Interviews

Ben Philippe on Being the Black Friend

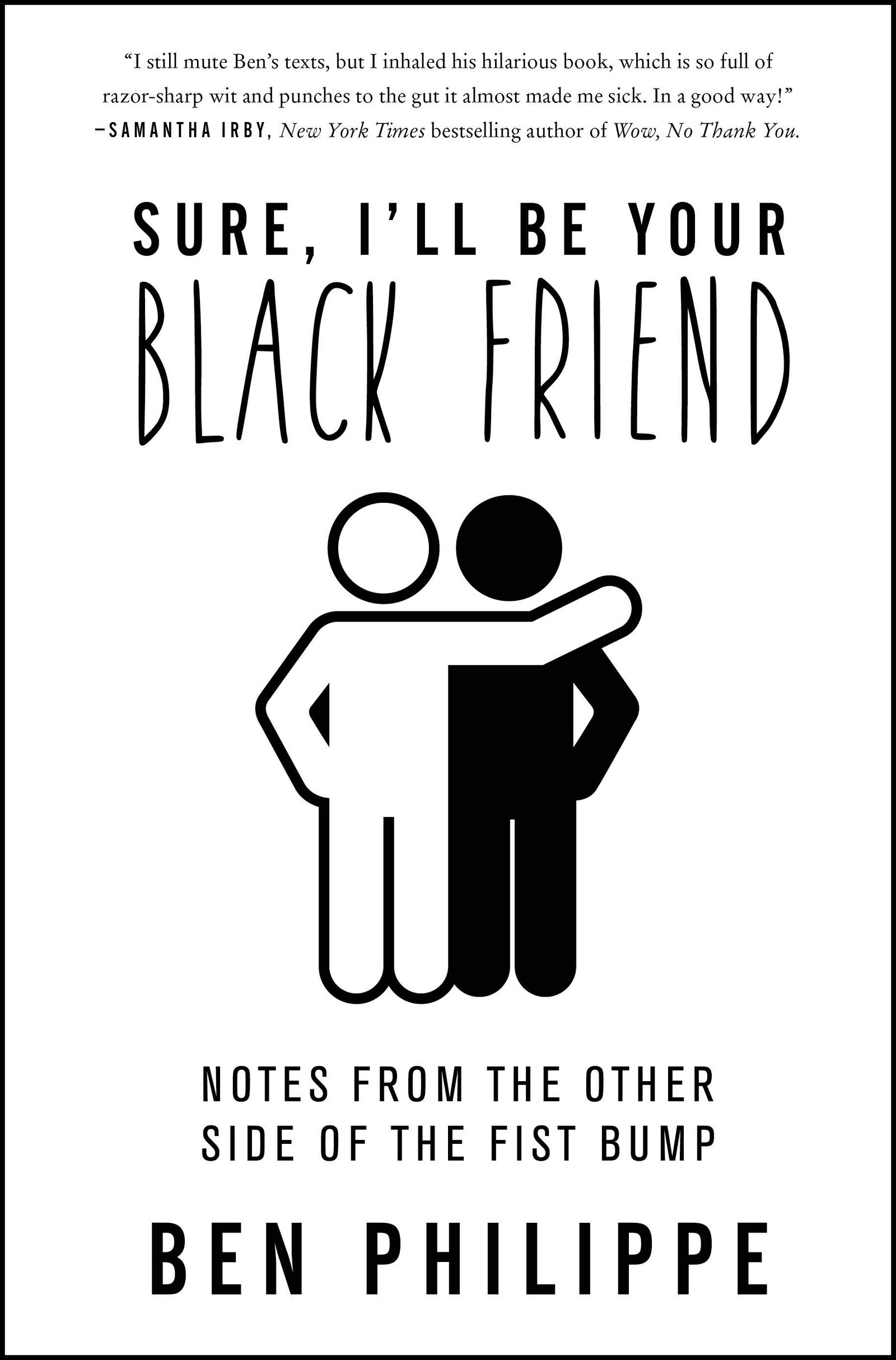

The author of “Sure, I’ll Be Your Black Friend” tells the story of his coming-of-age through the highs and lows of friendships

