Lit Mags

Anything for Money

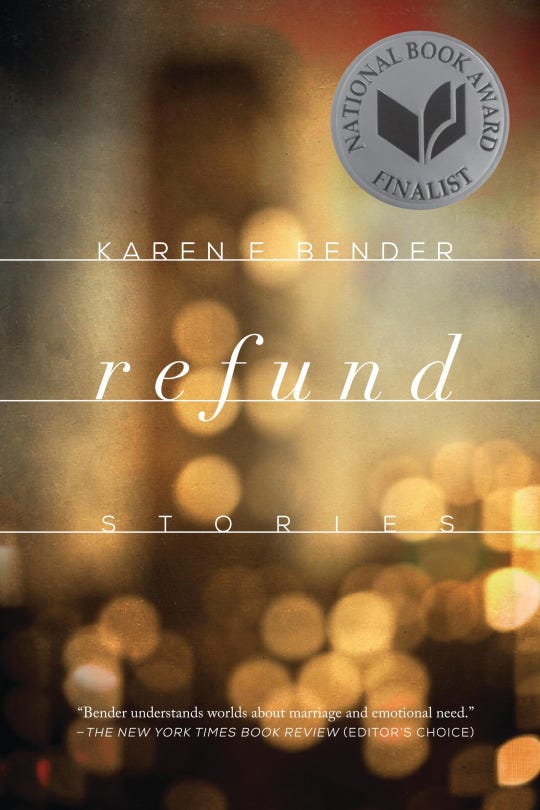

A short story by Karen E. Bender, Recommended by Counterpoint

INTRODUCTION BY DAN SMETANKA

What is your life worth? What is any life worth? These are provocative questions that hover over Refund by Karen E. Bender–now a Finalist for the National Book Award — a collection of stories that ultimately explores the emotional and economic devastation in the country since 9/11. In “Anything for Money” we see these questions examined through a most modern vehicle: a television game show. The wealthy producer of a show that watches people put themselves in awkward (and often debasing) situations for money finally learns the limits of what his great wealth can buy when his estranged granddaughter, who has recently and unexpectedly come to live with him, becomes in a need of a new heart.

What is your life worth? What is any life worth? These are provocative questions that hover over Refund by Karen E. Bender–now a Finalist for the National Book Award — a collection of stories that ultimately explores the emotional and economic devastation in the country since 9/11. In “Anything for Money” we see these questions examined through a most modern vehicle: a television game show. The wealthy producer of a show that watches people put themselves in awkward (and often debasing) situations for money finally learns the limits of what his great wealth can buy when his estranged granddaughter, who has recently and unexpectedly come to live with him, becomes in a need of a new heart.

Will he use the show to seek out those who will offer up their lives in exchange for money? Will his granddaughter’s frailty lead him to realize that there are some things — essential, transcendent things — that are, horrifyingly, priceless? The line between want and need then becomes as thin as the membrane between life and death, and what is so moving about these characters is how they navigate that torturous, fragile space. So many of Bender’s stories do this to great effect: they force us to confront our strong will to live while grappling with our often fragile existence. We’ll need full hearts, even with empty pockets.

– Dan Smetanka

Executive Editor, Counterpoint Press

Anything for Money

Karen E Bender

Share article

by Karen E. Bender

Each Monday at eleven o’clock, Lenny Weiss performed his favorite duty as executive producer of his hit game show, Anything for Money: he selected the contestants for that week’s show. He walked briskly across the stage set, the studio lights so white and glaring as to make the stage resemble the surface of the moon. In his silk navy suit, the man appeared to be a lone figure on the set, for his staff knew not to speak to him or even look at him. He had become the king of syndicated game shows for his skill in finding the people who would do anything for money, people that viewers would both envy and despise.

The assistants were in the holding room with the prospective contestants, telling them the rules: No one was allowed to touch Mr. Weiss. Mr. Weiss required a five-foot perimeter around his person. No one was allowed to call him by his first name. No one was to be drinking Pepsi, as the taste offended Mr. Weiss. Gold jewelry reminded him of his former wife, so anyone wearing such jewelry was advised to take it off.

He stood by the door for a moment before he walked in, imagining how the losers would walk, dazed, to their cars, looking up at the arid sky. They would try to figure out what they had done wrong. They would look at their hands and wonder.

Then he walked in, and they screamed.

He loved to hear them scream. They had tried to dress up, garishly; polyester suits in pale colors, iridescent high heels. The air reeked of greed and strong perfume. Some of the women had their hair done especially for the occasion, and it shimmered oddly, hardened with spray.

“Pick me!”

“We love you, man!”

“We’ve been watching forever!”

A woman in a rhinestone-studded T-shirt that said Dallas Cowboys Forever lunged forward, grabbed his arm, and yelled, “Lenny!”

“Hands OFF Mr. Weiss!” shouted the security guard.

There was always one who was a lesson for the others. The door slammed, and the woman was marched back to her life. They all listened to her heels clicking against the floor, first sharp and declarative, then fading. The others stood, solemnly, in the silence, as though listening to the future sound of their own deaths.

They were all on this earth briefly; for Lenny, that meant he had the burning desire to be the king of syndicated game shows, one of the ten most powerful men in Hollywood. He did not know what the others’ lives meant to them, just that they wanted what he had. Money.

Now he needed to choose his contestants. They would be the ones with particularly acute expressions of desire and sadness; they would also have to photograph well under the brilliant lights.

“All right!” He clapped his hands. “You want to be rich? You want other people to kiss your ass? Well, listen. You’re going to have to work for it. Everyone!” He knew to change his requests for each new group; he did not want any of them to come prepared from rumors off the street.

“Unbutton your shirts!”

He knew this one was more difficult for the women, but that was not a concern to him. Some of the people stiffened, pawed gingerly at their buttons. Others tore through their buttons and stood before him, shirts loose.

“Take off your shirts!”

He lost a few more with this request. Others removed their shirts as though they had been moving through their lives waiting for such an order. They stood before him, men and women, in bras and bare chests, some pale, some dark, some thin-shouldered, others fat.

“Repeat after me. Say: I am a fool.”

He heard the chorus of voices start, softly.

“Louder! Again!”

Their seats had numbers on the bottoms; he knew immediately whom he would call back. He would call Number 25, the woman with the lustrous blonde hair, and Number 6, the man with the compulsive, bright smile. Lenny clapped his hands.

