Craft

A Master Class in Disrupting Realism and Making Magic

Marie-Helene Bertino on how to honor the rules of storytelling while breaking the rules of physics

[Ed. Note: We also invite you to watch Marie-Helene Bertino’s master class on “Disrupting Realism,” with special guests Mira Jacob, Mitchell S. Jackson, Kristiana Kahakauwila, Tracy O’Neill, and Helen Phillips. The event is free, and we encourage donations to support Electric Literature’s mission to make literature more relevant, exciting, and inclusive, and to support future programming and articles like this one.]

If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.

Carl Sagan

On Magic

WHAT IS IT?

After years spent agonizing whether it was worth money and time, I applied to an M.F.A. program for fiction writing where, during the first year, I was dismayed to find no class offerings outside the realm of realism. Those of us who wanted to stray beyond realism were not-so-subtly discouraged. One professor, upon encountering a vampire story in workshop, told the writer, “I’m not the reader for this kind of thing,” and remained silent for the rest of critique.

An enterprising sort, I wrote a petition that lobbied for a magic realism class, and after my classmates signed it, the administration agreed. A large number of students signed up across genre—fiction writers, poets, and playwrights. I was sleepless the night before class, excited to finally have answers to: What was magic realism? How could I write stories like Aimee Bender, who evoked emotion while being funny?

I assumed the administration would hire the utmost expert on magic and fiction. Gabriel García Marquez himself, if he were available. (Now that I’ve been teaching on the under-and-over graduate level for over a decade, I laugh at my naivete.) During their introduction, the assigned professor admitted that they did not know much about magic realism. They’d looked it up online and couldn’t find many good resources.

Lacking academic guidance and aware of the stigma—a barely imperceptible curdling of expression when certain authors were mentioned—I set about figuring it out myself.

American magic realism was often dominated by the affluent, usually white men and women, so I ventured outside America, to Japan, for example, where I met writers like Yōko Ogawa and Taeko Kōno on the page, and to film, where filmmakers like Agnès Varda and Federico Fellini didn’t seem to struggle under the stigma against breaking realism’s rules.

The working definitions and methods contained herein are imperfect. They are, however, mine. They are tools I’ve invented to classify work that falls within the realm of what I consider the uncanny. They are intended to provide ways to build the uncanny into a new practice or bolster an existing one.

PICASSO WAS TERRIBLE TO WOMEN

Once upon a time a man reproached Pablo Picasso for painting surrealistically.

“Why can’t you paint more realistically?” the man said.

Picasso said, “Show me what you mean by realistic.”

The man pulled a photograph of his wife out of his wallet. Picasso looked at it and said, “So your wife is three inches tall, has no hands or legs and is black and white?”

As soon as we make a mark on a page, we seek to control space and time. Perhaps before, when we go to our preferred writing mechanism, the computer, the notebook, or even before, at the inciting moment when our imagination begins to morph a lived experience into a narrative, we are already manipulating, editing, changing. However, controlling time is impossible and, perhaps most excitedly, doomed to fail.

There is no such thing as accurately representing reality on the page. What a relief!

These tools and methods are meant for writers who stray outside realism, which is to say, all writers.

THIS ESSAY WILL NOT

This essay will not offer definitive terms of categorization. It will not enter the debate on what is and what is not magic realism, the surreal, the uncanny, fabulism, speculative fiction, sci-fi, fantasy, etc… Whatever time I’ve spent debating what one of these genres is or isn’t, has felt antithetical to the inventive and expansive nature of that genre. It has also taken me away from my work trying to map new terrain within it.

My working definition, when I explain my writing to myself, is that at some point in one of my stories or novels, a law of physics is broken. That could mean anywhere from a singular, discreet instance to the story’s entire fabric (more on that later). This essay will remain focused from a craft perspective on how and why to effectively implement elements that break the laws of physics on the page.

Though my work has been described as “magical realism” by others, I tend to use the terms surreal and uncanny.

