Books & Culture

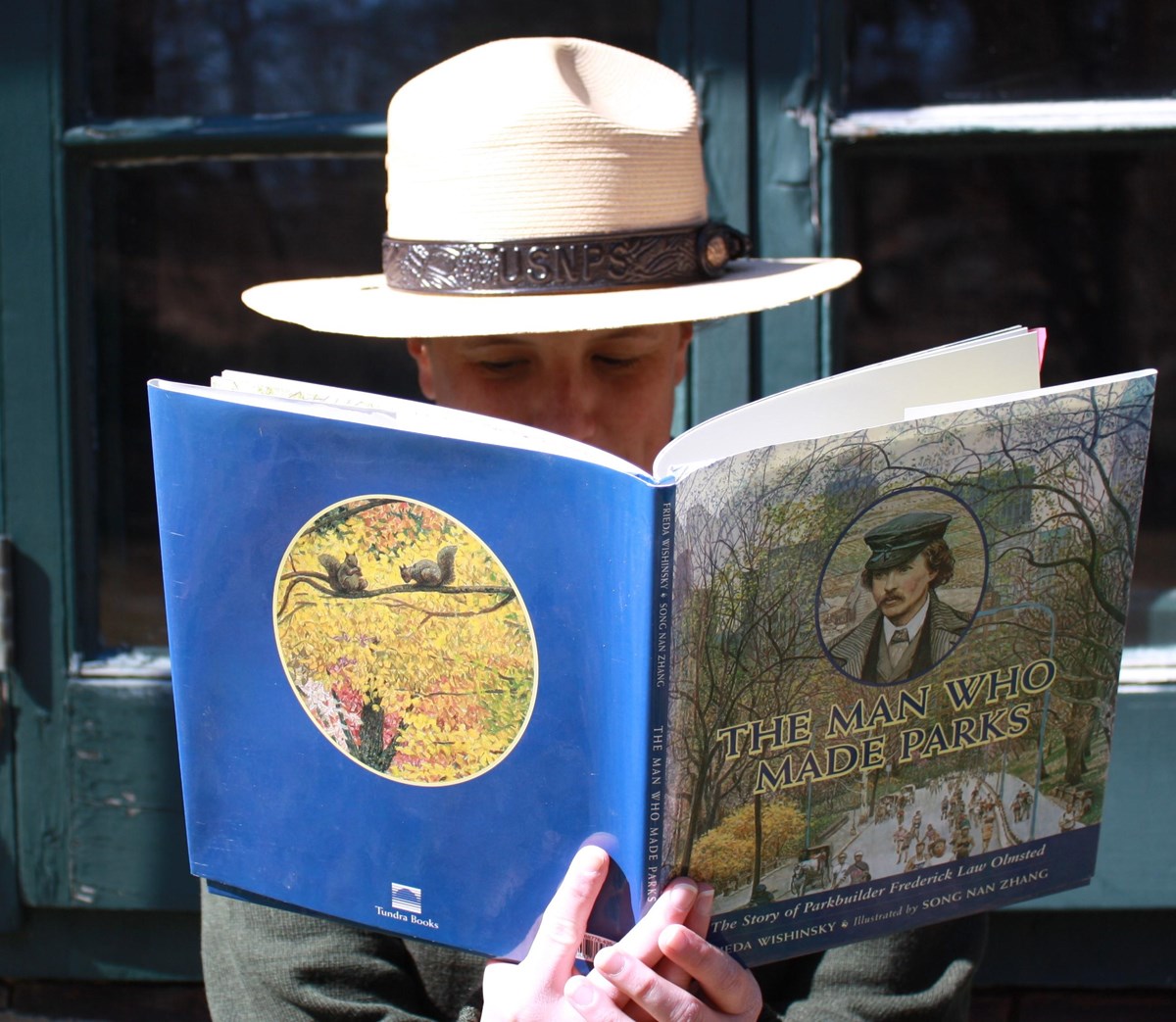

Literary Artifacts: Why Children’s Books Matter

Five months before my son Joshua was born, I began reading to him at bedtime; it was my first real job as a father. All the baby books said that he’d already developed tiny ears and reading aloud to him might be good for his development. So each night I’d press a cheek against my wife Leah’s stomach, hoping the vibrations of my voice would (maybe) carry as I read him The Wind in the Willows.