“Thank you. My assistant will contact those who have been chosen.” Lenny turned, almost running down the hallway. He walked around for fifteen minutes before he could get back to work.

He had grown up in Chicago in the 1940s, the only child of parents who had married impulsively and then learned that neither understood the other; Lenny dangled, suspended, in the harsh, disappointed sounds of the house. His father died when Lenny was eight. Lenny’s mother moved them to Los Angeles and got a job as a secretary at one of the movie studios. The boy was shocked by the desert light, the way it made everything — the lawns, flowers, cars — appear stark and inevitable. His mother was the only person he knew in this world, and at first, when she left him at school, he was wild with fear that she also had disappeared. He pretended he was collecting clouds to make a wall around her, and when the sky was cloudless, he pretended he was sick. Then his mother brought him to the place where she worked. He sat on the floor watching her, and then everything else going on around her, too.

When he graduated high school, he became an errand boy on a soap opera, then a writer. He enjoyed making bad things happen to other people: troubled marriages, sudden illnesses, kidnappings. He married a woman who was impressed by his job and his descriptions of various actresses on the set. They had a child, a girl. Then one day the producers gathered all the employees into a windowless conference room. “There’s no more show,” they said.

It was the recession of the early 1970s, a bad time for hiring in any field, and he and his wife had little savings. He looked for work for six months without luck, setting his sights lower and lower, but already there was an odor of desperation on him. One night, his daughter was screaming in pain from an ear infection, but he was afraid to take her to a doctor for what it would cost. The child’s pain so horrified him that he bolted out of the house.

He did not stop running for several blocks. Strangers walked down the street, their wallets bulging with money he wanted. The money was so close to him, he could almost smell its dusky green scent. His jaw hurt. Suddenly, he had an idea: he could rob a liquor store. He had thought about how to do this when he wrote his soap operas. The simplicity of this idea made him stop in astonishment. He could wear a stocking over his face and stuff a bottle in his jacket pocket as a gun.

There was a liquor store a few blocks away, and he stumbled toward it. Lenny stood outside the liquor store for a long time. He sobbed softly. His tongue tasted like a dry, bitter leaf. The other customers entered the store, noble in their morality and their innocence. He had become this: a man who would do anything for money.

Later, he would tell people that this was the moment he became God — for he had saved himself. Anything for Money could be a show in which contestants would do terrible, absurd things to receive vast amounts of money.

The next day, he sat for ten hours in the waiting room of his former employer. When Lenny saw the head of programming, Mr. Tom Lawrence, come out, he hurtled toward him, thrusting out a proposal. “Read this,” he told Mr. Lawrence. Lenny did not know why the man decided to listen to him, though he understood, in an honest part of himself, that it was simply a grand moment of luck. Later, he chose to describe this as a sign of his own inherent glory. Mr. Lawrence took the thin sheet of paper, folded it in half, and stuck it in the pocket of his blazer. Lenny watched him walk off. A month later, Mr. Lawrence bought the idea for the show.

Now he was sixty-five, the show’s executive producer, and his limousine took him from his studios to his home in the hills above Los Angeles. As a young man, he had never quite believed the success of Anything for Money, the way his longing formed itself physically into homes, boats, cars. He used to wake up with his heart pounding as though he were running an immense race. His daughter and wife were mere shadows to him, for he needed to get to the studio with a breathless craving. He was there from eight in the morning until eleven at night.

Thirty years ago, his wife, Lola, left. He blamed his wife’s leaving on her excessive demands; many of his colleagues’ wives had left them, too. The few times he had seen her since she left, she looked entirely unfamiliar to him. It seemed that he had not been married to her but to a lookalike who resembled her. She had come up to him at a party and said softly, “You never knew anything true about me.” When she said this, he felt deeply wounded, felt his honest attempts at goodness had been misunderstood. All his attempts at romance had been clichéd — he bought her diamonds, midnight cruises, silk gowns. “All I wanted,” she said, “was a poem written about my eyes.” He stood before her like a little boy. Did this mean they had not loved each other?

His memories of his daughter were glazed with exhaustion. Charlene stood, naked in the bathtub, water streaming down her tiny body, a pale angel absolutely convinced of her own glory; he could not believe she had come from him. Sometimes Charlene clung to him with such fierceness, such pure trust, he felt himself crumble inside. He was afraid she would see in his eyes the weakness of a lame dog and laugh at him. She was a toddler running, stiff-legged, across the lawn, then she was six and running, legs outstretched, like a small antelope, in gaudy, colorful clothing; then his wife left and he could not see his daughter running.

Charlene believed that he had kicked them out of the house. That was what Lola had told her. He tried to explain to her that this was not the truth, but she said, bluntly, “Mom said she asked you thirty times to stay at home for my fifth birthday. And you did not.” He did not remember any of these requests. He had thought he belonged to a family, but suddenly they accused him of misdeeds and crimes that made him — and them — unknowable.

Charlene called him only to request money, which he always gave her. He once heard her on a talk show denigrating him with a fictional story: “My father was so self-centered he had a special mirror only he could look into. If anyone else did, he’d tell us it would crack.” Much audience laughter. Lenny would not hear from her for months, and then he’d get a long letter, dissecting injuries done during her childhood; she had been arguing with him in her mind the whole time. Then, when he called her to discuss the letter, she would hang up on him.

The calls came more frequently immediately after Lola’s death. His ex-wife had died in a car accident fifteen years ago; she was gone, and his remnant feelings for her were interrupted — he still had not divined whether they had loved each other or not. Charlene seemed to hope that, as her only living parent, he would have the capacity to read her thoughts. He sensed then how remote she felt from other people. When he could not read her thoughts, she reacted with anger so forceful it was as though he had told her he hated her.

Over the last fifteen years, he heard about her mostly through gossip items in the paper: Charlene Weiss sub eatery sinks. Charlene Weiss briefly hospitalized for alcohol abuse. Charlene Weiss has fling with Vance Harley, sitcom star. Charlene Weiss has daughter, Aurora Persephone Diamantina Weiss. A quote from the happy new mom: “I have reached a pinnacle of joy.”

She did tell him about Aurora. She had become pregnant from one of her many suitors and decided to have a child on her own. He received an elaborate birth announcement, a silver card with a photo of the baby girl swathed in white robes like a tiny emperor. The inscription below the picture said: Aurora: A Child Who Will Be Loved.

