Interviews

Jeff Jackson on Writing a Novel Structured like a Rock ‘n’ Roll Record

Who killed the musicians in ‘Destroy All Monsters’?

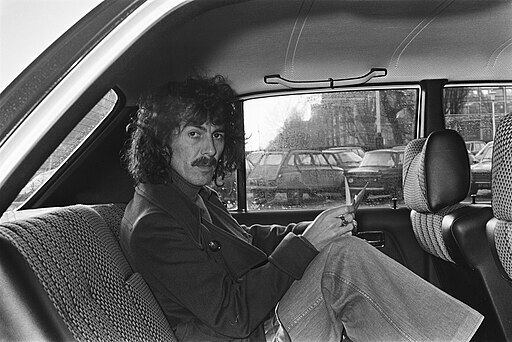

I first came across Jeff Jackson’s work through his buzzed-about first novel, Mira Corpora, which was published by indie favorite Two Dollar Radio in 2013. A hallucinatory book that is as beautiful as it is violent, I read it compulsively. Even though I finished it quickly, it was the type of book that stuck with me, filled with memorable images and a surprising tenderness. A few months later, I met Jackson at a reading. I was surprised to find out that the author behind the book was not a deranged, nihilistic weirdo, but a mild-mannered, kind man who was excited about all types of art. In 2016, the French indie press Kiddiepunk published his novella Novi Sad, a beautiful and slim volume on blue paper, that is described as a “sister book” to Mira Corpora.

Jackson’s latest, Destroy All Monsters, is his big press debut. It synthesizes all the best parts of his past works: a dreamy violence, innovative structure, thought and care to how the story is presented on the page, and a narrative that both feeds into and splinters itself.

The book takes place in the fictional town of Arcadia, an industrial wasteland complete with shuttered factories and a creepy forest that serves as a dumping ground for dead bodies and the homeless. It focuses on the city’s music scene, specifically a couple, Xenie and Shaun, who are reeling with grief from a mysterious plague of incidents that involve the massacre of different bands across the country. Like a tape, Destroy All Monsters has an A side and a B side, which can be read in either order. We discussed the process of writing the book, his choices about structure, and some of his favorite art via Gchat.

Juliet Escoria: What part of this book came to you first? Was it the idea of bands getting shot, or a certain character, or something else? With the shooting at concerts, it feels political, but also not at all.

Jeff Jackson: My notes for the book go back over 10 years. It started with the image of a band being shot on stage in a small club. At the time, it was a very surreal image. It germinated into a story about an epidemic of similar killings happening across the country. This was long before the Bataclan shooting [in Paris]. Before Sandy Hook, even. It’s been alarming how current events have caught up to the book. While it’s true that this always has been a violent country, the novel feels more realistic now than I ever intended.

While it’s true that this always has been a violent country, the novel feels more realistic now than I ever intended.

JE: So it took you a long time to go from notes to a manuscript — you said on Twitter that it took 5 years to write. I also know that the path to publication wasn’t the easiest, either, which makes sense because the book breaks a lot of “rules” about what a novel is supposed to look like. Can you talk about both the process of writing it, and the process of publication?

JJ: I had a tortured time writing my first novel Mira Corpora which went through countless drafts and radically different versions. I was determined the next one would be easier, so I worked off a rough outline for Destroy All Monsters, trying to keep the structure in view the entire time. But my grand plans collapsed under me and this novel also underwent many shifts and reorganizations. It was especially difficult to figure out how much of the epidemic I could dramatize without it short-circuiting the manuscript.

Once the book was finished, I became haunted by a vision of the novel as Side A of a cassette or vinyl single. So I started to imagine what the B Side might look like. I wanted it to be something that both fleshed out the main text and also rewrote it, offering a completely different version of events and showcasing the characters in new scenes. Several friends told me that I was crazy — that I was taking a book that was already hard to sell and making it twice as difficult.

And it was a hard book to sell. When my agent read the manuscript, she deeply disliked it. We couldn’t find any common ground on it, so we parted ways. It took quite a while to find the right person to represent the book. As often happens, the reactions from agents echoed many of the later comments from publishers — it’s well written and the story is propulsive, but the structure is too odd, it’s too dark, it’s not commercial enough. I was extremely fortunate to land with FSG and their line of paperback originals which champion adventurous fiction.

FSG acquired the book without having read Side B. Initially, I thought Side B might work as a standalone novella that could be published separately. It wasn’t until I sat with it that I realized the two parts had to be under the same cover and that together they comprised the entire project. It says a lot about FSG that they understood and embraced the Side A / Side B concept. They bought one book and found themselves with something much stranger. But also, I think, much better.

JE: Wow, that’s cool of them. I would have expected push back to that. When you say that you had to figure out how much of the shootings to dramatize, do you mean that you didn’t want this element to overtake the plot?

JJ: Yes, the killings were so charged that they tended to overwhelm everything else and set up false expectations about the rest of the story. It wasn’t until I gave them their own section on Side B that I found a way to corral their energy so they still felt very dramatic without causing readers to become overly numb to the violence. The novel uses a lot of so-called experimental forms, but they’re never there for their own sake. The unusual structure aims to make things more engaging and surprising and immersive for the reader.

I love the idea of a book that works by itself while simultaneously being in conversation with another book — and how that combination creates a third space, something that only exists in the reader’s mind.

