Lit Mags

Ghost Solicitors Not Allowed

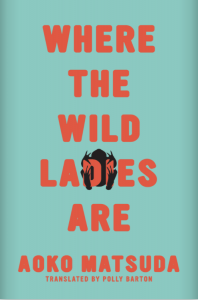

"Peony Lanterns" by Aoko Matsuda, recommended by Carmen Maria Machado

Introduction by Carmen Maria Machado

If there is a specific subgenre of ghost story of which I am inordinately fond, it is the one in which the protagonist has sex with a ghost. It has all the unease of Celtic folklore’s cardinal rule about eating or drinking of Fairy food (“bite no bit and drink no drop”); the idea that to consume something tempting of the other world is the fast track to possession, insanity, or death. In Washington Irving’s “The Adventure of the German Student,” for example—an early prototype of the “woman with a ribbon ‘round her neck” story—a young man living in France during the Revolution makes love to a woman with a black band around her throat. Only afterwards does he realize she’d been decapitated by the guillotine the day before. He tells this story from a madhouse, natch—he is convinced that an evil spirit has “ensnare[d]” him and dies soon afterwards.

If there is a specific subgenre of ghost story of which I am inordinately fond, it is the one in which the protagonist has sex with a ghost. It has all the unease of Celtic folklore’s cardinal rule about eating or drinking of Fairy food (“bite no bit and drink no drop”); the idea that to consume something tempting of the other world is the fast track to possession, insanity, or death. In Washington Irving’s “The Adventure of the German Student,” for example—an early prototype of the “woman with a ribbon ‘round her neck” story—a young man living in France during the Revolution makes love to a woman with a black band around her throat. Only afterwards does he realize she’d been decapitated by the guillotine the day before. He tells this story from a madhouse, natch—he is convinced that an evil spirit has “ensnare[d]” him and dies soon afterwards.

Aoka Matsuda’s “The Peony Lanterns” revisits the traditional Japanese ghost story “Botan Dōrō,” in which a man (sometimes a young student, sometimes a widowed samurai) falls in love with a beautiful woman who appears nightly with a handmaiden bearing a lantern. When someone—alternately a neighbor or a servant, depending on the telling—grows suspicious and spies on the man, they discover him having sex with a decaying corpse. A charm is placed on the house, to keep the owner safe. But the woman returns and cries out for her lover, who is unable to resist and goes with her. The next morning, his dead body is discovered with her skeleton.

In Matsuda’s retelling, we see a different kind of common figure—a man who has lost his job and by extension, his sense of purpose. What does it mean when two mysterious saleswomen bearing a simple and achievable task arrive, as if by a dream, in his living room? Here, the pleasure of the flesh is replaced by the pleasure of the purchase; they offer peony lanterns, yes, but also an illusion of expertise, a former life. What does it mean, the story asks, to want something that you cannot have, and that was never real to begin with?

– Carmen Maria Machado

Author of The Low, Low Woods

Ghost Solicitors Not Allowed

Aoko Matsuda

Share article

“Peony Lanterns”

by Aoko Matsuda

translated by Polly Barton

“Good evening to you, sir!”

He’d ignored the doorbell three times already when he heard the woman’s voice carrying through the thick steel door. Sitting on his sofa, Shinzaburō froze in alarm, hardly breathing. His body felt terribly heavy, and the thought of getting up was unbearable. Usually in this situation, Shinzaburō would have relied on his wife to answer the door, but with it being Obon, she was away visiting her parents. Besides, it was ten o’clock at night. Shinzaburō had no idea who his visitor was, but he believed that ringing people’s doorbells at this hour was unreasonable behavior—and Shinzaburō disliked people who behaved unreasonably. From a young age, he had been instilled with a firm grasp on what was and wasn’t reasonable. In his adult life, throughout his career as a salesperson, his professional conduct had always been eminently reasonable. Even when he’d been laid off as part of the company’s post-recession restructure, he had retained his sense of reason and walked away without a fuss.

That had been over six months ago. Shinzaburō’s wife had begun dropping gentle hints that he should find himself another job. He knew she was right—but somehow he couldn’t bring himself to do it. Both his mind and body felt leaden. Whenever he browsed job listings online he was hit by the unshakeable sense that he was being made a fool of, and he couldn’t stand the idea of visiting the job center either. Had he really become the sort of man who had to rely on a job center? The very idea seemed too wretched to bear. And there he’d been, believing that he was talented and had something to offer to the world. He’d gone about his life not being a nuisance to anyone, playing by the rules, acting reasonably at all times. How had it come to this?

