Lit Mags

Cathay

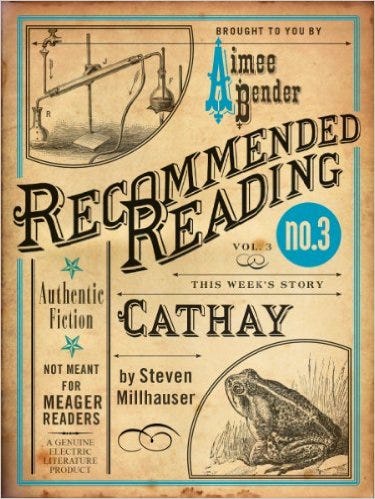

by Steven Millhauser, recommended by Aimee Bender

EDITOR’S NOTE by Aimee Bender

In one of my favorite Hans Christian Andersen stories, “The Nightingale,” the Emperor of China falls in love with the songs of nightingale but he is soon distracted by the gift of an amazing mechanical bird, sent to him by the Emperor of Japan. The story (currently smartly collected in a tiny anthology called Fairy Tales for Computers because it really is about technology) becomes a way to talk about the very human tug between the natural and the artificial.

Millhauser starts his gorgeous “Cathay” with 12 singing birds, which are just like birds except for their golden bodies; that we know they are gold only increases our wonder. “Cathay” — an alternate name for China — takes up where “The Nightingale” left off, almost exactly 140 years earlier. His is a made-up land, a love letter to art, a capsule of loneliness, a painting of beauty that makes me catch my breath from the care and skill of the writer/painter who is adorning each paragraph with filigrees of language while also dipping us over and over again into all that empty white space.

The story first strikes with its beauty. When I read it for the first time (small spoiler alert), I was enraptured by those painted eyelids. First, the delicacy of the image, and then the perfect progression to the more private canvas of the areola. From one level of elegant seduction to another. And maybe that’s a microcosm of the story’s skillfulness right there — these mini-paintings appear to be just image, just beauty, but a subtle movement takes place and storytelling kicks in. Something shifts when a careful blink across a room leads to the discovery one lover makes of another when clothes come off in a secluded chamber.

I’ve taught this story many times, often as a way into talking about permission and what a story can do. The allure of the chunk paragraphs, each one as carefully tended as a Japanese garden. The marvelous hilarity of those dwarfs! The way he crafts a sentence, like a graceful curious watchmaker. The Borgesian mysteries in each room. (When listening to Borges stories on audiotape this past spring, I was struck by the lineage there, too, how Millhauser seems a certain descendant.) Millhauser is always deeply musical and precise with his phrasings, so every sentence is a pleasure, but this story is not simply a pretty list, an accounting of a place. By the end, through the mystery and sadness packed inside the images, the story asks us complicated questions about art and wonder. What do we need more? The world, or its reflection? The known, or the imaginative? And how about that ending scene?

And when the Emperor walks those Corridors of Insomnia, corridors “so long that a man galloping on horseback would fail to reach the end of either in the space of a night,” it’s so stunningly exact in its mystery. Millhauser nails down something elusive about what it’s like to be awake all night, as the whole story nails down something fleeting about who we are, and how we live. We need our metaphors to survive, he reminds us, and perhaps we can find our way to transcendence through artifice. These questions seem ever more relevant in our current world, thirty years after the story was published, which happened before internet, and virtual realities, and the big birth of our computer selves.

This is a story that uplifts, and saddens, and bewilders, and shimmers.

Nothing quite like it.