For thirty years, he lived alone in his mansion on top of the Santa Monica Mountains; he had told his architect that he wanted to feel he could put his hands on the entire city. He could see all the way to the Pacific Ocean, the expanse of ocean like black glass, all the way to the luminous blocks of downtown, to the cars pouring, twin rivers of red and white lights moving east and west, north and south. His loneliness had buried itself deep within him, and he experienced it as the desire to be in the seat of every car. The architect had set his living room at the edge of a hill, so that when Lenny looked out his twenty-foot-high glass windows, he almost believed he could fall into the trembling party of lights. He stood there many nights, full of longing so deep he could not name it; he was aware only of his quiet desire to thrust himself into the dark air.

The call came in his limousine following a meeting with the producer of the talk show Confess! His maid’s voice floated over the speakers.

“Mr. Weiss,” Rosita said. “Come home.”

“Why?” he said to the air.

“A child is here.”

“I don’t know any child.”

“Her name is Aurora.”

He stared at the speaker.

“Yes,” he said. “I know her.”

When they reached his house, Lenny stepped out of his limo. His home was made of pale marble, and clear white wavelets from the swimming pool shimmered on its empty walls. Black palms, bathed in blue light, swayed in the warm wind. The bushes in his gardens had been trimmed to the shapes of elephants, giraffes, bears, and they made a silent, regal procession through the darkness. He stood for a moment, in the quiet he had made, before he went inside.

The girl stood at the top of the stairs. He would not have been aware of her but for the ferocity with which she stood there, as though she had dreamed herself in this position for years. She was gripping the railing, staring at him. Her face was dim, but he could see her fingernails holding the rail — they were an absurdly bright gold. She ran down the stairs so fast he thought she might fall.

“Hello,” she said.

His legs felt as insubstantial as water. He looked at Aurora. He believed she had to be about twelve years old. Her face had the hard, polite quality of someone who had been scheming quietly and fervently for a long time. Her auburn hair reached halfway down her back. She had Lola’s eyebrows, two arched Us that gave her an alert, surprised expression. She had Charlene’s navy blue eyes. They were the color of steel and moved around restlessly, but they had a hard gaze when they settled on something. He knew because they were also his eyes.

“Hello,” he said. He offered his hand. She grabbed it. He still wore the Bluetooth headset he usually wore so as not to miss any calls.

“What are you doing here?” he asked.

“I was sent.”

“By who?”

“My mother.”

She handed him a letter. The letterhead said:

BUENA VISTA REHABILITATION CLINIC

Your secrets are ours.

Dad —

I am here for the next three months.

Take care of Aurora.

She likes chocolate.

I’m so tired.

Charlene’s signature resembled a tiny knot.

The letter’s tone was so polite he knew that she had been trying to please someone watching her as she wrote it.

“Is this where your mother is?”

She nodded and stepped carefully toward the enormous living room windows. “This was in a magazine,” she said.

“House and Garden,” he said.

She nodded. “It’s bigger in real life.”

He wanted to stop her. She was standing against the window, pressing her fingers against the glass. He saw her make a breath on the glass, a pale oval, and the intimacy of the action made him want to walk away.

Two large suitcases sat in the foyer. He gestured to them and said, “Carlos can take them up for you.”

Aurora rushed up to one and grabbed the handle. “No!” she said. “I want to do this one myself.”

The bag was not actually a suitcase, but a large green canvas sack. It bulged, oddly, with unidentifiable objects.

“You can’t carry that yourself,” he said.

She looked pleased, as if she’d predicted he would say this. “Then you help me.”

He could not even remember the last time he’d carried anyone’s bag, including his own. “Rosita, call Carlos,” said Lenny.

“No,” said Aurora. “You.”

Rosita brought him a dolly, and he pushed the bag into the elevator. The girl walked beside him, fiercely gripping the bag handle. The elevator rose to the second floor. When they got to the guest room, he stopped.

“You can stay here,” he said.

She walked in, dragged the bag into a corner. “Thank you,” she said.

“Good night now,” he said.

Her eyelids twitched. “I’m not sleepy.”

He began to back away. “Hey, look,” he said. “I’m sorry. You’ll

have to entertain yourself. You know.” He lifted his hands helplessly. “Sweeps. Nielsens. I don’t have time for babysitting. Rosita,” he said. “Aurora will be visiting us. Bring her hot chocolate.”

Aurora stepped back and stared at the floor. She looked as though she had fallen from the sky.

He felt he should say something more to her, but did not know what.

“Rosita, put some whipped cream on her hot chocolate,” he said, and he fled.

Lenny woke with a shudder in the middle of the night. He sat, his heart marching, in his bed. Then he got up and went to the kitchen. He sat in the blue midnight and drank a glass of milk.

He heard footsteps — peering through the doorway, he saw Aurora in the foyer. The girl was walking barefoot, in her pajamas, through the enormous room. She made almost no sound and moved through the darkness in a careful, fevered way. She went up to the statues, lamps, couches and touched them tenderly. She walked quickly, from room to room.

He fled back into his room. He was shaken, furious, wondering if he should wake Rosita, call the police. The girl was walking through his home. Now it seemed that anything could happen — the clock could walk off, the curtain could burst into flames. He lay awake for a long time.

He woke up at six, far earlier than he believed the girl would be up. After he made his way down the stairs, he realized that his headset was gone. He had left it on the kitchen table after his midnight glass of milk, and its absence made him feel anxious, excluded from the news of the day. He ran to Rosita and asked her to look for it. He would give himself twenty-five minutes for breakfast. About ten minutes into his food, Aurora walked in. She stood, a little tentatively, in the doorway; her face was carefully blank.

“Hello, Grandfather,” she said. She said this title loudly, as though they both should know what it meant.

“Hello.”

Her face was heavy with exhaustion. She sat at the other end of the table. Before she did this, she moved a large crystal urn of flowers to the floor.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“I want to be able to see you when we talk.”

He eyed her and ate a forkful of eggs. Rosita placed a croissant before her. Aurora was staring at him, drumming her fingers on the tablecloth.

“I have a question.”

“Yes?”

“How does it feel to be syndicated in forty-three countries?”

“Forty-four. Somalia just signed on.”