While his wife was at work, Shinzaburō would do a bit of housework, but a token offering was as far as it went. The truth of the matter was this: spending all his time in his marl-gray tracksuit, shabby from constant wear, Shinzaburō had morphed into a big gray sloth. In the afternoon, he would lounge about on the sofa, watching reruns of period dramas and mulling over questions of no particular significance, like whether, back in the Edo period, his lack of fixed employment would have made him a rōnin. How much better that sounded than simply unemployed.

“Good evening to you, sir!”

The same voice again. From the light filtering through the living room curtain, it must have been obvious to whomever was outside that there was someone at home.

“Oh, damn it all!”

Shinzaburō got up from the sofa, slowly crept toward the door to avoid his presence being discovered—though he knew from long years of experience that such a thing was impossible—and peered through the spyhole.

Outside the gate stood two women. They were dressed in practically identical outfits: black suits, white shirts, sheer tights, and black pumps. One was somewhere between forty and fifty, and the other looked to be in her early thirties. The elder was staring with terrifying intensity at the spyhole, while the younger was shyly inspecting her feet. They made for an altogether peculiar pair. Immediately, alarm bells went off in Shinzaburō’s head. No one in his right mind would involve himself in a situation he knew would be troublesome from the outset. In this particular period of his life, Shinzaburō did not have the mental energy to spare on that kind of nonsense.

The women seemed to sense Shinzaburō’s presence in his cramped entranceway, and the elder one piped up again. “Good evening to you, sir!”

Shinzaburō guessed she must be the one who had done all the speaking so far. The younger one kept her head down, not moving a muscle. Something about the way she held one cheek angled toward the door suggested she was invested in what the person on the other side thought of her. Indeed, the way she carried herself was common among highly self-conscious women, thought Shinzaburō. The observational skills he had cultivated during his years as a sales representative, which enabled him to pick up on these little details about people, was a source of great pride to him. Very cautiously, Shinzaburō opened his mouth.

“Yes, what is it?”

“Oh, good evening, sir,” began the elder woman with an affected smile on her face. “We are door-to-door sales representatives, visiting the homes in this area in the best of faith. We are terribly sorry to disturb you at this hour, but we were wondering if you might be able to spare us a couple of minutes of your time.”

Something about the woman’s voice filled Shinzaburō with instantaneous exhaustion. He felt nothing but loathing for these stupid women who’d invaded his precious relaxation time and forced him to walk all the way to the front door. Don’t you know that I’m exhausted? he wanted to say. For six whole months now, I’ve been totally and utterly exhausted.

“No thanks, I’m afraid not. It’s late.”

No sooner had Shinzaburō delivered his curt answer, which he had hope would make them go away, than the younger one, who had been examining the floor so intently, raised her head to look toward the spyhole, and said in a weak, sinuous voice, “Come now, don’t be so inhospitable! O–pen up!”

If a willow tree could speak, Shinzaburō thought, this is the kind of voice it would have. He blinked and found himself in the living room, the two women facing him across the coffee table. As if that wasn’t bad enough, they were sitting on the sofa, while Shinzaburō had been relegated to one of the more uncomfortable kitchen chairs he and his wife had bought online. He had no memory of carrying it into this room. Sandwiched beneath his buttocks was one of the Marimekko cushions his wife loved so much. Shinzaburō still had no idea what its pattern was supposed to represent, although right now that was hardly his most pressing concern.

While Shinzaburō was still wondering how on earth he had wound up here, the women sat looking at him, their four stockinged kneecaps arranged into a perfect row of iridescent silver. Seeing that they had his attention, they both pulled the same inscrutable expression and handed him business cards as white as their papery faces.

“Allow us to introduce ourselves.”

Flummoxed by being handed two cards at exactly the same time, Shinzaburō somehow managed to accept both and examined the names printed on them. The elder woman was Yoneko Mochizuki, the younger Tsuyuko Iijima.

Just then, Shinzaburō’s eyes fell on three steaming cups of green tea placed on the coffee table. Did I go and make tea without realizing it? he thought. Surely these two didn’t sneak in to the kitchen and make it themselves? What’s more, he noticed that the yōkan he’d been saving for a special occasion was there too, cut into neat slices. As Shinzaburō was trying to wrap his head around all this, Yoneko spoke.