Aimee Bender

Cathay

Steven Milhauser

Share article

BIRDS

THE TWELVE SINGING BIRDS in the throne room of the Imperial Palace are made of beaten gold, except for the throats, which are of silver, and the eyes, which are of transparent emerald-green jade. The leaves of the great tree in which they sit are of copper, and the trunk and branches of opaque jade, the whole painted to imitate the natural colors of leaf, stem, and bark. When they sit on the branches, among the thick foliage, the birds are visible as only a glint of gold or flash of jade, although their sublime song is readily heard from every quarter of the throne room, and even in the outer hall. The birds do not always remain in the leaves, but now and then rise from their branches and fly about the tree. Sometimes one settles on the shoulder of the Emperor and pours into his ear the notes of its melodious and melancholy song. It is known that the tones are produced by an inner mechanism containing a minute crystalline pin, but the secret of its construction remains well guarded. The series of motions performed by the mechanical birds is of necessity repetitive, but the art is so skillful that one is never aware of recurrence, and indeed only by concentrating one’s attention ruthlessly upon the motions of a single bird is one able, after a time, to discover at what point the series begins again, for the motions of all twelve birds are different and have been cleverly devised to draw attention away from any one of them. The shape and motions of the birds are so lifelike that they might easily be mistaken for real birds were it not for their golden forms, and many believe that it was to avoid such a mistake, and to increase our wonder, that the birds were permitted in this manner alone to retain the appearance of artifice.

CLOUDS

The clouds of Cathay are of an unusual purity of whiteness, and distinguish themselves clearly against the rich lapis lazuli of our skies. Perhaps for this reason we have been able to classify our cloud-shapes with a precision and thoroughness unknown to other lands. It may safely be said that no cloud in our heavens can assume a shape which has not already been named. The name is always of an object, natural or artificial, that exists in our empire, which is so vast that it is said to contain all things. Thus a cloud may be Wave Number One, or Wave Number Six Hundred Sixty-two, or Dragon’s Tail Number Seven, or Wind-in-Wheat Number Forty-five, or Imperial Saddle Number Twenty-three. The result of our completeness is that our clouds lack the vagueness and indecision that sadden other skies, and are forbidden randomness except in the order of appearance of images. It is as if they are a fluid form of sculpture, arranging themselves at will into a succession of imitations. The artistry of our skies, for one well trained in the catalogues of shape, does not cause monotony by banishing the unknown; rather, it fills us with joyful surprise, as if, tossing into the air a handful of sand, one should see it assume, in quick succession, the shape of dragon, hourglass, stirrup, palace, swan.

THE CORRIDORS OF INSOMNIA

When the Emperor cannot sleep, he leaves his chamber and walks in either of two private corridors, which have been designed for this purpose and have become known as the Corridors of Insomnia. The corridors are so long that a man galloping on horseback would fail to reach the end of either in the space of a night. One corridor has walls of jade polished to the brightness of mirrors. The floor is covered with a scarlet carpet and the corridor is brightly lit by the fires of many chandeliers. In the jade mirrors, divided by vertical bands of gold, the Emperor can see himself endlessly reflected in depth after depth of dark green, while in the distance the perfectly straight walls appear to come to a point. The second corridor is dark, rough, and winding. The walls have been fashioned to resemble the walls of a cave, and the distance between them is highly irregular; sometimes they come so close together that the Emperor can barely force his way through, while at other times they are twice the distance apart of the jade walls of the straight corridor. This corridor is lit by sputtering torches that leave long spaces of blackness. The floor is earthen and littered with stones; an occasional dark puddle reflects a torch.

HOURGLASSES

The art of the hourglass is highly developed in Cathay. White sand and red sand are most common, but sands of all colors are widely used, although many prefer snow-water or quicksilver. The glass containers assume a lavish variety of forms; the monkey hourglasses of our northeast provinces are justly renowned. Exquisite erotic hourglasses, often draped in translucent silks, are seen in the home of every nobleman. Our Emperor has a passion for hourglasses; aside from his private collection there are innumerable hourglasses throughout the vast reaches of the Imperial Palace, including the gardens and parks, so that the Turner of Hourglasses and his many assistants are continually busy. It is said that the Emperor carries with him, sewn into his robe, a tiny golden hourglass, fashioned by one of the court miniaturists. It is said that if you stand in any of the myriad halls, chambers, and corridors of the Imperial Palace, and listen intently in the silence of the night, you can hear the faint and neverending sound of sand sifting through hourglasses.

