Books & Culture

Corporate Censorship Is a Serious, and Mostly Invisible, Threat to Publishing

When states suppress ideas, we condemn it. What should we do when companies do the same?

With some 687 million books sold in the U.S. in 2017, book-selling has been on the rise since taking a dive following the 2008 recession. Still, there’s the odd politician, religious group, or police institution eager to advance an agenda by labeling a particular book persona non grata — or, since it’s a book, “liber non grata.” In recent months, South Carolina’s Charleston County Fraternal Order of Police vowed to “put a stop” to the sentiment behind Angie Thomas’s young adult novel The Hate U Give, urging the book’s banning from a summer reading list; the story follows a black teenage girl who takes up activism after a white police officer pulls over the car she rides in and brutally murders her childhood friend in front of her. In November 2017 the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue in New York City demanded that an independent bookstore chain “publicly rescind their support for P Is for Palestine,” an alphabet children’s book highlighting Palestinian culture and liberation under Israeli occupation. Earlier that year Arkansas Rep. Ken Hendren proposed an ultimately defeated state legislature bill banning all writings by radical historian Howard Zinn’s published between 1959–2010.

Invariably civil libertarians jump to the fray to condemn such measures, rightly, as censorship, like when the New Jersey ACLU challenged the state’s prison system on its decision to restrict Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow from reaching prisoners’ hands, leading to the ban’s reversal in January 2018. Ironically in many cases, the censor’s intended goal has the opposite effect, because book sales often increase under the threat of a ban, as happened in the Zinn-Hendren case and others throughout history. Mark Twain, always his own shrewd publicist, was thrilled when the Concord Public Library banned The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn weeks after publication, thanking them for the “generous action” that “doubled its sale” and swelled readership.

When state or civil authorities blacklist books, the act is correctly labeled censorship. But what is the word when parent corporations act out political or ideological dissatisfaction by ordering their subsidiaries to snuff out information in the form of books, magazines, newspapers, radio, television, movies? There isn’t a word or phrase that fully captures this form of censorship, at least not a negative phrase.

When state or civil authorities blacklist books, the act is correctly labeled censorship. But what is the word when corporations order their subsidiaries to snuff out information?

On the other hand, it’s not hard to call to mind examples of civil or government censorship, all perceived nefariously. Like me, you might think first of all the states that notoriously organized public book burnings — from Nazi Germany to South Africa. Next are the states throughout the world that continually ban books to try and stop offensive ideas from taking root in people’s minds. In the U.S., this type of censorship is closer to home. For example, the Tucson, Arizona public school district tried to terminate its astonishingly successful Mexican American studies program, which looked at history and art through the viewpoint of Mexican American contributions, on the basis that it encouraged “ethnic solidarity.” (This is the actual phrase written into state law Arizona Revised Statutes 15–112 — “Prohibited courses and classes,” under the subcategory of “enforcement.”) I’ve written elsewhere about how the “cultural genocide” committed by Arizona’s statewide ban on a partly Maya-based Mexican American studies (also Nahuatl-based) in high schools relates to the U.S.-backed physical “acts of genocide,” as defined by the U.N., against Mayan groups in Guatemala in the early 1980s. These state-directed book bannings and burnings are thankfully near universally condemned, with some exception such as when the same Tucson district successfully banned Middle East Studies in 1983 under false anti-Israel bias allegations. In January 2018, a federal judge issued a permanent injunction against the Arizona law that banned Mexican American Studies from ever being enforced again.

But many times book censorship still succeeds without a whimper. This kind of censorship is largely disregarded and often tacitly tolerated and self-induced among editors: corporate censorship. On the surface, there’s a logic in corporate censorship that may seem at least arguable. When corporate executives at, say, Netflix cancel your favorite shoot-em-up action show or a boy-meets-boy love story, seemingly without cause, there’s a knee-jerk feeling of dissatisfaction that eventually gives way to complacency. Just as corporate executives giveth us the stories we like, so can corporate executives taketh them away. They can do what they want; it’s their property.

But not so fast.

Is it — or should it be — a universal right for corporations to censor their so-called property in all cases, under all circumstances? One case from the 1970s may command some second thoughts on a corporate safe zone cordoned off by copyright laws and cultural misconceptions, one that calls into question the entire endeavor of corporate censorship.

Writing Behind My Country’s Back

Two social critics and media analysts, Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman, wrote several books together. Their first book about U.S. state and media representation of global massacres, Counter-Revolutionary Violence: Bloodbaths in Fact & Propaganda, was, in 1973, set to publish by an academic publisher, Warner Modular Publications, then a subsidiary of Warner Communications (now WarnerMedia). Former Washington Post managing editor Ben Bagdikian’s 1983 book The Media Monopoly covers the scandalous affair that ensued from Warner Modular’s attempted publication of the Chomsky-Herman book that brought about the publisher’s fatal downfall. An enterprising journalist, Bagdikian was the messenger of the 1971 Pentagon Papers leak by former military analyst Daniel Ellsberg that spurred public outrage over the secret, expanded war effort in Southeast Asia as well as the fact that the government had known for years that the war was unwinnable while costing thousands of U.S. soldier deaths alongside millions of Vietnamese, Laotians, Cambodians, and others.