“We took the liberty of examining the nameplate outside your door. It’s Mr. Hagiwara, is that right? Oh, good. Forgive our impertinence, but may we ask your first name?”

Why did they need to know? “It’s Shinzaburō,” he found himself saying, though he’d had no inclination to answer the question. It was as if his mouth was moving of its own accord.

“Shin–za–bu–rō,” Tsuyuko pronounced slowly.

Having his first name spoken like that by someone he’d only just met made him shudder. It was much too intimate.

“It’s an absolute pleasure to make your acquaintance, Shinzaburō.”

Between this woman’s honeyed tone and her flirtatious manner, there was definitely something overfamiliar about her. Shinzaburō averted his eyes. Did she think her looks would allow her to get away with such behavior? Sure, with her alabaster skin, her hair lustrous as a raven’s coat and all those coquettish sideways glances, she was undoubtedly beautiful. And yet, despite all these gifts, the epithet that seemed to fit Tsuyuko like no other was misfortunate.

Without waiting for an invitation, Tsuyuko took a sip of tea from her cup, leaving a sticky red lipstick mark on its rim. It came to Shinzaburō in a flash that as far as sales work was concerned, this woman was probably utterly incompetent. The same went for her companion, too.

“Well, if you don’t mind, we’ll get down to business,” said Yoneko, projecting her gray-haired head forward like a tortoise emerging from its shell. Shinzaburō nodded reluctantly, resolving to hear out their patter and then get them to leave. Changing the key of her already gloomy expression so it was positively funereal, Yoneko began to speak.

“Miss Tsuyuko here has had the most lamentable of lives, Mr. Hagiwara. She was born into a family of great repute and prestige, and yet here she is now, as you see, working all day long as a mere saleswoman. The cause of this tragic downfall was that her beloved mother passed away at a young age, leaving poor little Tsuyuko behind. Her father was a kind man, but rather weak of character, and it wasn’t long before he developed an intimate relationship with the maidservant.

As sad as it is to admit, it would appear that there are a great many weak-willed men out there. As for the maidservant, well! I know that of late people take leaks of personal information and so forth awfully seriously, but we do so much wish you to hear this story in its entirety, so I will on this occasion divulge that her name is Kuniko. Now, Mr. Hagiwara, we do most earnestly beseech you to exercise the utmost caution around women going by the name of Kuniko. For the thing is, you see, this Kuniko utilized her feminine wiles to claw her way to the stature of second wife. As if that wasn’t enough, she then resolved to gain sole possession of Tsuyuko’s father’s fortune, and began spoon-feeding him all kinds of groundless fabrications about Tsuyuko, morning and night . . . was not a man of strong character. Honestly, men like that really are the worst, aren’t they, Mr. Hagiwara? Anyhow, predictably enough, he foolishly believed every word that Kuniko spouted, and began to look coldly upon his daughter. Unable to bear this cruel treatment, Tsuyuko left home without even finishing high school. Her life from that point on has been one tear-inducing episode after another. To start . . .”

“Sorry, but why are you telling me all this?’ Shinzaburō finally broke in on her lament. For a long time, he had been stunned into silence by Yoneko’s phenomenal pace of speaking, which would have rivaled that of any rakugo performer, but eventually he managed to find his opening. “What does any of this have to do with me?”

At this obviously unexpected interruption, a look of unbridled annoyance flashed across Yoneko’s face, but she continued with a cool expression. “It has nothing to do with you personally, Mr. Hagiwara, but the fact that we have met in this way implies some kind of indelible connection between us. It’s Miss Tsuyuko’s heartfelt wish that you hear her story.”

Tsuyuko nodded in agreement, dabbing her tears with a white handkerchief that had miraculously appeared in her hand.

“You came barging in here! Does that qualify as an ‘indelible connection’? Besides, you’re acting very oddly, if you don’t mind me saying so! First, you said you were here as sales representatives, and now you’re here telling me your life story! Don’t you think that’s a bit inappropriate?”

As Shinzaburō began to lay down the laws of reason to these two utterly unreasonable women, they met him with expressions of genuine incomprehension.

“What exactly is wrong with that?”

“Now look here,” said Shinzaburō. “Don’t feign ignorance with me. I used to be a salesman too, so I know the score. Forcing your way into people’s houses and then acting like this is just not how it’s done.”

“Oh, Mr. Hagiwara! So you were in the sales industry too! Well, that only proves our indelible connection. Isn’t that just wonderful, Tsuyuko?”