“Forty-four.”

“Very good.”

“Your first episode of Anything for Money had the biggest television audience ever.”

“That is true.”

“How did you get Ringo Starr to do a guest spot?”

“He asked to come on.” He looked up. “Is this an interview?”

“I’ve read 127 articles about you. In all the major magazines. More on the Internet. On the authorized sites.” She went through four slices of bacon. “Is it true that you only stock water in the back of the set so that contestants will get hungry and meaner?”

“No.” He lifted the paper in front of his face. “Anything you need, ask Rosita.”

“I would like an office.”

He lowered the paper. “For what purpose?”

“The production of my feature film.”

He folded the paper.

“I am currently in preproduction.”

“You are twelve years old,” he said.

“I know,” she said, as though that were a compliment. “I have read many books on the subject. I am writing a script. If you want to know the title, I can — ”

He marched out of the dining room; she followed. He was not used to waiting for another person, and he could sense her trailing behind him, trying to catch up.

He pushed open two doors embossed with a gold pattern identical to the doors of Il Duomo in Florence. The room overlooked the rose gardens.

“Your office,” he said.

She seemed surprised that her request had been obeyed so swiftly; then she walked in, hands clasped behind her back like Napoleon inspecting the troops. She went to the windows and looked outside. The morning sun fell in wide bright strips across the lawn, so that the pink- and cream-colored roses gleamed like satin.

“Do you require use of a phone?”

“No,” she said.

“A fax machine?”

“No, thank you.”

She rose up on half-toe and then down again — later, he realized this was the gesture she used when she had more on her mind that she wanted to talk about, trying to make herself physically taller to give herself stature to ask for what she wanted.

“Your office,” he said. “Now. My headset.”

“Your what?”

“My headset. I need it.” He tried to smile, attempting to appear more relaxed than he felt. “Now.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” she said, curtly, so like her mother in fact it confirmed she knew where it was. She sat in the dark vinyl chair and leaned back in it. “Now. Tell me your opinion. I want to describe the sky over a new planet that has been created by the explosion of a supernova. Should it be pink or yellow or blue or a combination?”

“I don’t know,” he said.

“Pick.”

Her stubbornness made it hard for him to think. “Blue,” he said, helplessly.

She spun the chair.

“Thank you. I have to get to work.”

Lenny drifted through his day at work, listening to his writers knock around ideas: How about having contestants drink a concoction made by a four-year-old out of items he found in the refrigerator and medicine cabinet? What about telling people they had to walk down the street dressed like a chicken, slapping every third person on the face? That’s Anything for Money! When he left, the sky was dark and furred with purple clouds. He told the chauffeur not to drive him home immediately. He was glad for the sensation of motion as the car floated over Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, Silver Lake; he did not want to be still.

When he got home, he found the staff assembled in the living room. They were clutching pieces of paper. Rosita was wearing a large pot holder on her head. Carlos was wearing a cape. He saw other employees, whose names he did not remember: a gardener wearing a chiffon scarf around his neck, the pool man. Aurora was standing on a chair in front of them. They were listening to her.

“Rosita!” Aurora commanded. “Your turn!”

“You! You have cursed me!”

“It is what the forces said to do,” Carlos said, in an eerie voice.

“Hello,” Lenny said.

There was a silence. Rosita took the pot holder from her head. Carlos removed his cape and smiled brightly.

“What is going on?” asked Lenny.

“We’re rehearsing,” said Aurora.

“For what?”

“My movie.” She smiled. “They’re all good in their parts. I didn’t know they all wanted to be actors!”

He had not known that they had any other aspirations at all. He studied them. They looked away, trying to erase the animation in their faces.

“Thank you all,” she said. “We’re done.”

Carlos picked up Lenny’s briefcase and walked, stiffly, up the stairs.

“Rosita! My dinner,” Lenny ordered.

“Can I have mine, too?” Aurora asked.

“You haven’t had dinner?”

“I wanted to wait.”

“Children shouldn’t eat at nine o’clock,” he said. It occurred to him that he had no idea when a child should eat dinner.

“I always wait for my mom to come home.”

“When is that?”

“Six. Nine. Never.”

“What do you eat when it’s never?”

“Whatever’s around. Yogurt. Ritz Crackers. Raisins. Chips.”

“Rosita, give her some dinner,” he said. He went to his room.

He entered his bedroom and changed into his silk sweat suit. Then he looked for his favorite comb. It was not in his bathroom or his bedroom; nor could he locate his cologne. Standing in the middle of his bedroom, he wondered what the hell was going on. He went to the balcony and listened; he heard the clatter of a fork and knife; she was eating. He went down the hall to Aurora’s room and opened the door. The large green sack was on the floor; he unzipped it. It was full of small brown paper bags. One was marked MY GRANDFATHER LENNY; inside was his headset and his comb and cologne. He peered into the other bags. One was marked MADAME FOURROUT, and inside was a postcard of Paris, a snapshot of a friendly baker, and a wooden spoon. Another bag said SAM FROM OXFORD, and inside was a snapshot of a college student and a silver pen engraved with the initials SNE. There were men and women of all ages and nationalities, and their toothbrushes, cosmetics, office supplies. The people represented in the bags were from Paris, Milan, Athens, Buenos Aires, everywhere that Charlene and Aurora had lived.

He zipped up the sack and walked out of the room, embarrassed by what he had just done. Embarrassment was an unusual feeling for him — he mostly encountered others experiencing it — and he did not know what to do. His chest felt empty, and he had to sit down, waiting for the feeling to go away. He did not know why she had taken these objects from these people, but he believed he understood in some way as well.

Lenny did not come to the table for another half hour. He was shaken and did not want her to see him. But when he came into the room, she was still there, waiting for him.

She was eating very slowly, scraping the sauce from the poached salmon off the plate. He was not used to anyone waiting for him at the dinner table. He was used to the mobs surging, gray-faced, in the holding room, staffers pacing, tense, outside his office. She was spelling her name in the sauce: AURORA.

He strode in quickly and took his seat. She had removed the urn again.

“I was a little hungry,” she said.

He could see now that she was enormously tired, that she had spent her life keeping herself awake far longer than she should have.

“So,” he said. “Time to get to know each other.” His laughter fell into the room. Rosita brought out a tray filled with glistening pieces of sushi. “Where were you and Charlene most recently?”