CONCUBINES

The Emperor’s concubines live in secluded but splendid apartments in the northwest wing, where the mechanicians and miniaturists are also lodged. The proximity is not fanciful, for the concubines are honored as artificers. The walk of a concubine is a masterpiece of lubricity in comparison to which the tumultuous motions of an ordinary woman carried to rapture by the act of love are a formal expression of polite interest in a boring conversation. For an ordinary mortal to witness the walk of a concubine, even accidentally and through a distant lattice-window, is for him to experience a destructive ecstasy far in excess of the intensest pleasures he has known. These unfortunate courtiers, broken by a glance, pass the remainder of their lives in a feverish torment of unsatisfied longing. The concubines, some of whom are as young as fourteen, are said to wear four transparent silk robes, of scarlet, rose-yellow, white, and plum, respectively. What we know of their art comes to us by way of the eunuchs, who enjoy their privileged position and are not always to be trusted. That art appears to depend in large part upon the erotic paradoxes of transparent concealment and opaque revelation. Mirrors, silks, the dark velvet of rugs and coverlets, transparent blue pools in the concealed courtyard, scarves and sashes, veils, scarlet and jade light through colored glass, shadows, implications, illusions, duplicities of disclosure, a profound understanding of monotony and surprise — such are the tools of the concubines’ art. Although they live in the palace, they have about them an insubstantiality, an air of legend, for they are never seen except by the Emperor, who is divine, by the attendant eunuchs, who are not real men, and by such courtiers as are half mad with tormented longing and cannot explain what they have seen. It has been said that the concubines do not exist; the jest contains a deep truth, for like all artists they live so profoundly in illusion that gradually their lives grow illusory. It is not too much to say that these high representatives of the flesh, these lavish expressions of desire, live entirely in spirit; they are abstract as scholars; they are our only virgins.

BOREDOM

Our boredom, like our zest, can only be as great as our lives. How much greater and more terrible, then, must be the boredom of our Emperor, which flows into every corridor of the palace, spills into the parks and gardens, stretches to the utmost edges of our unimaginably vast empire, and, still not exhausted, but perhaps even strengthened by such exercise, rises to the height of heaven itself.

DWARFS

The Emperor has two dwarfs, both of whom are disliked by the court, although for different reasons. One dwarf is dark, humpbacked, and coarse-featured, with long unruly hair. This dwarf mocks the Emperor, imitates his gestures in a disrespectful way, contradicts his opinions, and in general plays the buffoon. Sometimes he runs among the Court Ladies, brushing against them as he passes, and even, to the horror of everyone, lifting their robes and concealing himself beneath them. Nothing is more disturbing than to see a beautiful Court Lady standing with this impudent lump beneath her robe. The ladies are nevertheless forced to endure such indignities, for the Emperor has given his dwarf freedoms which no one else receives. The other dwarf is neat, aloof, and severe in feature and dress. The Emperor often discusses with him questions of philosophy, art, and warfare. This dwarf detests the dark dwarf, whom he once wounded gravely in a duel; so far as possible they avoid each other. Far from approving of the dark dwarf’s rival, we are intensely jealous of his intimacy with the Emperor. If one were to ask us which dwarf is more pleasing, our unhesitating answer would be: We want them both dead.

EYELIDS

The art of illuminating the eyelid is old and honorable, and no Court Lady is without her miniaturist. These delicate and precise paintings, in black, white, red, green, and blue ink, are highly prized by our courtiers, and especially by lovers, who read in them profound and ambiguous messages. One can never be certain, when one sees a handsome courtier gazing passionately into the eyes of a beautiful lady, whether he is searching for the soul behind her eyes or whether he is striving to attain a glimpse of her elegant and dangerous eyelids. These paintings are never the same, and indeed are different for each eyelid, and one cannot know, gazing across the room at a beautiful lady with whom one has not yet become intimate, whether her lowered eyelids will reveal a tall willow with dripping branches; an arched bridge in snow; a pear blossom and hummingbird; a crane among cocks; rice leaves bending in the wind; a wall with open gate, through which can be seen a distant village on a hillside. When speaking, a Court Lady will lower her eyelids many times, offering tantalizing glimpses of little scenes that seem to express the elusive mystery of her soul. The lover well knows that these eyelid miniatures, at once public and intimate, half-exposed and always hiding, allude to the secret miniatures of the hidden eyes, or the eyes of the breast. These miniature masterpieces are inked upon the rosy areola surrounding the nipple and sometimes upon the sides and tip of the nipple itself. A lover disrobing his mistress in the first ecstasy of her consent is so eager for his sight of those secret miniatures that sometimes he lingers too long in rapturous contemplation and thereby incurs severe displeasure. Some Court Ladies delight in erotic miniatures of the most startling kind, and it is impossible to express the troubled excitement with which a lover, stirred to exaltation by the elegant turn of a cheekbone and the shy purity of a glance, discovers upon the breast of his beloved an exquisitely inked scene of riot and debauchery.

