Lit Mags

A Story About the Threat of Teenage Sexuality

“Nuclear Heartland” by Catherine Cooper

AN INTRODUCTION BY MICHAEL REDHILL

Catherine Cooper’s short story “Nuclear Heartland” presents all of the author’s strengths in one place. Minutely observed, dark, daring, and funny, it’s a gem of storytelling that shows how much world you can pack into four thousand words.

Ange lives with her mother in Souris, Manitoba, and hasn’t seen her father in over a year, but here he is to take her on an overnight “environmental awareness” father/daughter road trip. He’s going to show her where the nukes are buried in North Dakota — they’re in farmers’ fields across the state, in secret places with nicknames like Contaminated Evermore. He’s charged up; she’s preoccupied.

It’s not clear to the reader what has triggered the father’s bout of paternal bonding after a year’s absence, but his interest in Ange seems to be in earnest. However, he can’t know — while he’s quizzing her on nuclear fallout — that all she can think about is the motel room where they’re supposed to spend the night. At fourteen, she’s ashamed of her overdeveloped body and she’s not sure there will be two beds at the motel. (To travel with him, she’s wedged herself into a Rube-Golbergian bra that barely supports her and is held together by safety pins.)

Catherine Cooper is a fearless writer. She goes into crannies like she’s stalking darkness itself. From the first lines of the story, she establishes a mood of dread that seeps into the sentences like smoke. Ange goes with her father because she feels sorry for him, but she regrets it right away, and the reader begins to worry that Ange is not safe with him. But is she in any actual danger, or has the threat of becoming sexually mature simply paralyzed her with anxiety?

Cooper goes into crannies like she’s stalking darkness itself.

She’s so preoccupied by the overnight plans that she’s not paying attention when they reach Holy Terror, their destination. Her father points out the huge concrete slab over the intercontinental ballistic missile buried beneath it, which points at Russia. It’s no coincidence that Cooper sets the climax of this uncomfortable journey in a location with a concealed forty-ton phallic symbol.

Cooper’s writing is totally stripped of fat, and her sentences are packed with images and insight. “The corn hissed like a field of punctured tires,” she writes, as father and daughter arrive at Holy Terror. Remembering her mother’s grief when her father left them, and how she reacted to that grief, Ange recalls: “It tugged like a fish hook in her, and she went toward it not out of love but out of fear of being ripped apart.”

“Nuclear Heartland” ends at the dread motel, and the story is propelled to its alarming, but quietly renewing, denouement. Cooper’s courage as a writer is in her desire to look at her characters and their relationships unflinchingly. In this story, she offers us a restrained and artful portrait of two strangers related by blood.

Michael Redhill

Author of Consolation

A Story About the Threat of Teenage Sexuality

Catherine Cooper

Share article

“Nuclear Heartland”

by Catherine Cooper

Ange stared at her father’s hairy hands on the steering wheel. How gross, she thought. He’s like an ape. “Next is Holy Terror,” he said. “Read me the instructions.”

She opened the guidebook and searched for the name. Her finger traced the pages that were most heavily marked with his messy handwriting, past Contaminated Forevermore and Prairie Primeval until she found it, between To Be or Not to Be and Whamo Grano Blamo.

“From the railroad tracks at Greene, go north two dot five miles on State Highway 28,” she read. “Then right two dot seven miles.”

“Point seven,” he said. “The dot means point.”

“Missile is on the left.”

Putting down the book, she turned uncomfortably in her seat belt and a spear of underwire bit into her side as she looked out the back window at the dust rising between the car and the barbed-wire fence surrounding Justice Stops Here. She wished she had the nerve to ask him, so she could think about something else. Maybe she could make a joke about it, like it was no big deal. Or she could just say it directly, but if she was going to do that, she should have done it when he mentioned the Motel, which was hours ago. If she said something now, it would seem like that was all she’d thought about in the meantime.

