interviews

What’s Up With All These Stories About Women Having Sex with Fish?

Why the sexy merman is the monster romance for our time

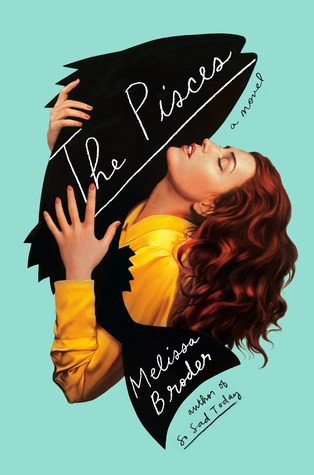

Like vampire romance before it, sea creature sex is having a moment. It’s been most notable in the buzz around Melissa Broder’s debut novel, The Pisces, which published this spring to plenty of press and favorable reviews. Much was made of the novel’s eroticism; specifically, the fact that this eroticism focused on a merman. But Broder’s debut is just a drop in what’s become a bucket. From Oscar-winning movies to recent reissues, 2018 is shaping up to be the year of women doing it with fish. It’s a strange departure from our usual romance tropes, and one that, in its strangeness, may reflect the eerie place women find themselves at this juncture in society and politics.

To be fair, human–sea creature romance isn’t an entirely new trend. The Pisces borrows from a long tradition of mermaid–human (dangerous) liaisons, with the protagonist, Lucy — a Sappho scholar — particularly attuned to the mythic heritage she finds herself embroiled in. Most human–seaperson myths and folktales reverse the genders — a besotted man and a tempting siren, a husband and his selkie wife — and the sex is generally less graphic than what Broder offers. But the romance between Lucy and her fishman follows our understanding of, and expectations for, a merperson–human love affair, right down to the potentially fatal consequences.

Then there’s this year’s Best Picture winner, The Shape of Water, which takes a more amphibious approach. The historical basis for frogman–human relationships isn’t as robust as mermaid–human ones, though a couple notable exceptions come to mind: Mrs. Caliban, the 1982 novella reissued late last year by New Directions, is a prime example. In fact, it has a strikingly similar plot to Shape: In both stories, a male sea creature is captured and tortured in the name of science. He causes some carnage in retaliation. He escapes and hides out with his human lady-love, who is inexplicably attracted to the gigantic frogman. Love blossoms. Escape plans are hatched. Things go awry.

Plot’s not all these stories have in common: there’s also the sex. In each of these examples, it’s passionate and often graphic. Which inevitably leads to a technical question: how, exactly? The Pisces gets around the confusion by starting the merman’s tail a bit lower than we’re used to. Dorothy of Mrs. Caliban never describes exactly how, or where the necessary equipment is, though in her initial description of Larry — the frogman — we get the gist: “as for the rest of the body, he was exactly like a man — a well-built large man — except that he was a dark spotted green-brown in colour and had no hair anywhere.” And one of Shape of Water’s best comedic moments involves Elisa, who is mute, pantomiming to her coworker how she and the creature were able to — you know.

Still, there’s more to these fish relationships than what happens between the sheets (or in the bathtub). The women form a deep emotional bond with their sea-lover, one that’s missing in their human relationships. In fact, we can read a second-wave feminist angle into the stories: if a woman without a man is like a fish without a bicycle, what about a woman with a fish? Constrained by society’s expectations, disappointed by the men in their lives, lonely, and depressed, the women find sexual expression and freedom by shucking conventionality and doing it with sea creatures.

The women find sexual expression and freedom by shucking conventionality and doing it with sea creatures.

And this can be fairly overt. Two of the stories — Mrs. Caliban and The Shape of Water — are set in the middle of the last century. Their protagonists are isolated by circumstances including death, disability, and infidelity, but also by midcentury American values and limitations on the roles of women. Pisces is a more contemporary story, but Lucy is nine years into her Ph.D. and only becoming more assured of its absurdity. She learns during the novel that her boyfriend of eight years has impregnated a new girlfriend just months after their breakup, and that she has lost her scholarly funding. She is notably not young. None of the women are; and they are all lonely, childless, more or less career-less, and facing ever-increasing invisibility as they age.

It’s hard to see these similarities and not interpret them as the beginning of a new trope in supernatural stories. In monster tales of old — King Kong, Dracula, The Creature From the Black Lagoon, etc. — women are victims of the creatures: kidnapped and terrified, left awaiting rescue. Any implied sexual tension has a notably rapey vibe, the better for a (human) man to swoop in, rescue the (still virginal) lady, and kill the beast. In more recent examples, the attraction between monster and woman has been mutual, though its expression notably old-fashioned. Twilight and its cohorts trade in a chivalrous notion of men struggling to control their lust — blood or otherwise — around the ladies in their midst. Traditional gendered qualities are amplified: the woman isn’t just physically smaller and weaker than the man; she is mortal, and he is not. The overly protective male so commonly found in romance novels therefore has better-than-usual justification for his extreme possessiveness. That chivalrous component remains even in more adult interpretations of the story: A show like True Blood is much more overtly sexualized — it was on HBO, after all — but still traffics in very genteel notions of romance.

But our tastes have grown up — evolved, even. Our new monster stories don’t stop shy at sex or at first blush of romance. And it’s noteworthy that the sea creatures aren’t glamorized the way vampires are; they are amphibians and fish, warts, scales, and all. Still the women love them, and care for them. And that’s another departure: these relationships have a strikingly maternal note to them. It’s a reversal of the usual protective man found in romance; now the women are the rescuers, keeping their lovers — who are, quite literally, fish out of water — safe from the dangers of a narrow-minded world. They care for their wounds, feed them, clean up after them, transport them to and fro. They find romance in these relationships, but also a sense of purpose, a feeling of being necessary that their lives had hitherto lacked. These aren’t damsels waiting for rescue — they’re women looking for ways to make their squandered agency mean something.

Now the women are the rescuers, keeping their lovers — who are, quite literally, fish out of water — safe from the dangers of a narrow-minded world.

These stories are rejections of our most common narratives, and it’s notable that the medium of that rejection is so dramatic; something has to be deeply wrong with the status quo when women choose for their companions not men, not even dapper vampires or burly werewolves, but frogs and fish, thoroughgoing rejections of masculinity. And maybe that’s why these stories resonate so well right now. Could we read — in our desire to save rather than be saved — a reflection of the current political environment, in which the fairytale that our system is impervious to demagogic influence has crumbled? (In reclaiming the girl-kisses-frog narrative, perhaps we’re picking up a new fairy tale that suits our purpose.) As long-standing norms of political conduct fall, we’re increasingly aware that no one is coming to save us. It’s this awareness that informed the Women’s Marches and the Families Belong Together marches — both attended primarily by women — turned toward fiction, a genre that has historically been the domain of women. The shadowy sadism of the governments in Shape and Mrs Caliban, seen in their treatment of foreign creatures, seems especially pertinent in light of the current administration’s fear-mongering of “animal” immigrants that — they insist — must be housed in cages. That our current administration is treating families seeking asylum in a manner reminiscent of a fictionalized government attempting to control gigantic frogmen adds another layer of horror to the already grotesque. How could Eliza, or Dorothy, or Lucy, stand idly by? How can we?

The political fight is far from over, and neither, it seems, is the trend of sexy fish: in fact, Tin House re-released Samantha Hunt’s ambiguous mermaid–human love story The Seas this week. It should make for a great beach read.