DRAGONS

The dragons of Cathay dwell in caves in the mountains of the north and in the depths of the Eastern Sea. The dragons rarely show themselves, but we are always aware of them, for their motions are responsible for storms at sea, great waves, hurricanes, tornadoes, and earthquakes. A sea dragon rising from the waves can sink an entire fleet with one lash of its terrible tail. Sometimes a northern dragon will leave its cave and fly through the air, covering whole cities with its immense shadow. Those who have stood in the shadow of the dragon say it is accompanied by an icy wind. The tail of a dragon, glittering in the light of the sun, is said to be covered with blue and yellow scales. The head of a dragon is emerald and gold, its tongue scarlet, its eyes pits of fire. It is said that the venom which drips from its terrible jaws is hotter than boiling pitch. It is said that to see a dragon is to be changed forever. Some do not believe in dragons, because they have not seen them; it is like not believing in one’s own death, because one has not yet died.

MINIATURES

Our passion for the miniature is by no means exhausted by the painting of eyelids; the art of carving in miniature is one of the oldest and most esteemed of our arts. Well known is the Emperor’s miniature palace, which sits upon a jade cabinet beside the tree with the twelve singing birds, and which is said to reproduce with absolute fidelity the vast Imperial Palace, with its thousands of chambers and corridors, as well as its innumerable courtyards, parks, and gardens. Within the miniature palace, which is no larger than a small table, one can see, by means of a magnifying lens, myriad pieces of precise furniture, as well as entire sets of cups, bowls, and dishes, and even a pair of scissors so tiny that when fully opened they can be concealed behind the leg of a fly. In the miniature throne room one can see a minute jade table with a miniature palace, and it is said that within this second palace, which can scarcely be seen by the naked eye, the artist has again reproduced the entire Imperial Palace.

SUMMER NIGHTS

On a summer night, when the moon is a white blossom in a blue garden, it is good to go out of the palace and walk in the Garden of Islands. The arched wooden bridges over their perfect reflections, the hanging willows, the white swans over the swans in the dark water, the yellow and blue lights in the palace, the smell of plum blossoms, all these speak of peace and harmony, and quell the rebellious restlessness of the soul. If, on such a night, one happens to see a dark green frog leap into the water, sending out a rainbow of ripples that make the moon waver, one’s happiness is complete.