“Paris. Vienna. Argentina. We had a fine time — ”

“What do you do there?”

“I hang around. I’m sociable.”

“What does your mother do?”

“She is busy.” She shook much more salt on her dinner than was necessary.

“Doing what?”

“Many people want to know her.” Her hand gestured grandly in the air. “You know, she started her own line of baby clothes. Le Petit Angel. She was going to work with Christian Dior — ”

“Before she got thrown into rehab?”

“No!” she cried out, and her voice curved, suddenly, into a wail. She looked into her lap and pressed her hands against her face. Then she glanced past him and said, quickly, “I want to talk about success. I want to be a success. I have my own theory — ”

“What is that?” he asked.

She sat up. “Success is about keeping your eyes open. Being organized. Having a plan. Getting to know people — ”

“Success is luck,” he said. “Some people are winners. Some are not.”

She gazed at him with an expression that straddled, equally, opportunism and love.

“I have created the most successful show on television. One quarter of the world watches my show.” His voice was husky, honeyed; he wanted to convince her of something. “The ones who win, they’re lucky. They get the question they know how to answer, or they called the office the moment we needed to fill a show.”

“What about the unlucky ones?” she asked.

“We need them, too. So people are grateful not to be them.”

She was listening.

“We’re choosing contestants tomorrow in Las Vegas for a special episode there. To be broadcast opposite the Super Bowl.” He punched the air enthusiastically. “Why don’t you come see how I do it?”

He could not look directly at the joy in her face; it blazed with a terrible brightness.

He took her in his private jet, the jet that he had Lockheed build for him on a special commission. The earth fell away, the ocean a swath of silver, Southern California suddenly silent and remote; he looked out the window, and he felt a sweet relief blow through him.

He took a break from the planning session and grandly walked her around the plane, making sure the staff was watching. “This is my granddaughter Aurora — I’m telling her how to become a success. Aurora, here is the plane sauna. My staff tells me that anyone of any stature must have one of these on a plane. Over here, the plane game room, this is the biggest pool table in the sky… ”

They landed in Las Vegas and set up their camp on a full floor in the MGM Grand. On the show, the contestants were going to run naked through a large, slippery pit filled with bills, trying to grab as many as they could. However, they would be allowed to use only their teeth. Some of the bills would be ones, but some would be thousand-dollar bills. Most of the plane trip had been consumed with discussion of whether to use olive oil or Crisco for the pit. The contestants would have to look good naked, be adept at sliding on curved surfaces, and have large mouths. Hundreds of people showed up and were funneled into a large conference room, where they were instructed to wait until Lenny arrived. He told Aurora to sit in the room with the contestants so that she could hear his staff prepare them.

The group looked like they’d been up late for too many nights — their eyes were rimmed violet, their hair desert-burned. They had been around the prospect of instant luck for too long, and they looked worn but grimly entitled.

Lenny walked in. “All right!” he shouted. “You want to do Anything for Money? Show me!” Their eyes were set on him. “You, what’s your name?”

“Betty Valentine.”

A slight woman came up. She had the blank, watery expression that meant she had been dragged here by a friend; she was in her forties, with short pink-blonde hair.

“What are you worth, Betty Valentine?” He pulled a wad of bills from his pocket. “Five dollars? Ten? A hundred?” He flicked the bill against her nose; she blinked. “A thousand?” He let the bill fall to the floor. Everyone regarded it with interest.

“Two of those are yours. If you can sing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’”

Betty smiled slightly: this was easy.

“In here.”

He snapped his fingers. An assistant rolled over a ten-foot-high wooden box. He opened a door. Inside, a hundred cockroaches were crawling on the walls. Betty’s face was still.

“Come on, Betty.”

Betty looked around at the others; putting her hands over her face, she slowly stepped inside the box. Her arms were shaking. Cockroaches crawled all over the insides of the box, onto her arms. She covered her face with her hands and began to make a high-pitched sound.

“Sing it!” he said.

Betty coughed. “Ohhh, say…” her voice trailed off.

“We’re waiting,” he said.

“Oh, say.” She stopped and ran out of the box.

“Stop!” he said. An aide nimbly scooped the thousand-dollar bill off the floor. “You call that singing? Are you winners or losers?” Lenny shouted at the group. “What are you worth?” His voice boomed. “Betty couldn’t take it, could you?”

There was the sound of someone running behind him; he was appalled that anyone had moved. He whirled around to see Aurora standing up, her hands balled into fists.

“STOP!” Aurora yelled at him, and she ran out of the room.

The room went still; Lenny lunged through the doors. She was walking with stiff steps down the hotel hallway.

“Aurora!” he yelled. “Why did you do that?”

She spun around. Her face was pale. “You were a jerk.”

“Hey,” he said, lightly, “this is my job.”

She began to run away from him.

“Wait,” he said. The sight of her running away — from him — made him start, quickly, to follow her. “Aurora. Stop.”

He remembered how, as a toddler, Charlene would run around the garden, talking to the flowers. “You are Astasia,” she once said. “You are Petunee. You are Clarabell.” Her innocence was so pure it was almost grotesque. He remembered how she would run up and kiss him, her mouth wide open, as though she were trying to consume his entire cheek.

“Aurora. Why did your mother send you to me?”

Aurora stopped. She scratched her leg. “I don’t know.”

“Why?”

“There was nowhere else to go.”

He stood, dizzy, watching her run from him; then he told his staff to take over for the afternoon. He walked through the hotel, past the slot machines, where the sounds of people hoping to change their lives were as loud as a thousand bees. He continued through the cocktail lounge, the cigarette smoke a silver fog. He pushed through the hotel exit and stared, trembling, at the pure blue sky. He, too, believed he had nowhere to go.

It was dusk when he finally found her. She was sitting on a bench, staring at a fountain surrounded by arcs of blue light. He approached her slowly. He did not know what he wanted, but he felt just as he had many years before, when he was about to rob the liquor store — as though he wanted to grab hold of the universe and change it. Then what he had wanted was practical. This universe he wanted to change with Aurora was different; it was abstract, constructed of feelings, and he did not know how to live within it.

“Aurora,” he said.

“What do you want?”

He stood before the girl, an expensively dressed man, worn down, sweaty, against the dark Las Vegas sky. “I’d like to talk to you,” he said.