“Oh yes, Yoneko!”

Shinzaburō looked on in horror as the two beamed at each other.

“But Mr. Hagiwara, your use of the past tense suggests you’ve given the profession up. Forgive my impertinence, but why is that? Would it be anything to do with restructuring, which has become so common in the business world of late?” Yoneko cocked her head and stared pointedly at Shinzaburō. This person was utterly unsuited to sales, Shinzaburō thought. Most likely she hadn’t even been through training. In his incredulity, he found himself answering her question without ever having meant to.

“Yes, that’s right. I lost my job when my company was restructured.”

As Shinzaburō spoke, he was all too aware that his head hung in embarrassment, as if of its own volition. He realized that this was the first time he’d spoken about what had happened to him to anybody other than his wife.

“Oh, Shinzaburō! What a terrible shame!” Tsuyuko said in a shrill voice, a hint of a smile perhaps meant to signify compassion hovering around her mouth. She leaned her slender body over the table toward him and rested her thin fingers gently on Shinzaburō’s forearm. Startled by the coldness of her touch, Shinzaburō hurriedly crossed his arms so as to shrug off any contact. Tsuyuko shot him a look that seemed to say, Well, fine, be like that. She turned away coyly for a moment, then looked back at him, more brazen than ever. Once again, Shinzaburō averted his gaze.

“Oh, Tsuyuko! How kindhearted you are! And what frostiness you are shown in return! Mr. Hagiwara, why is it that you feel no sympathy for Miss Tsuyuko?”

“Of course I feel bad for her, but that’s not the issue here! Besides, from what I’ve heard so far, it hardly sounds like the most unusual of tales. Every life has its dose of misfortune.”

At Shinzaburō’s words, the two widened their eyes into a charade of disbelief.

In a tone of utter astonishment Yoneko said, “My, what a horrendous age we are living in! In days of yore, anyone who beheld Tsuyuko’s great beauty and heard even a snippet of her tragic tale would be overwhelmed by sympathy and agree to commit lovers’ suicide with her on the spot! Isn’t that right, Miss Tsuyuko?”

Tsuyuko pressed her handkerchief to her eyes again and nodded with even greater fervor than before, then dissolved into gasping, theatrical sobs. She had to be faking it, Shinzaburō thought. He was getting more and more irritated with the duo’s outrageous behavior, and before he knew it, he was saying, “Okay then, what about you two? Are you not going to say anything about my redundancy? That seems pretty heartless to me! If you think I should be feeling sympathy for you, then I expect the same in return.”

Yet as Shinzaburō ended his frustrated outpouring, he saw that Tsuyuko and Yoneko wore expressions of total indifference. As he sat there unnerved by this transformation, Yoneko said with insouciance, “Well, men are the stronger sex. You are the blessed ones. Everything will turn out right for you in the end, I’m sure. I don’t have the least concern about you. What worries me is Miss Tsuyuko. Women are so utterly powerless. Can Miss Tsuyuko really go through her life as a single woman, I ask myself. Can she endure this way? Hmm, what’s that? The same goes for me, you’re thinking? Oh, you really need not worry about me. Please concern yourself solely with Miss Tsuyuko. And just to be clear, I’m not ordering you to commit lovers’ suicide. We have no wish to place that kind of burden on your shoulders. What we would like is for you to purchase our product.”

Shinzaburō had not been conscious of any ongoing preparations, but now, with timing that seemed almost too impeccable, Tsuyuko set something down on the table with a thump.

It was some kind of lantern thing. Didn’t those have some special name?

“It’s a tōrō, Mr. Hagiwara,” said Yoneko with a triumphant grin, as if she’d read his thoughts. These two were really too much to take.

“Of late, these portable lanterns are enjoying a surprising revival, Mr. Hagiwara! You’ll find they’re far more fashionable than flashlights! Many customers like to coordinate them with the design of their yukata when attending summer festivals, and now that it’s Obon, they’re great for hanging outside the house to welcome home the souls of the returning dead. Honestly, they are extremely popular! The exterior is silk crepe with a peony pattern and is very well-received by the ladies. Do you happen to be married Mr. Hagiwara? I believe you are, aren’t you?’

“Oh Shinzaburō!” exclaimed Tsuyuko in a high voice. “How absolutely despicable of you! What about me?”

