essays

In the Dark and the Gloom: Alvin Schwartz’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark

by Matt Bell

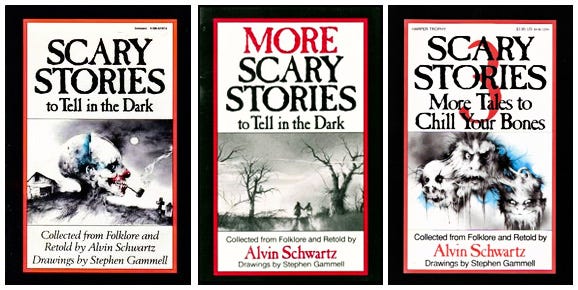

First published in 1981, Alvin Schwartz’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark and its two sequels have become a famed rite of passage for many young readers. Skillfully adapted from folklore and urban legends, the stories are gory, disgusting, psychologically complex, and frequently violent, with just enough humor to keep you turning the pages even after you knew reading just one more meant a nightmare or sleeplessness. As skillful as Schwartz’s writing is, the books were also famous for Stephen Gammell’s haunting illustrations which accompanied each story. Together, the writer and the artist created one of the most enduring and memorable works of children’s literature published in our lifetime.

Anne Valente and I first met in the MFA program at Bowling Green State University. While there, we discovered our mutual admiration of the Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark books, which were foundational reading experiences for both of us, certainly influencing the writers we’d become. Here, we offer readings of some of our favorite tales from the series, unpacking not just what moved us and scared us as children, but what continues to provoke and maybe terrify even now.

A New Horse (Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark):

MB: One of the first things that strikes me now about most of Schwartz’s stories is how short they are: “A New Horse” is less than two pages, and that’s fairly typical of many of the stories in the collection. Schwartz’s stories have been cut all the way down to the bare essentials, and it creates some additional weirdness, some blankness behind the details that begs the reader to fill in what is not revealed, similar to the kinds of flatness and abstraction you’d find in a fairy tale. In “A New Horse,” two farmhands share a room, with one of the farmhands sleeping terribly. Eventually he confesses that “an awful thing happens every night,” saying that “a witch turns me into a horse and rides me all over the countryside.” The farmhands switch beds, and sure enough that night the witch — “an old woman who lived nearby” — enters the room, paralyzes him with “some strange words,” and then slips a bridle over his face, turning him into a horse then riding him cross country to “a house where a party was going on,” with “a lot of music and dancing.” Schwartz writes: “They were having a big time inside.” The story goes on to explain the farmhand’s escape, and his revenge — he returns himself to human form, then goes into the house and bridles the witch, turning her into a horse before having horseshoes nailed to her feet at the local blacksmith — but despite the vengeful ending it’s the farmhand’s undetailed journey into the house I’m most curious about. What kind of gathering was this, that the witch needed to arrive riding a man-turned-horse? “They were having a big time inside”: How disturbing is that single sentence description of the goings-on? And who are these people? I think immediately of the “grave and dark-clad company” of Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown,” perhaps now having taken their party inside. And for a brief moment our young farmhand is in there among them, in a space that in my imagination is not merely the inside of a house, but some more terrifying and changeable space, like the upper rooms in Brian Evenson’s “Two Brothers,” like the expanding interior landscape of Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves. The end of the story is intensely satisfying — as revenge almost always is, at least on the page — but I do not want to be at the end of the story. I want to be several paragraphs back, back inside that house, walking alongside the farmhand with the bridle in his hand, hunting witches throughout the “big time” happening in every room.

Room For One More (Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark):

The brevity that you mention is something I noticed immediately upon rereading these stories — as a child they seemed expansive and neverending, almost nightmarish in the inability to escape from thinking about them.

AV: The brevity that you mention is something I noticed immediately upon rereading these stories — as a child they seemed expansive and neverending, almost nightmarish in the inability to escape from thinking about them. The lack of revelation in the “big time” of “A New Horse” happens again a few pages later in “Room for One More,” another story that’s only a page long where a man visiting Philadelphia on a business trip wakes in the night and sees a hearse out his window, and the driver calls to him, “There is room for one more.” The next day on his way back from his business meeting, an elevator opens and the driver of the hearse is waiting inside among a crowd of people. The driver tells him again that there is room for one more and when the man declines, the elevator closes and then plummets, killing everyone on board. In this brief story, the minimalism of the language creates questions and also space for the reader’s imagination. When the man first awakes in the night, Schwartz writes, “In the moonlight, he saw a long, black hearse filled with people.” The hearse is clearly described, but what of the people? Are they ghostly? Do they look alive? Are they the same people who appear the next day in the elevator — along with the driver of the hearse, the only person identified — a space Schwartz describes only as “very crowded”? These people are given a voice in the last lines of the story, their “shrieking and screaming” apparent as the elevator falls down the shaft, but never faces. Their absence haunts what’s on the page.