She shrugged.

He sat down and leaned forward, clasping his hands. “What’s the title of your movie?”

“Why?”

He shrugged. He did not know what else to ask.

“Danger,” she said, a thrilled edge to her voice. “This is the poster. It’ll have a picture of an exploding world. There will be huge clouds of smoke. People from other planets will pick up stranded earthlings in their rockets. The saucers will fly through violet rain…”

“Danger,” Lenny said, slowly; it seemed a beautiful word. “It is a great idea.”

The next day, the jet took them back to the mansion. They walked the grounds together, and Lenny showed Aurora the whole estate, but mostly he listened to her tell him about her film. The girl spoke quickly, desperately. The plot of Danger was unclear but enthusiastic. It involved runaway missiles, a child army, aunts possessed by aliens, and other complex subplots. Lenny’s contribution to the conversation was to not interrupt. If he did, the girl became furious. Aurora had thought through many of the marketing elements: the poster, the commercial. She wrote the title of the movie on a piece of poster board, decorated it with pieces of red velvet. She became so passionate during her description of the trailer for Danger that she got tears in her eyes.

He was not sure what they should do together. His jet took them to Hawaii one weekend where she could swim with dolphins, and to London the next for a lavish tea. He imagined that intimacy would feel like the sensation he had when the jet swung up into the sky, a feeling of airiness, of vastness; but she was not interested in the green sea around Hawaii, the heavy, sweet cream spooned around a scone. Instead, she wanted, strangely, to talk. She wanted to know the smallest, most peculiar details about him. What was his favorite color? What was his favorite vegetable? What kind of haircuts did he have as a child?

One day, she asked him what he was most afraid of in the world.

“You first,” he said.

“Spiders,” she said.

“Snakes,” he said.

She looked dissatisfied. “Something better,” she said.

“Earthquakes.”

These were lies; he really had no idea.

“Ticking clocks,” she said.

“Why?”

“When my mother doesn’t come home,” she said, “I listen for ticking clocks. I can hear them through walls.”

“When does she not come home?”

“I hear them everywhere — in the walls, down the street.”

She covered her face with her hands in a small, violent motion and held them there a moment. When she lowered them, her face was composed. “What are you afraid of?” she asked him.

“Nothing,” he said.

“You have to say something.”

“Let me think,” he said, for no one had ever asked him this before.

That night, Lenny could not sleep. He went to the kitchen at 2:00 am for a glass of milk; again, he heard the girl’s footsteps. He watched her walk lightly through the foyer again. He waited until she had left and then followed her through the silent house. Aurora padded across the cold tile until she reached one of his coat closets. She picked up some of the favorite pieces in his wardrobe — his Armani loafers, his Yves Saint Laurent gloves. She did this quickly, efficiently, plucking up items and dropping them. She picked out two shoes and a glove, and lightly, like a ghost, she ran back to her room.

He did not move. He wanted her to take everything.

He still had not figured out what he was most afraid of when, about a month later, she did not come to breakfast. He was surprised by her absence but thought she was just sleeping late. He called from work to check in.

“She has the flu,” said Rosita. “She’s sleeping. Children get sick.”

He found it difficult to concentrate on his work and came home early to see her. She was groggy with fever, but mostly she slept. Her fever was 105. The pediatrician told him to take the girl to the emergency room.

They were borne together on a stale, glaring current of fear. The children’s wing of the hospital was like a haunted house: babies screamed as nurses held them down to take blood from their arms, children were wheeled out from operations, tubes rising out of their mouths. The parents walked slowly, like ghouls, beside the gurneys rolling their children out of surgery.

Aurora was with him, and then she was in the pediatric intensive care unit. The flu had developed into myocarditis, an illness of the heart. The doctor brought the residents around to discuss Aurora’s condition, for it was so rare it had never happened in the hospital before. They stared at her with smug, glazed eyes. Lenny tried over and over to reach Charlene at the clinic, but finally an administrator got on line and said, primly, “She left. She ran away two days ago with another patient.”

“Ran away?” he said. “Why didn’t you call me?”

“We were waiting to see if she called us.” She paused. “We assume no responsibility once they leave the premises. There were mutterings about South America.”

“Find her,” he said, “Or I’m suing you for so much money your head will spin.”

“What do you propose we do, Mr. Weiss? Send our counselors to South America? She wasn’t ready. We can’t force her. We’ll let you know if she contacts us.”

During his life, he had commanded budgets of millions of dollars, negotiated with businessmen on every continent on the globe. Now he had to act as Aurora’s guardian, and he stumbled wildly across the hospital linoleum. He tried to make sure Aurora would get good care from the nurses by offering them spots on his show. “We’re having a special episode. Pot of $500,000. You’d have a one-in-three chance.” Standing at the large, smoky windows of the waiting area, he gazed at the cars moving down the freeways. Closing his eyes, he tried to will them to go backward, to change the course of this day and the next, but they pressed ahead, silver backs flashing.

When Aurora had stabilized a week later, the doctor called him into his office. The office was filled with diplomas and drab orange chairs. Lenny perched on the edge of the chair while the doctor read the chart that Aurora’s pediatrician had sent him. “She was in Thailand two years ago,” he said.

“Her mother took her there.”

The doctor read the name of a disease Lenny did not know.

“She wasn’t treated properly. You shouldn’t drag children around on these treks to developing countries. Her heart suffered some damage then. This flu did more harm.”

Lenny remembered a postcard Charlene had sent from Bangkok:

Having a super time. Aurora loves curry. River rafting next week.

He closed his eyes.

“Well, there’s no good way to put this,” said the doctor. “She needs a new heart.”

Lenny could not breathe. A sharp pain went through him, immense and shocking because its source was wholly emotional.

“We’ll put her on the transplant list,” the doctor said.

“List?”

“She has to wait.”

He had not waited on any list for over thirty years. Lenny stood up. His hair was uncombed and his face gray with exhaustion, but he felt the large, powerful weight of his body in his expensive suit. “What’s your job here, doctor?”

“I am the head of pediatric cardiology.” He was a slight man; his hair was thin. His eyelashes were feminine and curling. His desk glimmered with crystal paperweights.

Lenny put his hands on the man’s desk. “What do you need in your wing?”

“Pardon me?”