“Oh Miss Tsuyuko, how cruel destiny can be! I tell you, she really does have the most awful luck with men. I go out of my mind with worry. Now, where was I? Oh yes, I was just saying that these peony tōrō lanterns are extremely popular with the ladies. Your wife will be absolutely delighted, I am sure. I have heard that those from the Western climes are good at surprising their lady friends with flowers and such little gestures of their affection, but males from Japan often neglect to do such things. Don’t get me wrong—I’m not trying to suggest that the same is true of you, Mr. Hagiwara! Only that with your unemployment causing your wife such hardship, occasionally gifting things that women like, these lanterns for example, is a rather good strategy, by which I mean to say—it wouldn’t do you any harm, would it?”

“Oh Shinzaburō! How it grieves me to think of you giving presents to another woman!”

“There there, Miss Tsuyuko. Do calm yourself. I’m quite sure that Shinzaburō will be buying two lanterns, one of which he will of course be presenting to you!”

“Oh Miss Yoneko, what are you saying! There is no way that a man as considerate as Shinzaburō would forget about you! He shall be buying three lanterns, for sure! Three, at the very least.”

So this is their sales strategy, thought Shinzaburō, utterly aghast. After watching them prattle on at each other for a while, he felt he’d had enough of being neglected.

“Look, I’m sorry, but I don’t want any of your lanterns. Contrary to what you seem to think, if I go around buying such stuff while I’m without an income, the only thanks I’ll get from my wife will be a good telling-off.”

There was a second’s pause and then a sickly, snakelike voice came slithering out of Tsuyuko’s mouth.

“Then we shall resent you, Shinzaburō.”

“W-What?”

“We will resent you,” she repeated, fixing him with a withering look.

“Now, now, Tsuyuko,” said Yoneko. “It will not do to rush Mr. Hagiwara into a decision. We mustn’t pressure him. Let’s allow him first to experience our much-vaunted lanterns. I have no doubt he’ll be delighted by them. Mr. Hagiwara, would you mind advising me where your light switch is?’

Shinzaburō looked toward the switch and, as if in silent understanding, the lights in the room immediately dimmed. Before Shinzaburō had time to register his surprise, the lantern on the table swelled with light, illuminating the darkened room.

On the other side floated the green-white faces of the two women. Shinzaburō remembered playing this kind of game with his friends at school—everyone shining flashlights under their faces to try and scare one other. Finally acclimatizing to the evening’s unrelenting stream of reason-defying events, Shinzaburō was sufficiently relaxed to reminiscence about his boyhood. Filtering through the peonies, the soft lantern light spilled into the room. It was as if another world had materialized, right there in his living room. With their legs concealed under the table, the women looked as if they consisted of their upper bodies alone, free-floating in the air.

“You two look just like gho—, I mean, you seem somehow not of this world.”

Immediately regretting his choice of words, Shinzaburō grimaced.

“You mean us?” asked Yoneko with a wry smile.

She seemed not at all displeased by the remark.

“And what would you do if we were . . . not of this world?” asked Tsuyuko, looking up at him through her eyelashes, lips iridescent with gloss, or spit, or something else entirely. Then without waiting for his answer, the two women dissolved into a fit of giggles.

The lights in the room blinked on.

“So you see, that’s how it works. It’s a rather good product, wouldn’t you say?” Yoneko and Tsuyuko smiled in unison.

“Indeed, but I really don’t need it,” said Shinzaburō. The two women shared a glance and nodded gravely. When they turned to look at Shinzaburō again, their faces bore entirely different expressions. “If you don’t buy our lanterns, Shinzaburō, I will perish,” said Tsuyuko.

“Now, Mr. Hagiwara, did you hear that? Miss Tsuyuko says she’s going to perish,” said Yoneko.

“Do what you like to me, I’m not going to leave here until Shinzaburō buys some!” said Tsuyuko, breaking into a screechy voice like a child throwing a tantrum.

“Oh, listen to that!” Yoneko went on persistently in a low murmur. “If your wife comes home and sees Tsuyuko here, she’ll be terribly jealous, won’t she, Mr. Hagiwara? If only you would buy a lantern, we’d leave immediately.” While Yoneko was speaking, she and Tsuyuko snuck glances at Shinzaburō.

“I said I wasn’t going to buy one,” said Shinzaburō firmly. The more excitable the two women grew, the more he found himself regaining his composure.

“Did you hear that, Miss Tsuyuko? You’d be better off giving up on a rotten-hearted man like this one.”

“No, Miss Yoneko. I trust him. I trust dear Shinzaburō.”