If you are a teacher or editor or reviewer or arbiter of writing—if you are in any way in charge of a process of merit and distinction—that includes a piece of surrealist work, I hope you will use this essay to help you more effectively meet, evaluate, and reward the piece where it is.

WHY WE BREAK THE LAWS OF PHYSICS

Because we want to imagine ourselves out of our circumstances. Because we’ve been handed these stories by our ancestors and it is part of our culture. Because we are a member of a culture or class for whom it is radical to imagine a future. Addressing the lack of Indigenous and characters of color in science fiction literature on NPR, N.K. Jemisin said, “They were set in these so-called futuristic settings where we were the myth.” Perhaps we want to break the laws of physics because it’s fun, because we want to reach a particular emotional resonance unable to be accessed through conventional methods. Because we do not think using the supernatural elements is out of the ordinary. Because the supernatural is our ordinary and to write realism would be, for us, stranger. Perhaps we venture outside realism because to express our understanding of life, because removing the middleman of simile and making the figurative real feels more honest.

Once, I became so happy so fast that I balled my hands into fists and was certain I was about to take flight.

Why then can’t I write in a story: She flew?

WHY BREAK THE LAWS: On humor, a personal story

Yesterday, I heard a particular laugh from a man in his 60s or 70s that meant he was surprised that someone like me (small, a woman) had said something he considered to be funny. I’ve heard this laugh my whole life because my whole life I’ve

- a. made a lot of jokes

- b. have looked this way

Maybe it shouldn’t, but it always pleases me to hear this laugh. And annoys me. Equal parts pleased and annoyed.

Though they are tall and muscular, my brothers also make a lot of jokes. We do this because we had an abusive father.

Among his other faults, my father was a literalist who, like many literalists, described his humor as “dry.” Also like many literalists, he considered himself to be funny and wasn’t.

A five-year old is unlikely to be approved for a home mortgage. Since we couldn’t move out or protect ourselves against my father, my brothers and I did the only thing available to us, we made light of him. This allowed us to stave off the unseen injuries of trauma long enough to reach the next, hopefully more peaceful moment.

Here is a line from “Free Ham,” one of my first published stories, that still makes me smile:

“The next time I see you,” my father says. “I am going to back over you with my car.”

“You’re such a bad driver,” I say. “You’d probably miss.”

Humor also changed my father from a real-life man into a subject. Though it would not shield against depression and PTSD, this seemingly small but crucial shift created a buffer, enabling me to distance myself from what was happening to me. People who have experienced trauma describe this disorientation as akin to a dream state.

As an adult, I no longer need humor to physically survive. Yet, its origins remain in survival.

As I got older, the sense of humor that had its origin in survival procured me access to certain clubs that would have otherwise never accepted my poor, weird, fucked up, ethnic ass. Friend groups, party conversations, writing industries. Noticing how this ability acted as social lubricant, I cultivated it, studying comedians, memorizing whole monologues. The literary canon is relatively humorless. When I abandoned poetry (and it me) and began to write fiction in my 20s, there was a conscious moment in which I had to grant myself permission to be funny.

I’ve never wanted to write about my personal life. I am writing about it now because I saw this video of Patrick Stewart hugging a domestic abuse survivor and realized there are people in abusive situations who might benefit from a similar kind of permission.

As an adult, I no longer need humor to physically survive. Yet, its origins remain in survival.

I use supernatural elements in my stories and novels because they most adequately render what I notice about memory, trauma, disability, class, ongoingness, and what we mean to each other. Many of my stories are in present tense with present tense flashbacks because of what I’ve noticed about life and memory, that to remember something feels like reliving it.

Humor and magic work similarly. They allow us to escape our circumstances, if only for the length of a joke, a transmogrification. When you undervalue either, you are privileging easy and direct expression and failing to understand that the construction of a joke or a supernatural element is an act of survival by the oppressed.

Illustrations by Leanne Renee

JUDGES WITH ONLY ONE RULER

Those of you who’ve watched a dog show will be familiar with the Best in Show round, during which a judge stands in the center of a ring, surrounded by different breeds of dogs and their sensibly shoed owners. One by one, the judge asks each dog to run around before kneeling or, in the case of smaller dogs, lifting the dog onto a podium for closer inspection.