“Let me tell you how I see the new wing of the hospital,” said Lenny, glancing at the doctor’s nametag. “The Alfred A. Johnson wing. Twenty million dollars. A children’s playroom. Top equipment. A research lab. Endowed chairs.” He listened to the hoarse, meaty sound of his voice. “I am the producer of Anything for Money. Look at me.”

The hospital sent Aurora home. She was weak but did not know how ill she was, and Lenny did not tell her. He did not allow himself to think about her physical state. Instead, he indulged in feelings of pride at his wealth and its ability to bend the rules. When he received the letter from the hospital a few days later, he almost wanted to frame it, for it seemed to reflect some magnificence in his soul. The letter said: Aurora Weiss is number one on the list for transplants of the heart.

Lenny called the doctor once, twice a day. He awaited the ghoulish harvest reports: a young boy killed in a car accident, a teen stabbed to death in a fight. But none of these hearts had the right antigens that would match Aurora’s; they had to wait for the correct heart.

Waiting was what fools did; he decided to take things into his own hands. He stayed up all night, making calls. He spoke into a phone that did automatic translating to doctors in Germany, Sweden, France. His price soared. Thirty million dollars. New wings. Top equipment. Huge salaries. High-tech playrooms. He shouted these offers into the phone at 2:00 am, floating on the imagined gratitude of others. They would all talk about how Lenny Weiss had saved his granddaughter by calling every doctor in the world.

Aurora came into the room one night when Lenny was making his calls. She stood in her pajamas, staring, as he shouted into the phone.

“What’s wrong?” she asked.

He put down the phone.

He told her that her heart was not well and, in more detail, how he was going to help her. “I’m going to find one,” he said. “People know me and they want to help — ”

She saw through this immediately.

“I’m sorry!” she cried out. “Sorry, sorry — ”

He saw, at once, how his daughter had behaved as a mother.

“Aurora. I’ll save you,” he said; the sound of these words comforted him. “I swear it.”

But she did not let him touch her — she backed away from him with a dim expression. She was already disappearing and believed this was what people had truly wanted from her all along.

He skipped work. He did not sleep. The right heart was not appearing. He tried to think about who would give up their heart for millions of dollars. Drug addicts, the terminally ill — but their hearts would be in poor shape. He sat behind the dark glass of his limo, grimly watching girls play soccer, wishing one of them would trip. He imagined his Mercedes plowing into a group of teenage boys running on the sidewalk, killing enough of them to give Aurora more of a chance.

He proposed to his staff a special episode: “Who Will Die For Money.” They would audition people willing to give up their hearts for a staggering pot of $5 million. His staff thought it was a PR stunt and called an audition. The holding room filled with an assortment of the homeless, individuals not in the best health, and well-dressed, shifty types who seemed to think there was some way to obtain the money without dying.

They were all busily filling out their names and addresses when he got a call from Rosita.

“A heart has arrived on the doorstep,” she said.

He rushed home.

A man identified himself as a cardiac surgeon and a purveyor of black-market hearts. He was from Ukraine. Dr. Stoly Michavcezek sat in Lenny’s living room, holding a Styrofoam ice chest on his lap.

“Whose heart was this?” asked Lenny.

“A man. Olympic gymnast. Fell on mat and dead. Few hours. Payment up front.”

They transferred the heart, quickly, to Lenny’s enormous Sub-Zero freezer; then Lenny brought in a specialist from Cedars-Sinai to look at the heart.

“This isn’t a human heart,” said the doctor. “This is the heart of a chimp.”

When he returned to the studio, the prospective contestants had all been dismissed, and black-suited men from the legal department were waiting in his office.

“Lenny,” said one. “This has got to stop.”

Aurora worked on her movie obsessively; she spent much of her time in her room. When they had a meal together, he did most of the talking; he lied about his closeness to saving her. “There’s a doctor in Mexico,” he’d say, “a small hospital. International laws, they’re all we have to get around…” She ate very little and watched him like a child who had disbelieved adults her whole life.

One night, she burst out of her room and hurried to her seat at the table. “My plot has changed,” she said. “Listen. There are seventeen aliens from the planet of Eyahoo. They have legs in the shape of wheels and heads like potatoes. Their planet is very slippery, and they move very fast on their wheels. Often they bump into each other. Their heads are getting sore.”

He listened.

“They need a new cousin who can make their planet less slippery. Their cousin is named Yabonda, and she lives on a neighboring planet. She has long legs with huge feet that are very absorbent, like paper towels. They want to learn how to have feet like her. Now. Do you think they should maybe invite her to Eyahoo for dinner or just come and kidnap her?”

She leaned back in her chair, clasped her hands tightly, and watched him.

“What would happen with each?” he asked.

“If they asked her to dinner, she would be transported in a glamorous carriage made of starlight.”

“Uh-huh.”

“If they kidnapped her, it would hurt.” She stretched out her fingers, as though trying to hold everything. “Tell me,” she said, sharply.

When Aurora had learned about her condition, she stopped stealing. Lenny began leaving things out for her — his cell phone and toothbrush and car keys — in the hope that she would take them, but in the morning, they remained where he had left them. He missed her midnight rambling through the mansion, waking up to see which objects of his she would find precious.

One night, he heard her footsteps padding down the hall.

Lenny jumped out of bed and followed her. This time, Aurora seemed to have no particular direction, but went around the foyer like a floating, circling bird. Then she saw Lenny. They stared at each other in the dusk of the hallway, and the shocked quiet around them made Lenny feel that they were meeting for the first time.

Aurora began to cry. “I don’t know what to take.”

The girl knelt to the floor and threw up. The child’s distress made Lenny feel as though he himself were dissolving.

“Take me,” said Lenny.

The girl stared at him.

“I’ll go with you,” said Lenny.

“Where?”

“Wherever. I’ll go too.”

“How?”

“I can find a way to do it.”

He did not know how to stop these words, did not know if they were lies or the truth — they simply came out of him.

“I don’t want to be by myself,” said Aurora.

He closed his eyes and said, “I’ll be there, too.”

When the dawn came, he was sleeping on the floor beside Aurora’s bed. He woke up, his promise an inchoate, cold feeling in his body; then he remembered what he had said.

He got up quietly and left the room.

It was just six in the morning. Lenny went to his garage and got into his red Ferrari convertible. He shot up the Pacific Coast Highway, feeling the engine’s force vibrate through his body. The highway stretched, a ribbon reaching through the blue haze to the rest of the world. He felt poisoned by the girl’s presence in himself and wanted to get her out.