UGLY WOMEN

It is well known that the Court Ladies are the loveliest in the empire, but among them one always sees several who can only be called ugly. We are not speaking of ladies who are grotesque, monstrous, or unclean, but merely of ladies who are strikingly unpleasing to our eyes. Instead of thin, arched eyebrows they have thick, straight eyebrows, which sometimes grow together; one or more of their teeth may be noticeably crooked; their noses and mouths are too large, their eyes too wide apart or close together. Since no one can remain at the palace without the consent of the Emperor, it is clear that he considers their presence inoffensive, and perhaps even desirable. Indeed, to the embarrassment of the court, he has sometimes chosen an ugly lady for his mistress. It is a mystery that teases the understanding, for to say that the Emperor is an admirer of beauty is to speak with misleading coolness. Our Emperor reveres beauty, lives and breathes in a world of beautiful objects, lavishes wealth and honor on the creators of beauty, is, despite his terrible omnipotence, entirely submissive to the beauty of a teacup, a plum blossom, a white cheek. The Empress is renowned for her delicate loveliness. How is it, then, that our Emperor can bear to have ugly women in his court, and appears even to encourage their presence? It is easy of course to imagine that he sometimes grows weary of the exquisitely beautiful women who meet his gaze wherever he turns. In the same way our Court Poets are advised to introduce occasional small dullnesses and imperfections into their verses, in order to relieve the hearer from the monotony of perfection. One can even go further, and grant that the beauty of our ladies has about it a high, noble, and spiritual quality that lifts it above the realm of the merely physical. But ugliness, by its very nature, draws attention to the physical. One might imagine, then, that the Emperor longs to escape from the spiritual beauty of our Court Ladies and to abandon himself to the physical pleasures which seem to be promised by the ugly ladies — as if the coarseness and impropriety of their faces were an intimation or revelation of dark, coarse, improper pleasures hidden beneath their elegant silks. Yet it is difficult to see how this can be the true explanation, since the Emperor’s longing for sensual pleasure may always be satisfied by his incomparable concubines. Another explanation remains. It is known that the Emperor is an admirer of beauty; there is no reason to assume that in this instance he has changed. Is it not possible that the Emperor sees in these ugly women a beauty to which we, with our smaller understanding, are hopelessly blind? Our poets have said that there can be no beauty without strangeness. One imagines our Emperor returning to his chamber from the stimulation of his concubines. From those unimaginably desirable women, those masterpieces of the art of appearance, who express in every feature of face and body the physical loveliness he has craved, he is returning to a world of Court Ladies, themselves flowers of beauty who in some turn of the lip, some glance, some look of sweet pensiveness may even surpass the wholly sensual beauty of his concubines. As he passes through the corridors leading to the east wing, he comes upon a lady and her maids. The lady has thick, straight eyebrows that nearly grow together; her nose is broad; she gives a clumsy curtsey. The ugly eyebrows, the broad nose, the clumsy gestures irritate his dulled senses into attention, and many days later, when he has passed long hours among his concubines and lovely ladies, he will suddenly recall, with a burst of excitement, those thick eyebrows, that broad nose, that clumsy curtsey, for like a beautiful woman suddenly glimpsed behind a lattice-window she will lead his soul away from the torpor of the familiar into a dark realm of strangeness and wonder.

ISLANDS

The floating islands of Cathay are most commonly found in our lakes, especially the great southern lakes, but they occur in our rivers as well. Nothing is more delightful, for a group of Court Ladies walking by a pleasant riverside, than to see one of these islands floating by. The younger ladies, little more than girls, laugh and cry out, and even older and more sober women can scarcely suppress their joy. It is quite different when these same ladies are in a boat on the water, for then the island, whose motions are entirely unpredictable, is an object of great terror. Except for their motion, these islands are like ordinary islands, and the question of their origin has never been answered. Our ancient historians classified floating islands with water-animals, but we are less certain. Some believe that floating islands are a special race of islands, which reproduce and which have no relation whatever to common islands. Others believe that floating islands are common islands that have broken away; animated by boredom, melancholy, and restlessness, they follow no certain path, bringing with them the joy of surprise and the pain of the unknown.

MIRRORS

The ladies of Cathay, and above all the Court Ladies, have for their mirrors a passion so intense that a lover feels he can never inspire such ardors of uninterrupted attention. The mirror of a lady holds her with its powerful and irresistible gaze, desires her to be wholly his, and in the privacy of the night encourages disrobings. What torture for the yearning and neglected lover to imagine his lady at night in her chamber, alone with her amorous mirror. He imagines the mirror’s passionate and hungry gaze, which holds her spellbound; the long, searching look, deep into her treacherous eyes; her slow surrender to the act of reflection. The mirror, having drawn the lady into his silver depths, begins to yearn for still greater intimacies. Once in the glass, she begins to feel an inner tickling; she feels about to swoon; her eyes, half-closed, have a veiled and drowsy look; and all at once, yielding to her mirror’s imperious need, she slips from her robe, and boldly gives her nakedness to the glass. And perhaps, when she turns her back to her mirror, in preparation for peering slyly over her shoulder, for a moment she hesitates, permitting herself to be seen and savored by the insatiable glass, feeling her skin tingle in that stern, lecherous, unsparing gaze. Is it surprising that her lover, meeting her the next morning, sees that she is pale and somewhat tired, not yet recovered from the excesses of the night?

