Books & Culture

5 Essential Short Reads for the New Parent

The short stories that helped author Melissa Yancy through the parental fog

Soon after the birth of my first son, a friend who is a parent of two herself asked me if I felt like a different person. No, I said, in way that sounded blithe even to my own ears. For starters, I did not want to feel different. And I did not, in the way I’d heard so many others describe it — discovering some purpose, or sense of calm, or enjoying total disregard for personal hygiene or household order. I resisted those who said, you’ll see. For some, parenthood made careers less compelling; for others, the economic anxieties pushed their careers into overdrive. But I had always had my day job and my writing, so was used to a fractured, distracted existence. But did I feel like a different person? Yes, but not in the way the pregnancy and baby websites or how-to books suggested I might. I felt different in the way Rivka Galchen’s narrator in Atmospheric Disturbances — perhaps suffering from Capgras delusion — experiences his wife as “different” when he’s convinced she’s an imposter. I felt like a case study for Oliver Sacks. But not to worry. Literature had me covered. In the dream-state of the early weeks of parenthood, these five pieces proved essential companions.

“The Doppelgängers” by Helen Phillips (Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading)

“The Queen always looked profound when she pooped,” is the irresistible opening to “The Doppelgängers.” The Queen in question is a one-month old who rides regally around in her car seat, a kind of monarch — perhaps beloved and benign, but capable of wielding frightening power — and also not quite a full person, not yet deserving of a name. The story begins with a horror movie trope: the parents have moved to a new place, where the husband assures his wife that “everything will be better,” suggesting unseen troubles past. The mother is still in the hormonal blitz of birth, having not slept more than three hours in a stretch since labor. Her husband’s teeth travel down her spine like “an epidural,” and being outside the house feels otherworldly. When she does emerge, she starts to see doppelgängers — women who have the same haircut, or stroller, or dress that she does. These doppelgängers could be interpreted as a fabulist turn, or Stepford wives, or just as literal suburban reality: the mother is invited to a “Mom’s group for babies born in June,” and is “revolted and fascinated” by the concept. These scenes capture a kind of neurological disassociation, of feeling like the world you inhabit is familiar, yet askew.

I read this story when my baby was precisely one-month old, and it brilliantly enlivens what is now popularly called the fourth trimester, when a baby’s physical separateness from its mother is not yet complete. When the father tells the mother she needs to eat her food, she thinks, “The Queen is my food.”

“Choking Victim” by Alexandra Kleeman (The New Yorker)

There is the rational understanding that parenting is a frightening endeavor, and then there is the visceral experience of that terror. “Choking Victim” evokes, in a slightly oblique way, the fear of outside contagion a new infant presents, a kind of shameful Nimbyism parenthood can herald. In this case, there’s no immediate threat of disease — the choking victim is a neighbor coughing in his apartment, on the other side of the wall — but the mother fears the “formative effect” that hearing his wheeze and choke and possible death may have on her baby’s unformed, pre-verbal self. And the mother’s larger concern is about herself, her own alienation and solitude, the way she and the baby are locked in a quiet chamber of her own making. The language is delicate but chilling. “Outside the window, men walked past, berating faceless, bodiless entities on their phone.”

On a walk to clear her mind of the choking man, a wheel falls off her ugly, overpriced stroller, and to describe what happens next would be to give away too much. As in all good stories that terrify, we are left with the feeling that the real danger is not in the stranger, but in one’s own strangeness. Yet that reduces too much a story about loss of self, fear of inadequacy, fear of one’s child, one’s self, and the outside world: all manifested in action, in a perfectly inevitable escalation.

“The Midnight Zone” by Lauren Groff (The New Yorker)