Dog show judges are required to be up to date on the specifications and qualities of every breed. How the slope of a Shih Tzu’s nose should slant, or how pointy a Pointer’s pointer should be. At any given time, the judge maintains a mental card catalogue of the perimeters of, as of this writing, 190 dog breeds.

It is important to note that even in the Best of Breed rounds the judge does not evaluate the dogs against one another, but by how good they are at being themselves. In the Best of Show round, before judging a new dog, we can imagine the judge shifting their mental yardstick in order to measure the dog in front of them with the correct, breed-specific ruler.

Imagine instead if the judge memorized only the specifications of the Standard Poodle. When judging a Yorkshire terrier, they’d declare, this dog is too short! It doesn’t have coarse, curly hair! It doesn’t seem at all like a dog I’d want in my male pattern baldness medication commercial!

I read many reviews and hear many conversations and have sat in on many editorial meetings judged by people who prefer their fiction stay in the realm of what is “realistic.” When a gatekeeper faults writing for containing rule-breaking elements or for being written by someone who does not look like what they are used to, the gatekeeper is saying: You fail because you are not a Standard Poodle.

But, it is they who fail. Because they only know one ruler, one method of classification.

CLASSIFYING MAGIC

While I’m not interested in classifying pieces from a marketing perspective, I am deeply invested in identifying how they work as a guide to writing them. Because I was occasionally taught by teachers who seemed to have only one method of classification, I had to develop my own. Over the course of many years I developed this scale.