YEARNING

There are Fifty-four Steps of Love, of which the fifth is Yearning. There are seventeen degrees of Yearning, through all of which the lover must pass before reaching the sixth step, which is Restlessness.

THE PALACE

The palace of the Emperor is so vast that a man cannot pass through all its chambers in a lifetime. Whole portions of the palace are neglected and abandoned, and begin to lead a strange, independent existence. It is told how the Emperor, riding alone one day in one of the southeastern gardens, dismounted and entered a wing of the palace through an open window. He had never seen the chambers of this wing before; their decorations had for him an inexpressible and faintly troubling charm. Coming upon an old man, dressed in old-fashioned ceremonial robes, he asked a question; the man replied in an accent which the Emperor had never heard. In time the Emperor discovered that the inhabitants of this wing were descendants of the Emperor’s great-grandfather; living for four generations in this unfrequented part of the palace, they had kept to the old ways, and the old pronunciation. Shaken, the Emperor rode away, and in the ensuing nights paid many visits to his concubines.

BLUE HORSES

The Emperor’s blue horses in a field of white snow.

SORROW

The Twelve Images of Sorrow are: the autumn moon behind three black branches, a mirror when it does not reflect a face, a single white plum-petal hanging from a bough, the eyes of a beautiful lady at dusk, a garden in summer rain, frosty breath on an autumn night, an old man gazing at a river, a faded fan, a dead sparrow in the snow, a lover leaving his mistress at dawn, an old abandoned hourglass, the black form of the wild duck against the red setting sun. These are the sorrows known to all men, but there is a sorrow that is only of Cathay. Our sorrow is the sorrow hidden in the depths of rich, deep-blue summer afternoons, the sorrow of sunshine on the blossoming plum tree, the sorrow that lies like a faint purple shadow in the iris of a beautiful, laughing girl.

THE MAN IN A MAZE

It sometimes happens that a child’s toy, newly invented by one of the sublime toymakers of Cathay, enchants our Emperor. The toy is at once taken up by his courtiers, and for days or weeks or even months at a time the entire court is in a fever over that toy, which suddenly drops into disfavor and soon passes out of existence altogether. One such toy that took the fancy of the Emperor was a small closed ivory box, of a size easily held in the hand. The inside of the box was composed of many partitions, forming a maze. The partitions were invisible but were shown by black lines on the outside of the box. The tiny, invisible ball, which was of gold, was called The Man in a Maze. One would often see the Emperor standing alone by a window, his head bowed gravely over the little toy that he held in the palm of his hand.

BARBARIANS

Often there is talk of the barbarians who press upon us at the outermost limits of the empire. Although our armies are invincible, our fortifications impregnable, our mountains impassable, and our forests impenetrable, our women shudder and look about with uneasy eyes. Sometimes a forbidden thought comes: to be a barbarian, to sit upon a black horse with flaming nostrils and hooves of thunder, to ride swifter than fire with one’s long hair streaming in the wind.