In the spring of 2020, Ben Philippe was in the middle of drafting a book on “the quirks and maybe the light trauma of having been the Black friend in white spaces” all his life. It was supposed to be a conversational, gently satirical take on the things white people should and shouldn’t do if they aspire to have a Black friend: Don’t touch the hair. Don’t ask if Black guys are bigger “down there.” Don’t say that you “just really don’t think about race” because you’ve never had to. Don’t claim white privilege isn’t a thing because the term “implies a boat full of Leonardo DiCaprio clones and a seven-digit bank account” and all you have is a stack of unpaid bills and a backache.

And then last summer happened. As if the coronavirus pandemic weren’t enough, Black people kept dying at the hands of police and the pattern stood out to the world in a new way: Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd. If 2019 was the Hot Girl Summer, thanks to an eponymous song by rapper Megan Thee Stallion, 2020 became the summer of Black Lives Matter.

Ben describes the experience as “a software update being added to my Blackness in real time.” It’s a transformation that comes through viscerally in the final essays of his new book, Sure, I’ll Be Your Black Friend: Notes from the Other Side of the First Bump.

Having known Ben for almost a decade and enjoyed his two young adult novels, The Field Guide to the North American Teenager and Charming as a Verb, I couldn’t wait to take the plunge. What I discovered was a book—part literary memoir, part study guide, and part sardonic etiquette primer—as deep, probing, humane, and, yes, funny, as the man himself.

Ben was born in Haiti and raised in Montreal, Canada, where he was often the only Black kid at school. He grew up speaking French at home and learned English by watching shows like Gilmore Girls on the WB (he still can’t go the length of one interview without mentioning the show. See below. I did not bring it up. He did!). Eventually, he moved to New York to go to Columbia, and then to Austin, Texas to attend the Michener Center for Writers, where we met.