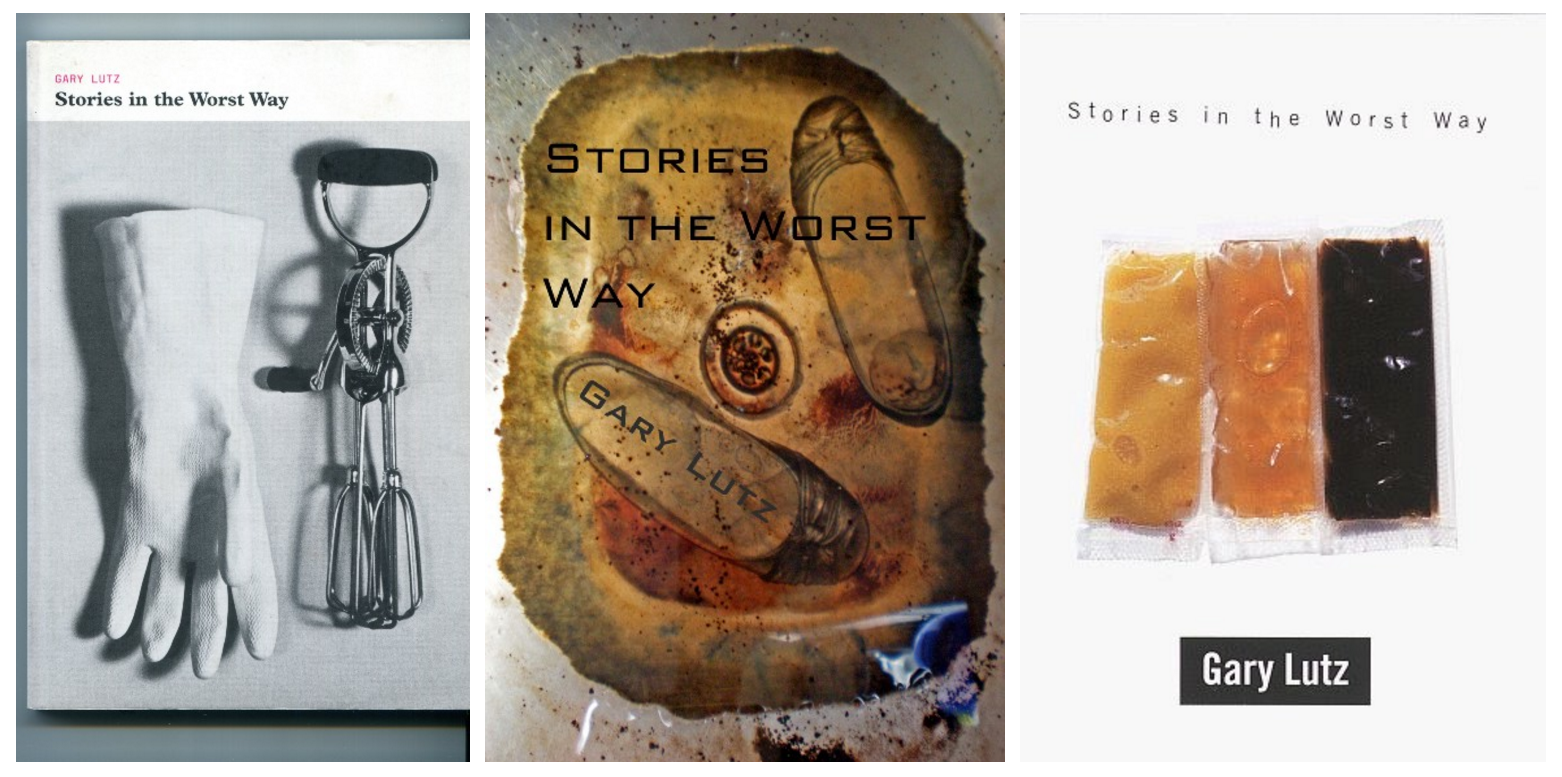

Nuclear Heartland (Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading Book 276)

“Are these the railroad tracks?” he said, suddenly frantic. “How are you supposed to know if this is Greene? There’s nothing here!” As usual, she didn’t know the answer, but she turned to look out the front windshield to show solidarity with his latest navigational conundrum.

