Reading Lists

8 Stories About How Your Family Can Mess You Up

Mandeliene Smith, author of “Rutting Season,” on the damage only your closest relatives can wreak

Every December, I gather up the holiday cards people have sent us and staple them to a long piece of ribbon draped over the kitchen window. I know paper cards are an environmental no-no, but I get an absurd amount of enjoyment out of looking at all those family pictures. They seem to me like a garland of human love and happiness; pictorial proof that everything will be all right. I try not to remember what I actually know about family: that it is there, in the smallest, most intense social unit we have, that some of our most destructive behaviors play out.

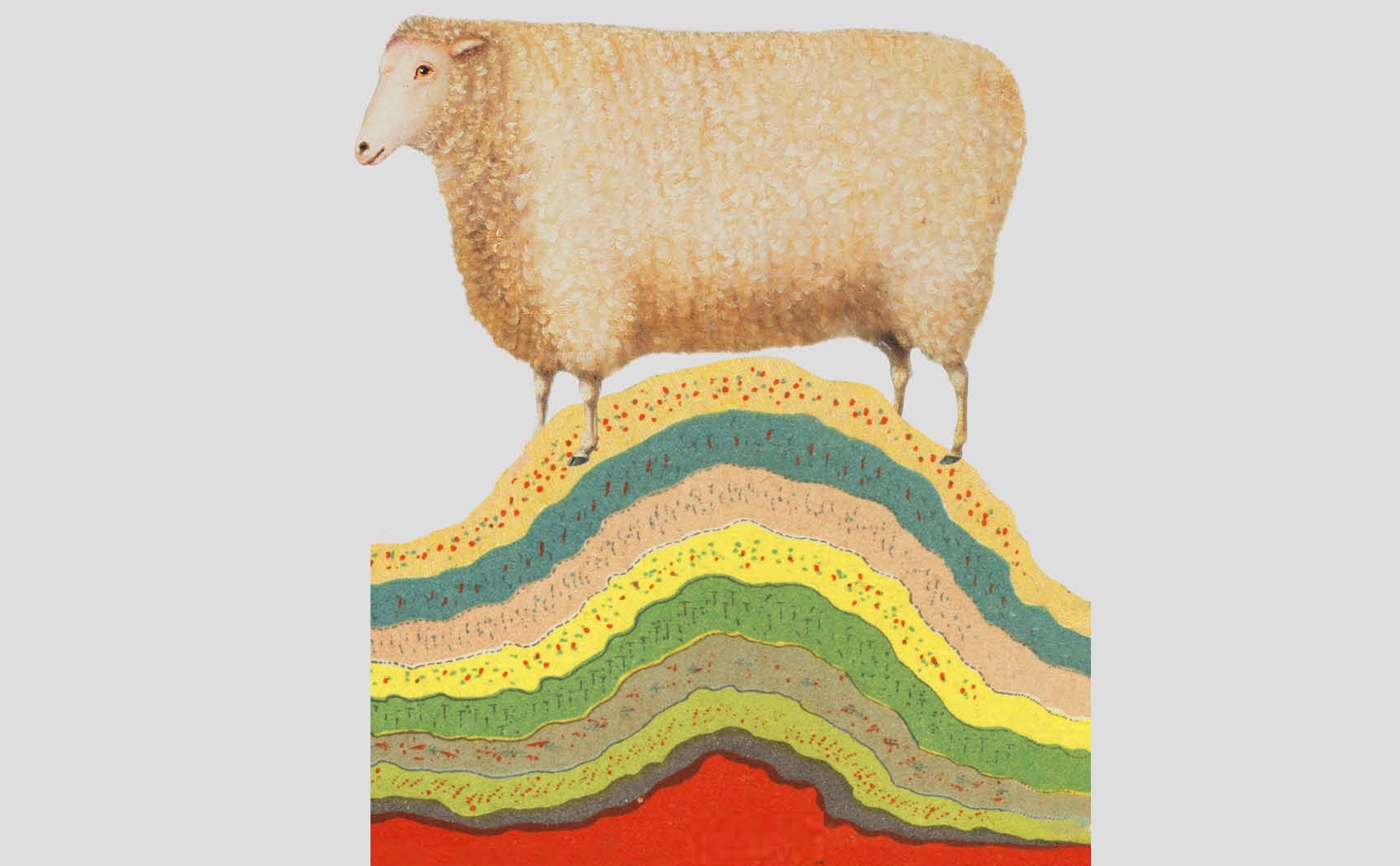

I’ve never wanted to write about my family; I prided myself on not writing about it. But now that my short story collection, Rutting Season, is finally out, I see that all the stories in it are products of that family world, or of my efforts to transcend it. Maybe this is inevitable. The reality that our parents create for us is seared into our hearts and minds: it is heaven and earth and everything between, the map by which we navigate. We grow up, of course; we escape that world, or appear to, but it never truly leaves us. It’s always there underneath, shaping our thoughts and decisions, a tectonic force made invisible by its deep familiarity.

In Elizabeth Strout’s novel, My Name is Lucy Barton, the narrator unexpectedly comes across a sculpture that captures the darkness of her childhood. But she can only feel that shock of recognition when she looks at the sculpture obliquely. If she stares straight at it, the feeling eludes her. This is the challenge, I think, of trying to show the dominion family has over us: to capture its power: you must mimic the form it takes, simultaneously visible and hidden, defied and obeyed. The following stories and novels do this, I believe, hauntingly well.