The Appointment (Scary Stories 3):

MB: These are good examples of one of the things that it can take time to learn as a writer: Just because a reader asks questions doesn’t mean the reader would be more satisfied if the answers were on the page somewhere. What creates part of the effect you’re describing is how wherever the logic of a story isn’t explicitly revealed by the teller, it has to occur in the reader. In a similar vein, “The Appointment” tells of a sixteen-year-old boy who sees Death beckoning to him from the main street of his town. He rushes home to his grandfather, begging to take the grandfather’s truck to flee into the city, where he believes Death won’t be able to find him. But when the grandfather later runs into Death later in the day, he chastises Death, saying “Why did you frighten my grandson that way? He is only sixteen. He is too young to die.” Death apologizes, saying he hadn’t meant to scare the boy. He was simply taken by surprise: “You see,” Death says, “I have an appointment with this afternoon — in the city.” It’s a very simple story, barely a half-page long — it’s a struggle to summarize it without just repeating it — and in his notes Schwartz acknowledges that the story has several famous variants. When I was just starting to write seriously, around nineteen or twenty, an older writer introduced me to W. Somerset Maugham’s work, including his “The Appointment in Samarra,” which John O’Hara used as the epigraph of his novelof the same name. Reading Maugham’s version of this story years after last reading the version in the Scary Stories books — and maybe hundreds of years after the tale first appeared in oral form in Asia — I experienced a kind of double chill: First the elegant reversal in the story itself — we relished our protagonist’s escape from Death, but now we find that his efforts has only sealed his doom, a twist that is also a sudden denial of free will, of control over our destiny — then the déjà vu of the retelling itself, of reencountering a story that you have forgotten but whose beats are now delivered again in nearly precisely the same way, to the same powerful effect: In the years since you last heard this tale, each new telling asks, did you start to imagine again that you actually have free will? That there’s anything you can do to forestall the hour of your death?

Oh, Susannah (More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark):