The trip had begun that morning, when he picked her up from her mother’s house in Souris, Manitoba. She hadn’t slept much because her breasts were throbbing and she couldn’t find a comfortable position on her side or back. She was used to sleeping on her stomach, her hands folded under her like a little angel, but there was no room for her arms any more.

She’d had to rush through breakfast because she knew it would take at least half an hour to rig up the beige granny bra from Eaton’s that she had converted into a kind of binding device. First she sucked in and pulled the bra over her head and shoulders. Next she leaned forward and slowly stretched the material over her breasts, one at a time. Then she had to disperse each breast within the bra, stuffing the sides under her armpits. After that, there was a whole system of fastening and adjusting involving an arsenal of safety pins and elastic bands. In the end, she’d settled for a slightly lopsided, smooshed-to-one-side look in exchange for a setup that was bearably painful and rarely stabbed her or came undone.

Meanwhile, her mother had spent the morning carefully arranging her hair and makeup to look like she’d rolled out of bed even-skinned and gently tousled, and the two of them had fought over the bathroom like a pair of teenagers. Ange knew her mother’s preparations meant she was planning to come outside when he arrived. It drove her crazy the way her mother performed for men. With some, she played at helplessness, saying things like, “It’s so good you were here. I have no idea about these things.” With others, usually the ones Ange liked best, she was cold and arrogant for no reason. With Ange’s father, it was always the independent woman routine, which left Ange torn between whatever loyalty she still felt for her mother and her desire to distance herself from the embarrassing display.

Despite the various acts her mother put on for men, Ange knew that she hated them all equally. “They’re all out to get you,” she told Ange, who had been shamed into wearing baggy clothes and keeping her T-shirt on in the pool since she was ten. “They only want you for your body,” her mother said, but the way Ange saw it, at fourteen years old, her body was completely trashed anyway. Her breasts were rippled with bruise-colored stretch marks, her ribs were deformed by the constant rubbing and digging of underwire, her shoulders were rutted with grooves from her bra straps, and her spine was probably growing crooked because when she stood up straight the other kids said she was flaunting her boobs.

It had been more than a year since Ange had seen her father. When he had called to suggest the trip, he’d talked to her mother for at least five minutes before asking for Ange, who was so preoccupied with trying to figure out why he was talking to her mother that she was defenseless when he asked if she would like to take an “environmental awareness” trip to North Dakota.

In the past, he had often involved her in his activism, which was fine when she was a cute kid having her picture taken holding signs she didn’t understand. But as she got older, he’d become increasingly critical of what he called her lack of interest in the world, and since they saw each other so infrequently after he moved to Regina, his criticism eventually became the basis of every conversation they had, until he finally seemed to lose interest in her altogether.

“Just for one night,” he’d said, and she’d agreed because she felt sorry for him. She regretted her moment of weakness as soon as it dawned on her that one night meant sleeping arrangements would have to be made, and that the making of those arrangements meant that he must have considered the developments that had taken place since the last time she’d spent a night with him or, worse, that he might not have considered them at all. Now here she was with Holy Terror in her immediate future and the Motel beyond that, and all she wanted was her bed at home.

“This one is interesting,” said her father, who had calmed down since seeing a sign identifying the place as Greene, North Dakota. “The guy from Nukewatch told me that he was here when they planted it, and the farmer who owns the field was so horrified, he put his farm up for sale the next day. He thought it was going to be a batch of dynamite or something, not a forty-ton intercontinental ballistic missile!”

Ange pressed her lips together and nodded her head to indicate impressed surprise, but the truth was that measurements like this meant nothing to her. A ton, a kilometer, an acre — she was incapable of conceptualizing such abstractions. The world, to her, consisted only of the known, which had dimensions that could be seen and felt, and the unknown, which did not. Travelling through the prairies with her father, she had no sense of north or south or of what distance they were from Souris, let alone from the U.S.S.R., a place that occupied a dark corner of her imagination along with various other things so often discussed but never experienced, such as World War II and the nucleus of a cell.