The literary conflagration began to smolder in August 1973 when a Warner executive, the company’s chief of book operations William Sarnoff, glanced at an advance mock-up advertisement for the Chomsky-Herman book set to splash across the Nation, the New Republic, New York Times, New York Review of Books, and Saturday Review. Alarm bells went off in Sarnoff’s mind as he imagined more government leaks that would embarrass President Nixon and, by association, the Warner parent company. Given that Warner’s corporate officers had contributed to Nixon’s 1972 presidential bid and the aptly acronymed Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP), Sarnoff was surely on edge about anything that could trigger more political incendiary under Nixon, then under intense media, congressional, and legal scrutiny over the Watergate corruption scandal. In May, the Nixon administration had lost its aggressive pursuit of Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers leaker, whom Nixon’s national security advisor Henry Kissinger called “the most dangerous man in America.” Now, the Chomsky-Herman book’s provocative title and marketing was enough to spur Sarnoff’s fears of another government leak that could embarrass the company.

Sarnoff phoned the publisher of Warner Modular in Andover, Massachusetts, Claude McCaleb, demanding an explanation. McCaleb tried to assuage his boss’s concern by clarifying that the book was not at all a document leak. The title merely carried critical analysis by two academic professionals — from the Wharton School of Finance and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology — of publicly available material. Two hours later, Sarnoff called again, ordering McCaleb to New York immediately to hand-deliver him copy of the book to his Rockefeller Plaza office. McCaleb dropped off a copy of the book in the morning and headed to an academic convention where more advance copies of the book were to arrive. At the convention booth, he received word from Sarnoff: “Report at once.” McCaleb could only wonder what was in store for him once he arrived, which nineteen years in academic publishing didn’t prepare him for.

Macmillan to President: No, You Actually Can’t Suppress Books You Don’t Like

Bagdikian, who died in 2016, boldly took on corporate censorship first-hand from his experiences working in the belly of the beast of corporate monopolists; he named the cabal, collectively, the “new Private Ministry of Information and Culture,” a riff on George Orwell’s sci-fi dystopian novel 1984. “A corporation dependent on public opinion and government policy,” Bagdikian writes, “can call upon its media subsidiaries to help in what the media are clearly able to do — influence public opinion and government policy.” And while it’s not always necessary or possible for media subsidiaries to benefit their parent company’s public image, they can at least refrain from publicly criticizing them, which is the line of orthodoxy that guided William Sarnoff in his quest against the publication of Counter-Revolutionary Violence.

It didn’t matter to Sarnoff that, not 20 years prior, co-author Noam Chomsky’s theory of Universal Grammar turned 2,000 years of scientific understanding about human language on its head. Or that Chomsky would go on to rank on the Arts & Humanities Citation Index as the highest-cited (living) source on earth next to Shakespeare, the Bible, Freud, Karl Marx, Cicero, and others. Such accomplishments are no match for a corporation’s public image perceived to be at stake.

As soon as McCaleb stepped into Sarnoff’s corporate office after being summoned from the convention hall, Sarnoff flew into a rage. McCaleb patiently reminded Sarnoff of the agreement they made when he and his staff were hired: Warner Modular enjoys discretion to publish the titles they choose, and their sales would reflect their success or failure. It’s unclear whether Sarnoff read the copy of Counter-Revolutionary Violence that McCaleb delivered when he berated the book as “a pack of lies, a scurrilous attack on respected Americans” and an “undocumented” book “unworthy of a serious publisher.” Despite the defamation charges Sarnoff levied, he agreed with McCaleb that the book was not libelous. Sarnoff veered to other complaints that Warner Modular published too many left-wing writers. McCaleb pointed out that his catalog included right-wing writers like Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek.

Sarnoff responded to McCaleb’s overall line of reasoning not with concessions or further discussion of possible compromise but, instead, by canceling all the ads for the book and the entire first print run, which had already begun coming off the press.

But destroying the book wasn’t enough. Sarnoff shut down Warner Modular completely, annihilating the publisher as an institution and all the books in its catalog, in order to prevent this one book from being published.

Sarnoff annihilated the publisher as an institution and all the books in its catalog, in order to prevent this one book from being published.

