was trying to tell someone about that recently, and my memory of it was hazy. All I could say was that “they” had kidnapped Maranatha, and then somebody found him in the woods, tied to a tree with barbed wire and poisoned, but still alive. The guy I was telling this too was like “who is they?” He wasn’t convinced. I actually started to doubt the memory. So the next time I saw my dad, I asked him, and the story got even weirder. I had all the details right, and that was all the details there were. We never found out who kidnapped him or why, but he survived, and after that he had dog trauma and turned nasty, when before he had been a playful, friendly guy.

I have zero interest in the novel where we track down the dognapper, and he redeems himself after breaking the inevitable cycle of violence that led him to dog abuse. There’s plenty to think about, tons of meaning, in the story we already have.

RWB: There’s a lot of focus on redemption, on finding redemption, characters needing to redeem themselves, etc. I think that’s kind of B.S. It goes hand in hand with the need for resolution in stories. I find it more interesting when the exploration is about the lack of those things, or characters who don’t give a thought to redemption. For me it feels like if those things are too apparent in a story it’s because a writer has forced them into it. With that in mind, what is the process like for you? Do you plot your work or go into a new project intending to write certain things?

CT: For me the process is different with every book. Toughlahoma started with me just messing around. I didn’t have cable when I lived in Philadelphia, so sometimes I’d go out to watch a basketball game at a bar, and one night the closed captioning looked like the transcriptionist was drunk. Somehow what I assume was a comment about the tough defense of the Oklahoma City Thunder ended up saying Toughlahoma and I thought, man, it would suck to live in Toughlahoma.

Not long after, Amelia Gray invited me to read in a series she was running then where you had to write something based on a weird prompt she gave, and the prompt she gave me was the Blue Whale of Catoosa, Oklahoma, so I wrote “Things to See in Toughlahoma.”

Then my son Wes was born and I spent a lot of time just staring at him and goofing off with him. I felt like writing, but I didn’t have the desire, much less the energy, to work on any sustained narrative, especially during the first few months, so when I got some writing time, I would just make up a new thing about Toughlahoma. I was already thinking about what old-timey philosophy called “the state of nature,” but then I had this brand new dude who was basically in the state of nature for the time being, so it seemed like the right thing to run with.

Eventually I had a bunch of vignettes, all of which made the final cut, but I didn’t want it to be just a bunch of riffs. I’m not a very intuitive writer and I wanted the book to add up to more than the sum of its parts, so I started doing math, gridding it out based on some ideas that had been in the back of my mind the whole time — from Hobbes and Locke, and also Giambattista Vico — and then figuring out what was missing and going and writing it.

Looking back over this answer, I’m not making it sound like much fun, but I think I had more fun writing it than any of my other books. The last couple of books I’d written had been, by design, a little more generous to the reader. With this one I just allowed myself to go nuts.