Sex had occupied that same strange space in her psyche, casting its glow over all of the frightening things that dwelled there, until she’d allowed James Betker to finger her in the back of the school bus and then, two weeks later, let Matthew Cain take her to his hunting camp. “You taste like a peach,” Matt had said when they kissed on the dank futon under a lamp in the shape of a miniature guillotine, and although she’d found it unoriginal and somewhat comical, she had liked it. Feeling suddenly playful, she’d said, “I’m freezing” and moved his hand to her erect nipple, then, when he tried to take off her shirt, she’d jumped off the couch and said, “Let’s light the wood stove!” in a voice so foolishly childlike it made her blush.

Hurrying over to the stove, she had felt him pursuing her, but not in the way that she wanted him to. When she bent down to open the filthy glass door, he had grabbed her from behind and pressed his erection into her left butt cheek, and when she had turned to him looking pained and confused, he’d said, “You’d better be ready to finish what you started.” All at once, with a sickening disappointment that felt somehow familiar, she had discovered that she had no choice about what happened to her, and that the promise of power and something like glory that sex had once extended to her had proven, like everything else, to be a miserable lie.

When they arrived at Holy Terror, it was almost dusk, and the corn hissed like a field of punctured tires. Ange and her father got out of the car and approached the site in silence, her father heading straight for the sign that read, Warning: Restricted Area. When they got close, they heard the mechanical whirr of the security camera over the hum that came from inside the fence. “Hey,” her father said, waving. “We’re on Candid Camera.” He moved toward her to parody a happy family pose, but she stepped aside and gave both him and the camera a stiff smile as she stared at the concrete slab through the metal links.

The cold wind ruffled her windbreaker and made the fence shake. She could feel her bra coming undone in the back, and she found that she had the same feeling she used to get as a child when she had to call her mother in the middle of the night to pick her up from a sleepover. Some small thing, like bumping into her friend’s dad on her way back to bed from the bathroom, left her feeling shamefully exposed, caught in an act that was meant to be private.

He had brought the guidebook with him, and he opened it and showed her the page. “This is what it looks like under there,” he said, pointing to a heavily marked diagram of something that looked not unlike the things she’d seen Wile E. Coyote light with a match in Road Runner cartoons. “That thing is forty times more powerful than the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima. Can you imagine?”

What she had understood so far was that the concrete slab was a lid, under the lid was one of a thousand missiles that were buried under farmers’ fields across the prairies and aimed at the Soviet Union, and because of this they were all sort of doomed. When they’d first set out that morning and her father had begun his lecture, Ange had asked a few questions, such as how do missiles know where they’re going without someone driving and what if they hit a bird or a plane on the way, but after a while, she felt so impressed that someone had figured all of this out and so stupid for knowing so little that she just sat quietly and tried to react appropriately to what her father said without giving away too much. Specifically, she wanted him to think that she cared about the missiles without offering any accompanying indication that she cared about him.

“Just one of these could destroy an entire civilization in a second,” he said.

She made a concerned face. Of course he wouldn’t expect her to sleep in the same bed as him, she thought. There was no way he was that clueless. But even sleeping in the same room would be unbearably awkward and awful.

“And of course the Russians have missiles too. Can you guess where they’re aimed?”

She waited to see if he would answer his own question, as he often did. “Where?”

“Think about it.”

“I don’t know. Washington?” She knew that there was a D.C. and a state, but she didn’t know the difference and thought it was too late to ask.

Her father laughed. “No, they’re aimed right here where we’re standing, and if it happens, the prevailing winds would take the fallout directly northeast of here. Do you know what that means?”

“No.”

“Think about it.” She pretended to think about it until he told her the answer.

“Winnipeg would be wiped out, and we’d all get lethal doses of radioactivity. The Pentagon tries to pretend they’re here to protect us, but really they’re turning us into a human sacrifice to protect the big cities. Can you believe that?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well come on,” he said. “What do you think?”