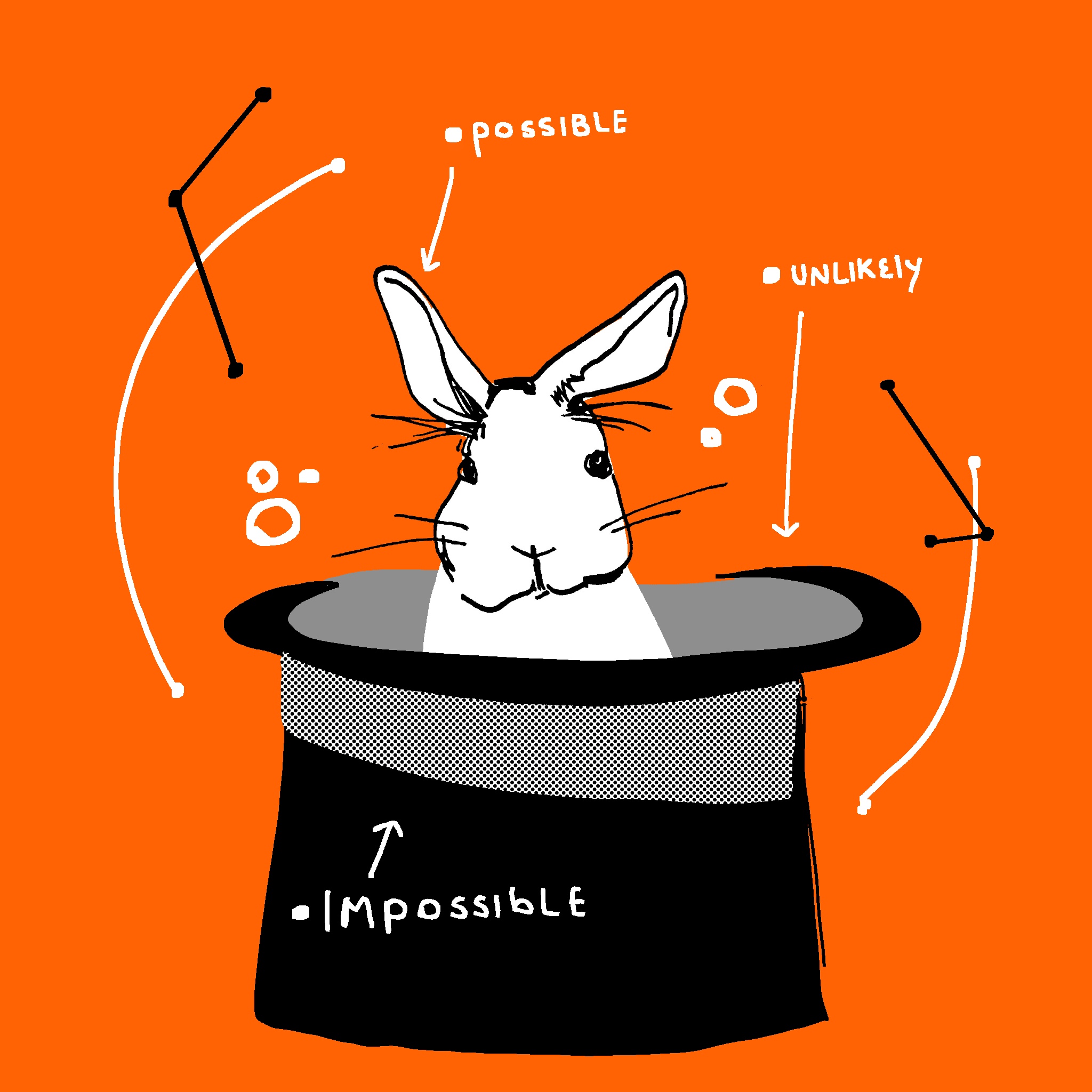

Imagine #1 is a story in which every single thing is possible (as much as it can be, remembering Picasso). And, #10 is a story where almost all if not 100% of the world is invented. #1 could be an Edward P. Jones novel, perhaps, and #10 might be “Blood Child” from Octavia Butler.

In the terrain around #5, things aren’t completely possible or completely impossible, they are highly unlikely. I consider the realm between numbers 5 and 10 to be The Uncanny.

This is where the work of some of my favorite writers resides. Yōko Ogawa, Ramona Ausubel, Toni Morrison, Lydia Davis, Joy Williams. In an Amy Hempel or Raymond Carver story, nothing technically impossible happens yet the ratio of known to the unknowing is so tilted toward the right that a feeling of unease grows. This unease is created by highly unlikely scenarios, omitting information other writers would deem necessary, and—especially in Hempel’s case—beginning stories in the middle of a thrust of thought or conversation. I teach them as surrealists.

Using this scale, however, we are still judging uncanny work in relation to the so-called “real.” The implication is still: This is or is not like the Standard Poodle. The time we spend weighing work against realism could be spent understanding and digging deeper into the possibilities of the uncanny.

So, I mentally lop off numbers #1 to #4.99, saying goodbye to realist works as reference, and elongate the scale.

Instead of referencing work by how it is or is not like realism, thereby still making realism the focal point, we make the entire scale uncanny. We are then able to dig deeper into and discover new things about that terrain without the unhelpful tether to the so-called real.

If I’ve just written a story that hovers around 10, I tend to want to write a 6 or 7 next. If I’m struggling to see a piece clearly in revision, I’ll ask myself where it seems to want to lie on the scale. This helps me revise toward where the piece seems to be going, instead of where I’m normally trying to inelegantly push it.

HOW DO YOU SOLVE A PROBLEM LIKE MARIA?

A note about the rigidity of the scale. As it is meant to “classify” the unclassifiable, it should be noted that the term “classify” and “scale” is being used loosely, in order to make the idea of it visible and accessible to as many writers as possible. The scale points are deliberately vague and up for interpretation to allow for each writer to populate them with their own understanding.

Can you accurately classify the surreal?

How do you hold a moonbeam in your hand?

Illustrations by Leanne Renee

MESSING WITH TIME

As I wrote earlier, whenever we make a mark on a page, we seek to control time. Every decision regarding tense, person, and the unsexy but totally revelatory ordering of scenes unfurls a list of pros and cons. Present tense charges a scene with immediacy while sacrificing a bit of perspective. Past tense offers a buffering distance that can assist or hinder resonance. I ask my students (and myself) to begin thinking about what their personal relationship with tense and person will be.

