news

Three Muppet Conflicts & How They Were Resolved

Torture! Muppet-Haters! Hurt Feelings!

The Muppets comes out today. Last month, an article full of undisclosed sources came out in The Hollywood Reporter saying many long-time Muppets performers and crew were unhappy with it. I’m gonna see it on Friday, but a part of me wishes we could just go back to the good ol’ days… the Classic Muppet years, when everything functioned smoothly and harmoniously.

Or did it?

Drum roll, please

In 1977’s Emmet Otter’s Jug Band Christmas, there is a scene in which puppeteer Frank Oz loses his mind. Jim Henson had storyboarded a perfect bit of movie magic: a drum must roll out the door, hit some fire buckets, bounce down the steps, and then collapse in front of them, rock around on its rim until the clatter turns into a loud vibration, and then stop. In the test, they got it, “Just what Jim wanted,” in puppeteer Jerry Nelson’s words.

But reproducing that perfect percussive brr-rr-rr-smack drum roll was hard, two-hundred-thirty-three-takes hard. Oz and Nelson had to be on set for every take, had to perform in character, their “heads” “watching” the roll, following it with the puppet’s eyes, and then delivering their lines. Then they started to improvise.

In one outtake, Nelson and Oz pretend to be junkies. “Spare change?” Nelson asks the prop hand, with an almost toothless drawl, “C’mon we just need a little… y’know…” You can hear the addiction in his voice, but make no mistake, it is a cute, fuzzy, otter addicted to crack. When the next take begins, Ma and Emmet spring up like gymnasts. But the drum roll isn’t right. It was never right. “If [Jim] could see it happening in his mind’s eye and knew that it would work,” Nelson said, “he would dog it until it worked.”

Creative Director Michael K. Frith once said, “You can’t get that many artists with that much creativity in one place over an extended period of time without having your fair share of nervous breakdowns and insanity.”

But the team of performers Henson developed was truly a repertory company, a group whose job it is to interact with one another well, no matter the circumstances. “We always wanted to give Jim exactly what he was looking for,” Nelson sad. “We didn’t always know what that was, but we were willing to try until we found it.”

The Muppets Take Saturday Night

In the early days, “Jim would pound on the desk and say, ‘We are not doing children’s puppetry here!’” writer Jerry Juhl recalled. “He wanted to make puppetry for adults.”

So, in 1975, when production was starting on a new live variety show called Saturday Night Live, Henson joined up. But the rest of the SNL gang did not get along with the Muppets. They were similar in many ways — the two troupes were synergistic, rebellious, innovative — but Lorne Michaels was 32 at the time and his group were mostly unmarried, whereas Henson was already 40, already a father to five.

Head writer Michael O’Donoghue would lynch up a Big Bird doll in the writers office, and in a 1977 Playboy interview, he called them, “fucking Muppets…little hairy facecloths.” They were made from the refuse after they cleaned up after Woodstock, he said, mocking the Muppets’ idealism.

O’Donoghue refused to work with the Muppets: “I don’t write for felt,” he said. And so they were pushed off on the lowest-ranking writers. Alan Zweibel remembered: “So I went over to Jim Henson’s townhouse on like Sixty-eighth Street and I remember we’re reading the sketch, Jim Henson’s reading the pages, and he gets to a line and he says, ‘Oh, Skred wouldn’t say this.’”

Zweibel thought Henson was nuts, like Lambchop requesting her own plane ticket. “I look,” he said, “and on a table over there is this cloth thing that is folded over like laundry, and it’s Skred. ‘Oh, but he wouldn’t say this.’ Oh, sorry.” According to Zweibel, the lynched Big Bird spoke for everyone. “That’s how we all felt about the Muppets.”

Jerry Juhl said, “We went through just about every writer on the show.” Belushi, he said, “always hated the puppets.” This is not suprising. In his first interview for SNL, he told Michaels, “My television has spit on it.” Belushi hated TV in general, all TV, and Henson’s Muppets were very specifically invented for TV.

Frank Oz described those days as “tense.” Henson and the SNL writers couldn’t see eye-to-eye. In an 1982 interview, Henson said, “They were writing normal sitcom stuff, which is really boring and bland.”

Eventually, Micheals turned to a producer and said, “How do you fire the Muppets?” but it was a moot point; the Muppets left for London that year to do their own version of “adult” humor: The Muppet Show. According to Henson, they left on good terms, but as Nelson points out, “they would have pushed us out if they could have.”

The Muppets Take Saturday Morning

Jim Henson did not write the Muppets’ script — that job was Jerry Juhl’s, Henson’s first professional collaborator after his wife. Writing was collaborative, but Juhl — a cherubic-faced man with thick glasses and a constant grin — was entrusted with overseeing the scripts from 1963 on.

Juhl passed away in 2005, and in a touching LA Times obituary, Oz called him, “the person responsible really for the heart of the Muppets… He just knew the characters better than anybody else… He always saw the affection between the characters… Nobody else could do that kind of writing… He was the Muppet writer.”