I liked imagining that Joshua was following along with the story, even though I knew he couldn’t yet understand a word of Kenneth Grahame’s 1908 classic. What surprised me was how often I struggled to understand it myself. It didn’t seem at all like a book meant for children. Sure there were adorable anthropomorphic woodland creatures, but there were also words like “bijou”, “telegraphic”, “phosphorescence”, and “raiments.” I couldn’t quite see a modern child enjoying chapter nine’s long digression about the pleasures of the “wayfaring life,” though I certainly did. Chapter seven, entitled “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” contains passages so perplexing, poetic, and psychedelic that I wasn’t at all shocked to learn it made a huge impression on young Syd Barrett and Roger Waters, who later named the first Pink Floyd album after it. Night after night I jumped into bed anxious to read a little more of the book. Most of the time I forgot I was supposed to be reading to Josh.

Truth be told, I was enjoying the adventures of Rat and Mole and Mr. Toad much more than the adult novels I was reading during the daytime.

After Josh was born, we moved on to Peter Pan, which is delightfully dark and death-obsessed, with complex psychological concerns. Peter cannot form lasting memories because then he might learn from them, and thus, like the rest of us, grow-up. At several points he forgets he has killed someone. He can neither return Wendy’s pre-teen affections nor understand Tiger Lily’s advances after he saves her from drowning. “There is something she wants to be to me, but she says it is not my mother,” he complains to Wendy. Like Peter, younger readers wouldn’t get this; it’s clearly a joke meant just for the adults. Similarly, their little hearts don’t break like mine did when, at the end of the book, Wendy asks Peter about Tinker Bell — the fairy who drank Captain Hook’s poison to save the hero’s life. Peter shrugs. “Who is Tinker Bell?” he asks.

Reading these books each night I cannot get over how grown-up they feel. Sometimes the only thing that seems childish about them is that they trust their readers to play along. No one cries “postmodernism!” as they abruptly change tenses or directly address the reader. Of course these books predate postmodernism, and even modernism, by multiple decades. They are not interested in founding movements, only entertaining and surprising their young but discerning audience. W.W. Norton has done oversized Critical Editions of both these books, and also of Lewis Carroll’s classics Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Each is rife with as many footnotes, appendices, and interpretations as a copy of Ulysses, and the playful weirdness of these books makes me wonder if a young James Joyce didn’t grow up reading them. In fact, in one such note, literary critic Robert Polhemus argues exactly this. “From out of the rabbit-hole and looking-glass world come not only such major figures as Joyce, Waugh, Nabokov, Beckett, and Borges but also much of the character and mood of twentieth-century humor and life.” Additionally, novelists as diverse as Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Ben Okri, and Haruki Murakami have cited Alice as a major influence on their work.

In another essay, Polhemus explains why returning to children’s literature can be so inspiring to adult readers and writers:

“The way to go forward in looking-glass land is to go backward — back to origins, first principles, early years, early pleasures, and premoral states — in order to see with fresh clarity what, through habit and social repression, we have come to accept as absolutely the truth and to find in a place of make-believe that make-believe is the essence of our fate and being. […] The intention that comes through in Through the Looking Glass is, in effect, the meaning of mankind’s comic capacity, and it is this: I will play with and make ridiculous, fear, loneliness, smallness, ignorance, authority, chaos, nihilism, and death; I will transform, for a time, woe to joy.”

Perhaps this is what I am suddenly so nostalgic for, each night. I can still remember when books stopped doing what Polhemus is describing.