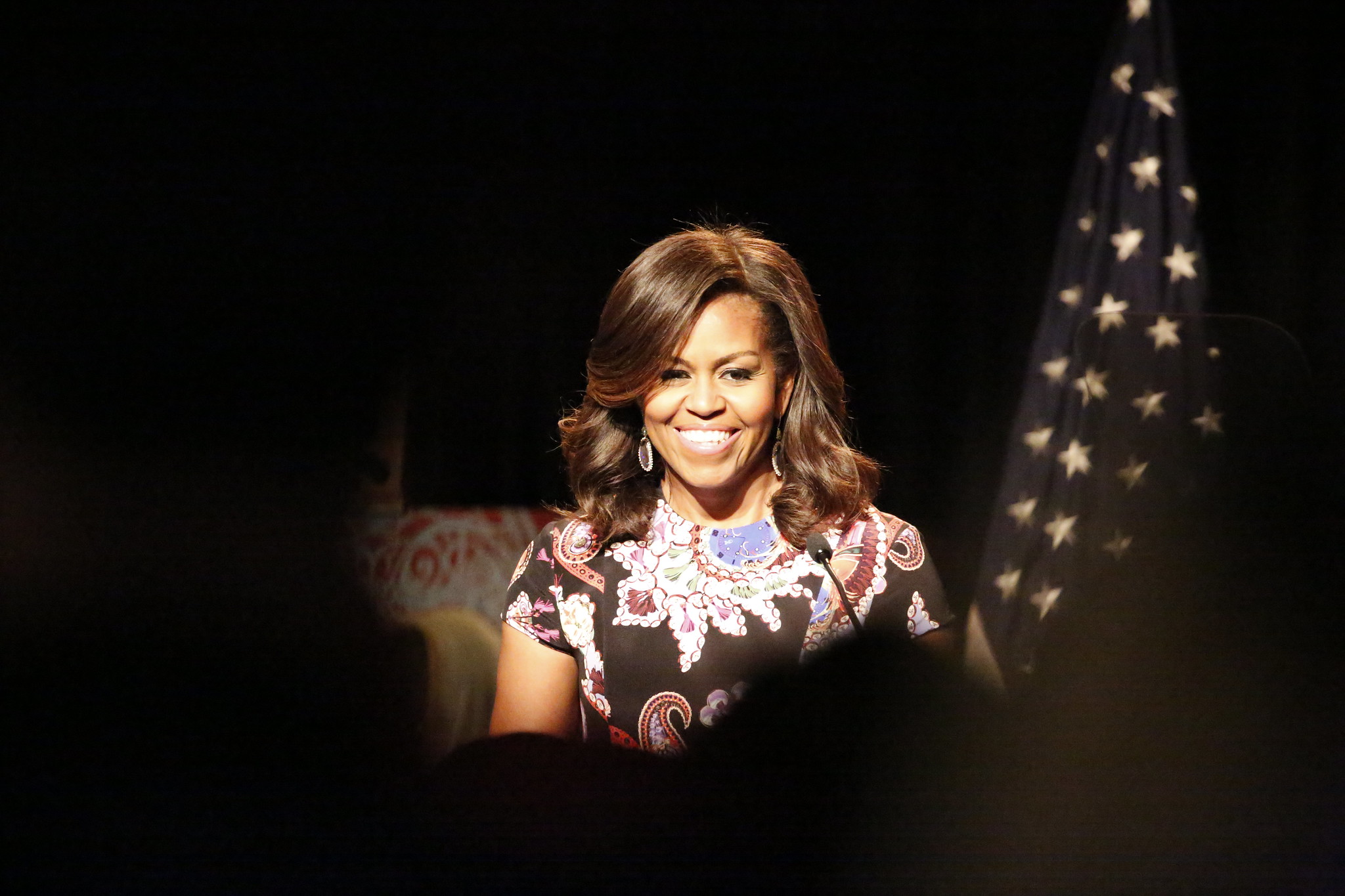

I talked with Ben—one of the warmest and wittiest people I know, with the wholesome good looks of a Disney Channel kid—over email about the beauty of friendship when you’re young, being Black in three countries, and coming out the other end of the Trump era.

Greg Marshall: Why do you think friendships in our youth are so formative?

Ben Philippe: It sometimes feels like the number of people we can say “I love you” to gets smaller as we get older. Your partner, your immediate family, your kids. There’s something sad about that to me. In elementary school, your best friend being seated 20 feet from you felt like a canyon! I used to use my friend’s deodorant stick on road trips. In college, my best friend would just sleep in my unmade bed. Now, friends get hotel rooms when they visit and we have dinner together, talk about mortgage rates. It’s part of growing up and I don’t need to use another 32-year-old man’s deodorant, but there’s also something sad about that distance to me. Something was lost there. I think that’s why adult friendships are no longer sacrosanct spaces that allow for political discourse and fraught conversations. They’re not magic anymore, lame as that is to say.

My friend has a line that I love and that I wish I could have shoehorned into the book: “Anyone who thinks you’re friendly is probably not your actual friend, Ben.” My few friends are the first barrier to all my, err, for lack of a better word, bullshit. The rage, the whininess, the moodiness, the insecurity, the dark memes…there’s an intimacy that comes with that. I love reflecting on that.

GM: Why were you interested in explicitly addressing white readers? What are you hoping they take from the book?

It sometimes feels like the number of people we can say ‘I love you’ to gets smaller as we get older.

BP: I did want the reader to think of me as a friend. I tried to artificially create that comfort level on the page, starting with blunt questions you might ask a Black friend who you know will not hold them against you—and then said Black friend goes on 20-page tangents about his childhood here and there because he’s kind of a narcissist.

Friendships are uneven constructs. You talk about heavy politics one moment, about pop culture the next, about your bad dates the moment after, and your friend might just angrily vent at you about the state of the world. Sometimes, you simply throw book recommendations at each other. I wanted the book to hit a few of those notes all at once.

I think coating everything I wanted to say in the highs and lows of a friendship made it easier to write without pretending to know more than I do. I have no grand thesis about the diaspora of Black America or the Haitian-Canadian-American migration narrative, just my thoughts as your Black friend Ben.

GM: Did writing about your life make you see it differently?