Reverse chronology, when a story moves backwards in time, can be valuable for, among other reasons, supporting characters who wish to recede from a painful event. In Lorrie Moore’s “How to Talk to Your Mother,” a woman retreats year by year away from her mother’s death, literally reverting to childhood. Grief can be encountered meaningfully in this structure.

A time loop story presents an ongoing condition of entrapment. Time is repeated in a whole chunk (one day over and over), or in segments, or one discrete character or idea is repeated. The Invention of Morel, a novel that represents one of the most inventive examples, the idea of the loop is upended when an island of partygoers turns out to be a recorded, endless projection. Loop stories bring this con: even the repetition of a wild day becomes a pattern that can bore the reader. I find it necessary to upend the expectation of the repeated element after one revolution.

Time can diminish and expand based on the needs of the character. In Tobias Wolff’s famous short story “Bullet in the Brain,” a moment of death is prolonged for four pages. Time may be condensed, a family history being truncated to three sentences. Present, past, future, implied, summarized, “real,” and imagined time can aid in rendering the human experience.

The measure of time my students have most trouble with is collapsed time—when all time is present. Virginia Woolf uses collapsed time in her page-long sentences, and my novel Parakeet contains at least three that do the same. These effects work best when meaningfully connected to philosophical reasoning. Parakeet chronicles a wedding week, in which, during several uncanny episodes, The Bride falls to metaphysical pieces. When she is experiencing trauma, her understanding of memory is overwrought by the simultaneous and her senses compartmentalize. Collapsed time blooms in this climate. In a chapter titled, “A Wedding is an Internet Where Everyone Sees Themselves,” a solitary moth flies through the wedding limo, essentially halting “real” time and connecting her past, present, and future selves. The moth is a needle, stitching together all-time.

Punctuation marks are the sous chefs of time. Periods halt it, em dashes intrude and infuse the main thought with drama, commas seek to order it, semi-colons dice it, etc… Parenthetical expressions and footnotes can contain entire narrative strands. With practice, if you assign music terms to punctuation, rests to page breaks, then with a cursory scan of a page of prose, you can hear a scene before you read it.

MESSING WITH SPACE/STRUCTURE

Structure is a container that supports meaning, but structure can be shaped like anything. In 2018 at Institute for American Indian Arts, the writer Kristiana Kahakauwila gave a craft talk called “Clocks, Questions, & Canoes: The Vessel as Story Structure.” In it she described how a story’s meaning can order itself into vessels as varied as voyaging canoes, flower petals, and hermit crabs.

Time also moves within a page’s white space. Page breaks, chapter endings, blank pages do not have to impede narrative movement. Vignettes and flash fiction seek to crystallize time while shuttling the reader back and forth through time in the negative space that connects them. From one section to another, ten minutes may have passed, or a century, or no time at all. While revising, I go through, for example, the implied time between each chapter’s ending and the beginning of the next and list the amounts. Sometimes when a book feels uneven it is because I’m asking the reader to shuttle too far into space too quickly, too many times. Page space is a time machine.

MESSING WITH RELATIVITY: A few writing prompts

- Give an impossible person a possible job or task

In the movie A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, against the charged setting of teenagerdom, a female vampire balances twin desires: blood and connection to an almost-equally troubled boy.

- Give an impossible person an unlikely job or task

In Ramona Ausubel’s short story, “You Can Now Find Love,” Cyclops writes a personals ad, riffing and deepening what we know about that mythical creature and the vulnerabilities of dating.

- Give an impossible person an impossible job or task (all Greek myth)

- Give a possible/unlikely person a possible job or task

In Aimee Bender’s short story, “Loser,” a boy with a supernatural knack for finding lost items must find a young boy who’s been kidnapped. Bender meaningfully engineers the character’s supernatural ability to play against his big desire—by the end the reader realizes that the thing he’s lost he will never be able to find.