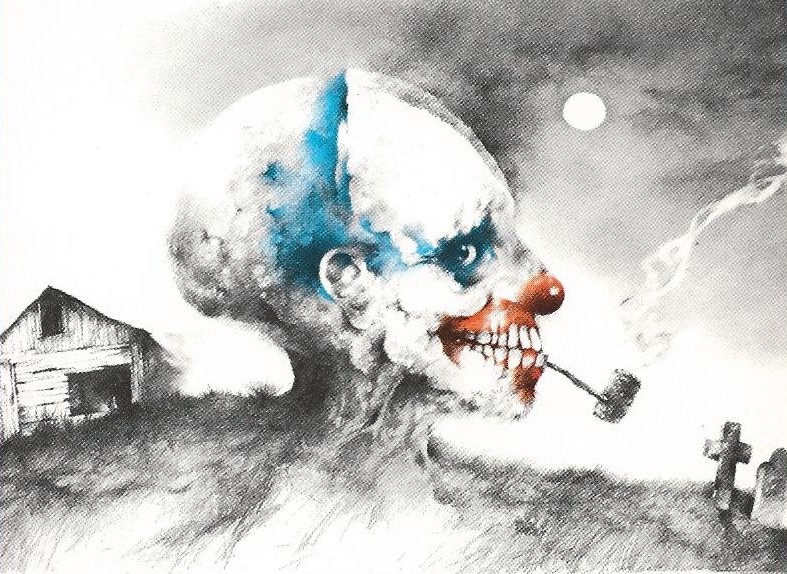

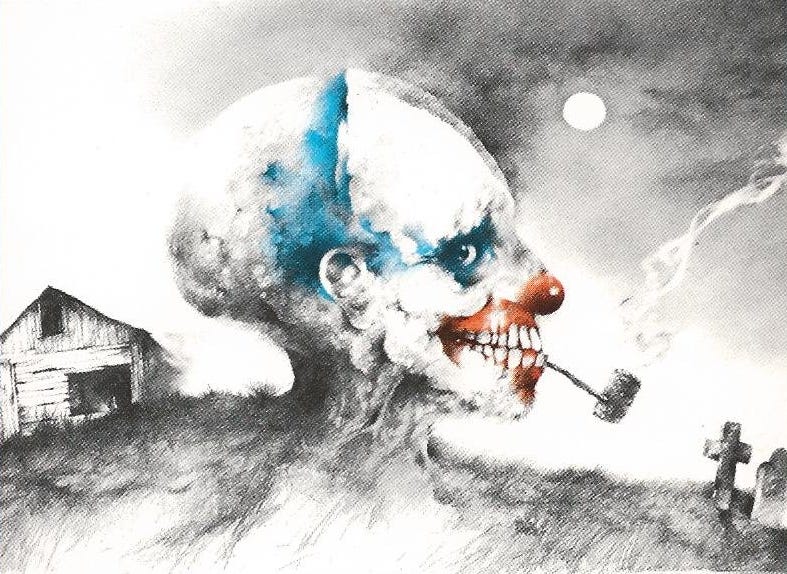

AV: One of the things that makes these stories even more frightening is Stephen Gammell’s illustrations, black-and-white sketches that are so surreal and haunting. The image accompanying “The Appointment” — a grim reaper pointing to a truck floating in the sky — isn’t dissimilar to the image that appears with “Oh, Susannah,” one that actually gave me nightmares last night after digging back into these books. Here, the image is of a rocking chairing float in the sky, above which a monster’s face emerges from the clouds. The image isn’t that closely related to the story, which follows a university student returning to the apartment she shares with a friend and finding all of the lights out. She leaves the lights off, assuming her roommate is asleep, but as she tries to fall asleep she hears someone humming the tune to “Oh, Susannah.” She tells her roommate to be quiet and drifts off to sleep, and in the night reawakens to hear the same tune being hummed. She shouts at her roommate to stop and receives no answer, and after drifting back to sleep she awakes in the morning to find her roommate decapitated. The image isn’t a match for this story but enhances its nightmarish quality, occupying the facing page. As with “The Appointment,” this story ends with the narrator thinking she has free will but doesn’t. She simply goes back to sleep, whispering to herself that she’s having a nightmare and that when she wakes everything will be alright, but as readers we know this isn’t true.

Something Was Wrong (More Scary Stories):

MB: In “Something was Wrong,” we have the opposite situation: Here our protagonist awakes in a strange place, unable to understand what’s happened to him. John Sullivan is dead but doesn’t know it, and so as the story opens he’s in a sort of fugue, wandering the streets: “He could not explain what he was doing there, or how he got there, or where he had been earlier. He didn’t even know what time it was.” A series of brief interactions with others fails to answer John’s questions — a woman screams and runs away, a few undetailed strangers “[flatten] themselves against a building, or [run] across the street to stay out of his way,” a taxi driver speeds off after a single look — but maybe a smart reader guesses even before John calls his house to find out that his wife is not home, that she has gone to his funeral, taking place that very moment. It’s a very simple story, but when I read it as a devoutly Catholic child, I think it might have spoken to my fears that after death I would not go to heaven, or in this case even to hell, instead ending up only in some limbo or purgatory served on earth. What could be worse? As a more secular adult — who, as he reads these stories, has to continually remind himself that he does not believe in ghosts — I’m now struck mostly by the ending, how the tale finishes not with resolution but with a punchline: John has learned he’s dead, and we’re supposed to be either caught by surprise or else delighted that we figured it out before he did. But really, John’s story has just begun: Yes, John’s dead, but what’s next? That’s the most interesting part of the story, and it’s left entirely up to the reader.

Yes, John’s dead, but what’s next?