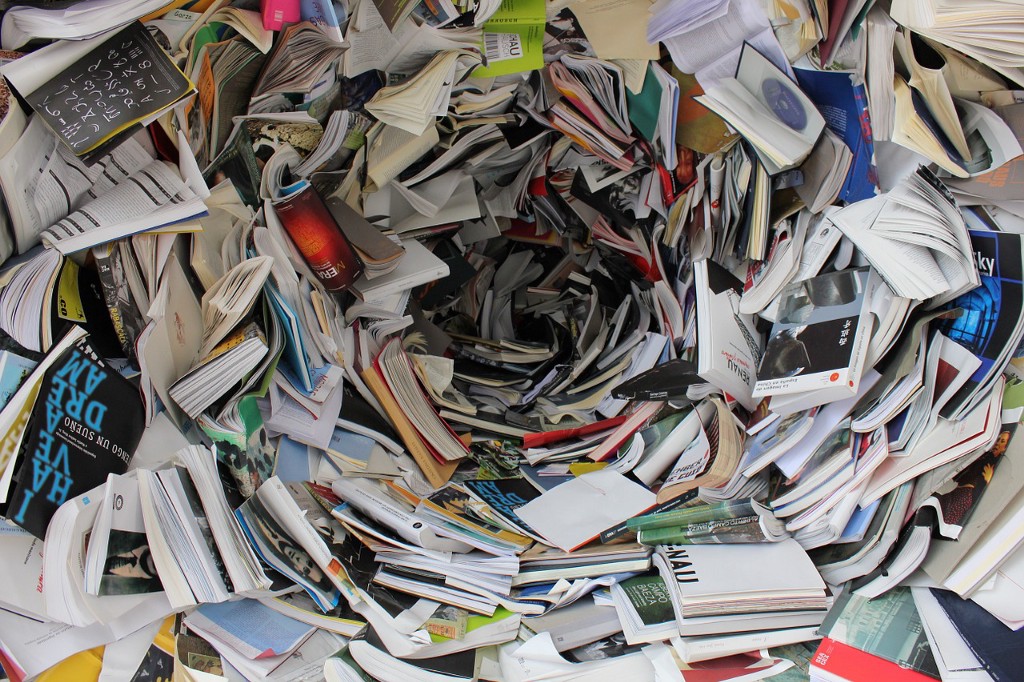

And the fate of the books themselves, the 10,000-volume print run that had started? The books were all “pulped” — literally liquidated by tossing the books into “the hogger” that swallows and digests books whole, turning them into a milky cellulose substance that is remolded into clean paper. In a way, pulping books is more effective than burning them, since books are like bricks and require a lot of overhead to destroy them completely.

Ideas, by their nature, do not seem containable. But in the curious Warner Modular case of corporate censorship, they were. Imagining the demise into liquid pulp matter, I think of the ending scenes of James Cameron’s action classic Terminator 2: Judgement Day when the fearsome T-1000’s seemingly unbreakable poly-alloy body dies screaming and thrashing in an industrial melting pot of liquid fire before disintegrating quietly into a bright, burning saffron eternity. To this day, Counter-Revolutionary Violence is out of print and largely unknown.

This past October I met Chomsky in his cozy, well-lit University of Arizona office at the end of a long, dim, narrow hallway with exposed piping running along the ceiling. All these years later, Chomsky looks at the Warner Modular episode with a fresh sense of derision — as if it was just yesterday that Sarnoff secured the publisher’s undoing with one fell slam of his phone. “It was interesting that virtually no civil libertarian thought there was any problem with [destroying Warner Modular to stop the book from being published] because it’s not state censorship,” Chomsky said. “It’s just corporate censorship.”

The fate of Counter-Revolutionary Violence is not an exceptional statistical error but the reigning rule of thumb among owning-class corporations. Filmmaker Michael Moore, while at work on his celebrated 1989 documentary, Roger & Me, about General Motors’ destruction of Flint, Michigan, reviewed several cases of corporate censorship, each as outrageous as the Warner Modular affair. The examples describe the bitter ruination that follows when books, as paper-bound bundles of ideas, conflict with business interests and get sent to the hogger under all the crushing weight that corporate executives, and the culture that precedes them, can apply.

When the first edition of The Media Monopoly hit bookstores in 1983, some 50 corporations dominated the scene, and the biggest merger at that time was $340 million. Bagdikian put the social math this way: “The 50 men and women who head these corporations would fit in a large room.” Yet by each book edition that followed every few years, the number shrank nimbly as corporations merged and concentrated themselves among few owner hands but stretched their power and influence across an ever-expanding blob of subsidiary companies. By 1990, in time for Bagdikian’s third edition of the book, 23 companies reigned over the industry. Today, all of six firms control the media scene where the biggest merger to date, AOL Time Warner, was $350 billion — 1000 percent higher than what media owners in 1983 could manage to do.

This isn’t to suggest a media conspiracy among corporate parents and subsidiaries all headed by the William Sarnoffs of the world that control, by force if necessary, every editor’s move. “Instead,” Bagdikian writes, “there is something more insidious: a system of shared values within contemporary American corporate culture and corporations’ power to extend that culture to the American people, inappropriate as it may be.” That culture creates a system that is at least as effectively governed as the rule of force, or even of official censorship, if not more canny.

