interviews

Embracing the Worst Thing Someone Can Say to You

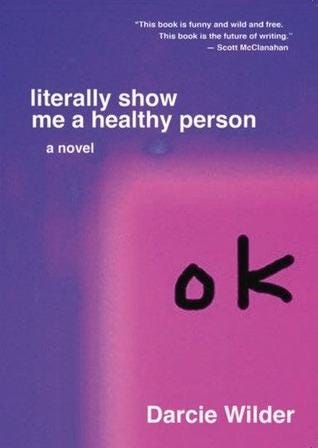

Darcie Wilder on death, samurai codes & making art out of Twitter

I would say that Darcie Wilder’s new novel, literally show me a healthy person (Tyrant Books, 2017), feels like it was sent from the future, one in which our collective hand-wringing over the significance of the internet and social media, or the dichotomy between high and low art, or of which artists’ stories we deem to be necessary has finally been resolved. But saying that would ignore how unbelievably of-the-moment this book is. It’s a book of grief and anxiety, of questions and confessions. One that explores the way pain and anxiety can be simultaneously public and private, constant but not always at the top of a person’s mind. A book that asks: what if the words we angrily (or drunkenly) tap out on our phones, that we save as notes, or send to ex lovers, or post publicly on social media, the ones we send without bothering to correct for typos, are the words we mean the most?

Halfway through, after noticing that my reading had idled, and that I had spent several minutes reading and reflecting on another of its many hypotheticals (in this case, would marriage exist without the concept of death), I emailed Wilder and asked if she would answer some questions I would share in a Google Doc. I sent the message, turned my attention back to her book, and was mortified by a question posed on the very next page: would you rather share a google doc or fuck without a condom.

Since then I have noticed how many lines from the novel have infected my brain and return to me unexpectedly as arguments in support of the part of my subconscious that constantly analyzes and re-analyzes my actions and the way I treat other people, the part of my brain that frames reality and processes it, that grieves and worries, the part that is writing the story of which I am both the villain and the hero.

Bryan Woods: Since I follow you on Twitter, I know a lot of the book is composed of fragments that first appeared online, but that knowledge didn’t really change how I read it. It seems like writers are still doing a lot of worrying about Twitter, but you’re using it almost like an interactive moleskine. Do you think there is a difference between what you write on the internet and your book in terms of artistic value?

Darcie Wilder: Cool, thank you. Yeah, I use it more like a notepad, but also very performative and definitely interactive with people online. The act of how an audience will be receiving a sentence or a paragraph, either on paper or while scrolling through a list of other people’s real-time sentences is definitely an aspect. But I also very much like revisiting lines that were written in that moment and seeing them untouched, like a scrapbook or a photograph.

Overall I think the internet is changing how artists and writers produce work, but the idea that you can’t use something because you’ve already posted a scrap of it online or because you were working on it publicly seems against my idea of art. There’s been repetition in art forever, and the piece of work often doesn’t come out finished and whole and ready to be absorbed by the audience. It’s a piece of art, not a spoiler.

In school we’d see cut after cut of a film before it was done, and I think tweeting is similar to that, but it’s also its own thing. There are some tweets that are legendary, but will still always only be a tweet, but then there are some that transcend that and work in a larger piece. I view them as different mediums and sometimes value one over the other, but it’s kind of always shifting. I think the real thing to worry about in regard to technology are the scary effects on our livelihoods and rights, not our artistic processes and social dynamics, which I think should evolve and embrace change, or at least be malleable. But there’s also a larger conversation about being online, content, and who profits.

BW: A lot of people are talking about aphorisms lately. Before reading your book I had just finished Sarah Manguso’s 300 Arguments, which is explicitly marketed as a collection of aphorisms, but literally show me a healthy person is brimming with them as well. One of my favorites: “people laugh if you say something serious in the tone of something funny. if you say something funny in the tone of something serious they block your phone number.” The main difference with the aphorisms you write is that they’re often framed in the passive voice or posed as a question. Do you think of these pieces as aphorisms?