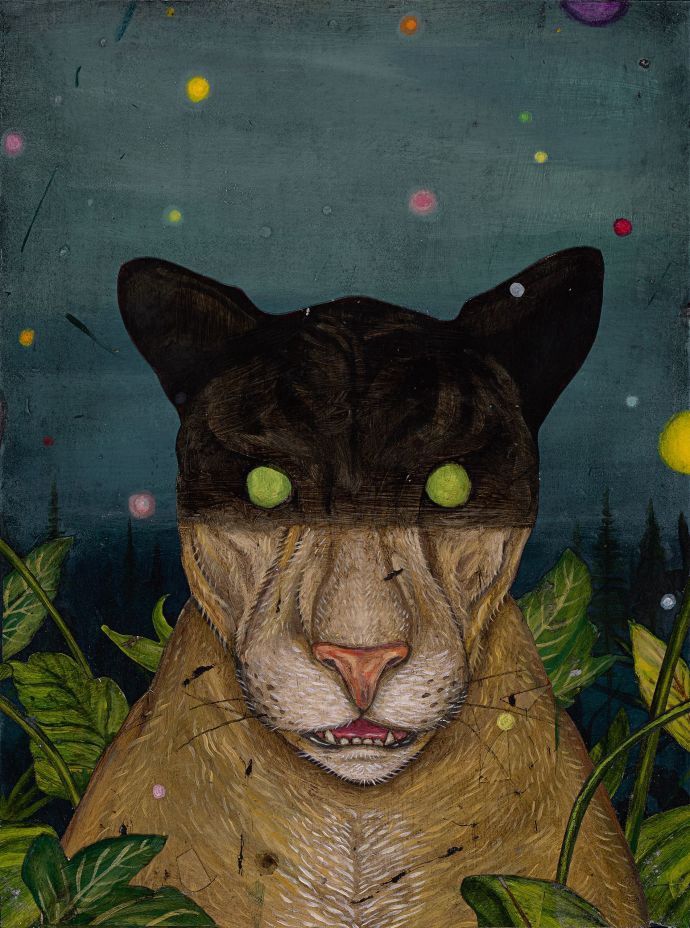

“The Midnight Zone,” too, has a horror movie premise: the mother has found herself out in the woods, alone in a cabin with her two young sons. As in “Choking Victim,” the husband has been called away for work, leaving the mother to fend for herself with limited electricity, no internet and a very weak cell signal. Again, the menace is almost lovely: “the screens at night pulsed with the tender bellies of lizards.”

Here, the sons are older, old enough to recognize they may need to care for their mother, without really knowing how to do so. “Safety was twenty miles away and there was a panther between us and there, but also possibly terrible men, sinkholes, alligators, the end of the world. There was no landline, no umbilical cord, and small boys using cell phones would easily fall off such a slick, pitched metal roof.”

The mother fears her own incompetence, while feeling consumptive love for her children, whose cheeks are “creamy as cheeses” when sleeping. “I tried to push my love for my sons into them where their bodies were touching my own skin.” Like Choking Victim,” the story ultimately asks what presents the greatest danger to a child. “I was everything we had fretted about,” the mother says.

“Story of Your Life” by Ted Chiang (Stories of Your Life and Others)

The problem with reading this story in the fog of new parenthood is that you’re in the fog of new parenthood, but this may be the time you need it most. Even if the technical details of Fermat’s principle and semasiographic writing systems are too much for the sleep-starved brain, lines that describe having a child as birthing “an animated voodoo doll of myself” will feel achingly true.

The Great Silence by Ted Chiang

I expected this story — on which the upcoming film “Arrival” is based — to be populated with alien life forms (it sort of is). I did not expect it to be a heartbreaking story about parenting, about how your babies are always your babies, forever more.

In my fog, I have wanted to explain how parenthood has changed my relationship with time, how I want it to bend both ways at once, but I have not had the language. It’s something parents try to express in exasperated clichés, and is manifested in the way people grow weepy over infants just a few months younger than their own.

The mother in the story, a linguist, finds those words, through learning an alien language that introduces her to a simultaneous mode of consciousness. Her memories, that once grew “like a column of cigarette ash” in a sequential way, now lie ahead as well as behind. In glimpses, she experiences five decades of her life — encompassing her child’s birth through her death — as a simultaneity. It’s a knowledge that’s both a blessing and curse.

This is a story that demands many re-readings, but even in a state of half-consciousness, it’s hard not to see that it’s one of the most important stories about parenthood ever written.

“10-Item Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale” by Claire Vaye Watkins (Freeman’s)

Here, in the only non-fiction piece on this list, Watkins deals more directly with the question of feeling “different,” following the birth of a baby girl. (I am reminded of Derrida’s différance, a neologism I never fully understood in college, but enjoyed saying, and which I might begin employing now, to explain parenthood.) The piece is framed through responses to a standard postpartum survey meant to evaluate the respondent’s mental state (which makes it sound much less funny than it is). In response to the questions, the narrator selects “As much as I ever did,” which the reader might interpret to mean “same same, but different.” There are standard anxieties (“in my Percocet dreams our blankets are meringue but quicksand thick, suffocation heavy, and the baby somewhere in them)” and more serious ones (“failure to thrive”) which she is reminded is not as serious as the “Nick U and pediatric oncology.” And there are the ways a mother, who may otherwise consider herself a banshee, might feel the need to playact even more explicitly now that she is a banshee with a child. When she makes a holiday grocery trip, she does not use the self-checkout lane, “the misanthrope’s favorite invention,” but forces herself to smile, to let people project onto her and the baby. I’ve heard the piece described as “about post-partum depression,” but to a new mother it read as “about parenthood,” written from within the raw, vulnerable place where terror and joy feel like the same emotion.