The Babysitter (Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark):

AV: That kind of open ending differs from some of the closed endings of Schwartz’s tales, like “The Babysitter.” In this well-known story, a babysitter for three children keeps getting phone calls that grow more menacing as the night wears on. Every half hour, a man whispers a countdown to the babysitter on the other end of the line. After the fourth call, the babysitter calls an operator who traces the fifth call. Just as the operator tells the babysitter that the call is coming from upstairs, a door opens at the top of the stairwell and a man emerges with a knife. The ending is closed: the police arrive, and the main is arrested. But questions still linger for the reader, the opening up of the possibility that this kind of thing can even happen. If I try to think about why this story was so terrifying to me as a child, especially since I only babysat a few times in teenhood, it’s the notion of seemingly safe borders being permeated: the domestic setting of a house, the surety of locked doors. Like many other urban legends, this story also features a man preying upon a young woman, not unlike Arnold Friend in Joyce Carol Oates’s “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” where an older man tracks a teenage girl, and where a locked screen door becomes a thin boundary between safety and danger. That story leaves the reader with an open ending, whereas here, the babysitter is resourceful enough to call the operator and the police arrive. But the terror of this occurrence lingers beyond the final lines, that there was a man upstairs the entire time the babysitter watched these children.

The Bride (More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark):

MB: It’s coming from inside the house! That’s become such a horror movie trope, and probably every generation will have their version of it. (That said, “The text message is coming from inside the house” is somehow not very scary.) I like the connection you made between “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” and urban legends: Like you, many of the ones I remember are cautionary in nature, about the danger of crossing different thresholds. I grew up in a house surrounded by woods, and I frequently spent the days playing in them happily with my brother. But at night the woods were a completely different thing: I used to try to see how far I could walk out into them without getting scared and having to run back to the house, and it was never as far as I wanted it to be, even though I knew there wasn’t anything to be afraid of — nothing except that the backyard of our house was manicured and fenced and lit and safe, and the world beyond it was none of those things. In “The Bride,” Schwartz gives us another rare story with nothing supernatural in play: A minister’s daughter gets married, and after the celebration there is “music and dancing and contests and games, even old children’s games.” This is the trick of the story, I think: It creates tension not through the supernatural but by twisting the everyday. The wedding party begins to play hide-and-seek, and the bride hides in the attic, inside “her grandfather’s trunk,” her preacher father’s father’s trunk. The lid falls upon her, knocking her unconscious and then locking her inside. (And why was the chest unlocked when she found it? And why was it stored empty in the attic? What did it used to contain, before it contained the bride?) The wedding party searches for her, but her screams can not be heard from inside the trunk and eventually she dies. And this too was a childhood fear I remember all too well: That I would walk into the woods and at last go so far past my fear I might not be able to make it back home. That I would close my eyes and count to a hundred at the start of a game of hide-and-seek and when I opened them I would never find my brother, or else when it was my turn to hide I would not be found either. I remember the creeping terror that comes from choosing a particular good hiding spot: As the seekers expand their search, the sound of their hunting quiets, their movement perhaps now somewhere beyond the limits of your hearing. And how long do you wait? How long can you stand to be alone, in a place where no one who cares about you knows where you? At what point does that game stop being fun? The minutes were so much longer when we were kids. Inside them it could become horrible to be alone and lost even in a hidey-hole of your own making, even for the length of a single game.

A Ghost in the Mirror (More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark):

AV: The focus on games — hide-and-seek, and the point at which fun turns to horror — is at play in “A Ghost in the Mirror” too, along with the same terror that something as familiar as your backyard can quickly become defamiliarized and dangerous. Less story and more instruction manual, this tale begins, “This is a scary game that young people sometimes play,” even though it’s anything but a game: the story outlines the history of Bloody Mary and how to conjure her in a bathroom mirror. Schwartz discusses the possible origins of the Bloody Mary legend, from the ghost of Mary Worth who was allegedly hanged in the Salem Witch Trials to La Llorona, a “weeping woman who wanders the streets of cities and towns from Texas to California and throughout Mexico, looking for her lost child.” Much like other urban legends, the terror of this tale is the permeability of borders, only this time a lack of definition between a ghostly world and our own. As Schwartz mentions in the instructions to conjuring Bloody Mary, “If [the ghost] is angry enough, they say, it will try to shatter the mirror and come right into the room.” What is more terrifying to a kid than the notion that a ghost can break through a mirror and enter one’s house and world? As a child, after reading this tale and after seeing Candyman and after witnessing a group of girls try to conjure Bloody Mary in my elementary school bathroom, I removed the mirror from my bedroom in fourth grade (it didn’t return until I was well into high school). Schwartz writes that the conjurer “can always turn on the lights and send the ghost back to where it came from.” But who can be sure? A border has been crossed. A border as mundane yet entirely frightening as a bathroom mirror.