DW: That’s interesting. No, I never thought of them that way but I don’t disagree. It reminds me of the ideas behind being allowed to speak with authority, who you’re allowed to speak for, and what you’re allowed to say is true for you. Which is relevant to anecdotes and memory and the past, which is a good chunk of the book. Like an intersection of relatability but not dictating anyone else’s experience. Like, I’d never set out to write a book of aphorisms, but they kind of came out by linking a lot of different observations and experiences that may or may not be relatable to different people. Also, a fear of mine is the reduction of thoughts, ideas, and feelings into these tiny sentences which is really limiting and destructive.

BW: The rhythm of the book floored me, and reminded me of the best standup routines I’ve seen. Not only because of the humor, but also because of the precise way you build these successive setups, each raising the stakes a little higher, only to tear it all down with a phrase that would make me lol or rip my heart out. Do you have a background in comedy?

DW: Thanks, I feel like most of the work was figuring out that rhythm and tone. I grew up on comedy and standup as a kid, watching hours of syndicated SNLs and half-hour specials. I have a bit of a background in comedy, but never really felt comfortable allowing myself to totally commit to it. But I also never fully allowed myself to leave it behind, or to stop being funny. I’ve always kind of felt caught in the middle between a serious, grief-stricken tone and self-aware humor. I like how those play together and the tension of them, plus it’s so similar to my coping mechanisms and tone of voice I have to use to get people to listen to me.

BW: I was struck by the way the manic, loose form of the book allowed certain themes to continually and naturally bubble up to the surface, sometimes after a trigger, but sometimes for no reason at all. I particularly found it heartbreaking the way the narrator’s grief over the loss of her mother, which is usually underlying but constant, and which is amplified by her father’s negligence, recurs in a way that feels so real. Did you set out to structure the book this way? Or did it emerge on its own?

DW: A bit of both. I had been writing these scraps of anecdotes since 2012 and didn’t know what to do with them. I began assembling them for a submission to my friend Sean’s zine Humor and the Abject, and that became the first six pages. Earlier drafts were split up into chapters and sections, but it became apparent to me that it needed to be one long unbroken thing. So it’s not stream-of-consciousness, but it’s not a conventionally structured narrative. I’ve always been interested in other types of narrative forms and experimental and experiential stuff, and I think it’s interesting to plot out the entire thing and sprinkle interspersed recurring themes and ideas but also see the ways they link back to each other in unplanned ways.

Not to use the words “magic,” “universe,” or “perfect,” but whenever I’m making something I think that the context it’s made in — like how it works with the time and place — pops up unintentionally like that. And although the book is a mixture of fiction and fact, those themes are true-to-life and because of that they can pop up in more organic and surprising ways.

Your brain is always working and connecting ideas, it’s like how tweets fall from the sky sometimes because you’re just thinking about things in the back of your mind, or thinking about a lot of things at once. I wrote that marriage/death tweet at 10 AM in a Monday morning meeting when my boss mentioned his wife and I immediately went to death. Similarly, the themes in this book are kind of like those unresolved moments you can’t stop going back to, and never get any better. The length of death is always the same. I can’t get over the length of forever, that you really will never hear a dead person’s voice again and sometimes that fact hits differently on a Monday morning versus 10pm at a bar versus 3am on the subway home.

“I can’t get over the length of forever, that you really will never hear a dead person’s voice again and sometimes that fact hits differently on a Monday morning versus 10pm at a bar versus 3am on the subway home.”

BW: Together the fragments form a clear narrative, but there are elements that make this book unique stylistically, like the ‘meaningful typos,’ if you know what I mean. What was the editing process like?

DW: I like preserving some sentences as they were when they were written, either in the moment or afterward, which is still in the moment of another feeling, which is different from any other moment when I’m looking back on it. So I find it really difficult to choose which aspects to preserve and which to change, and to go back between how it might be received and how it should be as a piece of work.

Some of the work was culling together a bunch of things I’d written over the past few years, and some was rereading and noting down other anecdotes and writing to link back to other themes, and a lot of it was rearranging sentences for when the specific reoccurring theme or idea would hit again, finding the ebb and flow, like a lyrical anecdote or piece of music.