Bagdikian eloquently describes what’s at stake here. “Americans, like most people, get images of the world from their newspapers, magazines, radio, television, books, and movies. The mass media become the authority at any given moment for what is true and what is false, what is reality and what is fantasy, what is important and what is trivial. There is no greater force in shaping the public mind; even brute force triumphs only by creating an accepting attitude toward the brutes.”

For Bagdikian, who feared more than corporate profits and domination, “the gravest loss is in the self-serving censorship of political and social ideas.” In truth, the occasions of official censorship by executives like Sarnoff are rare and “most of the screening is subtle, some not even occurring at a conscious level,” Bagdikian writes, “as when subordinates learn by habit to conform to owners’ ideas.” Taking one area of media, he cites an American Society of Newspaper Editors survey, which found that 33 percent of editors admitted they wouldn’t publish criticism of their parent company.

In an American Society of Newspaper Editors survey, 33 percent of editors admitted they wouldn’t publish criticism of their parent company.

The phenomenon is also not unique to the United States. When George Orwell’s fancifully satirical novel Animal Farm was set to be published in England in 1946, his preface titled “The Freedom of the Press” discussed what drove his invention of the book, observing that the “sinister fact” about censorship in England “is that it is largely voluntary,” and adding: “Unpopular ideas can be silenced, and inconvenient facts kept dark, without the need for any official ban.” In the case of corporate censorship, “voluntary” almost seems a vulgarly mild, if not outlandishly inaccurate, term to describe the act of killing a book’s publication, not to speak of its entire publisher. Although Orwell’s main point regards the way self-censorship functions as “intellectual cowardice,” which is “the worst enemy a writer or journalist has to face,” later in the preface Orwell touches closer to the structural business interests that also governed one end of the publishing world in his country: “The British press is extremely centralized, and most of it is owned by wealthy men who have every motive to be dishonest on certain topics.”

In a twist of original “Orwellian” irony, Orwell’s preface itself remained suppressed for decades, down the “memory hole” he coined in 1984, until it was discovered posthumously among his papers, and proved his argument by ensuring that his ideas about reality, which served the basis for his fiction, wouldn’t be read by the public.

A woeful effect of the monopolist system and its free-censorship culture firmly in place is that official acts of corporate censorship are hard to track, and the prevalent cases of self-censorship are perhaps impossible to identify or prevent. And, to top it off, the encompassing shield of copyright law ultimately protects the censors as the legally untouchable owners and operators of censorship — so much so that the word itself appears as Orwellian “doublethink” where, thanks to effective indoctrination, two contrary beliefs are accepted at the same time. In other words, censorship clearly is at play when executives like Sarnoff blackout their McCaleb editor underlings before they might criticize the parent company, until the McCalebs learn to censor themselves so the Sarnoffs don’t have to. But simultaneously, none of it is really censorship in the end because all the conflicts occur within the corporate dominion that legally owns it. This at a time when corporations already enjoy far greater liberties than individuals. As Chomsky has pointed out elsewhere, so-called “free trade” agreements are really “investor rights agreements” because they can sue governments for loss of profits and move freely, unregulated, across borders, causing economic crisis for small farmers and workers in Mexico and Central America, when border industrial surveillance regimes are heavily built up to staunch people’s mobility.

Meanwhile, the more familiar cases of censorship by states and civil institutions are easier to grasp, so we focus on them. The result: an almost imperceptible politics of censorship emerges that blurs — indeed divides and separates — the lines between what we may call “worthy” and “unworthy” kinds of censorship. In a way, corporations wield the censorship that dares not say its name.

In a way, corporations wield the censorship that dares not say its name.

Media mergers and conglomeration accelerated under Reagan, and continued apace under Clinton through the present day. As corporate conglomeration has skyrocketed, the means and scope of corporate censorship have grown more powerful. Bagdikian foresaw the danger early on: “If a small number of publishers, all with the same special outlook, dominate the marketplace of public ideas, something vital is lost to an open society. In countries like the Soviet Union a state publishing house imposes a political test on what will be printed. If the same kind of control over public ideas is exercised by a private entrepreneur, the effect of a corporate line is not different from that of a party line.”

As media mergers have grown very rapidly over a single generation’s time, the power of Bagdikian’s observation has reached its direst point of caution today. Disregarding this history legitimizes the delusion that things have always been that way. Too often there is a one-sided conversation going on where corporate censorship subordinates state censorship as a kind of scapegoat or red herring while the business end of ideological control proceeds as usual, unchallenged. Until the same gut rejection of state censorship broadens to include its powerful corporate counterpart, the conversation on censorship remains limited, and ultimately unfinished.