“Barn Burning” by William Faulkner

In this perfect jewel of a story, Faulkner distills his obsession with the crippling legacy of family to its essence: a boy’s bone-deep loyalty to his father and his dawning awareness that his father’s actions are unforgivably wrong. Here is the boy waiting in the country store to be questioned by the authorities about his father’s latest barn burning, a crime about which he knows his father expects him to lie:

This, the cheese which he knew he smelled and the hermetic meat which his intestines believed he smelled coming in intermittent gusts momentary and brief between the other constant one, the smell and sense just a little of fear because mostly of despair and grief, the old fierce pull of blood.

There is no escaping the brutal choice the boy must make, or the terrible cost it will exact.

My Name is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout

This extraordinary book starts out quietly with what seems a straightforward account of a mother visiting her daughter in the hospital. What could be more normal? But soon we sense an enormous emotional pressure under the surface. “She wiggled her fingers,” the narrator says of her mother, “and I knew that there was too much emotion for us.” As the visit unfolds, Strout delves below the characters’ ordinary-seeming conversation to reveal the powerful undertow of the family trauma that lives underneath. “It was not that bad,” the narrator says of her childhood. But then, in that flicker where the unseen suddenly manifests: “But there are times . . . when I am suddenly filled with the knowledge of a darkness so deep that a sound might escape my mouth.”

Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng

With breathtaking precision, Ng’s first novel chronicles the ways in which that most cherished parental hope — that one’s children will get to have what one didn’t — can do grievous harm. Sixteen-year-old Lydia Lee, the middle child in a mixed-race family, is supposed to become the doctor her mother never got to be. “She absorbed her parents’ dreams, quieting the reluctance that bubbled up within,” Ng writes. When Lydia is found drowned in a lake, an apparent suicide, her shattered parents must reckon with the devastating cost exacted by their unfulfilled hopes.

The Water Cure by Sophie Mackintosh

In this eerie, fairytale-like novel, family literally is the world. Three sisters live with their parents on what they believe to be an island, protected from the toxins of the mainland and the damage that men, they are told, cannot help but do to them. The mini-society their parents have created is bizarre and sadistic (one ritual involves what we would call waterboarding), but who else is there to ask? Even when the father disappears and three strangers bring a glimpse of an alternate perspective, the parents’ ingrained teachings are hard to escape. This deftly narrated novel sucked me so deep into its warped logic that for several days I cringed every time I tried to assert myself as a parent. All the normal parental roles — guiding, protecting, disciplining — had suddenly become suspect.

In “The Water Cure,” Toxic Masculinity Is Making Women Physically Ill

What We Owe by Golnaz Hashemzadeh Bonde

This blistering book gives us the other side of the family equation: the point of view of the parent who cannot stop hurting her child. Nahid, an Iranian refugee living in Sweden, has just learned that she has terminal cancer. The news plunges Nahid back into the layers of grief and guilt created by the events that forced her to flee Iran decades earlier. With devastating and yet somehow loving precision, Bonde shows how Nahid tries to escape her suffering by lashing out at the person she loves best. That the novel ends in a moment of grace is miraculously as believable as it is unexpected.

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson

The sheer beauty and daring of the language in this novel is reason enough to read it, but there are many other pleasures, too: vivid, lovingly-rendered characters; a sly and surprising humor; and also, I would argue, one of the best portrayals of childhood grief ever written. After their mother commits suicide in the nearby lake, sisters Ruthie and Lucille are abandoned to a rotating cast of relations. Their loss is rarely spoken of; instead, it seems to permeate everything like the smell and sound of the vast lake itself. “. . . here she was,” Ruthie says of her mother, “wherever my eyes fell, and behind my eyes, whole and in fragments, a thousand images of one gesture, never dispelled but rising always, inevitably . . .” By the end, the sense of loss Ruthie carries seems not so much her own particular inheritance as the unacknowledged state of all humankind.

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

This haunting, haunted book begins up close, in the mind of Jojo, a thirteen-year-old boy who is trying to figure out how to become a man. Worries press: Jojo’s grandmother is near death, his father is in jail, his mother cannot stay away from drugs, and he lives in a world that doesn’t value black boys like him — his own uncle was killed as a teenager in a racially tinged “accident.” And yet Jojo keeps trying, and we can’t help but love him for it. When a family trip takes Jojo back to a dark chapter in his grandfather’s past, it becomes clear that the legacy of pain he carries is not just that of his own family, but of an entire people. In spare, tender prose, Ward’s story illuminates the ways in which the invisible grip of the past shapes our lives, and asks, what do we owe the dead? And how do we pay that debt without sacrificing our own chance at living?

How Jesmyn Ward Brings Writing to Life

“Deep-Holes” by Alice Munro

Munro is a master of the hidden-in-plain-sight and one of her specialties is tracing the fault-lines within families. In this story, a geologist and his family visit a geological site where trapped water has eaten out cavernous holes in the surface rock. The oldest son falls in one of the holes; the father rescues him. All’s well that ends well — or, maybe not. It turns out, as the years go on, that the truly dangerous hole is the one created by the father’s deep disdain for his eldest son. Munro sketches this with the lightest possible touch — a disapproving look, a stray comment — and yet, when the damage finally shows, we realize we’ve seen it coming all along. The mother, on the other hand, never understands, making “Deep-Holes” a devastating portrayal of the inadvertent harm we can do to our own children.