JE: I very much felt that. The book seems mostly to be about the individual characters and their expressions of grief, with the shootings being more of a propulsive factor.

Your previous works bear some similarities with this book. In some ways, Novi Sad felt like a B-side to Mira Corpora. One thing I like about reading a writer’s larger body of work is you get to see their obsessions and the way their minds work. Why do you think you like to explore the same stories or worlds from different angles?

JJ: I don’t know exactly. I do love the idea of a book that works by itself while simultaneously being in conversation with another book — and how that combination creates a third space, something that only exists in the reader’s mind.

Maybe that comes from my admiration for Ágota Kristóf’s “Lies” trilogy (The Notebook; The Proof; The Third Lie) where each book in the sequence reimagines and rewrites the previous volume. And maybe from David Lynch, too. Destroy All Monsters was finished when Twin Peaks: The Return aired, but I felt a real kinship with how he explored parallel story worlds throughout that series.

There was already this idea of other possible realities floating through my book, these questions about whether there might be more than the surface nihilism some of the characters embrace. So maybe the impulse was less meta-narrative and more metaphysical. It felt right to blow up that question by creating a flip-side to its reality.

His Life Was Saved by Rock and Roll: an Interview with Jeff Jackson

JE: I also see a kinship to Rashoman/the telling of Jesus’ life in the Bible/the first season of True Detective. I kind of wonder why more people don’t see storytelling in this way.

Another thing I enjoyed is the different colors of the pages, and the different styles of font. One thing I like about poetry that is generally not considered with prose is the way the words look on a page, and this deviation of style in your book felt really effective and fresh for me. Did you always envision it this way, or did you mess around with the visual elements?

JJ: I’m glad that worked for you. The visual elements of the page are very important to me. It’s something I consider in early drafts and the layout becomes baked into the DNA of the book. I’ve sometimes found there’s a visual solution to a narrative problem — how the text is broken out or arranged can make something clear that wasn’t previously. In DAM, I pushed this further than I did in Mira Corpora or Novi Sad, but only because it was necessary for this particular story.

JE: So rather than being heavy-handed with explaining, you can accomplish it more subtly with a change in the way it’s presented on the page?

JJ: Exactly. These are solutions that I stumbled into out of desperation, but they’re part of a writer’s toolkit that don’t get used often enough.

JE: I’ve never really understood why publishers are reluctant to do that kind of thing, other than the practical reasons having to do with production costs.

Your novels so far are about youth on the fringes, all with a very punk rock feel. What were you like when you were Xenie and Shaun’s age?

JJ: Like them, I was obsessed with music. I was lucky to be living in New York City at a time when concerts were relatively cheap and I was constantly going to shows — seeing riot grrrl and punk bands in tiny clubs, avant garde jazz in deconsecrated synagogues, anti-folk troubadours in rundown squats, garage rock festivals in community centers, electronic and noise acts in downtown venues, etc. I wasn’t fully immersed in any one scene, but I was on the outskirts of a number of them. I was also part of a theater company, cutting up Kathy Acker texts with Buster Keaton films, making plays for people who typically hated theater. The company was run like a band and I drew on those rehearsal and performance dynamics when writing some of the musical scenes in DAM.

JE: That sounds like the dream NYC experience that doesn’t exist anymore.

One thing you post on Instagram regularly is photos with the caption Possible Novel Structure. What photo is the possible novel structure for Destroy All Monsters?

JJ: Hmmm. A cassette that’s colored violet, maybe. But that might be too literal since so many of the Possible Novel Structures invite more abstract associations. I’m curious — what would you pick?

JE: Ummmm… maybe like mirrored explosions, with some Escher-type stairs. We can put a purple tape in the middle. That’s tough.

JJ: I like that image.

7 Candidates for the Great American Rock and Roll Novel

JE: I know you read a ton of books, listen to a ton of music, and watch a ton of movies. What are some books, albums, and/or movies that really blew you away recently?

JJ: I’ve gotten behind on newer books, films, and music these days. So here are some older things I’ve been digging lately — B.S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates, a novel of pamphlets in a box you can read in any order; Carmen Laforet’s Nada, a coming-of-age novel written and set during WWII in a debauched Barcelona; Victor Segalen’s Rene Lys, a mix of autofiction and metafiction from the 1920s about life inside Peking’s Forbidden City. I’ve also been taken by a book of painter Jack Whitten’s sculptures which he created over the past 50 years but only recently started showing them.

I’m excited Criterion released Oliver Assayas’ Cold Water on Blu-Ray, one of the my all-time favorite films that’s been held up in music rights limbo for 20+ years. I recently discovered this wonderful batshit film from the 1970s called Femmes Femmes about two aging actresses who perform for each other in their Paris apartment. Two movies from earlier this year that knocked me out were Lucretia Martel’s hallucinatory Zama and Lynne Ramsay’s underappreciated You Were Never Really Here.

Musically, a lot of my listening has been guided by what I’m working on with my band Julian Calendar. It’s been a weird mishmash of Tricky’s Maxinquaye, Dog-Faced Hermans Hum of Life, The Slits Peel Sessions, and The Zombies collected singles.

But one new album that demands a shout-out is Patois Counselors’ Proper Release, an incredible record that sounds a bit like if Pere Ubu were a dance band. But more accurately, it follows Duke Ellington’s definition of great art: “It’s simply beyond category.”