- Give a possible/unlikely person an unlikely job or task (every Yōko Ogawa story)

In Yōko Ogawa’s “Sewing for the Heart,” a seamstress is commissioned by a cabaret singer who was born with her heart on the outside of her chest to sew a leather holding case to protect this vital organ. As is true in most Ogawa stories, it does not go as planned.

- Give a possible/unlikely person an impossible job or task

In Manuel Gonzales’s short story, “The Miniature Wife,” a man accidentally shrinks his wife to Smurf size. Though he and his wife are both realistic, their predicament is surreal, and through it Gonzales is able to elucidate darker truths about marriage and partnership.

Illustrations by Leanne Renee

GUIDEBOOK TO BREAKING THE LAWS

There is normally a moment in revision when I realize I haven’t fully committed to the supernatural element. There is a hedging on my part, an unwillingness to believe in my concept. I’ve found that the supernatural element works best in a story when it is meaningfully connected to the interiority of one of my characters. In this way, I implicate it, make it integral.

In revision I check my work by imagining the removal of the supernatural element. If the story can function without it, I have more work to do.

Building legend

Building out the supernatural element means placing it into a society and writing out the real-life entanglements that would occur. The examples are limitless; stories, rituals, news reports, histories, museums…These entanglements could stay on a local level or could get as big as the universe. In the aforementioned Aimee Bender’s story, “Loser” the boy who can find things becomes infamous in his neighborhood, where naysayers crop up alongside believers. Language and lore grow around his ability.

Who are the protectors and believers of your supernatural element? Who are the detractors? Does the supernatural element have unintended consequences that become their own systems with their own hierarchies?

A common villain in supernatural stories is society in the form of a mob. Vampires, cunning women, troubled seamstresses, and more, have found themselves violently pursued by a community that seeks to tame them. Perhaps this echoes the experience of the unconventional person growing up in suburbia.

In the Director’s Commentary of the movie Edward Scissorhands, director Tim Burton says the truly macabre scenes are the ones set around so-called normal barbeques in suburbia. These scenes were based on his Santa Monica childhood, and he goes on to say he can’t imagine anything more horrifying than these kinds of parties. In direct relation to the suburb’s varying fear levels, Edward’s scissor hands are perceived as deformity, then ability, then, ultimately, threat. He goes from feared to loved to feared again to attacked and destroyed. It is no wonder that supernatural stories like Edward Scissorhands have been championed by disability advocates for its inclusive themes.

The mob holds the discerning, self-congratulatory mandate created by fearful Group. It can take the shape of Missoula, Montana, a bachelorette weekend, one ruthless editor. Even when classically appearing as the innocuous suburb, the mob represents the status quo that characters like Edward’s “deformities” violate.

Engineering a useful tone

Gabriel García Márquez famously had trouble with the tone of One Hundred Years of Solitude. The published novel—a terrain in which ghosts are commonplace— is driven by a nonplussed narration, but in early drafts the arrival of each ghost was accompanied by narrative fanfare. The supernatural was reading outlandish and disruptive. Garcia Marquez said the tonal disagreement was solved when he remembered that his grandparents considered ghostly visitations as quotidian events, and the novel acquired its iconic matter-of-factness.

Labels are slapped on work that breaks the laws of physics, but for many of us, ghosts are not an event. Toni Morrison held similar sentiments regarding any “supernatural” elements found in her work. I think of this when reading Louise Erdrich’s first novel Love Medicine, where the dead seem to walk among the living with no fuss. Running beneath these ideas: the writer may not believe any of this is out of the ordinary.

Know what you’re in conversation with

Even supernatural elements bring reader expectations. It’s wise to know how everyone else has written about some of the more common ones so you can upend archetypes and patterns. For example, vampires have been done to death. (Pause for laughter.) Depending on the source, their mythology includes aversion to light (in some cultures the vampire turns to ash), toxic masculinity, death only by a stake through the heart, needing human blood to live. In the aforementioned film, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, the vampire lives in a depressed, crime-filled town in Iran. When the archetypes of the famous night dweller are seen through the new lens of a young woman feeling isolated in her teen years, new terrain is discovered in an old subject.