BP: Well, life doesn’t always have a satisfactory resolution. It’s a life lesson I had to learn; narrative closure is a lie taught to us by [beloved Michener instructors] Jim Magnuson and Elizabeth McCracken. If you’re very lucky, life just kind of goes on. You keep waiting for the dust to settle—work, romance, friendship, family, racial discourse, politics—but then you realize the unsettled dust is just life happening… I got that last line from an X-Men comic! Boom!

GM: You have some incredible Black women in your life, starting with your mom, Belzie. In the essay “Sister, Sister,” you reckon with your male privilege. Was that a tough thing to do?

BP: I need to stop writing about my mom. She Googles herself now. I’ve created a monster.

Honestly, I don’t think anyone likes to “wrestle with their privilege” or even interrogate it. It doesn’t feel good! So you can’t “tsk-tsk” white people for their privilege if you’re not willing to at least acknowledge your own. I’ve had plenty. The one I’ll never shake off is male privilege.

You can’t ‘tsk-tsk’ white people for their privilege if you’re not willing to at least acknowledge your own.

The essays where I gripe about my love life felt like the setup to a punchline where you widen the shot to reveal a row of exhausted Black women side-eyeing me, and wondering if this fool is serious. (That might still happen.) I’ve had enough Black women in my life to at least glimpse this massive chasm and it felt wrong not to at least mention it.

GM: 2020 was one hell of a year. What has writing about that journey been like for you?

BP: Groan. Exhausting! I’m sure a pithier version of the book would exist if the summer of 2020 didn’t happen in the middle of my writing it. It was overwhelming in a lot of ways. For a while there, I was just looking to burn bridges, ha. On paper, via email, in person. I wanted to yell at someone. Anyone! Like, please, tell me you’re calling the cops on me, Amy Cooper, watch me emotionally eviscerate you into a puddle.

But while anger is fun to ride (and write), it’s not very productive beyond the immediate catharsis. It’s kind of like putting any underlying thought in bold+underline+italics. It just covers the content you’re trying to get across. I couldn’t write an Angry Book—it would desiccate me—but I did manage to write a book with a couple of angry chapters in it.

GM: You describe the book as a “tell-some, not a tell-all.” In this book where so much about your life is on the table, what were some of the things you wouldn’t write about?

BP: Hmm. My current relationship. My last conversation with my dad. Trying to make it as a screenwriter. (I’m not coy about it; it just felt like a massive tangent.) Some racist encounters that were just kind of boring. Some bridges were too dull to even bother burning. How terrified I am that this, writing as a career with a credit score of three digits, is all going to go away in the blink of an eye. Snakes.

GM: What’s your take on social media as a writer? We should note that you are verified on Twitter, you bastard.

BP: That blue checkmark both means nothing and people are despondent when it goes away, ha. I probably would be too, to be honest. But I at least try to remember that it’s all just 1s and 0s in our phone and not to take it too seriously? My followers count also plateaued at around 6K, so luckily the publisher never puts too much weight into it when they buy one of my books. This guy ain’t no influencer, thank God.

I don’t think social media has changed my writing habits too much beyond the absolute cringe of mandatory self-promotion. I block liberally; I only engage if I feel like it; I tell Ted Cruz he sucks regularly. It’s all about striking that healthy balance.

I remember making a joke about Rory Gilmore from Gilmore Girls being a literal bastard once and a very nice mom replied something like, “What does this say to the single parents of your readers?” I blocked her right away. Like, no. I’m not getting into a serious exchange about this because you process jokes from the great internet abyss as commentary on your life, Helen. You live inside my phone; I don’t live inside yours.

GM: I know a lot of the book was written during the Trump era. Are you feeling more optimistic now that we have Biden in office?

BP: I am! I am feeling more optimistic with Biden in office than Trump. It feels like the least controversial statement in the world but people get mad about that sentiment, too!

“The Democrats suck, too!” “Now’s not the time to get complacent!” It’s like going “Hurray! My arm isn’t on active fire anymore!” and having someone answer, “Ok, but have you even checked your cholesterol lately?”