But in 1984, The Muppets Take Manhattan came out and Juhl was strangely absent from the writing credits. Two writers from the Muppet Show did the first draft, and then Oz, who directed the film, rewrote it. In an AV Club interview, Oz said he wasn’t happy with the screenplay. “I was unhappy with what was done,” he said, “because it was not in the Muppets’ intended character. It was too broad, and it was not affectionate enough.”

Take Manhattan was a movie that seemed designed to appeal to a new audience: the urban and college markets. The final script introduced a new creation story: the Muppets met in college and moved to NYC. The movie also featured a scene with Muppets as babies, and a few years later, Henson would develop an animated series based on that concept, Muppet Babies.

Now, Henson had always tried to appeal to adults. SNL and The Muppet Show were deliberate attempts to show the world he was not just Sesame Street, he was also Electric Mayhem. So, when he developed Muppet Babies in 1984, Juhl objected. He wrote a long, explanatory letter to Henson outlining the reasons he did not think Muppet Babies should happen. Henson read Juhl’s concerns, gave them consideration, and did the show anyway.

Muppet Babies was not great. It was meant only for kids under seven, and the animation looked cheap. Still, it encouraged kids to read and tell stories, and it was kind of like a make-believe Rashomon, where each character argued over who gets to tell the tale. It was a show on Saturday morning that encouraged kids to build forts and colonize their imaginations. The voice work was good, original and a bit animalistic, and it won consecutive Daytime Emmys for Animated Program for its first four years.

Years later, Juhl wrote Henson another letter, this one appreciative. Henson had been right, he acknowledged — he’d expanded his audience even more with the MB franchise, and without losing the core.

Maybe Juhl fought Babies because he felt left out — it came from Manhattan, which he didn’t write, and the script for MB was written entirely by Jeffrey Scott, an animation writer who had written Superfriends and Ducktales. And maybe Oz’s current comments about Jason Segel’s The Muppets comes from the same place. Oz told the British Metro that he turned down the script because he didn’t think “they respected the characters.” The same problem he had with the original Manhattan script, and the same thing he said could only be done by Juhl. But we must remember that Hollywood gossip rags blow every hint of conflict way out of proportion — Oz politely turned down a job, he didn’t write a manifesto. Most of the paraphrases attributed to him on the Internet are malarkey.

But they have a point. Muppet writing is very hard to do. Many people mistakenly think that what children’s entertainment lacks is “edge.” When Disney acquired Pixar, they asked for “edgy” revisions in the Toy Story script. As told in The Pixar Story documentary, they almost ruined it, until Lassetter decided to ignore Disney and do it his own way. Muppet Babies lacks something, but it’s not “edge.” It’s Jerry Juhl.

Jason Segel’s The Muppets aims to capture a new audience: the 0–12 year-olds who haven’t seen a Muppet movie in theaters. Manhattan and Babies succeeded in this because they didn’t alienate the base — viewers knew the babies were separate from the Muppets. And they knew the Muppets didn’t really go to Broadway, they were just acting in someone else’s movie…

A Lesson for Disney

As Oz said of Juhl, “He was brilliant because he could be funny but not nasty.” And Henson was repeatedly called kind and sweet — adjectives that are not particularly edgy or masculine. People think adults want edge, but what they really want is wittiness. not hardness. The strength to be kind. Big Bird may be silly, but he became a goodwill diplomat to Communist China back in 1983. Sweetness may not seem ruggedly American, but in a post-industrial economy, narratives of hope are probably America’s best national export. Where would America be (competitively) without Kermit, Mickey, and Woody? Ironically America’s superman may be our most gentle.

Turning art into money (without destroying it) has never been easy, not even with Jim Henson around. So how did he do it? I’m only a mousepad historian, but from where I sit –in the devastatingly silent Cambridge Public Library — even I can see that Henson said “no” often. He said no to his tired performers, because no, the take wasn’t good enough. He said no to a creative partnership with SNL when its writers didn’t gel with his. And he said no even to the man with whom he gelled most, Jerry Juhl.

In Muppets Take Manhattan, Doctor Teeth and the Electric Mayhem sing, “You can’t take no for an answer,” but the lesson to take away from Henson’s management style is to freely and honestly give no for an answer, to listen well and then say it calmly but firmly, to protect the quality of your work. Three conflicts and three resolutions. This is a lesson for Disney as it goes forward with Muppet films — and for any creative entrepreneur — anyone interested in making (good) art pay.

***

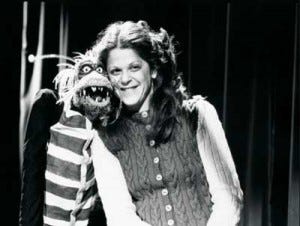

— Elizabeth Stevens is a writer, teacher, and unauthorized Muppet Historian. Her writing includes “Weekend at Kermie’s” from The Awl, “Is It Muppetational?” in Rolling Stone, “Wolf Memoirs” in Explosion-Proof, and “Saint Liz” forthcoming in Trout: Brooklyn. She writes fiction under the name Gordon Ebenezer Gourd.

Images via Muppet Wiki.