Right around middle school, the fun books suddenly disappeared. Dreary realism replaced fantasy.

Read Hatchet. Read Shiloh. Read Sounder. Read The House of Dies Drear. Read about kids in the Great Depression, whose dogs always die. Read about the gruesome fact of slavery. Read about Anne Frank in the attic. Today, class, we’ll be reading a graphic novel! …it’s called Maus. No wonder I kept my nose buried deep in Dragonlance novels and The Collected Calvin & Hobbes.

Eventually I accepted that the mark of serious, grown-up books was joy turning into woe. Merry old Gatsby is really a huge fraud who bites it in a swimming pool and no one cares but his neighbor. The end. Jake Barnes is living it up in Paris with Brett Ashley, but he got injured in the war and they can’t have sex, so… the end. The older I got the more books seemed to skip the joy part altogether — they just went from woe to more woe. The Joads are starving in the Great Depression so they head West but find that everyone else is starving too and then somebody dies in the back of a truck… the end. Frank and April Wheeler are hopeful suburbanites who dream of moving to Paris but then she gets pregnant and dies trying to give herself an abortion. The end!

Of course I’m overstating the case. There is plenty of joy and beauty in these tragic stories. And it is good that we teach our children hard truths about death, poverty, slavery, religious intolerance, and genocide. Someday I hope my son will read every one of these books; I just hope he has something that can bend woe back to joy again afterwards.

Recently at an event sponsored by Pen Parentis, an organization supporting writers with new children, a discussion arose about whether the books we read to our kids have any influence on our own writing. Do they make us think harder about what we’re trying to say, or what we’re putting out into the world? The other writers and I hemmed and hawed about how, as fiction writers, we don’t have any direct thesis or message — but deep down

I knew that re-reading Winnie the Pooh each night was making me think a lot about what I wanted to write and what I was trying to say.

A.A. Milne’s little books do not contain any blunt moral instruction, but there are plenty of lessons to be learned in the Hundred Acre Wood: the importance of friendship, the dangers of xenophobia, that even Very Small Animals can be brave on Blustery Days, and to not eat so much that you get stuck in a burrow. The other animals all look up to the wise Owl, though he misspells his own name, WOL. Reading this little irony, I look forward to the day my son can get the joke — but there is more to it than just a laugh. Later, Milne remarks on why Owl is so admired, “You can’t help respecting anybody who can spell TUESDAY, even if he doesn’t spell it right; but spelling isn’t everything. There are days when spelling Tuesday simply doesn’t count.”

There are days when spelling Tuesday simply doesn’t count. That’s what I really can’t wait for my son to understand. It’s something I find myself saying to myself almost every day now.

That’s woe transformed to joy, right there.

Right now my joy comes mainly in watching Josh try to eat the pages of these books. But sometimes when we read his Cozy Classic Moby Dick (featuring delightful fabric-rendered characters) he will reach out and grab the bottom corner of the page and flip it over to get to the next picture. Is it my imagination or is he a little awed when he looks down at felt Captain Ahab? According to a recent piece by Julie Bosman in The New York Times, lots of parents like us are buying these “BabyLit” books to read to their kids, with cartoon Jane Eyres and Jean Valjeans on every page. I like to think that someday when he reads the real novels they’ll feel just a little more familiar to him — a little cozier.

In the meantime we’re taking our old children’s books out of storage, and I have so much to look forward to again on my reading list. We’re coming up on Leah’s old copy of Charlotte’s Web and my Phantom Tollbooth, with “KRIS J” written in permanent marker on the inside cover.

After storytime each night, as Josh’s eyes begin drooping, we rock him out in the hallway by our own bookshelves, the darkest spot in the apartment besides the bathroom. When he won’t sleep, Leah holds him up so he can reach the spines and pat them. “This is a cloth-bound book,” she says, “and this is a paperback, and here’s a hardcover…”

And someday they will all be his.