She shrugged and wrapped her arms around herself, feeling miserable that the only thing she had to look forward to was an even more unpleasant scenario than the one she was currently enduring.

“I’m interested to know your opinion. Can you tell me your opinion?”

“Well . . . who has more, them or us?”

“It doesn’t matter, Ange. We have enough to wipe each other out. There’s no remainder, if that’s what you’re thinking.”

“Okay, so I guess . . . like, I hope it doesn’t happen,” she said.

“But doesn’t it make you angry?”

“I guess.”

“And do you think there’s anything you can do about it, or do you just want to wait and see what happens?”

“I don’t know,” she said.

“I guess, I guess, I don’t know.” He tensed his mouth and moved his head from side to side. “You don’t care, do you?”

She said, “I guess not” at the same time as he was saying, “You sound exactly like your mother,” then she turned and walked back to the car.

In Mohall, they ate pizza in silence, and she used a fork and knife instead of her hands. Afterwards, they made the short drive to the Motel, and her father’s knuckles were white on the wheel. “I’m sorry, okay?” he offered. “There are a lot of things that you don’t understand yet because I’ve never been willing to drag you into all that grown-up stuff.” He was quiet for a moment, then continued, “You know, your mother always cared more about outfits than anything we were trying to accomplish, and it’s because of people like her that it all went to shit.”

Ange looked out the window at a group of boys picking squashes and putting them in canvas bags slung over their shoulders. She thought about what her mother had said once: “Ever since you hit puberty, he turned on you. It was like he didn’t trust himself around you.” Ange knew it wasn’t true and that her mother had said it purely out of spite, but it had planted a seed, and that was all it took.

“What I mean,” her father said, “is that it’s not your fault.”

The outside of the Motel was the most dreary thing Ange could imagine. The parking lot was empty apart from an old blue pickup, and there wasn’t one person in sight. The radio was on in the truck, and country music blared out of its open door over the sound of an argument in one of the units. Ange decided to follow her father to the office so she could find out what the sleeping situation was before she was confronted with it in the room. As they walked, she tried to make out some of the argument, but all she could hear was a woman screaming, “No! This is bullshit!” again and again.

In the office, there was a ginger cat on the counter, and Ange stroked its fur while her father spoke to the fat man behind the desk.

“Sign here,” the man said before bending down with a loud groan and reappearing with a set of keys.

“You’re in number twelve. License plate number?”

“Why do you need that?”

“I need it if you want to park outside your unit.”

“Do you have paper and pen?” her father asked, clearly annoyed. The man pushed both across the desk and Ange’s father left without looking at her.

“He likes you,” the man said once Ange’s father was gone. “He doesn’t let anybody pet him normally.” Ange scratched behind the cat’s ears and under his chin. “What’s your name, honey?” the man asked. Ange could feel him scrutinizing her tits. People thought they had a right to do that. Everyone felt free to comment and stare.

“Ange,” she said, pronouncing it the way the kids at school did, not Ahnj, as her mother said it.

“You enjoying your holidays with your daddy?” the man asked. Ange moved her hands to the cat’s rump, digging her nails in and massaging above his tail. The man leaned forward and his voice became confiding and soft. “He is your daddy, isn’t he, honey?” he said. Suddenly Ange understood what he was getting at, but in an instant her outrage disintegrated against her will into tears, which fell down her cheeks with the fat man watching, so that she had to run out of the office like a fool.

“Hey, where are you going?” Her father, who was on his way back into the office, called after her as she walked away from him down the row of numbered doors.

“To find the room,” she said, furious beyond all reason. She had no patience for tears. When her father went to live in Regina, her mother had cried for what seemed like years. Ange had felt her mother’s crying in her guts. It tugged like a fish hook in her, and she went toward it not out of love but out of fear of being ripped apart. She would find her mother in her bedroom or in the closet or in the basement, and she would kneel next to her and stroke her hair and say, “It’s all right. It’s ohhkay,” until her mother stopped or fell asleep.