“Now, Mr. Hagiwara. Did you hear what Miss Tsuyuko just said? How awfully touching.”

Observing the farce being played out before his eyes, Shinzaburō found himself unexpectedly marveling at their teamwork. Yoneko was stunning in her supporting role. There was no way Tsuyuko alone would have garnered such impact. Their methods certainly ran against the grain of traditional sales techniques, but it had to be said there was something formidable about them. It must be down to desperation, Shinzaburō thought—desperation at their lack of success. He even began to consider just buying one of the damned things out of pity, but when he pictured his wife’s expression upon seeing the new acquisition, the temptation fizzled away. For two or three years now, his wife had only had eyes for Scandinavian homeware, not this traditional Japanese decor.

Tsuyuko and Yoneko were keeping up their noisy masquerade. With sudden clarity he saw that whether he chose to buy a lantern or not, hell awaited him regardless.

The next thing he knew, Shinzaburō was laughing out loud. It felt like a long time since he’d laughed properly like this. If push came to shove, he thought as he chuckled, you could carry on life like these goofballs did, and you’d still be fine. Well, depending on your definition of “fine,” of course—but at any rate, nothing terrible would happen to you if you broke the rules. With that thought, Shinzaburō felt a hot surge behind his eyes, and quickly clenched his teeth.

Apparently unnerved by this alteration in him, Yoneko and Tsuyuko spoke.

“Have you had a change of heart, Mr. Hagiwara?”

“Have you decided to accommodate my request, Shinzaburō?”

“No, I’m not going to buy a lantern. But, still, thank you, nonetheless.” His voice sounded dignified, somehow, and free. When he next looked, Tsuyuko and Yoneko appeared to be suspended in mid-air. The next moment, the lights in the room went out again, as if someone had blown out all the candles.

Shinzaburō woke to the sound of sparrows cheeping outside the window. He lifted his head from the living room floor and saw four lanterns strewn about him. Tsuyuko and Yoneko were nowhere to be seen.

At the sound of keys in the door, Shinzaburō quickly sat up and prepared himself for the next onslaught. But the person who came rushing into the room with a loud ‘Hi! I’m home!’ carrying her suitcase so the wheels didn’t leave marks on the floor was his wife. Taking in the messy room, with Shinzaburō stretched out sloppily on the floor, she frowned and said in a tone of utter disbelief, “Oh, for heaven’s sake!” Shinzaburō couldn’t help but notice that her gestures and her expressions weren’t unlike those of Tsuyuko and Yoneko. Why did all women pull the same face when they looked at him?

“What have you been doing in here? I thought you were supposed to be looking for a job while I was gone! And what on earth are these? Some kind of failed DIY experiment?”

Listening to his wife’s protestations as she picked up the lanterns littering the room, Shinzaburō thought of his wallet, which would probably be a few notes lighter, and a pang of dread spread through him. Of course, for a salesperson to take money without permission went against every rule in the book, but he wouldn’t have put it past those two. It was basically theft! How much were they charging for those blasted lanterns, anyway? Ah, there was nothing for it—now he really would have to find a job as soon as possible. Shinzaburō gingerly pulled himself up from the floor, from where a pool of light filtering through the curtain gently flickered.

Shinzaburō spotted Tsuyuko and Yoneko only once after that encounter.

He’d been on the early shift at his new workplace and was back home preparing dinner when he heard a woman’s voice outside the window. Peering through a gap in the curtain, he saw the two of them standing at the gate next to the nameplate. They appeared to be in serious conversation.

Shinzaburō remembered. It had slipped his mind entirely, but after coaxing the truth about the peony lanterns out of Shinzaburō, his wife had bought a sticker at the home goods store that read no sales visitors! and had stuck it up next to their nameplate. That had been about a year ago now. The business cards they had given him that evening many months ago had mysteriously vanished, and for some reason he couldn’t recall the name of their company, though he was sure he’d made a mental note of it.

“There’s one here too! How cruel.”

“We can’t go in now, not with this talisman stuck up . . . What a pity!”

“It’s so heartless.”

“It really is sheer heartlessness.”

Tsuyuko and Yoneko were wearing the same outfits as before.

A talisman, indeed! Shinzaburō smirked. Such melodrama, as usual! Just what exactly was the deal with these two? And yet, he couldn’t deny that he was a little bit pleased to have seen them again. The next moment, they both looked toward the window in unison and Shinzaburō lunged away from the curtain.