THE CONTEST OF MAGICIANS

In the shimmering and legendary past of Cathay, when history and fable were often confounded, an Emperor is said to have held a contest of magicians. From all four quarters of the empire the magicians flocked to the Imperial Palace, to perform in the throne room and seek to be chosen as Court Magician. In those days the art of magic was taken far more seriously than it is today, and scarcely a boy in the empire but could turn a peach blossom into a dove. The Emperor, seated high on his throne in the presence of his most powerful courtiers and his most beautiful Court Ladies, permitted each magician only a single trick, after which the magician was informed, by means of a folded note brought to him on a silver tray outside the doors of the throne room, whether he was to depart or stay. Those chosen to remain were lodged in elegant chambers, and later were asked to perform a second time before the Emperor, although on this occasion the performance took place in the presence of two rival magicians. Since two of the three magicians were destined to be dismissed, there was a strong air of drama about this stage of the contest, and it is said that the magicians continually sought to bribe the courtiers and Court Ladies, all of whom, however, remained incorruptible. Some magicians wished to be the first of the three to perform, others longed to be second, and still others believed that the advantage lay with him who was third, and many arguments raged on all three sides of the question — quite in vain, since the order was decided by lot, the rice leaves being drawn by the Empress herself. The one hundred twenty-eight magicians remaining after this stage of the battle were now requested to perform in pairs; and in this manner the magicians were gradually reduced to sixty-four, and to thirty-two, and to sixteen, and to eight, and to four, and at last to only two. When there were only two magicians left, one of whom was a vigorous man of ripe years, and the other an old man with a white beard, there was a pause for one week, during which the court prepared for the final match, while the magicians were permitted to rest or practice, as they pleased. At last the great day came, the lots were drawn, and the younger man was chosen to perform first. He had astonished everyone with the daring and elegance of his earlier performances, and a hush came over the court as he climbed the carpeted steps of the handsome ebony and ivory platform constructed for the magicians by the Emperor’s own carpenter. The magician bowed, and announced that he had a request. He asked a member of the court to bring to him, there on his platform, the statue of a beautiful woman. He himself would gladly bring a jade or marble statue out of the ends of his fingers; but he asked for a statue to be brought to him so that there could be no question concerning the true nature of the statue. This unusual request produced murmurs of uncertainty, but at last it was decided to humor his whim; and six strong courtiers were dispatched to fetch from the Emperor’s collection the statue of a beautiful woman. It was promptly done; and the beautiful jade statue stood upon the ebony and ivory platform. The magician moved his hands before the stone woman, and as the court watched in awe, the statue slowly began to wake. The jade body turned to flesh, the jade lips to red lips, the jade hair to shiny black hair; and a beautiful living girl stood on the platform, looking about in bewilderment. The magician at once robed her, and led her forth among the astonished court; she spoke, and laughed, and in every way was a real, live girl. So awestruck were the courtiers, who had never seen any trick like it before, that they almost forgot the second magician, who sat to one side and waited. After a while the attention of the court returned to the neglected magician, about whom they were now curious, for no one could imagine a more brilliant trick than the godlike deed of breathing life into inanimate matter. The old magician, who was by no means feeble, took his place on the platform, and to the surprise of all present he praised his rival, saying that in all his years of devotion to the noble art of magic he had seen nothing to equal such a deed. For certainly it was wonderful to bring life out of stone, just as in the ancient fables. He hoped, too, that a woman of such high beauty would not frown upon the praises of an old magician. At this the newly created woman smiled, and looked all the more beautiful. The old magician then bowed, and said that he too had a request: he would like the six courtiers to bring him the statue of a beautiful woman. The court was surprised at the old magician’s request, for even if he had mastered the art of bringing forth a live woman from the stone, his deed could only equal that of his rival, without surpassing it; and by virtue of being second, he would seem only an imitator, without daring or originality. Meanwhile the six courtiers fetched a second jade statue, and placed it upon the ebony and ivory platform. In beauty the second statue rivaled the first, and young courtiers crowded close to the platform, eagerly awaiting her transformation. The old magician waved his hands before the stone, and slowly it began to wake. The jade arms moved, the jade lips parted, the jade eyes blinked and looked about; and a beautiful jade girl stood on the platform, smiling and crossing her smooth jade arms. The magician led her forth among the marveling courtiers, who reached out to touch her green arms and her green hair; and some said her arms were jade, yet warm, and some said her arms were flesh, but stony cold. All crowded around her, staring and wondering; and the old magician led her up to the Emperor. His Imperial Majesty said that although there were many beautiful women in his court, there was but one breathing statue; and without hesitation he awarded the prize to the old magician. It is said that the first woman grew ill-tempered at the attention showered upon her rival, and that the first task of the new Court Magician was to change her back into a beautiful statue.

End

Author’s Bio

Steven Millhauser is the author of twelve works of fiction, including the story collections Dangerous Laughter and The Knife Thrower. His most recent book is We Others: New and Selected Stories.