The Haunted House (Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark):

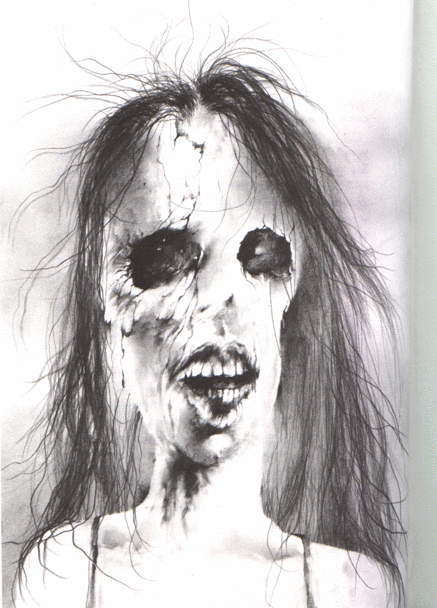

MB: What I want to know now is: Where did you keep your mirror in the decade it wasn’t on your wall? I gave myself a good chill at the thought of the mirror under your bed, face up and reflecting the dark beneath, half-loaded with one or two namings of Bloody Mary, just waiting for you or someone else to slip up just one more time. Do you know that there are Youtube clips of teenagers playing Bloody Mary? Testing the thresholds of reality, Millennial-style. “The Haunted House” is a story that taps the same anxious vein, about a preacher who spends the night sitting up and reading his bible in a house “in his settlement” that has been “haunted for about ten years.” (The “settlement” is such a telling detail: These are old stories, taking place in more dangerous days.) In one of those serendipitous moments where the page layout amplifies the story, we’re told that when the preacher finally sees “the haunt” (not a ghost, but a haunts!) that it “looked like a young woman.” And then, in my edition at least, you turn to the page to find one of Gammell’s most terrifying illustrations, perhaps the one I remember most vividly across all the years between readings of these books. “It look liked a young woman,” Schwartz writes, but this young woman has no eyeballs, just “a sort of blue light way back in her eye sockets,” and “no nose to her face.” Her hair is “torn and mangled,” and “the flesh was dropping off her face so he could see the bones and part of her teeth.” It’s one of the most literal illustrations in the books, and one I will never not have lurking somewhere in among my synapses, waiting to be triggered again. Reading the story again, I’m also once more struck by how skillfully Schwartz sometimes turns a phrase. When the haunt starts speaking — and how much better of a noun is “the haunt” instead of “the ghost”? — it sounds “like her voice was coming and going with the wind blowing it.” That’s vague in a really spectacular way, a kind of description that requires a little work from the reader. And horror is all about getting the reader to imagine something worse than anything you might put directly on the page: What exactly does it sound like when a voice is “coming and going with the wind blowing it”? And why does it get more disturbing the more precisely I try to imagine it?

The Trouble (Scary Stories 3):

AV: That phrase was the one that stood out to me most in the story as well too, and I appreciate that subtle attention to language in Schwartz’s stories (and that image has also stayed lodged in my brain for more than twenty years now). “The Trouble” is equally interesting on a language level, but written with a heightened attention to precision rather than leaving much to the reader’s imagination due to its structure as a daily log of paranormal activity. One of the longest stories in the collection (seven pages!), this tale recounts a strange month in the Lombardo household where caps explode from bottles, record players fly through the air and crash to the floor, and in the most delicious of details, “a bookcase filled with encyclopedias fell over and wedged itself between a radiator and a wall.” The family hires Detective Briggs, a “practical man” who calls upon “an engineer, a chemist, a physicist, and others,” to help find a logical explanation for this trouble. Scientific hypotheses follow, including the possibility that vibrations from radio waves or underground water are causing objects in the house to move. The tension in this tale comes from the conflict between knowing and not knowing, and between reason and what can’t be explained by logic. Try as they might, Detective Briggs and his team of scientists can’t fully explain what is happening to the Lombardos. Schwartz writes, “Then what was causing the trouble? None of the experts knew.” This breakdown of authority’s ability to explain is never answered with reason and leaves more questions — for the reader and for the Lombardo family — than answers.

The Dream (Scary Stories 3):

As a reader, I can’t see any escape from the room, and so even after Lucy Morgan escapes perhaps I am still there.