By eight o’clock, he had hit Santa Barbara. The main street was filled with a clear golden light, and the people strolling the sidewalks looked so contented and purposeful he wished they were all dead. He thought of the way Aurora stood on half-toe when she wanted something, the sweet, terrible optimism in the girl’s walk when she headed down the hallway. He wanted to stop his car and rush out among the strangers and find a woman, proposition her, and have sex with her in an alley. He wanted to strip naked and run into the ocean. He wanted to drive his car into the glass windows of a restaurant and be put in jail. He drove back and forth down the main street for a while, hands trembling on the steering wheel.

He turned the car and roared toward where people knew him best: the studio. At 11:00 am, he walked through the doors and stood in the shadows, watching. Eight contestants were white-lit, hitting buzzers, shouting out answers to questions, and the producers and crew were scrambling noisily in the dark around the stage.

Lenny stared at the brilliant stage set. On this stage, he had seen parents allow their children to walk them on a leash, like dogs, for five hundred bucks. He had seen teens who agreed to twerk in front of their grandparents for a thousand. He had stood in this brightness, watching others fall dimly around him.

“Lenny,” he heard. “Hey, Lenny — ”

Now he stood in this corridor, a strange, familiar fear in his mouth. He knew what would be unbearable.

He turned around several times before he saw the exit. Pushing the metal doors, he ran into the parking lot, jumped into his car, and drove home.

When the Ferrari drove up to the mansion, Aurora was sitting on the stairs. The girl was still, as though she had been sitting there for a hundred years. Her blue eyes were fixed on Lenny as he began to walk up the stairs.

“I thought you weren’t coming back,” said Aurora.

“I had to do an errand,” said Lenny.

He sat beside Aurora on the stair.

“I have a new plot idea,” she said. “To help Yabonda.”

“What do you mean?”

“Her paper towel feet have dried out,” she said. “Whenever she lifts her feet, they make a weird crackling sound. Everyone on the planet wants her to go away. They can’t stand the noise her feet make. It keeps them all awake. There is mayhem and murder.” She looked right at him; her gaze was stern. “She meets Glungluck, a kindly alien who was kicked off her planet because her ears, which resemble long straws, suck up everything around them, and people were losing their purses and keys.”

“Go on,” he said.

“They make a neighborhood,” she said. “They add other sad aliens, Kogo and Zarooom. They build big walls around their neighborhood made of glass roses. The only aliens who can move in are other losers. They all have had bad luck. In their neighborhood, they can talk to each other. They make up songs and have contests. Nobody wins. When the good-luck aliens try to see through the wall of roses, they are jealous and lonely.”

He looked at her face. Her forehead was gray and creased, like an old person’s.

“I’ll produce,” he said.

He did not stop looking. He had kept the audition slips of the people who had been willing to give up their hearts for $5 million and was meeting one, Wayne Olden, secretly, for lunch at a Fatburger in Hollywood to check him out. He was planning to take him in for a full medical exam; after that he would hand over the organ donation forms. Lenny had not figured out how he would kill the man, particularly to maintain the integrity of his organs. They were finishing up a hot dog when he received a call.

“I’m not feeling good,” said Aurora.

“What’s wrong?”

“I don’t know.”

Lenny jumped up.

“I have to go,” he said to the man.

“You’re kidding,” said the man.

“Here,” said Lenny, throwing him a thousand-dollar bill. “That’s for lunch.”

The man looked disappointed. “I thought I was going to get five million bucks!”

Lenny’s Mercedes raced home. It was late afternoon, the shadows long and dark across the grass. Aurora was sitting on the lawn by the pool. She had brought out the sack of stolen items and had set out everything that she had taken. There were pens, staplers, shoes, caps, some loose change, postcards, a spoon, a sock, paper clips, some crumpled Kleenex. The brown paper bags that held them were crumpled up, a pile of small paper balls. All of this surrounded her; the late sun made her face look gold.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

“I don’t have enough,” she said.

He sat down beside her. His throat was stiff, tense. He said, “Tell me about them.”

She looked at the many items spread out in front of her. She picked up an aluminum cupcake tin. “Sharon Eastman. Cook in the Ambassador Hotel in Chicago, asked me about my favorite foods and showed me how to make cupcakes with buttercream frosting. She made one for me with a rose on it, as I said I wanted one.”

She picked up a coat hanger and said, “This was Greg Mixon’s, who was the coat-check man at the Century 100 Restaurant in Miami, where we went every night for dinner for a month, and who let me sit and read in a corner in the coat closet and gave me a new button for my coat and said this coat hanger would hold it…”

He listened to her talk and talk, her words coming fast, as though she were in a rush to get everything out. She remembered so much that the others had said, as though she had stored each sentence up when she had been told it. She leaned softly against his shoulder, and he put his arm around her. He was aware of the way his hands fell open by his sides, the way they could hold absolutely nothing.

“Aurora,” he said. “Wait.”

She stopped. Her face was flushed.

“Give me something.”

“What?”

“Give me something of yours. I need it.”

“What thing?”

“Anything.”

“You want something of mine?” she whispered, surprised.

“Yes. Now.”

She shrugged and dug into her pocket. There she had a small piece of red velvet that she had used on her poster for Danger. She handed it to him.

“Here,” she said.

He took the scrap of velvet, closed his fingers around it.

She sat up very straight and looked right at him. Her gaze was sharp. He froze. His skin was as thin as silk. He wondered what she could see, what the light of her gaze detected. He was aware of the palm trees moving gently in the warm wind; he believed he had stopped breathing.

He waited.

Around them, the night sky pressed down like a lid, the stars faint nicks of light in the darkness.

She sat back down; she didn’t say anything. It was a flat, immense silence, and it frightened him. He didn’t know what she saw, and he never would. He sat, not knowing what to say.

She picked up a paper clip off the lawn. She cupped it protectively in her hand.

“This was from Jennifer Macon in Washington, D.C.,” she said. He listened as she told about the paper clip and the rose barrette and the jar of lip balm. She talked, her voice softly piercing the air. The city lit up, a bright, glimmering plain, below them as the sky drained from orange to blue to black. Together, they sat, looking into the dim green exuberance of the garden.