What are the common tropes of haunted houses, ghosts, werewolves, witches? I don’t believe there is anything that can’t be written in a new way.

Writing across experience

As in realistic writing, writers of the surreal must be respectful of existing systems of oppression. Certain myths and mythic creatures belong to closed cultures. For example, the rougarou is an Indigenous figure akin to the werewolf. Non-native writers wishing to participate in rendering it in story are writing into someone else’s lived experience and ritual. Afro-surrealism is an artistic form that Black artists use as an expression of survival and beauty. By definition, it cannot be created by non-Black artists.

When considering writing across experience, the first question must be, Why must I do this? In which direction is the power dynamic going? If I were to write across my own experience, would I be participating in these systems of oppression?

Engineer a character who would most benefit (or suffer from) the Supernatural Constraint/ Engineer a Supernatural Constraint that would most benefit or test your character

Addiction, like time loops, involves repeating the same behavior. I notice that many protagonists in time loop stories have self-defeating, narcissistic, or addictive natures. A useful narrator in a time loop story can be one who is ignoring something the structure is forcing them to relive.

To write a story in reverse chronological time, I ask myself what kind of character would be most opportunistically affected by that scenario? A grieving one? Perhaps one who wishes to leave their past behind? Perhaps one who desperately wants to forget a mistake? Reverse chronology can be a useful structure if a character wishes to distance themselves from an event.

Meaningfully dispense information

Many uncanny texts reveal themselves as uncanny in their first lines. Or, they subtly signal the questionable nature of reality within the first pages. This might be because readers aren’t always delighted (see: my Goodreads reviews (I won’t)) when the realistic story they thought they were reading suddenly contains a flatulent unicorn. An unseen contract to tell the “truth” feels violated. If withholding the supernatural element, it may be beneficial to ask, why? Does it help your story or is it to manufacture suspense that might be built more effectively another way?

BREAKING THE LAWS OF PHYSICS WITHOUT BREAKING THE LAWS OF FICTION, WHICH ARE NON-NEGOTIABLE

The writer of the surreal is doubly charged to engineer their story to work on the literal and metaphorical levels, while reckoning with craft. Surrealism gets a bad reputation perhaps because readers worry that wild premise will flatten character and emotional resonance. The surrealist writer is still charged with developing complex, contoured characters who contain vulnerabilities and contradictions. Those characters are still charged with having big desires that force them to make decisions that put them in the path of other characters with their own desires. The line level is charged with being exact and surprising even when describing a supernatural character. Like many things, that’s the good and bad news.

OF MAGIC DOORS THERE IS THIS/ PORTALS

“…you do not see them even as you are passing through.” Charles Baxter refers to watershed moments in fiction as “one-way gates.” After a character passes through, they cannot return to the idea of themselves they held before. A kiss, a conversation, the mind of your brother-in-law, a wardrobe. Portal, portal, portal, portal. Anything can be a portal if a character or situation has changed after passing through it. When you adjust your way of thinking, every work of realism contains a portal.

THIS ESSAY WILL

Growing up, I received particular insight into the arbitrary nature of rules. My mother worked so many hours a week to support my brothers and me that she instilled mandates to take her physical place. I was not allowed to visit friend’s homes or go on sleepovers or overnight trips. It was her way to keep me safe. Many childhood structures seemed to impose maximum judgment while offering no substantive support or fun: The Roman Catholic Church, the suburbs, popular friend groups. Now, as an adult, I sometimes notice the same limiting in structures professing to be unconventional.

Sometimes rules originate from a desire to lessen the existential ache of the blank page. We fear what may happen if we are let loose in unhindered space. Rules provide helpful limits against which to creatively flourish, while ignoring the inevitability of death. However, fear cannot change the inevitable, it only hinders joy.

I wouldn’t allow my mother’s fear to prevent me from participating in life, so I began sneaking out of my bedroom window to meet up with boyfriends and friends who drove me out of the city. The particular combination of the radio and country roads at night was the most joy I’d known. As we drove past night meadows of sweetly feeding deer, each one lifted silently into the air.