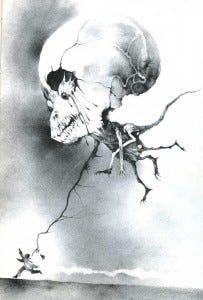

MB: I love “The Trouble” too, and I think there’s something really interesting about how despite its extended length we still end up at a place of not-knowing. Another that resists easy explanation is “The Dream,” about an artist named Lucy Morgan — there’s something so certain about being offered her first name and last name, so solid and reassuring — who has a dream about a “woman with a pale face and black eyes and long black hair” who comes into her room at night to warn her that the house she’s sleeping in is “an evil place.” This story is also accompanied by one of Gammell’s oddest drawings, of the pale-faced woman: her mouth a wide straight line that somehow still seems to be smiling, her small black eyes, her long hair falling over what appears to be a naked but featureless body, without breasts, without a navel, with no distinguishing marks of any kind. Down in the lower left of the page, we see the fingers of one hand, gripping a featureless white object, a wall or a divider or else the frame of Lucy Morgan’s bed, the dream-bed or else the one she finds herself in a few days later, when she escapes to another town, renting a room she realized she’s seen in her dream, “with the same carpet that looked like trapdoors and the same windows fastened with big nails.” It’s a room with two fake escapes — trapdoors that are just carpet, windows that can’t be opened — and then the door opens, revealing “the woman with the pale face and the black eyes and the long black hair,” the woman’s name not a name like Lucy Morgan but instead just this long phrasal noun that carries with it everything you can ever know about her. In the last sentence of the tale, Lucy Morgan flees — but how, with the fake trapdoors and the fastened windows and the woman standing in the doorway? As a reader, I can’t see any escape from the room, and so even after Lucy Morgan escapes perhaps I am still there.

The Red Spot (Scary Stories 3):

AV: That sense of nightmare — of dreamscape, of lack of escape — seems crucial to these stories, and maybe even to why we’re still talking about them today, over thirty years since the first of the series was published. Sitting down to read these now, I’m still there, still in elementary school and still under the covers with a flashlight. In the same section as “The Dream” — fittingly entitled Five Nightmares — is another Schwartz tale that stayed with me. There’s nothing supernatural about “The Red Spot” and it ends with a clear explanation, but the accompanying illustration is what continues to haunt me. The story is about a woman who wakes to find a red spot on her cheek. The story is only half a page long but across that page the spot grows into a boil and keeps getting bigger. At the end of the story the boil bursts while the woman is in the bathtub, releasing a “swarm of tiny spiders from the eggs their mother had laid in her cheek.” The ending is cut and dry. The story is horrific in a gross way but doesn’t require much imagination from the reader. But it’s the illustration that still gets me. Much like the close-up of the woman in “The Dream,” this story’s black-and-white sketch is of a woman open-mouthed in horror as a dripping splotch of blood and small spiders spreads across her face. The woman is ghostly. As with all of Gammell’s illustrations — and all of Schwartz’s tales — reality bends and shapeshifts just beyond recognition. The scaffolding falls away. Something surreal and haunting takes its place.

This story shares what all of Schwartz’s stories share, whether they’re supernatural or reality-based, whether they move toward closed or open endings: all of these stories create a deeply unsettling mood and tone, and all of them push our understanding of the world further off kilter. I hope to create a similar sense of not-knowing in my fiction now, some sense of wide-open possibility in the language that leaves room for the reader’s imagination, and some sense that the world is filled with strange and mysterious things that can be discovered by nothing more than an active sense of curiosity, a willingness to believe.

In the decades since their publication, the Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark books have been among the American Library Association’s most challenged books, with would-be censors decrying the violence in the stories and in the illustrations. In 2011, publisher HarperCollins “celebrated” the 30th anniversary of the series by replacing Stephen Gammell’s strikingly nightmarish art with much tamer, more clearly representational art by Brett Helquist. It’s one of the more obvious examples of a publisher not understanding what made a book special in the first, revising a wildly successful property into a less risky and less unique product. In our hearts, the original versions of the books will always be the only acceptable choice, and we hope new readers will seek out old copies in libraries and used bookstores, on the shelves of older siblings and friends, and surely, by now, on the shelves of their parents, who might still be able to tell you exactly what page certain illustrations are waiting on, the images and the words they accompany surely no less terrifying now than they were three decades ago.

Anne Valente is the author of the short story collection By Light We Knew Our Names, recently released from Dzanc Books. Her fiction appears or is forthcoming in One Story, Ninth Letter, Hayden’s Ferry Review and The Normal School, and her essays appear in The Believer and The Washington Post.