The biggest edit was the last, which was changing the title to literally show me a healthy person instead of khdjysbfshfsjtstjsjts, which was the working title for two years and only changed for practical purposes. But I wanted that title so bad because it was so clearly manically just hitting keys on a keyboard but also reminiscent of that moment when you’re caught off guard and haven’t spoken yet and then blurt something out, but overall the most important part was it was super recognizable visually but completely unpronounceable. It also perfectly fit into that scrapbook idea of preservation.

From Suicide Hotlines to Taxidermy

BW: Changing the subject briefly, I’ve read a lot of books that deal with sex and literal shit, but I can’t think of another book that deals so frequently with vomit and cum, aside from Melissa Broder’s incredible essay “My Vomit Fetish, Myself” in So Sad Today. Are they just taboo? Was it difficult to handle these topics in a way that didn’t come across as tawdry? Why do these bodily functions and fluids have so much power on the page? Many lines, like “text me like i dont know how your cum tastes” are among my favorite, and I’m glad they made it into the book.

DW: I love that book and that essay. Yeah, I guess I do mention cum and vomit a lot. Both are pretty powerful and terrifying. I guess I’m kind of fascinated by vomiting because it’s both totally out of our control, our body takes over to expel it out, but that’s kind of comforting because it’s a reminder that our bodies make sense and can protect us. But it also terrifies me because it’s so out of our control because our body is taking over, and that actions intended to protect, or defense mechanisms, have their own problems.

I also didn’t vomit for like, ten or twelve years once and had to relearn how to vomit when I started drinking too much, and still pretty much have to instigate it if that’s what needs to happen. Sorry TMI. Also, vomiting is definitely most similar to my process because of the idea of tossing a bunch of themes and ideas together, seeing how they go down, then kind of figuring out what’s going on when it’s on the way back up. Plus, I spent so much of my life being scared to talk that I think there’s a link there.

Cum seems easier because it’s so dangerous depending on what happens with it. Also some people feel very uncomfortable hearing someone else — especially someone who can’t make their own or can get pregnant from it — talk about their cum. Unfortunately this can sometimes be all the power someone has in a relationship. I think I’m relieved that I talk a lot less about cum now since I finished writing this book.

“Some people feel very uncomfortable hearing someone else — especially someone who can’t make their own or can get pregnant from it — talk about their cum.”

BW: There’s a scene in a club where the DJ plays a song with the lyrics “I’m shinin’ on my ex, bitch.” I assume this is “My X” by Rae Sremmurd and not “X” by 21 Savage, which contains a similar line, as well as “[I] hit her with no condom, had to make her eat a Plan B.” There’s so much pop music that depicts events that take place in your book (the Plan B pill is a recurring motif), but told from the opposite perspective, by the men who have these experiences, who block women like your narrator from their phones, and who write hit songs with their buddies about having sex with her. I know you grew up listening to pop punk, which I think also often contains similar, if lighter, themes of ‘toxic masculinity.’ Do you see your book as a part of, or a response to, this kind of art?

DW: Definitely. It feels kind of like confronting your worst fears, or what used to be my worst fear as a teenager or a kid. Or actually maybe still is my worst fear — the worst thing a guy can say after you’ve had sex with them. Even when they don’t know they’re being fucked up to you, what can you do? It’s basically that Samurai idea that says there is freedom if you live as if you’re already dead, which I also mention in the book. It took me years and years to get to this mindset, and it’s kind of a “fuck it, who cares” thing. Although it’s not a total rejection of accountability, but instead is riffing and playing against the ways the male gaze and guys themselves can spin things. I don’t think there’s that much art from that perspective, which is a really vulnerable place to be. But embracing that turns into something that feels more powerful, maybe even weaponized. Also kind of like an act of redemption, embracing the worst thing someone can say to you.

BW: It’s interesting that the narrator seems to treat therapy and astrology more seriously than other ways she deals with pain. She doesn’t seem to expect any of them to solve her problems, but revelations from her therapist and horoscopes that say exactly what she wants to read (even if she has to scour the web to find the right one) are handled with warmth and significance, particularly when they’re enabling. This idea, of finding beauty and meaning in being enabled by others, struck me. Is that true or am I projecting?

DW: LOL. Exactly. I’m hesitant to call those things in the book “enabling,” but yes, beauty and love isn’t reserved for things that are perfect or what you want them to be.