It took him so long to come to the room that she started to wonder if he had driven off without her. She had been sitting on the concrete stoop outside, swatting at bugs attracted by her blood and the fluorescent lights. He was silent as he opened the door and as they both went inside, but she could tell that something was wrong. She barely had a chance to notice that there were two double beds in the room before he spun around to face her.

“What the hell is wrong with you?” he shouted. “That man thought I was some sort of criminal.” His face was red and spit spattered his lips. Part of her wanted to laugh, because she had never seen him so out of control. “Do you have any idea how embarrassing that was for me?” She kept walking toward the bathroom, planning to lock herself in and make a bed of towels in the bath, but as she passed him he grabbed her hard around the fattest part of her arm and turned her around so they were face to face.

It was the first time he had touched her in years, but it wasn’t his roughness that made her feel violated, it was the intimacy of his hand against her bare skin. Feeling an urgent need to reverse what he had done, she leaned forward and bit into the soft flesh of his shoulder. Her teeth almost penetrated the skin before he socked her on the right side of her head and she fell, ears ringing, onto the brown carpet.

When she opened her eyes, she was lying on her side, her cheek pressed into the disgusting carpet. Her father kneeled down and she covered her face, expecting him to hit her again, but instead he tried to move her hands. She started to turn on her belly to get up, but he grabbed her around her waist from behind. They struggled on the floor. His arms reached around her on both sides, and he grabbed his right forearm with his left hand over her chest. He wound his ankles around her legs to stop her kicking him.

Her cheek was stinging and hot, and warm liquid leaked out of her nose and into her hair. An opened safety pin had stabbed her right shoulder, and she could feel it working its way in rhythmically with her sobs. The sound of her own crying infuriated her, but there was nothing she could do to stop it and trying only made it worse, so she gave in and told herself that everything was totally ruined. She couldn’t stop crying and she couldn’t make him let her go, so she just lay in his arms and thought about being ruined until he lifted her onto the bed and rocked her to sleep.

When she woke up it was morning. Her face still ached, and her head felt heavy. She could hear him in the shower. She tried to sit up, but when she lifted her head she discovered that it was stuck to the stiff orange top quilt, the one that her mother had always told her to remove before sleeping in a hotel bed because they were never washed. She slowly peeled the quilt away from her face and turned to see that the other bed was still made.

She stood and went over to the wardrobe mirror. One side of her face was bright pink, and there was dried snot caked under her nose. She undid the top two buttons of her shirt and lifted one sleeve over her shoulder to see where the safety pin had stabbed her. The tip had punctured her skin just below the shoulder blade, but it was easy to pull out, so she just refastened it through two loops in the strap of her bra, did her shirt up, and pushed hard on the place where the pin had been to soak up any blood in the flannel.

It was weird how okay everything felt, even with the bathroom door about to open and not knowing how her father would behave. She sat on the bed and waited, and when she got bored with waiting she turned on the TV and flipped through the channels.

When her father came out of the bathroom, he was holding a steaming face cloth. He offered it to her, and she pressed it to her cheek. She thought he looked like a little kid who doesn’t know what to do, and she felt sorry for him, but the feeling was different than the one that had made her agree to the trip. He watched her dab her face with the face cloth, and then they both silently packed up their things and took their bags outside.

“Do you have the guidebook?” he asked as she climbed into the car. She closed her door, opened the glovebox and showed him the book, then put it away again. When both of their seat belts were on, he lifted her hand from her lap and squeezed it in his until it almost hurt. They stayed there for a minute, staring at the grimy white vinyl exterior of the motel, a heavy pulse between their fingers.

As they drove home, they passed the squash boys again, and she waved to them, but they didn’t see her. Then came two fields of wheat, one on either side of the highway. There was more wheat there than she had ever imagined was possible. It went on and on. There must be enough to feed the whole country, she thought. There must be enough, probably, to feed the whole world. And to think that there were people who knew how to harvest it and turn it into flour, and other people who knew how to turn flour into bread. How clever people were, she thought, and how much there was of everything.